21-26. Hollywood UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

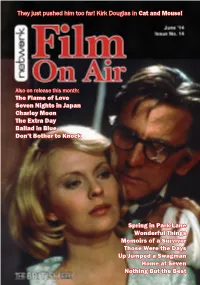

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

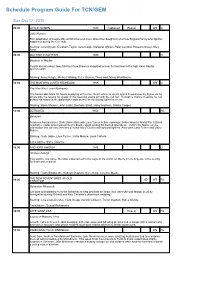

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Oct 17, 2010 06:00 LITTLE WOMEN 1949 Captioned Repeat WS G Little Women Film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's beloved novel about four daughters of a New England family who fight for happiness during the Civil War. Starring: June Allyson, Elizabeth Taylor, Janet Leigh, Margaret O'brien, Peter Lawford, Rossano Brazzi, Mary Astor 08:30 MAYTIME IN MAYFAIR 1949 G Maytime In Mayfair Penniless man-about-town Michael Gore-Brown is delighted to hear he has been left a high-class Mayfair fashion salon. Starring: Anna Neagle, Michael Wilding, Peter Graves, Thora Hird, Mona Washbourne 10:35 THE MAN WHO LOVED REDHEADS 1955 WS G The Man Who Loved Redheads The honourable Mark St. Neots is playing with some chums when he meets and is bowled over by Sylvia. As he grows older he retains his image of this beautiful young girl with the red hair. Through a chance meeting, he can pursue his career in the diplomatic corps as well as the young ladies he meets. Starring: Moira Shearer, John Justin, Denholm Elliott, Harry Andrews, Gladys Cooper 12:40 BETRAYED 1954 PG Betrayed Academy Award winner Clark Gable stars with Lana Turner in this espionage thriller about a World War II Dutch resistance leader who must uncover a double agent among his trusted operatives... before the Nazis receive information that will cost the lives of hundreds of Dutch underground fighters. Also stars Lana Turner and Victor Mature. Starring: Clark Gable, Lana Turner, Victor Mature, Louis Calhern Cons.Advice: Some Violence 15:00 ANCHORS AWEIGH 1945 G Anchors Aweigh Two sailors, one naive, the other experienced in the ways of the world, on liberty in Los Angeles, is the setting for this movie musical. -

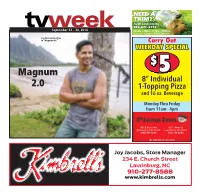

Magnum P.I.” Carry out Weekdaymanager’S Spespecialcial $ 2 Medium 2-Topping Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5And 16Each Oz

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 22 - 28, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 Jay Hernandez stars in “Magnum P.I.” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday from 11am - 4pm 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 22, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Back to the well: ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to television with CBS reboot By Kenneth Andeel er One,” 2018) in the role of Higgins, dependence on sexual tension in TV Media the straight woman to Magnum’s the new formula. That will ultimate- wild card, and fellow Americans ly come down to the skill and re- ame the most famous mustache Zachary Knighton (“Happy End- straint of the writing staff, however, Nto ever grace a TV screen. You ings”) and Stephen Hill (“Board- and there’s no inherent reason the have 10 seconds to deduce the an- walk Empire”) as Rick and TC, close new dynamic can’t be as engrossing swer, and should you fail, a shadowy friends of Magnum’s from his mili- as its prototype was. cabal of drug-dealing, bank-rob- tary past. There will be other notable cam- bing, helicopter-hijacking racketeers The pilot for the new series was eos, though. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Press to Go There to Cover It

PUBLICITY MATERIALS Tasmanian Devil: The Fast and Furious Life of Errol Flynn CONTACT PRODUCTION COMPANY 7/32 George Street East Melbourne 3002 Victoria AUSTRALIA Tel/Fax: 0417 107 516 Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE PRODUCER / PRODUCER Sharyn Prentice PRODUCER Robert deYoung DIRECTOR Simon Nasht EDITOR Karen Steininger Tasmanian Devil: The Fast and Furious Life of Errol Flynn BILLING / TWO LINE SYNOPSIS Tasmanian Devil: The Fast and Furious Life of Errol Flynn Errol Flynn remains one of the most fascinating characters ever to work in Hollywood. Remembered as much for his scandals as his acting, there was another side to Errol: writer, war reporter and even devoted family man. THREE PARAGRAPH SYNOPSIS Tasmanian Devil: The Fast and Furious Life of Errol Flynn Fifty years after his death, people are still fascinated by Errol Flynn. The romantic star of dozens of Hollywood movies, Flynn’s real life was in fact far more adventurous than any of his films. In a life dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure, Flynn became notorious for his love affairs, scandals and rebellious nature. But there was another, much less well known side to his character. He was a fine writer, both of novels and journalism, wrote well reviewed novels and reported from wars and revolutions. Among his scoops was the first interview with the newly victorious Fidel Castro who Flynn tracked down in his mountain hideaway in Cuba. In Tasmanian Devil we discover the unknown Flynn, from his troubled childhood in Tasmania to his death, just fifty years later, in the arms of his teenage lover. We hear from his surviving children, friends and colleagues and discover an amazing life of almost unbelievable events. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Catalogue-Light-A5.Pdf

