Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Policy 10.3.12

UNIVERSITY POLICY Policy Student Policy Prohibiting Sexual Harassment, Sexual Violence, Relationship Violence, Name: Stalking, and Related Misconduct Academic: Student Services Formerly Section #: 10.3.12 Section Title: & Other Student-Related N/A Book: Policies and Programs Approval Board of Governors Adopted: 10/14/2015 Reviewed: 12/17/2019 Authority: Responsible Senior Vice President for Revised: 12/17/2019 Executive: Academic Affairs Office of Enterprise Risk Management, Ethics and Compliance Responsible 973-972-8093 Academic Affairs Contact: Office: 800-215-9664 http://erm.rutgers.edu/departments/complia nce_hotline.html 1. Policy Statement Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is committed to fostering an environment that is safe and secure and free from sexual and gender-based discrimination and harassment, sexual violence, dating and domestic violence, stalking and other related misconduct. The University recognizes its responsibility to increase awareness of such misconduct, prevent its occurrence, support victims, deal fairly and firmly with offenders, and diligently investigate reports of misconduct. In addressing these issues, all members of the University must come together to respect and care for one another in a manner consistent with our deeply held academic and community values. This Policy sets forth how the University defines and addresses sexual and gender-based harassment, sexual violence, stalking and relationship violence and related misconduct involving University students. 2. Reason for Policy The University is required to comply with Title IX of the Higher Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs and activities. Similarly, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (VAWA) requires prompt, fair and impartial investigation and resolution of allegations of sexual assault, stalking, dating violence, and domestic violence. -

Alumni Weekend Alumni Weekend

32. Individual Reunion Dinners for Classes n 1949 $50 per person $50 x #______ = $__________ Rutgers University Alumni Association n 1954 $50 per person $50 x #______ = $__________ n 1959 $65 per person $65 x #______ = $__________ n 1964 $75 per person $75 x #______ = $__________ YOU’RE INVITED n 33. Scarlet Night at the audi Rutgers Club Alumni (1969 – 2009 and various groups) $65 per person $65 x #______ = $__________ Indicate class or group affiliation: ___________________________________ ____________ n 34. after-Hours Bar Hop #______ FREE Alumni WEEKEnD Sunday May 18 Rutgers University–New Brunswick n 35. University Commencement Exercises #______ FREE WEEKEnD Spring is here, and there are many exciting new advancements happening ON-CaMPUS HOUSING IN STONIER HaLL (College Avenue) Rutgers University–New Brunswick at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. New buildings dot the landscape, and Single Occupancy $65 per night Friday Night # of rooms ______ x $65 = $__________ ongoing construction brings the promise of a wealth of new opportunities for Saturday Night # of rooms ______ x $65 = $__________ future students. This year, come back to Rutgers and experience first-hand Double Occupancy $100 per night Friday Night # of rooms ______ x $100 = $__________ May 15-18, 2014 how it is growing to meet the needs of its students, residents of New Jersey, Saturday Night # of rooms ______ x $100 = $__________ and people around the world. Rutgers PRIDE GEaR Alumni Weekend is a time to celebrate your accomplishments as a student (all items pictured on Ralumni.com/NBweekend) and since graduation, reminisce with your friends and former roommates, Orders with memorabilia must be received by April 10. -

Your Guide to Living on Campus

RESIDENCE LIFE YOURYOUR GUIDEGUIDE TOTO LIVINGLIVING ONON CAMPUSCAMPUS COMING TO CAMPUS About Us Transition Rutgers University–New Brunswick Residence Coming to a new place, such as Rutgers University, Life creates a safe, welcoming, and inclusive can be an exciting transitional time. Residence environment where student learning, development, Life is here to support your college journey. Enjoy and individuality is championed and supported. the benefits of living with people who are sharing Residents are our first priority. the same experiences. Rest assured knowing that our trained, live-in residence life staff are always Rutgers University offers a variety of special available for assistance, advice, or just to talk. living options to provide a unique and rewarding on-campus living experience. These residential experiences create a strong sense of community and Rutgers pride based on similar interests and goals. The programs provide opportunities for students to connect and share experiences based on areas of similar academic, cultural, language, or thematic interests. Statistics 16,000+ Residential Students Rutgers is one of the largest residential communities in the nation. 50+ Residence Halls Halls range from single and double rooms, suites, and apartments. Residential Care and Student Support 29 Living-Learning and Thematic Communities and The residential care model consists of special 2 Residential Colleges housing accommodations for students with Explore new opportunities, discover your interests, disabilities and other medical needs, and support and connect with other students. for students facing a wide variety of challenges. We meet with students to assess their needs, connect 400+ On-Campus Staff students to helpful resources, and help to ensure a On-campus staff live within the halls to support safe and healthy living environment. -

