6 - Burgin Final.Docx (Do Not Delete) 3/21/16 10:31 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Rio Grande Compact of 1938

The Rio Grande Compact: Douglas R. Littlefield received his bache- Its the Law! lors degree from Brown University, a masters degree from the University of Maryland and a Ph.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1987. His doc- toral dissertation was entitled, Interstate The History of the Water Conflicts, Compromises, and Com- Rio Grande pacts: The Rio Grande, 1880-1938. Doug Compact heads Littlefield Historical Research in of 1938 Oakland, California. He is a research histo- rian and consultant for many projects throughout the nation. Currently he also is providing consulting services to the U.S. Department of Justice, Salt River Project in Arizona, Nebraska Department of Water Resources, and the City of Las Cruces. From 1984-1986, Doug consulted for the Legal Counsel, New Mexico Office of the State Engineer, on the history of Rio Grande water rights and interstate apportionment disputes between New Mexico and Texas for use in El Paso v. Reynolds. account for its extraordinary irrelevancy, Boyd charged, by concluding that it was written by a The History of the congenital idiot, borrowed for such purpose from the nearest asylum for the insane. Rio Grande Compact Boyds remarks may have been intemperate, but nevertheless, they amply illustrate how heated of 1938 the struggle for the rivers water supplies had become even as early as the turn of the century. And Boyds outrage stemmed only from battles Good morning. I thought Id start this off on over water on the limited reach of the Rio Grande an upbeat note with the following historical extending just from southern New Mexicos commentary: Mesilla Valley to areas further downstream near Mentally and morally depraved. -

History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Law of the Rio Chama The Utton Transboundary Resources Center 2007 History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation Susan Kelly UNM School of Law, Utton Center Iris Augusten Joshua Mann Lara Katz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/uc_rio_chama Recommended Citation Kelly, Susan; Iris Augusten; Joshua Mann; and Lara Katz. "History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation." (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/uc_rio_chama/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Utton Transboundary Resources Center at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law of the Rio Chama by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. SUSAN KELLY, IRIS AUGUSTEN, JOSHUA MANN & LARA KATZ* History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation" ABSTRACT Nearly all of the dams and reservoirson the Rio Grandeand its tributaries in New Mexico were constructed by the federal government and were therefore authorized by acts of Congress. These congressionalauthorizations determine what and how much water can be stored, the purposesfor which water can be stored, and when and how it must be released. Water may be storedfor a variety of purposes such as flood control, conservation storage (storing the natural flow of the river for later use, usually municipal or agricultural),power production, sediment controlfish and wildlife benefits, or recreation. The effect of reservoir operations derived from acts of Congress is to control and manage theflow of rivers. -

Rio Grande Project

Rio Grande Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents Rio Grande Project.............................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Project Authorization.....................................................6 Construction History .....................................................7 Post-Construction History................................................15 Settlement of the Project .................................................19 Uses of Project Water ...................................................22 Conclusion............................................................25 Suggested Readings ...........................................................25 About the Author .............................................................25 Bibliography ................................................................27 Manuscript and Archival Collections .......................................27 Government Documents .................................................27 Articles...............................................................27 Books ................................................................29 Newspapers ...........................................................29 Other Sources..........................................................29 Index ......................................................................30 1 Rio Grande Project At the twentieth -

CRWR Online Report 11-02

CRWR Online Report 11-02 Water Planning and Management for Large Scale River Basins: Case of Study of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Transboundary Basin by Samuel Sandoval-Solis, Ph.D. Daene C. McKinney, PhD., PE May 2011 CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN WATER RESOURCES Bureau of Engineering Research • The University of Texas at Austin J.J. Pickle Research Campus • Austin, TX 78712-4497 This document is available online via World Wide Web at http://www.crwr.utexas.edu/online.shtml Copyright by Samuel Sandoval Solis 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Samuel Sandoval Solis Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Water Planning and Management for Large Scale River Basins Case of Study: the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Transboundary Basin Committee: Daene C. McKinney, Supervisor Randall J. Charbeneau David R. Maidment David J. Eaton Bryan R. Roberts Water Planning and Management for Large Scale River Basins Case of Study: the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Transboundary Basin by Samuel Sandoval Solis, B.S.; M.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2011 Dedication Dedico esta tesis doctoral a Sil, mi amor, mi esposa, mi alma gemela, mi completo, mi fuerza, mi aliento, mi pasión; este esfuerzo te lo dedico a ti, agradezco infinitamente tu amor, paciencia y apoyo durante esta aventura llamada doctorado, ¡lo logramos! A mis padres Jesús y Alicia, los dos son un ejemplo de vida para mi, los amo con toda mi alma Acknowledgements I would like to express my endless gratitude to my advisor, mentor and friend Dr. -