An introduction (GLCD 5101) Gateway To The West (Farnon) - QUEEN’S HALL LIGHT ORCH./ROBERT FARNON; Going For A Ride (Torch) - SIDNEY TORCH AND HIS ORCH.; With A Song In My Heart (Rodgers, Hart) - ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCH.; Heykens’ Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin) - RON GOODWIN & HIS ORCH.; Martinique (Warren) - RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCH.; Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips) - CHARLES WILLIAMS & HIS CONCERT ORCH.; Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose) - DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCH.; Out Of This World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer) - MANTOVANI & HIS ORCH.; Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran) - L’ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; Festive Days (Ancliffe) - LONDON PROMENADE ORCH./ WALTER COLLINS; Ha’penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green) PHILIP GREEN & HIS ORCH.; Tropical (Gould) - MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCH.; Puffin’ Billy (White) - DANISH STATE RADIO ORCH./HUBERT CLIFFORD; First Rhapsody (Melachrino) - MELACHRINO ORCH./GEORGE MELACHRINO; Fantasie Impromptu in C Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon) KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; London Bridge March (Coates) - NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY ORCH./JOSEPH LEWIS; Mock Turtles (Morley) - QUEEN’S HALL LIGHT ORCH./ROBERT FARNON; To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke) - PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCH.; Plink, Plank, Plunk! (Anderson) - LEROY ANDERSON & HIS ‘POPS’ CONCERT ORCH.; Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith) - PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCH.; Vision in Velvet (Duncan) - NEW CONCERT ORCH./JACK LEON; Grand Canyon (van der Linden) - DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCH.; Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. Young) - FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCH.; Dainty Lady (Peter) - REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCH.; Bandstand (‘Frescoes’ Suite) (Haydn Wood) - NEW CONCERT ORCH./SERGE KRISH The 1940s (GLCD 5102) Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

50Th Reunion

Class of 1959 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1959 Marcia Margulies Abramson* Helen Coonley Colcord Carol Grossman Gollob* Harriet Turteltaub Abroms Rita Zimmerman Collier Janet McCreery Gregg Hillary de Mandeville Adams Justine (Merle) Riskind Janice Probasco Griffiths* (Judith Snyder) Coopersmith Janet Hallenborg* Valerie Reichman Aspinwall* Irene Kerman Cornman* Mary Lynn Hanley Jessica Falikman Attiyeh Ellen Count Linda Wittcoff Hanrahan Rona King Bank Ann Elliott Criswell Barbara Hanson Elisabeth Posselt Barker Diane Deckard Joan Cross Hawkins Patricia Beatty Jane Vanderploeg Deckoff Judith Silverman Herschman Joan Waltrich Blake* Linda Monheit Denholtz Elaine Tabor Herdtfelder Deirdre Cooney Bonifaz Abby DuBow-Casden Pamela Hill Alison Wilson Bow Vijaya Gulhati Duggal Arlene Kronenberg Hoffman Rebecca Stout Bradbury Elizabeth Partridge Durant Jill Hoffman Rosalie Posner Brinton Ellen Hirsch Ephron* E. Joan Allan Horrocks Nancy Schoenbrun Burkey Margaret Fairlie-Kennedy Mary Earhart Horton Heather Roden Cabrera Helaine Feinstein Fortgang* Jane Leoncavallo Hough Carol Berry Cameron Barbara Kyle Foster Wilda Darby Hulse* June Allan Carter Sally Foster Marina Mirkin Jacobs Barrie Rabinowitz Cassileth Amy Sweedler Friedlander Roberta Forrest Jacobson Ann Turner Chapin Joan Trooboff Geetter Julie Hirsh Jadow France Berveiller Choa Mary Jane Allison Gilbert Paula Cassetta Jennings Ann Avery Clarke Phyllis Saretsky Gitlin Carolyn Wyte Jordan Katharine Durant Cobey Helen Trubek Glenn Sandra Siegel Kaplan Margot Bowes Cody* James -

ANNOUNCEMENT from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

ANNOUNCEMENT from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559-6000 PUBLICATION OF FIFTH LIST OF NOTICES OF INTENT TO ENFORCE COPYRIGHTS RESTORED UNDER THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT. COPYRIGHT RESTORATION OF WORKS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT; LIST IDENTIFYING COPYRIGHTS RESTORED UNDER THE URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENTS ACT FOR WHICH NOTICES OF INTENT TO ENFORCE RESTORED COPYRIGHTS WERE FILED IN THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE. The following excerpt is taken from Volume 62, Number 163 of the Federal Register for Friday, August 22,1997 (p. 443424854) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: the work is from a country with which LIBRARY OF CONGRESS the United States did not have copyright I. Background relations at the time of the work's Copyright Off ice publication); and The Uruguay Round General (3) Has at least one author (or in the 37 CFR Chapter II Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the case of sound recordings, rightholder) Uruguay Round Agreements Act who was, at the time the work was [Docket No. RM 97-3A] (URAA) (Pub. L. 103-465; 108 Stat. 4809 created, a national or domiciliary of an Copyright Restoration of Works in (1994)) provide for the restoration of eligible country. If the work was Accordance With the Uruguay Round copyright in certain works that were in published, it must have been first Agreements Act; List Identifying the public domain in the United States. published in an eligible country and not Copyrights Restored Under the Under section 104.4 of title 17 of the published in the United States within 30 Uruguay Round Agreements Act for United States Code as provided by the days of first publication.