Liminal Spaces at the Centre of Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Of The. Same City, Ifl. the Wes^ Riding of The. County Pjf Ypr,K, and Nprth

of the. same city, ifl. the wes^ riding of the. county ampton, and Peterborough and. the, 'Syston. and, pjf Ypr,k, and nprth riding of the,'county of York Peterborough Railways, at or near,, to. the station or one of them. at Peterborough,, in the parish pif Flettonj. in the. 'A branch railway, with all proper works, ap- county of, Huntingdon, and passing froni., in^ proaches, and conveniences connected therewith through, or into the several parishes, townships,, diverging froui th.e said main line at or near Steven- and extra-parochial and other places. following, age, in the parish of Stevenage, in the(county of H,ert or some of them, that is to say, Stiltpjj^ Folkes-. fprd, and to terminate at or n,ear tp, Potter-stree worth, Yaxley, Nprman Cross H^addon, Cft*estertjpn, Bedford, in the parishes of Saint Mary and Sain; Aljlwalton, O.verton Waterville or C.b,errj Ortpn^ John's Bedford, or one of them, in the county of Qverton, Longvijle or Long Orton. with. Bjptol-olt Bedford^; and passing from, in, through or into the Bridge, Farcett, Fletton, Woodstone, and IjStand- several parishes, to,wnships, anijl extra parochial or ground, in the county of Huntingdon: Peterbo- other places following, or some, of them, that is to, rough, Saint Jphn. the. Baptist in, the pity and; say, Stjeyenage, Fisher's Gr?en, T°dd.'s Qxeen, Tit- liberty of Peterbp.rpugh,, in tjhe. cpun.tjy pf. North- more Gireeh, Ipppjjitt.s otheijwisf? Saint Hippplyts, amptph, the precincts of Peterbprough Cathedral,, Little Wymondly, Much Wymondly. -

Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills at Risk Simon Hudson

Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills at Risk Simon Hudson Discovering Mills East of England Building Preservation Trust A project sponsored by 1 1. Introductory essay: A History of Mill Conservation in Cambridgeshire. page 4 2. Aims and Objectives of the study. page 8 3. Register of Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills page 10 Grade I mills shown viz. Bourn Mill, Bourn Grade II* mills shown viz. Six Mile Bottom Windmill, Burrough Green Grade II mills shown viz. Newnham Mill, Cambridge Mills currently unlisted shown viz. Coates Windmill 4. Surveys of individual mills: page 85 Bottisham Water Mill at Bottisham Park, Bottisham. Six Mile Bottom Windmill, Burrough Green. Stevens Windmill Burwell. Great Mill Haddenham. Downfield Windmill Soham. Northfield or Shade Windmill Soham. The Mill, Elton. Post Mill, Great Gransden. Sacrewell Mill and Mill House and Stables, Wansford. Barnack Windmill. Hooks Mill and Engine House Guilden Morden. Hinxton Watermill and Millers' Cottage, Hinxton. Bourn Windmill. Little Chishill Mill, Great and Little Chishill. Cattell’s Windmill Willingham. 5. Glossary of terms page 262 2 6. Analysis of the study. page 264 7. Costs. page 268 8. Sources of Information and acknowledgments page 269 9. Index of Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills by planning authority page 271 10. Brief C.V. of the report’s author. page 275 3 1. Introductory essay: A History of Mill Conservation in Cambridgeshire. Within the records held by Cambridgeshire County Council’s Shire Hall Archive is what at first glance looks like some large Victorian sales ledgers. These are in fact the day books belonging to Hunts the Millwrights who practised their craft for more than 200 years in Soham near Ely. -