2002 Federal Register, 67 FR 39205; Centralized Library: U.S. Fish

Thursday, June 6, 2002 Part IV Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Rio Grande Silvery Minnow; Proposed Rule VerDate May<23>2002 18:22 Jun 05, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\06JNP3.SGM pfrm17 PsN: 06JNP3 39206 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 109 / Thursday, June 6, 2002 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ADDRESSES: 1. Send your comments on fishes in the Rio Grande Basin, this proposed rule, the draft economic occurring from Espan˜ ola, NM, to the Fish and Wildlife Service analysis, and draft EIS to the New Gulf of Mexico (Bestgen and Platania Mexico Ecological Services Field Office, 1991). It was also found in the Pecos 50 CFR Part 17 2105 Osuna Road NE, Albuquerque, River, a major tributary of the Rio RIN 1018–AH91 NM, 87113. Written comments may also Grande, from Santa Rosa, NM, be sent by facsimile to (505) 346–2542 downstream to its confluence with the Endangered and Threatened Wildlife or through the Internet to Rio Grande (Pflieger 1980). The silvery and Plants; Designation of Critical [email protected]. You may also minnow is completely extirpated from Habitat for the Rio Grande Silvery hand-deliver written comments to our the Pecos River and from the Rio Grande Minnow New Mexico Ecological Services Field downstream of Elephant Butte Reservoir Office, at the above address. You may and upstream of Cochiti Reservoir AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, obtain copies of the proposed rule, the (Bestgen and Platania 1991). -

Border Wars & the New Texas Navy

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2013 Border Wars & The New Texas Navy: International Treaties, Waterways, And State Sovereignty After Arizona v. United States Bill Piatt St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Rachel Ambler Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bill Piatt and Rachel Ambler, Border Wars & The New Texas Navy: International Treaties, Waterways, And State Sovereignty After Arizona v. United States, 15 Scholar 535 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BORDER WARS & THE NEW TEXAS NAVY: INTERNATIONAL TREATIES, WATERWAYS, AND STATE SOVEREIGNTY AFTER ARIZONA V. UNITED STATES BILL PIATT* RACHEL AMBLER** "Texas has yet to learn submission to any oppression, come from what source it may." -Sam Houston' * Dean (1998-2007) and Professor of Law (1998-Present), St. Mary's University School of Law. ** Student at St. Mary's University School of Law and Law Clerk at Pullman, Cappuccio, Pullen & Benson, LLP, San Antonio, Texas. 1. Samuel Houston, of Texas, In reference to the Military Occupation of Santa Fe and in Defence of Texas and the Texan Volunteers in the Mexican War, Address Before the Senate (June 29, 1850), in DAtiy NAIONAL INTELLIGENCER (Washington, D.C.), Oct. -

First Interim Report of the Special Master

No. 141, Original ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF NEW MEXICO and STATE OF COLORADO, Defendants. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On New Mexico’s Motion To Dismiss Texas’s Complaint And The United States’ Complaint In Intervention And Motions Of Elephant Butte Irrigation District And El Paso County Water Improvement District No. 1 For Leave To Intervene --------------------------------- --------------------------------- FIRST INTERIM REPORT OF THE SPECIAL MASTER --------------------------------- --------------------------------- A. GREGORY GRIMSAL Special Master 201 St. Charles Avenue Suite 4000 New Orleans, LA 70170 (504) 582-1111 February 9, 2017 ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities ............................................. xiv I. Introduction ............................................... 4 II. Background Principles of Water Law ........ 9 A. The Doctrine of Prior Appropriation .... 9 B. The Doctrine of Equitable Apportion- ment ..................................................... 23 III. The Historical Context: Events Leading to the Ratification of the 1938 Compact ........ 31 A. The Geography of the Upper Rio Grande Basin ....................................... 32 B. The Natural -

Habitat Use of Rio Grande Silvery Minnow

HABITAT USE OF RIO GRANDE SILVERY MINNOW Robert K. Dudley and Steven P. Platania Division of Fishes, Museum of Southwestern Biology Department of Biology, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131 submitted to: David L. Propst New Mexico Department of Game and Fish State Capitol, Villagra Building P.O. box 25112 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 and James P. Wilber United States Bureau of Reclamation 505 Marquette NW, Suite 1313 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102 17 December 1997 Dudley & Platania 1997. Habitat use of Rio Grande silvery minnow. FINAL-DECEMBER 1997 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The primary purpose of this study was to characterize habitat use of Rio Grande silvery minnow at two sites, Rio Rancho and Socorro, in the Middle Rio Grande, NM. Habitat use was determined through a series of measurements of depth, velocity and substrate taken in the area where fish were collected. Habitat availability was measured along permanent transects at each site. Rio Grande silvery minnow was relatively abundant at both sampling localities, but was more numerous and comprised a greater percentage of the total catch at Socorro than at Rio Rancho. Red shiner, western mosquitofish, flathead chub, fathead minnow, longnose dace and white sucker were present in moderate numbers at both sites, but the other 12 species collected during the study accounted for less than 5% of the total catch. Although the abundance of fish varied widely across time within sites, the majority of all fish were collected at the Socorro, NM site. The mesohabitats most commonly occupied by all size-classes of Rio Grande fishes were low water velocity habitats over small substrata. -

