Thesis, Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

The Big Draw International Festival: Drawn to Life Saturday, October 5, 2019

PRESS RELEASE The Walt Disney Family Museum Celebrates The Big Draw International Festival: Drawn to Life Saturday, October 5, 2019 San Francisco, October 1, 2019—The Walt Disney Family Museum is delighted to once again host The Big Draw, the world’s largest drawing festival. This annual, museum-wide community event will take place on OctoBer 5 and celeBrates Walt Disney’s contriButions to visual arts. In connection with this year’s “Drawn to Life” theme, experience special drawing sessions exploring nature- inspired art, create a care card for someone who needs a smile, learn how to draw Mickey Mouse, and more. Don’t miss film screenings of Disneynature’s Chimpanzee (2012) and Disney-Pixar’s Inside Out (2015), then connect back to stories told in our main galleries and in our special exhiBition, Mickey Mouse: From Walt to the World. This year, we are proud to partner with The Jane Goodall Institute’s Roots and Shoots. Founded by Goodall in 1991, Roots and Shoots is a youth service program for young people of all ages, whose mission is to foster respect and compassion for all living things, to promote understanding of all cultures and Beliefs, and to inspire each individual to take action to make the world a Better place for people, other animals, and the environment. In partnership with Caltrain and SamTrans, The Walt Disney Family Museum is pleased to offer free general admission to riders and employees, upon showing their Caltrain/SamTrans ticket or employee ID to the museum’s Ticket Desk. Riders and employees will also receive 15% off in the Museum Store. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

A Father's Love

A FATHER’S LOVE The documentary movie The March of the Penguins follows the Emperor Penguins of Antarctica on their incredible journey through ice and snow to mating grounds up to 70 miles inland. Narrated by Morgan Freeman, this beautiful film captures the drama of these three-foot-high birds in the most inhospitable of environments. Once the penguins have made the trek to their mating grounds and the females have produced their single eggs, a remarkable exchange occurs. Through an intricate dance, each mother swaps her egg into the father's care. At this point the father becomes responsible for the egg and must keep it warm. As this part of the story unfolds, the camera shows remarkable shots of the penguin fathers securing the eggs on top of their feet and sheltering them against the cold, which will drop to as low as 80 degrees below zero. Freeman narrates: Now begins one of nature's most incredible and endearing role reversals. It is the penguin male who will tend the couple's single egg. While the mother feeds and gathers food to bring back for the newborn, it is the father who will shield the egg from the violent winds and cold. He will make a nest for the egg atop his own claws, keeping it safe and warm beneath a flap of skin on his belly. And he will do this for more than two months… As the winter progresses, the father will be severely tested. By the time their vigil on top of the egg is over, the penguin fathers will have gone without food of any kind for 125 days, and they will have endured one the most violent and deadly winters on earth, all for the chick. -

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit SK Films: Facebook/Instagram/Youtube: Amber Hawtin @AmazonAdventureFilm Director, Sales & Marketing Twitter: @SKFilms Phone: 416.367.0440 ext. 3033 Cell: 416.930.5524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amazonadventurefilm.com 1 National Press Release: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMAZON ADVENTURE 3D BRINGS AN EPIC AND INSPIRATIONAL STORY SET IN THE HEART OF THE AMAZON RAINFOREST TO IMAX® SCREENS WITH ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY ON APRIL 18th. April 2017 -- SK Films, an award-winning producer and distributor of natural history entertainment, and HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, the acclaimed film production unit of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, announced today the IMAX/Giant Screen film AMAZON ADVENTURE will launch on April 18, 2017 at the World Premiere event at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The film traces the extraordinary journey of naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates - the most influential scientist you’ve never heard of – who provided “the beautiful proof” to Charles Darwin for his then controversial theory of natural selection, the scientific explanation for the development of life on Earth. As a young man, Bates risked his life for science during his 11-year expedition into the Amazon rainforest. AMAZON ADVENTURE is a compelling detective story of peril, perseverance and, ultimately, success, drawing audiences into the fascinating world of animal mimicry, the astonishing phenomenon where one animal adopts the look of another, gaining an advantage to survive. "The Giant Screen is the ideal format to take audiences to places that they might not normally go and to see amazing creatures they might not normally see,” said Executive Producer Jonathan Barker, CEO of SK Films. -