Talking About John Clare

TALKING ABOUT JOHN CLARE RONALD BLYTHE TRENT BOOKS 1 TALKING ABOUT JOHN CLARE 2 3 Ronald Blythe Talking About John Clare Trent Editions 1999 4 By the same author A Treasonable Growth Immediate Possession The Age of Illusion Akenfield The View in Winter From the Headlands Divine Landscapes The Stories of Ronald Blythe Private Words: Letters and Diaries from the Second World War Word from Wormingford Published by Trent Editions 1999 Trent Editions Department of English and Media Studies The Nottingham Trent University Clifton Lane Nottingham NG11 8NS Copyright (c) Ronald Blythe The cover illustration is a hand-tinted pen and ink drawing of Selborne, by John Nash, by kind permission of the John Nash Estate. The back cover portrait of Ronald Blythe is by Richard Tilbrook. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Printed in Great Britain by Goaters Limited, Nottingham ISBN 0 905 488 44 X 5 CONTENTS PREFACE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND PRINCIPAL SOURCES I. AN INHERITED PERSPECTIVE II. ‘SOLVITUR AMBULANDO’: CLARE AND FOOTPATH WALKING III.CLARE IN HIDING IV. CLARE IN POET’S CORNER, WESTMINSTER ABBEY V.CLARE’S TWO HUNDREDTH BIRTHDAY VI. THE DANGEROUS IDYLL VII.THE HELPSTON BOYS VIII. THOMAS HARDY AND JOHN CLARE IX.‘NOT VERSE NOW, ONLY PROSE!’ X.RIDER HAGGARD AND THE DISINTEGRATION OF CLARE’S WORLD XI. EDMUND BLUNDEN AND JOHN CLARE XII.PRESIDENTIAL FRAGMENTS XIII. KINDRED SPIRITS XIV. COMMON PLEASURES INDEX OF NAMES 6 For R.S. -

Brampton Park Brampton

Brampton Park Brampton A fine collection of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom homes in Brampton PE28 4ZA Brampton – local area A thriving village with something for everyone Brampton Park is a brand new development 5,000 residents and enjoys a host of There is an array of open spaces nearby, such of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom homes, situated in the amenities and facilities including shops, as the River Great Ouse, Portholme Meadow, Cambridgeshire village of Brampton, close to pubs, restaurants, doctors, dentists, Hinchingbrooke Country Park, Brampton Huntingdon and within commuting distance a nursery and primary school. Still retaining Wood and Brampton Golf Course, while of Peterborough, Cambridge and London. its village green, many historic buildings the excitement of a day at the races can be and an ancient parish church, of particular enjoyed at nearby Huntingdon Racecourse. Here, Linden Homes is offering a wide range interest are Brampton’s connections with the of properties, suitable for differing needs and diarist Samuel Pepys. Brampton enjoys budgets, but all featuring great design, sleek a number of meeting halls, serving as venues contemporary kitchens, stylish bathrooms for a host of local events and community and high quality fittings throughout. activities, plus playing fields that include Brampton is a thriving village of around a children’s play area and skate park. Brampton – further afield MILES TO Close to Huntingdon, 1.4 A1 with wonderful countryside nearby MILES TO 1.5 A14 Famous for its connections with Oliver a purpose built venue for exhibitions, MILES TO Cromwell and Samuel Pepys, Huntingdon is concerts and theatre. -