Catalogue of the Officers and Alumni of Rutgers College

* o * ^^ •^^^^- ^^-9^- A <i " c ^ <^ - « O .^1 * "^ ^ "^ • Ellis'* -^^ "^ -vMW* ^ • * ^ ^^ > ->^ O^ ' o N o . .v^ .>^«fiv.. ^^^^^^^ _.^y^..^ ^^ -*v^^ ^'\°mf-\^^'\ \^° /\. l^^.-" ,-^^\ ^^: -ov- : ^^--^ .-^^^ \ -^ «7 ^^ =! ' -^^ "'T^s- ,**^ .'i^ %"'*-< ,*^ .0 : "SOL JUSTITI/E ET OCCIDENTEM ILLUSTRA." CATALOGUE ^^^^ OFFICERS AND ALUMNI RUTGEES COLLEGE (ORIGINALLY QUEEN'S COLLEGE) IlSr NEW BRUJSrSWICK, N. J., 1770 TO 1885. coup\\.to ax \R\l\nG> S-^ROUG upsoh. k.\a., C\.NSS OP \88\, UBR^P,\^H 0? THP. COLLtGit. TRENTON, N. J. John L. Murphy, Printer. 1885. w <cr <<«^ U]) ^-] ?i 4i6o?' ABBREVIATIONS L. S. Law School. M. Medical Department. M. C. Medical College. N. B. New Brunswick, N. J. Surgeons. P. and S. Physicians and America. R. C. A. Reformed Church in R. D. Reformed, Dutch. S.T.P. Professor of Sacred Theology. U. P. United Presbyterian. U. S. N. United States Navy. w. c. Without charge. NOTES. the decease of the person. 1. The asterisk (*) indicates indicates that the address has not been 2. The interrogation (?) verified. conferred by the College, which has 3. The list of Honorary Degrees omitted from usually appeared in this series of Catalogues, is has not been this edition, as the necessary correspondence this pamphlet. completed at the time set for the publication of COMPILER'S NOTICE. respecting every After diligent efforts to secure full information knowledge in many name in this Catalogue, the compiler finds his calls upon every one inter- cases still imperfect. He most earnestly correcting any errors, by ested, to aid in completing the record, and in the Librarian sending specific notice of the same, at an early day, to Catalogue may be as of the College, so that the next issue of the accurate as possible. -

Rutgers State University of New York

Academic Calendars Dates are subject to change. 2001–2002 2002–2003 September September 4 Tuesday Fall term begins. 3 Tuesday Fall term begins. November November 20 Tuesday Thursday classes meet. 26 Tuesday Thursday classes meet. 21 Wednesday Friday classes meet. 27 Wednesday Friday classes meet. 22 Thursday Thanksgiving recess begins. 28 Thursday Thanksgiving recess begins. 25 Sunday Thanksgiving recess ends. December December 1 Sunday Thanksgiving recess ends. 12 Wednesday Regular classes end. 11 Wednesday Regular classes end. 13 Thursday Reading period. 12 Thursday Reading period. 14 Friday Fall exams begin. 13 Friday Reading period. 21 Friday Fall exams end. 16 Monday Fall exams begin. 22 Saturday Winter recess begins. 23 Monday Fall exams end. January 24 Tuesday Winter recess begins. 21 Monday Winter recess ends. January 22 Tuesday Spring term begins. 20 Monday Winter recess ends. March 21 Tuesday Spring term begins. 17 Sunday Spring recess begins. March 24 Sunday Spring recess ends. 16 Sunday Spring recess begins. May 23 Sunday Spring recess ends. 6 Monday Regular classes end. May 7 Tuesday Reading period. 5 Monday Regular classes end. 8 Wednesday Reading period. 6 Tuesday Reading period. 9 Thursday Spring exams begin. 7 Wednesday Reading period. 15 Wednesday Spring exams end. 8 Thursday Spring exams begin. 23 Thursday University commencement. 14 Wednesday Spring exams end. 22 Thursday University commencement. IFC 1 12/6/01, 2:30 PM Mason Gross School of the Arts Graduate Catalog 2001--2003 Contents Academic Calendars inside front -