Donor-Advised Fund

WELCOME. The New York Community Trust brings together individuals, families, foundations, and businesses to support nonprofits that make a difference. Whether we’re celebrating our commitment to LGBTQ New Yorkers—as this cover does—or working to find promising solutions to complex problems, we are a critical part of our community’s philanthropic response. 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 1 A WORD FROM OUR DONORS Why The Trust? In 2018, we asked our donors, why us? Here’s what they said. SIMPLICITY & FAMILY, FRIENDS FLEXIBILITY & COMMUNITY ______________________ ______________________ I value my ability to I chose The Trust use appreciated equities because I wanted to ‘to‘ fund gifts to many ‘support‘ my community— different charities.” New York City. My ______________________ parents set an example of supporting charity My accountant and teaching me to save, suggested The Trust which led me to having ‘because‘ of its excellent appreciated stock, which tools for administering I used to start my donor- donations. Although advised fund.” my interest was ______________________ driven by practical considerations, The need to fulfill the I eventually realized what charitable goals of a dear an important role it plays ‘friend‘ at the end of his life in the City.” sent me to The Trust. It was a great decision.” ______________________ ______________________ The Trust simplified our charitable giving.” Philanthropy is a ‘‘ family tradition and ______________________ ‘priority.‘ My parents communicated to us the A donor-advised fund imperative, reward, and at The Trust was the pleasure in it.” ‘ideal‘ solution for me and my family.” ______________________ I wanted to give back, so I opened a ‘fund‘ in memory of my grandmother and great-grandmother.” 2 NYCOMMUNITYTRUST. -

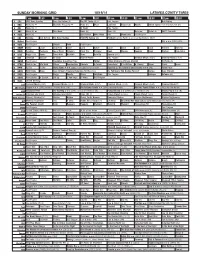

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

Epic Antarctica (Ng Endurance)

EPIC ANTARCTICA (NG ENDURANCE) Active, immersive expedition travel Exploring Antarctica in an authentic expedition style, aboard an authentic expedition ship is an incomparable experience, and your guarantee of an in-depth encounter with all its wonders. Lindblad Expedition’s pioneering polar heritage and 50 years of experience navigating polar geographies is your assurance of safe passage in one of the wildest sectors of the planet. Have up-close, personal penguin encounters Travel with virtually any company to Antarctica, and you will see penguins. They are the citizens of the white continent, present in astounding numbers, and endlessly fascinating. Travel with Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic, however, and you’ll travel equipped for up-close, personal encounters—with a fleet of Zodiacs and kayaks to enable you to get closer. And a team of engaging experts that waiting around for returning parties. You’ll have a choice of enable you to spend more time enjoying penguin society, and activities each day, and the option to join the naturalist whose understand more of the adaptations that enable these interests mirror yours. Choice also includes opting to enjoy the remarkable animals to survive their environment. Take view from the bridge, the all-glass observation lounge, the advantage of all the superb photo ops You’ll have a National library or the chart room. To visit the fitness center with its Geographic photographer as your traveling companion, to panoramic windows, or ease into the sauna or a massage in the inspire you and provide tips in the field. And the services of a wellness center. -

The Plight of Our Planet the Relationship Between Wildlife Programming and Conservation Efforts