Appendix 1 Water Resource Zone Characteristics Contents

Drought Plan 2019 Appendix 1 Water Resource Zone Characteristics Contents Water Resource Zone Characteristics 3 Area 1: Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire 5 Central Lincolnshire 5 Bourne 7 East Lincolnshire 8 Nottinghamshire 10 South Lincolnshire 11 Area 2: Ruthamford 12 Ruthamford Central 12 Ruthamford North 13 Ruthamford South 15 Ruthamford West 17 Area 3: Fenland 18 North Fenland 18 South Fenland 19 Area 4: Norfolk 20 Happisburgh 20 North Norfolk Coast 21 North Norfolk Rural 23 Norwich and The Broads 25 South Norfolk Rural 27 Area 5: East Sufflok and Essex 28 Central Essex 28 East Suffolk 29 South Essex 31 Area 6: Cambridgeshire and West Suffolk 33 Cheveley, Ely, Newmarket, Sudbury, Ixworth, and Bury Haverhill 33 Thetford 36 Area 7: Hartlepool 37 Hartlepool 37 2 Water Resource Zone Characteristics The uneven nature of climate, drought, growth and List of WRMP 2019 WRZs, in order of discussion: environmental impacts across our region means we have developed Water Resource Zones (WRZs). WRZs Area 1: Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire are the geographical areas used to develop forecasts Central Lincolnshire of supply and demand and supply-demand balances. Bourne The WRZ describes an area within which supply infrastructure and demand centres are linked such East Lincolnshire that customers in the WRZ experience the same risk Nottinghamshire of supply failure. These were reviewed in the Water South Lincolnshire Resources Management Plan (WRMP) 2019 and have changed since the last WRMP and Drought Plan. Area 2: Ruthamford Ruthamford Central Overall, we have increased the number of WRZs from 19 at WRMP 2015 to 28 for WRMP 2019, including Ruthamford North the addition of South Humber Bank which is a non- Ruthamford South potable WRZ that sits within Central Lincolnshire. -

The Pilsgate Conservation Area Appraisal

PILSGATE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL REPORT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by: Growth & Regeneration, Peterborough City Council Date: June 2017 431 PILSGATE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL DRAFT REPORT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Contents: 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Scope of the appraisal 1 3.0 Planning Policy Context 2 3.1 Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 2 3.2 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) 2 3.3 Local Development Framework, Core Strategy 2 4.0 Summary of Special Interest 3 5.0 Location and boundary 3 6.0 Geology and landscape setting 4 7.0 Brief History of the Settlement 5 8.0 Archaeology 7 9.0 Character and Appearance 8 9.1 Spatial character 8 9.2 Architecture and building materials 11 9.3 Key views 14 9.4 Trees, hedgerows, verges and stone walls 14 9.5 Street furniture and services 16 9.6 Building uses 16 10.0 Historic buildings 17 10.1 Listed buildings 17 10.2 Positive Unlisted Buildings 17 11.0 Management Plan 18 11.1 Planning policies and controls 18 11.2 Conservation area boundary 19 11.3 Historic buildings 20 11.4 Stone walls 20 11.8 Highways and street furniture 20 11.6 Tree planting 20 12.0 References 21 13.0 Useful Contacts 21 Appendix 1 Pilsgate Townscape Analysis Map 432 1.0 Introduction The Pilsgate Conservation Area was designated in 1979. This document aims to fulfil the City Council’s statutory duty to ‘draw up’ and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of the conservation area as required by the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 and provide planning guidance in support of Policy PP17 of the Peterborough Planning Policies Development Plan Document (DPD). -

Northamptonshire. [Kell'''s

28 BARNACK. NORTHAMPTONSHIRE. [KELL'''S BARNAOK RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL. r887, amalgamat~d with Barnack, and the whole desig :Met>ts at the Stamford Workhouse monthly at 12 noon. nated the hamlet of Barnack. The children attend The district comprises the parishes of; Bainton, Bar Barnack school. nack, Southorpe, Stamford Baron St. Martin With Wall Letter Box cleared "lit 7 & 11.15 a.m. & 6 p.m. out, Thornhaugh, Ufford, Wansford, Wittering & -week days only . Wothorpe, being the Northants parishes in Stamford, Lincolnshire, Union. The area is 15,256 acres; rate SOUTHORPE is a civil parish, 1 mile south from able value, £22,752; the population in 19II was 2,097. Barnack and 5 miles from Stamford. The area is 1,88r Chairman, Marquis of Exeter, Burleigh House, Stamford acres; rateable value, £1,790; the population in 1911 was 183. Officials. • The children attend Barnack school Clerk, Richard English, 40 Broad street, Stamford Treasurer, John Bayldon, Barclay & Company's Bank, Wall Letter .Box cleared at 7.30 a.m. & 5.40 p.m. week Stamford days only ~Iedical Officar of Health, Thomas Porter Greenwood Police Station, Harry King, sergeant in charge L.R.C.P.Edin., M.R.C.S.Eng. 36 St. Mary's street, Public Elementary School (mixed), for 125 children; Stamford average attendance, 100 ; Charles B. Allerton, mastel!- Surveyor, Alfred Cave, Barnack Carrier. Jesse- Knipe, to Stamford, daily Sanitary Inspector, J. G. Bailey, Sbamford Railway Stations. PILSGATE, a hamlet, nearly 3 miles from Stamford. Great Northern, George Brader, station master "·as by a Local Government Order, dated March 25, Midland, Albert H. -