Admitted Student Life Brochure

STUDENT LIFE Find Your Truth. Define Your Path. At Rutgers University–New Brunswick, your future is wide open. Explore your interests with like-minded peers, or try out something completely new through our more than 750 student clubs and organizations ranging from sports and health, to cultures and languages, to arts and performance, to community service, and more. Explore museums and festivals both on and off campus, or take advantage of our many leadership programs to develop your skills and effectiveness. Opportunities abound for fieldwork in the furthest corners of the country and all around the world, and our proximity to New York City and Philadelphia will expand your cultural, entertainment, and career horizons. Dig In from Day One. From the moment you arrive, you’ll discover a world of exploration. Whether you’re looking to immerse yourself in the cultural landscape of New Brunswick, join a club, or try your hand in one of 100+ intramural teams or sports clubs, Rutgers offers something for everyone. SAMPLING OF CLUBS AND ACTIVITIES Accounting Association Kirkpatrick Choir American Sign Language Club Latino Student Council Asian Student Council Marching Band Bengali Students Association Mock Trial Association Big Buddy Model United Nations Team Black Student Union Muslim Student Association Catholic Student Association Orthodox Christian Campus Chemistry Society Ministries Circle K International Outdoors Club The Daily Targum Polish Club Debate Union Queer Student Alliance of Rutgers University Glee Club Scarlet Listeners Peer Counseling, Golden Key International Honor Crisis, and Referral Hotline 750+ Society student clubs and Sikh Student Association organizations Habitat for Humanity South Asian Performing Artists Hellenic Cultural Association TWESE, The Organization for African 100+ Hillel intramural teams and student- Students and Friends of Africa run sport clubs. -

On the Air Alumni Share Their Wrsu Memories

ALUMNI MAGAZINE 7YEARS0 ON THE AIR ALUMNI SHARE THEIR WRSU MEMORIES The magazine published by and for the Rutgers Alumni Association SPRING 2019 ALSO INSIDE: 150 YEARS OF COLLEGE FOOTBALL • LOYAL SONS AND DAUGHTERS • WHAT’S NEW ON CAMPUS 1766 is published by the Rutgers Alumni Association Vol. 36, No. 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Except for official announcements, the Rutgers Alumni Association disclaims all responsibility for opinions expressed and statements made in articles or advertisements published in this magazine. ANWAR HUSSAIN RC’89 EDITOR’S MESSAGE 188 Rutgers Alumni Association Dear Fellow Rutgers Alumni, YEARS IN EXISTENCE 188 YEARS OF SERVICE It is my honor to serve as the president of The Rutgers Alumni Association (RAA), the Greetings fellow Rutgers alumni, I hope you enjoy the reboot of 1766 Magazine! The Rutgers Alumni Association TO RUTGERS ALUMNI fourth oldest alumni association in the country. I was invited to participate in the RAA is the fourth oldest continuously After a recent hiatus, the publication is back and the team is over 15 years ago by a fellow alumnus as a way to stay connected with my alma mater, running organization in the looking forward to providing you with a glimpse of Rutgers and to give back to Rutgers. The RAA is a great organization where there are many United States. Building on Founded in 1831, the Rutgers Alumni Alumni Association events, updates on the great work that opportunities to volunteer and to stay connected with your alma mater and fellow Rutgers Revolutionary History, Association (RAA), a 501(c)(3) service Rutgers alumni are doing, and the latest happenings on alumni. -

Rutgers Free Speech Zones 11-12

Information For Prospective Students Current Students Faculty & Staff Alumni Parents Donors & Supporters This guide is intended to help the Rutgers community publicize Visitors events that they are sponsoring to audiences within the university. Information About Chalking Public Forums Publications Television The Campus Mailing Radio Web Academics Posting Tables Email Research Serving New Jersey Chalking on Campus Athletics Arts & Culture How can I chalk on campus? News & Media Rutgers affiliates are allowed to chalk on designated areas on Admissions campus, however they must be affiliated with a student organization Undergraduate or department, and must be chalking for that particular affiliation. Graduate Furthermore, prior approval is required and must occur at least one Continuing Education week before the date of the requested chalking. This can be done by completing a Chalking Request Form. Rutgers affiliates should Colleges & Schools complete a Chalking Request Form and submit it to: Undergraduate Graduate College Avenue Campus: Student Activities Center, Student Involvement Office (lower level) Jump To Rutgers Student Center, Room 449 Academic Affairs Academic Busch Campus: Departments Busch Campus Center, Student Involvement & Transitions Office, Administrative Affairs Room 121 Administrative Gateway Forms can be found at the Administrative Units http://getinvolved.rutgers.edu/organizations/resources-and- Catalogs training/forms-library . Centers & Institutes Computing Directions & Maps Faculties Mailing Global Programs Libraries How can I distribute information to student Online Giving mailboxes? Public Safety Schedule of Classes A campus post office is located on each campus in New Site Map Brunswick/Piscataway. Upon request, University Mail Services will University Human deliver both small (25 or fewer pieces) and mass mailings (25 or Resources more pieces) to individual student mailboxes. -

