Does Local Anesthetic Temperature Affect the Onset and Duration of Ultrasound-Guided Infraclavicular Brachial Plexus Nerve Block

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nerve Blocks for Surgery on the Shoulder, Arm Or Hand

Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand Information for patients and families First Edition 2015 www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand This leaflet is for anyone who is thinking about having a nerve block for an operation on the shoulder, arm or hand. It will be of particular interest to people who would prefer not to have a general anaesthetic. The leaflet has been written with the help of patients who have had a nerve block for their operation. Throughout this leaflet we have used the above symbol to highlight key facts. Brachial plexus block? The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. It contains all the nerves that supply movement and feeling to your arm – from your shoulder to your fingertips. A brachial plexus block is an injection of local anaesthetic around the brachial plexus. It ‘blocks’ information travelling along these nerves. It is a type of nerve block. Your arm becomes numb and immobile. You can then have your operation without feeling anything. The block can also provide excellent pain relief for between three and 24 hours, depending on what kind of local anaesthetic is used. A brachial plexus block rarely affects the rest of the body so it is particularly advantageous for patients who have medical conditions which put them at a higher risk for a general anaesthetic. A brachial plexus block may be combined with a general anaesthetic or with sedation. This means you have the advantage of the pain relief provided by a brachial plexus block, but you are also unconscious or sedated during the operation. -

Nerve Injury After Peripheral Nerve Block: Allbest Rights Practices Reserved

PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION AVAILABLE AT ANESTHESIOLOGYNEWS.COM Nerve Injury After Peripheral Nerve Block: AllBest rights Practices reserved. Reproduction and Medical-Legal in whole or in part without Protection permission isStrategies prohibited. Copyright © 2015 McMahon Publishing Group unless otherwise noted. DAVID HARDMAN, MD, MBA Professor of Anesthesiology Vice Chair for Professional Affairs Department of Anesthesiology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, North Carolina Dr. Hardman reports no relevant financial conflicts of interest. he risk for permanent or severe nerve injury after peripheral nerve blocks (PNBs) is Textremely low, irrespective of its etiology (ie, related to anesthesia, surgery or the patient). The risk inherent in a procedure should always be explicitly discussed with the patient (sidebar, page 4). In fact, it may be better to define this phenomenon ultrasound-guided axillary blocks were used, demon- as postoperative neurologic symptoms (PONS) or peri- strated a very low nerve injury rate of 0.0037% at hos- operative nerve injuries (PNI) in order to help stan- pital discharge.1-7 dardize terminology. Permanent injury rates, as defined A 2009 prospective case series involving more than by a neurologic abnormality present at or beyond 12 7,000 PNBs, conducted in Australia and New Zealand, months after the procedure, have consistently ranged demonstrated that when a postoperative neurologic from 0.029% to 0.2%, although the results of a recent symptom was diagnosed, it was 9 times more likely to multicenter Web-based survey in France, in which be due to a non–anesthesia-related cause than a nerve ANESTHESIOLOGY NEWS • JULY 2015 1 block–related cause.6 On the other hand, it is well doc- PNI rate of 1.7% in patients who received a single-injec- umented in the orthopedic and anesthesia literature tion interscalene block (ISB). -

Nerve Blocks for Surgery on the Shoulder, Arm Or Hand

The Association of Regional The Royal College of Anaesthetists of Great Anaesthesia – Anaesthetists Britain and Ireland United Kingdom Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand Information for patients and families www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo First edition 2015 This leaflet is for anyone who is thinking about having a nerve block for an operation on the shoulder, arm or hand. It will be of particular interest to people who would prefer not to have a general anaesthetic. The leaflet has been written with the help of patients who have had a nerve block for their operation. You can find more information leaflets on the website www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo. The leaflets may also be available from the anaesthetic department or pre-assessment clinic in your hospital. The website includes the following: ■ Anaesthesia explained (a more detailed booklet). ■ You and your anaesthetic (a shorter summary). ■ Your spinal anaesthetic. ■ Anaesthetic choices for hip or knee replacement. ■ Epidural pain relief after surgery. ■ Local anaesthesia for your eye operation. ■ Your child’s general anaesthetic. ■ Your anaesthetic for major surgery with planned high dependency care afterwards. ■ Your anaesthetic for a broken hip. Risks associated with your anaesthetic This is a collection of 14 articles about specific risks associated with having an anaesthetic or an anaesthetic procedure. It supplements the patient information leaflets listed above and is available on the website: www.rcoa.ac.uk/patients-and-relatives/risks. Throughout this leaflet and others in the series, we have used this symbol to highlight key facts. 2 NERVE BLOCKS FOR SURGERY ON THE SHOULDER, ARM OR HAND Brachial plexus block? The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. -