Supply Forecast

WRMP 2019 Technical Document: Supply Forecast December 2019 Introduction WRMP Sustainability Selecting Climate WRMP Links Other Water 2019 supply Appendix 1: Appendix 2: 2019 supply changes the design change to drought impacts transfers forecast Hall intake Stochastic forecast impact drought impact plan River Trent drought approach assessment assessment analysis and selection This is a technical report that supports our WRMP submission. This report provides an overview of our supply forecast. It explains the methodologies we have used to calculate deployable output and assess impacts from sustainability reductions, climate change and severe drought. 2 Introduction WRMP 2019 Sustainability Design Climate WRMP links Other Water 2019 Supply Appendix 1: Appendix 2: Supply Changes Drought Change to Drought impacts Transfers Forecast Hall intake Stochastic Forecast Impact Impact Impact Plan River Trent drought Approach Assessment Assessment Assessment analysis and selection Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Overview 6 1.2 Developing our Supply Forecast 7 2. WRMP 2019 Supply Forecast Approach 10 2.1 Hydrological yield updates 10 2.2 DO constraint review 12 2.3 DO assessment approach 13 2.4 Moving to a system model 14 2.5 Model build 14 2.6 Baseline DO assessment methodology 15 2.7 WTW DO and constraining factors 16 2.8 Baseline DO changes since WRMP 2015 23 3. Sustainability Changes Impact Assessment 24 3.1 WFD no deterioration 24 3.2 AMP7 sustainability reductions 25 3.3 Modelling report 25 3.4 Eel and Fish passage 28 3.5 Future exports 28 4. Design Drought Impact Assessment 29 4.1 Increasing resilience to severe drought 29 4.2 Severe drought development and selection 30 4.3 Severe drought impact assessment 30 5. -

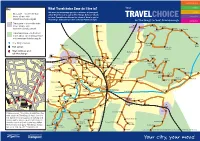

What Travelchoice Zone Do I Live In? We Want to Encourage You to Use Forms of Transport Bus Zone – to See the Bus Other Than the Car to Get to the King’S School

Key What Travelchoice Zone do I live in? We want to encourage you to use forms of transport Bus zone – to see the bus other than the car to get to The King’s School. Check times please visit out our Travelchoice Zones for ideas of how to get to www.travelchoice.org.uk The King’s School if you live outside Peterborough. to The King’s School, Peterborough Train zone – to see the train Morton times please visit Spalding Weston Whaplode Spalding Holbeach www.travelchoice.org.uk Fleet Hargate Moulton Bourne Car-share zone – to find out more about car sharing please Weston Hills Long Sutton visit www.travelchoice.org.uk Thurlby Cowbit The King’s School Moulton to Oakham Chapel Sutton Bridge Rail station Holbeach St. Johns Town with bus and Brotherhouse Bar rail interchange to Oakham Stamford Uffington Whaplode Market Deeping Drove Tinwell Stamford Maxey Deeping St. James Sutton St. Edmund The King’s Shepeau Stow G Bainton Northborough Crowland Abbey ra School Easton on the Hill Pilsgate nv Holbeach ile Collyweston Barnack Etton Peakirk Milking Drove Nook Gedney Bu to Uppingham Helpston rg St Wittering Hill Gorefield hl ree Ufford Glinton Newborough ey t R to o Duddington Lowestoft ad Southorpe Leverington Throckenholt Church End Thornhaugh Upton Parson Marholm Werrington Eye Green Drove Wisbech Wisbech d d Wansford Murrow St. Mary a a Thorney y o King’s Cliffe o Sutton Ailsworth Eye a Yarwell R R w Castor Peterborough k d n Apethorpe l r a Nassington a o o Water PETERBOROUGH Guyhirn r Woodnewton c P Newton North Side B n River Nene i Fotheringhay 8 L Elton W Southwick Chesterton e s t to Eaglethorpe Whittlesey g Milton Keynes Coates a Cotterstock Tansor Farcet Bus station te Glapthorne Warmington Eastrea Whittlesea Turves Rail station Queensgate Yaxley March Oundle Folksworth March Stoke Doyle Lutton Pondersbridge e Polebrook n Stilton It takes around 15 minutes to walk from the e N r train station to The King’s School. -