History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation

Volume 47 Issue 3 Symposium on New Mexico's Rio Grande Reservoirs Summer 2007 History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation Susan Kelly Iris Augusten Joshua Mann Lara Katz Recommended Citation Susan Kelly, Iris Augusten, Joshua Mann & Lara Katz, History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation, 47 Nat. Resources J. 525 (2007). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol47/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. SUSAN KELLY, IRIS AUGUSTEN, JOSHUA MANN & LARA KATZ* History of the Rio Grande Reservoirs in New Mexico: Legislation and Litigation" ABSTRACT Nearly all of the dams and reservoirson the Rio Grandeand its tributaries in New Mexico were constructed by the federal government and were therefore authorized by acts of Congress. These congressionalauthorizations determine what and how much water can be stored, the purposesfor which water can be stored, and when and how it must be released. Water may be storedfor a variety of purposes such as flood control, conservation storage (storing the natural flow of the river for later use, usually municipal or agricultural),power production, sediment controlfish and wildlife benefits, or recreation. The effect of reservoir operations derived from acts of Congress is to control and manage theflow of rivers. When rivers cross state or other jurisdictionalboundaries, the states are very mindful of the language in the congressional authorization. -

Sustainability of Engineered Rivers in Arid Lands: Euphrates-Tigris and Rio Grande/Bravo

Sustainability of Engineered Rivers in Arid Lands: Euphrates-Tigris and Rio Grande/Bravo 190 Policy Research Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs Policy Research Project Report Number 190 Sustainability of Engineered Rivers in Arid Lands: Euphrates-Tigris and Rio Grande/Bravo Project Directed by Aysegül Kibaroğlu Jurgen Schmandt A report by the Policy Research Project on Sustainability of Euphrates-Tigris and Rio Grande/Bravo 2016 The LBJ School of Public Affairs publishes a wide range of public policy issue titles. ISBN: 978-0-89940-818-7 ©2016 by The University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. No part of this publication or any corresponding electronic text and/or images may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover design by Lauren R. Jahnke Maps created by the Houston Advanced Research Center Policy Research Project Participants Graduate Students Deirdre Appel, BA (International Relations and Public Policy), University of Delaware; Master of Global Policy Studies student, LBJ School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin Jose Balledos, BS (Physics), University of San Carlos; Master of Global Policy Studies student, LBJ School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin (Fall term only) Christine Bonthius, BA (Physical Geography), University of California, Las Angeles; Ph.D. student (Geography and the Environment), -

Managing the Upper Rio Grande: Old Institutions, New Players

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Boundaries and Water: Allocation and Use of a Shared Resource (Summer Conference, June 1989 5-7) 6-5-1989 Managing the Upper Rio Grande: Old Institutions, New Players Steven J. Shupe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/boundaries-and-water-allocation- and-use-of-shared-resource Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Contracts Commons, Courts Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Hydrology Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Litigation Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Shupe, Steven J., "Managing the Upper Rio Grande: Old Institutions, New Players" (1989). Boundaries and Water: Allocation and Use of a Shared Resource (Summer Conference, June 5-7). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/boundaries-and-water-allocation-and-use-of-shared-resource/7 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. Steven J. Shupe, Managing the Upper Rio Grande: Old Institutions, New Players, in BOUNDARIES AND WATER: ALLOCATION AND USE OF A SHARED RESOURCE (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law 1989). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. -

Classifi Cation

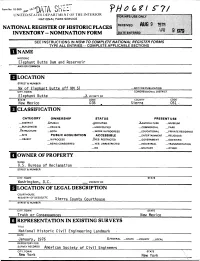

Form No. 10-300 (ptl* '" DATAJLJ/'A i f \ O UNITED STATES DEPARTMENI OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES • INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM mm SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir_______________________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER of Elephant Butte off NM 51 NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Elephant Butte ____. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New Mexico 035 Sierra 051 CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT .^PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED -^AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK -^STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME U.S. Bureau of Reclamation STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Washington, D.C. VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Sierra County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Truth or Consequences New Mexico 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark DATE January, 1976 X.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS American Society of Civil Engineers CITY, TOWN STATE New York New York DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED -X.UN ALTERED -X.ORIGINALSITE J^GOOD —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE With a capacity of over two million acre feet, the Elephant Butte Reservoir is one of the largest water storage facilities in the Southwest.