OHSU Regional Anesthesia Peripheral Nerve Block Overview

OHSU Regional Anesthesia Peripheral Nerve Block Overview Recommended information: To view 3 short informative videos about nerve blocks, how they are placed, and postoperative care, please search for OHSU Home Pump in your internet browser, or visit: http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/health/services/anesthesiology/for-patients/home-pump.cfm What does an anesthesiologist do? An anesthesiologist is a medical doctor who keeps you safe and comfortable during surgery. An anesthesiologist will meet with you prior to surgery to make sure you are prepared and medically fit to undergo surgery and anesthesia. Your anesthesiologist will discuss a plan for what kind of anesthesia you will receive. During the surgery, your anesthesiologist will monitor and regulate your critical life functions, such as your heart rate, blood pressure, and level of oxygen in the blood. And, they take care of you after surgery to make sure you’re as comfortable as possible as you recover. What are the types of anesthesia? 1. General anesthesia. This type of anesthesia is given as an anesthetic gas you breathe in, or as an intravenous medication given through an intravenous catheter (IV). It makes you lose consciousness. While the anesthesia is working, many of your body’s functions will slow down or need help to work effectively. A tube may be placed in your throat to help you breathe. Once your surgery is complete, your anesthesiologist will reverse the medication and be with you as you regain consciousness. It is used for major operations. 2. Monitored anesthesia care or IV sedation. IV sedation causes you to feel relaxed and can result in various levels of consciousness. -

Universal Documentation Sheet for Peripheral Nerve Blocks

THE JOURNAL OF NEW YORK SCHOOL May 2009 V o l u m e OF REGIONAL ANESTHESIA 12 UNIVERSAL DOCUMENTATION SHEET FOR PERIPHERAL NERVE BLOCKS BY KISHOR GANDHI MD MPH, VIJAY PATEL MD, THOMAS MALIAKAL MD, DAQUAN XU MD, KAMIL FLISINSKI BS Author Affiliation: Department of Anesthesiology, St. Luke’s and Roosevelt Hospitals, New York, NY Reimbursements for peripheral nerve blocks (PNB’s) can be complicated by charge bundles that utilize specific procedure codes (CPT) and unit values.1-2 Individual providers use specific information contained in the patient’s medical records for reimbursement. Careful documentation for PNB’s should include: Surgical diagnosis, name of surgeon requesting regional service, and details of procedure (specific nerve block, reason of nerve block, type of needle and catheter used, ultrasound guided versus neurostimulation technique, and the local anesthetic used). In addition, attaching a printed photograph of the nerve block procedure (containing patient identification and localization of the nerve) will also aid in reimbursements from insurance providers. We at NYSORA have found huge discrepancies in billed amount for PNB’s compared to what is reimbursed by different providers.3 We have developed a universal billing sheet for institution to aid in reimbursements. The Journal of NYSORA 2009; 12: 23-24 REFERENCES 1. Mariano, ER. Billing for Peripheral Nerve Blocks (United States). Available at: http://edmariano.com/billing-for- regional-anesthesia 2. Gerancher JC, Viscusi ER, Liguori Ga, McCartney CI, Williams BA, Ilfeld BM, Grant SA, Hebl JR, Hadzic A. Development of a standardized peripheral nerve block procedure note form. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. -

Fascia Iliaca Block in the Emergency Department

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine Best Practice Guideline Fascia Iliaca Block in the Emergency Department 1 Revised: July 2020 Contents Summary of recommendations ...................................................................................................... 3 Scope ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Reason for development ................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Considerations ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Safety of FIB ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Improving safety of FIB .................................................................................................................. 5 Controversies regarding FIB ......................................................................................................... 5 Efficacy of FIB ................................................................................................................................... 6 Procedures within ED .................................................................................................................... -

Interscalene Brachial Plexus Nerve Block

FAQs Interscalene Brachial Plexus Nerve Block Frequently asked questions Find information on the efficacy and safety of EXPAREL in interscalene brachial plexus nerve block, as well as guidance on administration. What is EXPAREL? What is the indication for EXPAREL in nerve block? What was the study design of the pivotal trial of EXPAREL for interscalene brachial plexus nerve block? What were the efficacy results for the pivotal study of EXPAREL for interscalene brachial plexus nerve block? What was the impact of EXPAREL on opioid use in the interscalene brachial plexus nerve block study? Were any patients opioid free in the pivotal study of EXPAREL for interscalene brachial plexus nerve block? What were the safety results for EXPAREL in the pivotal interscalene brachial plexus nerve block study? Was there any phrenic nerve involvement noted in the interscalene brachial plexus nerve block trial? Were symptoms of Horner’s Syndrome noted in the interscalene brachial plexus nerve block trial? What is the incidence of paresthesia seen in the interscalene brachial plexus nerve block trial of EXPAREL? What was the onset of action of EXPAREL in the interscalene brachial plexus nerve block trial? 1 Please see Important Safety Information on page 14 and full Prescribing Information. BIOSCIENCES, INC. FAQs Frequently asked questions continued How long did sensory blockade and motor blockade last with EXPAREL in interscalene brachial plexus nerve block? Is the plasma concentration of bupivacaine directly related to pain relief or motor function? How -