! THE PLIGHT OF OUR PLANET fi » = ˛ ≈ ! > M Photo: https://www.kmogallery.com/wildlife/2 = 018/10/5/ry0c9a1o37uwbqlwytiddkxoms8ji1 u f f ≈ f Page 1 The Plight of Our Planet The Relationship Between Wildlife Programming And Conservation Efforts: How Visual Storytelling Can Save The World By: Kelsey O’Connell - 20203259 In Fulfillment For: Film, Television and Screen Industries Project – CULT4035 Prepared For: Disneynature, BBC Earth, Netflix Originals, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, Etc. Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot express enough gratitude to everyone who believed in me on this crazy and fantastic journey; everything you have done has molded me into the person I am today. To my family, who taught me to seek out my own purpose and pursue it wholeheartedly; without you, I would have never taken the chance and moved to England for my Masters. To my professors, who became my trusted resources and friends, your endless and caring teachings have supported me in more ways than I can put into words. To my friends who have never failed to make me smile, I am so lucky to have you in my life. Finally, a special thanks to David Attenborough, Steve Irwin, Terri Irwin, Jane Goodall, Peter Gros, Jim Fowler, and so many others for making me fall in love with wildlife and spark a fire in my heart for their welfare. I grew up on wildlife films and television shows like Planet Earth, Blue Planet, March of the Penguins, Crocodile Hunter, Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, Shark Week, and others – it was because of those programs that I first fell in love with nature as a kid, and I’ve taken that passion with me, my whole life. -

Annual Summary of Reserve Management Needs for the 2021 Collaborative Research RFP Compiled October 2020

Annual Summary of Reserve Management Needs For the 2021 Collaborative Research RFP Compiled October 2020 Collaborative research projects supported by the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) Science Collaborative must address a management need of one or more reserves. This document is a compilation of the current management needs within NOAA’s reserve system. Management needs are submitted by reserve managers and updated on an annual basis. This reserve management needs summary supports the development of proposals in response to the 2021 NERRS Science Collaborative Request for Proposals. Potential applicants are encouraged to review the management needs described here and reach out to the point of contact listed for a reserve to discuss the reserve’s current needs and opportunities for collaboration. Project ideas that emerge after this document was developed and do not align perfectly with a specific management need statement, including project ideas that engage multiple reserves, can be considered for funding if the relevance and value to the reserve system and potential end users are well justified in the proposal. Science Collaborative focus areas and reserve management needs reflect both NOAA and reserve priorities set forth in the NERRS strategic plan (climate change, water quality and habitat protection) as well as individual reserve management needs at the local level. Science Collaborative Focus Areas: These management needs are consistent with one or several of the Science Collaborative focus areas, which are: ● Climate change: Research and monitoring related to biophysical, social, economic, and behavioral impacts of habitat change resulting from climate change and/or coastal development. ● Ecosystem services: Understanding how an ecosystem service approach and human dimensions research can be utilized to support the protection and restoration of estuarine systems. -

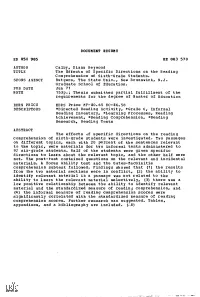

The Effects of Specific Directions on the Reading Comprehension of Sixth-Grade Students

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 050 905 RE 003 570 AUTHOR Calby, Diana Heywood TITLE The Effects of Specific Directions on the Reading Comprehension of Sixth-Grade Students. SPONS AGENCY Rutgers, The State Univ., New Brunswick, N.J. Graduate School of Education. PUB DATE Jun 71 NOTE 153p.; Thesis submitted partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Directed Reading Activity, *Grade 6, Informal Reading Inventory, *Learning Processes, Reading Achievement, *Reading Comprehension, *Reading Research, Reading Tests ABSTRACT The effects of specific directions on the reading comprehension of sixth-grade students were investigated. Two passages on different topics, each with 20 percent of the sentences relevant to the topic, were materials for two informal tests administered to 92 six-grade students. Half of the students were given specific directions to learn about the relevant topic, and the other half were not. The post-test contained questions on the relevant and incidental materials. A Focus Ability test and the Gates-MacGinitie comprehension subtest followed. Findings showed that(1) the results from the two material sections were in conflict,(2) the ability to identify relevant material in a passage was not related to the ability to learn the relevant material selectively,(3) there was a low positive relationship between the ability to identify relevant material and the standardized measure of reading comprehension, and (4) the informal measure of reading comprehension scores were significantly correlated with the standardized measure of reading comprehension scores. Further research was suggested. Tables, appendixes, and a bibliography are included.