4 Ceremonial Practice and Mortuary Ritual

4 Ceremonial Practice and Mortuary Ritual Old customs O I love the sound correlation between the importance of an However simple they may be event to those taking part in it, and its What ere wi time has sanction found surviving signature. Durable objects remain Is welcome & clear to me visible, and so naturally figure prominently in the archaeological interpretation of a John Clare, The Shepherd’s Calendar: December monument, but this can lend them a dispro portionate weight of importance. A festival 4.1 The forms and uses of at which a hundred people prayed, danced, monuments sang and offered sacrifices for a week may have left no trace other than enhanced phos The modest scale and changing character of phate levels; a funeral attended by six for the the monuments at Raunds are a reminder of space of half a day may have left a grave and the intimacies of people’s lives as they built a set of grave goods. and used this landscape. There was no preconceived intention or master plan 4.1.1 The early 4th millennium behind its long-term development, no grandiose vision obediently reproduced by There is every indication that people had generation after generation of peoples. ceased to live at the West Cotton confluence Instead, the history of the river valley is char by the time the first monuments were built, acterised by more fleeting occasions of and that the rest of the excavated area was concretization, or short-term episodes not occupied at all until after they had gone during which the beliefs and practices of out of use. -

Cycle from the Green Wheel

Beyond N e Essendine w R i v v e e r r Drain South Drove Greatford Langtoft Gated road Crowland Ryhall ut Market Barholm d C tfor Deeping rea Tolethorpe G Hall ©Burghley House Busy at commuting ©Vivacity times Croyland Abbey Little Tallington Lakes Leisure 6 Centre Water Sports A1 Casterton Centre E6 Nene Valley Railway £8.00 - £14.50 Rtn West Places to visit Deeping CC Experience all the live sights and sounds of the golden age of steam. Take a ride on the Map Ref Maxey 7½ miles of track that takes you through the Tallington Green Wheel Route beautiful Nene Valley to Wansford. Also home E7 Peterborough Free. Donations welcome Uffington A 1 16 5 Northborough 3 Stamford A 7 to ‘Thomas’, the children’s favourite engine. 0 Cathedral 1 CC A Tel: 01780 784444 or visit www.nvr.org.uk One of the best examples of a Norman Cut xey Cathedral in the country. Also the resting place Ma Peakirk N16 Norman Cross Free Stamford Etton of Henry VIII’s first wife Katherine of Aragon. Station Newborough Visit the site of the first Napoleonic prisoner Burghley Bainton A Park 1 Glinton of war camp, see the Norman Cross itself and I7 Bluebell Millennium Turf Maze Free See other side for more detail Wothorpe look round the art gallery. Burghley A turf maze in the style of the Minotaur’s House Pilsgate Helpston labyrinth. N12 Oundle John Clare Memorial Sobrite Barnack and House Spring Easton Rice A 40 minute cycle from the Green Wheel. on the Wood B4 BMX track Free.