Fascia Iliaca Compartment Blocks: Different Techniques and Review of the Literature

Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 33 (2019) 57e66 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bean 5 Fascia iliaca compartment blocks: Different techniques and review of the literature * Matthias Desmet, MD, PhD, Consultant Anaesthesist a, , Angela Lucia Balocco, MD, Nysora Research fellow b, Vincent Van Belleghem, MD, Consultant Anaesthesist a a Dept of Anesthesia, AZ Groeninge Hospital, Pres. Kennedylaan 4, 8500 Kortrijk, Belgium b Department of Anaesthesiology, Ziekenhuizen Oost Limburg (ZOL), Schiepse Bos 6, 3600 Genk, Belgium Keywords: The fascia iliaca compartment block has been promoted as a fascia iliaca compartment block valuable regional anesthesia and analgesia technique for lower anatomy hip fracture limb surgery. Numerous studies have been performed, but the fi total hip arthroplasty evidence on the true bene ts of the fascia iliaca compartment supra-inguinal fascia iliaca compartment block is still limited. Recent anatomical, radiological, and clinical block research has demonstrated the limitations of the landmark infrainguinal technique. Nevertheless, this technique is still valu- able in situations where ultrasound cannot be used because of lack of equipment or training. With the introduction of ultrasound, a new suprainguinal approach of the fascia iliaca has been described. Research has demonstrated that this technique leads to a more reliable block of the target nerves than the infrainguinal tech- niques. However, more research is needed to determine the place of this technique in clinical practice. © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Anatomy of the lumbar plexus and implications for regional anesthesia The lumbar plexus consists of the ventral rami of the L1-L4 spinal nerves and commonly a small contribution of the subcostal nerve from T12. -

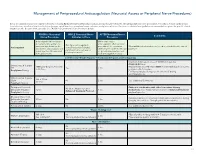

Neuraxial Access Or Peripheral Nerve Procedures)

Management of Periprocedural Anticoagulation (Neuraxial Access or Peripheral Nerve Procedures) Below are guidelines to prevent spinal hematoma following Epidural/Intrathecal/Spinal procedures and perineural hematoma following peripheral nerve procedures. Procedures include epidural injec- tions/infusions, intrathecal injections/infusions/pumps, spinal injections, peripheral nerve catheters, and plexus infusions. Decisions to deviate from guideline recommendations given the specific clinical situation are the decision of the provider. See ‘Additional Comments’ section for more details. PRIOR to Neuraxial/ WHILE Neuraxial/Nerve AFTER Neuraxial/Nerve Comments Nerve Procedure Catheter in Place Procedure How long should I hold prior When can I restart to neuraxial procedure? (i.e. anticoagulants after neuraxial Can I give anticoagulants minimum time between the procedures? (i.e. minimum What additional information do I need to consider for the care of Anticoagulant concurrently with neuraxial, last dose of anticoagulant and time between catheter removal patients? peripheral nerve catheter, or spinal injection OR neuraxial/ or spinal/nerve injection and plexus placement? nerve placement) next anticoagulation dose) Low-Molecular Weight Heparin, Unfractionated Heparin, and Fondaparinux Maximum total heparin dose of 10,000 units per day (5000 SQ Q12 hrs) Unfractionated Heparin 5000 units Q 12 hrs – no time Heparin 5000 units SQ 8 hrs is NOT recommended with concurrent SQ Yes 2 hrs restrictions neuraxial catheter in place Prophylaxis Dosing For IV prophylactic dosing, use ‘treatment’ IV dosing recommendations. Unfractionated Heparin SQ: 8-10 hrs SQ/IV No 2 hrs See ‘Additional Comments’ IV: 4 hrs Treatment Dosing Enoxaparin (Lovenox), Caution in combination with other hemostasis-altering No (Note: May be used for Dalteparin (Fragmin) 12 hrs 4 hrs medications. -