ON Campus Tours and Information Sessions Depart

WELCOME We are glad you decided to visit Rutgers University–New Brunswick! TRANSPORTATION We hope this travel guide has all Getting to Campus 2 the information you need for a Rutgers Visitor Center 4 successful trip! If you still need Navigating Campus 6 assistance please contact us at DINING 848-445-1000. Restaurant Listings 8 ACCOMMODATIONS Hotel Listings 16 SHOPPING Rutgers Gear 19 Grocery Stores/Pharmacies 20 Shopping Malls 20 ACTIVITIES Entertainment 21 1 TRANSPORTATION GETTING TO CAMPUS RUTGERS VISITOR CENTER NAVIGATING CAMPUS TRANSPORTATION GETTING TO CAMPUS Newark Liberty International Airport LaGuardia Airport John F. Kennedy International Airport PLANE SHUTTLE SERVICE Philadelphia International Airport TRAIN CAR SERVICE TAXI BY PLANE Rutgers–New Brunswick is located 41 miles from New York City and 66 miles from Philadelphia. There are four airports within 75 miles of the university. Newark Liberty International Airport is the closest geographically and will provide the easiest access to campus. From other airports, you should expect to travel through high traffic areas with tolls. NEWARK LIBERTY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - Newark, NJ 25.7 miles from Rutgers–New Brunswick Travel to Rutgers via: Automobile, Shuttle Service, Car Service, Taxi, NJ Transit Train AirTrain terminal within the airport *Recommended airport LAGUARDIA AIRPORT - New York, NY (Queens) 48.4 miles from Rutgers–New Brunswick Travel to Rutgers campus via: Automobile, Car Service, NJ Transit Train JOHN F. KENNEDY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - New York, NY (Queens) 50.1 miles from Rutgers–New Brunswick Travel to Rutgers campus via: Automobile, Car Service, NJ Transit Train PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - Philadelphia, PA 74.7 miles from Rutgers–New Brunswick Travel to Rutgers campus via: Automobile, Car Service 2 BY TRAIN NJ TRANSIT TRANSPORTATION New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor line provides New Brunswick with both local and express service between New York Penn Station, and Newark and Trenton, New Jersey. -

THE DAILY MEDIUM 126 College Ave., Suite 439, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 84TH EDITORIAL BOARD AMY DIMARIA

Volume 42, Number 22 WEDNESDAY APRIL 4, 2012 SERVINGTHE THE D RUTGERSAILY COMMUNITY MEDIUM SINCE 1970 Today: A Tad Breezy BARKING UP THE RIGHT TREE High: 40 Low: 69 Will the University be creating a dog racing team? Find out in today’s sports section! U. Officials Reconsider Stance on Yearly Festival BY AMY DIMARIA ing. EDITOR - IN - CHIEF “I think it really shows the Governors are open to student’s concerns,” said Clarke, a Despite cancelling Rutgersfest after a di- senior political science major. “Of course, a sastrous outing last year, the University’s lot of the responsibility will fall to the stu- Board of Governors has been meeting to dents as well to prove that this is an event discuss the possibility of reintroducing the worth having. I’m really interested to see event. what could happen with a second chance Following an open session meeting last like this.” night, Gerald Harvey, Vice Chair of the President Richard McCormick briefly Board said, “Rutgersfest has never been re- weighed in on the issue last night. moved from the table entirely. At this point “Cancelling Rutgersfest was not an easy it’s still just an idea for consideration.” decision for me. I put in a lot of consider- While still tentative, Harvey stated that ation and sought numerous opinions in the Rutgers could potentially hold the event as wake of the terrible events that occurred on early as the spring of the 2014-2015 school campus after the concert. The decision was BEN COOKS / ASSISTANT PHOTOGRAPHER year. made in haste and we should be open to Construction continues on the Livingston Apartments complex originally scheduled to Student representative to the Board, Kris- hearing personally from students who have ten Clarke was very encouraged by the meet- open in September of next year, but construction delays may push the occupancy to SEE RUTGERSFEST ON PAGE 7 mid-October. -

COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS: SELF-GUIDED TOUR X V L F Kreeger Rutgers University–Newk Brunswick: College Avenue Campus N

R D R C G H D W H O U E S OO W B N N G SN D O L I T D T R LA L SO I U D K LUDLOW ST I E W D E DR T U R M R E OW S N E R B BRI G H R D RESURRECTION E CT U E R E S L T T D R S DRI R T N L E O BURIAL PARK I A G S D IA P C R D R G S E R F O ROOSEVELT ST K T E L N LL R A O T N C DR ON A L N M V D ORCHARD ST E S S ILTON P E K E T I ST A ROOSEVELT ST MO R TA AV EN CT D N E RE T L V N CT RG S D A VE C R N MORRIS AVE E H T U BUENA VIS LA L E S NB H S C U U HIG T T S E A TO R L N F E S IE L L G E D N V N A E D 110 Ethel Road West RK AV R A PA HANSON LN E S GATES AVE E 609 S E O DEB HO V L A LD M C O Y N Y O FISHER AVE A R M E L R RAH D DR R O L S E I R R K B T O T CT R R U I C Y G N CT F D S I A L A A LN B R M W T R E R A To Rt 287 R A H M E F SHCRA G D T A N D I B S K R E L U L V H C D A A A O LL M U T E PS B I R O H H H ZIRKEL AVE P D C H IT E IR S L OE M E C A C O TA AV T S U H R S D R H L A A E NW Softball V OR BUENA VIS UBHC Children’s EB D Complex SON A D R T Transitional Residence N O 58D D Gordon Road HA O R University HOES LN M Gruninger W Office Building/ L AV R D ID OR E AN S Behavioral S Baseball Complex D Center for Applied 110 Ethel Road West Nichols O R SMOC N RIS LL Psychology Health Care Apartments R L IELD AVE P D Yellow Lot FE E T —North Busch Lab Center LN DU A H N RAC K 609 T WESTF K P B E H Johnson Fire & AR PL Environmental A T 58C B Apartments V ROC HE Emergency Services 62 E University Richardson 58C A RESA C P Services Building Behavioral Apartments Davidson Bainton Field S P T CT U Health Care Residence F T TO Motor Halls -

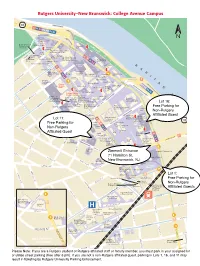

Rutgers University–New Brunswick: College Avenue Campus T

R D R C G H D W H O U E S O W N N S O O B L I G T D T D R N LA L S I U D K R L I E O W D R E D T U N R B M RB GE O U H S E RID E R E W D T RESURRECTION C U R E S S L T T T D R S D L R LT T N L E O E O BURIAL PARK I A G R S EV D IA W P S C R D I O G S R F O O K E R T R E L L A S T O T N N L S L C D T O A R LT N M R E V E D V O N E I E K S S S L O R S A VE O T I T A R C M T T R A O N C N T H O VE E D L IS A N RE V E A IS G T A AV N R ER S N D R OR P V C R E N E H T U U A D C M L B B L E C S N H T S U U IG S T T S H E A T T O R L N F E S IE L L G E D N V N A E D 110 Ethel Road West RK AV R A PA N SO VE AN N S A H L TE E E S GA E 609 S V E O D A HO V L E ER A D M C B SH L FI O Y N Y O A R M E L R T R R DR C O L S E A I R R K B T O T R R H U D I C A Y G N F S I A A L L D A N T B R C M W R R E R T A T C R A H M o H E F S G R D T A N D I B S t K R U L E 2 C L V 8 H D O A AM U A LL 7 T P I R O E S B H H H Z P D C H IT E IR IR S L O K M V E E C A A C L O E TA T A S U IS VE H S R V D R A N H L A A UE E R N Softball V B UBHC Children’s A O D B N E W Complex SO D R T Transitional Residence N O 58D D Gordon Road A O R H M W Office Building/ University HOES LN Gruninger L AV R D ID O E A Behavioral S D Center for Applied E O R Baseball Complex L R 110 Ethel Road West V S N Nichols R A N L Psychology D M Health Care I E L L S Apartments R S IE P D Yellow Lot F E F O T —North Busch Lab Center D L A T U N H ES C N RAC K 609 T K P B C E W H A Johnson R O P Fire & Environmental T 58C A R L B Apartments V H University Richardson Emergency Services 62 E E