PATIENT EDUCATION Axillary

EISENHOWER HEALTH This illustration represents Peripheral possible peripheral nerve block Interscalene locations Intercostal Supraclavicular (Back or Side) Nerve Block PATIENT EDUCATION Axillary Transversus PERIPHERAL NERVE BLOCKS Abdominis Plane (TAP)* A peripheral nerve block has been requested by your surgeon for improved pain control after surgery. It is a Quadratus type of regional anesthesia that involves an injection of Lumborum* numbing medicine (local anesthetic) around the nerves Femoral to reduce transmission of pain signals to the brain to Fascia Adductor Canal Iliaca keep you comfortable and control your pain. A peripheral nerve block does not put you to sleep. Sciatic However, you will likely receive IV sedation to relax you prior to the start of your nerve block. The type of Popliteal peripheral nerve block you will receive depends on the Saphenous type of surgery. Peripheral nerve blocks are performed *These blocks are performed on both sides (bilateral) whereas the by a board certified anesthesiologist under ultrasound other blocks may only be performed on side of surgery. guidance often with electric stimulation. Risks and Possible Complications of a Peripheral The reverse side of this document lists the most common Nerve Block: types of nerve blocks based on the type of surgery. Peripheral nerve blocks are very safe and rarely cause Site of the injection depends on the part of the body significant side effects or complications. However, risks being treated. A peripheral nerve block can partially can include: or completely block sensation in an arm, leg or other • Infection • Seizures (very rare) area for surgery but doesn’t put you to sleep. -

Regional Anesthesia Resident Handbook

REGIONAL ANESTHESIA RESIDENT HANDBOOK Stanford University Department of Anesthesia 2017-2018 Special thanks to previous fellows and attendings who have contributed to this handbook: Rachel Outterson, MD, Gunjan Kumar, MD, Nisha Malhotra, MD, Jenna Hansen, MD, Omar Malik, MD, Jack Kan, MD, Nate Ponstein, MD, Brett Miller, MD, Vanila Singh, MD Page 1 of 18 Table of Contents I. Preparing for Blocks a. The Night Before b. The Morning Of c. Documentation and Orders i. Ultrasound image ii. EPIC Notes iii. EPIC orders iv. Block followup note v. Call schedule II. Other Helpful Information a. OSC/SMOC b. Journal Club III. Consenting Patients – Risks and Benefits IV. Reference: a. Upper Extremity Blocks b. Lower Extremity Blocks c. Paravertebral Blocks d. TAP Blocks e. Anticoagulation Guidelines Page 2 of 18 I. Preparing for Blocks a. The Night Before • Look over the emailed schedule from the fellow for the plan for both Stanford and OSC. • When pre-oping the patients: pay particular attention to any chronic pain conditions, allergies, anticoagulation, Hct/Coags, and cardio-pulmonary comorbidities, including anything that might delay or cancel surgery. • You do not need to call your attending for the plan at Stanford or OSC, though they will be happy to answer questions if it helps you to prepare better. st • If several 1 case blocks, please call/consent your assigned patient the day prior and remind patients to be at registration at 5AM Tuesday thru Friday (6AM on Mondays). b. The Morning Of • Arrival time for residents is usually between 5:30 and 6:00, depending on how many first case blocks. -

Anesthetic Agents of Plant Origin: a Review of Phytochemicals with Anesthetic Activity

molecules Review Anesthetic Agents of Plant Origin: A Review of Phytochemicals with Anesthetic Activity Hironori Tsuchiya Department of Dental Basic Education, Asahi University School of Dentistry, 1851 Hozumi, Mizuho, Gifu 501-0296, Japan; [email protected]; Tel.: +81-58-329-1266 Received: 13 June 2017; Accepted: 17 August 2017; Published: 18 August 2017 Abstract: The majority of currently used anesthetic agents are derived from or associated with natural products, especially plants, as evidenced by cocaine that was isolated from coca (Erythroxylum coca, Erythroxylaceae) and became a prototype of modern local anesthetics and by thymol and eugenol contained in thyme (Thymus vulgaris, Lamiaceae) and clove (Syzygium aromaticum, Myrtaceae), respectively, both of which are structurally and mechanistically similar to intravenous phenolic anesthetics. This paper reviews different classes of phytochemicals with the anesthetic activity and their characteristic molecular structures that could be lead compounds for anesthetics and anesthesia-related drugs. Phytochemicals in research papers published between 1996 and 2016 were retrieved from the point of view of well-known modes of anesthetic action, that is, the mechanistic interactions with Na+ channels, γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and lipid membranes. The searched phytochemicals include terpenoids, alkaloids and flavonoids because they have been frequently reported to possess local anesthetic, general anesthetic, antinociceptive, analgesic or sedative property. Clinical applicability of phytochemicals to local and general anesthesia is discussed by referring to animal in vivo experiments and human pre-clinical trials. This review will give structural suggestions for novel anesthetic agents of plant origin. Keywords: phytochemical; local anesthetic; general anesthetic; plant origin; pharmacological mechanism; lead compound 1.