Brisbane, 20 May 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latest Financials

Page 1 CONTENTS - Acknowledgment of country and partnerships - President's Report - Treasurer's Report - Station Manager's Report - Year at a glance - The Stats - Financial Report - 2018 AGM Meeting Minutes Page 2 We would like to start my report with acknowledging the traditional owners of the land that we meet, the station resides, and that we broadcast from. We pay our respects to the Yugara and Turrbal people and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. Page 3 PRESIDENT'S REPORT Hi everyone and welcome to our AGM. As you will have been aware there have been huge changes at the Station and I would like to just take a few moments to put things into perspective. We have lived through what is probably the fastest changing dynamic the world has ever seen and the momentum is growing. When I grew up all we had was radio and we listened faithfully to all the programmes as there was only one Station – the BBC in England and the ABC here. I worked at the BBC in the 50s and we had the huge tapes that I recognised when I came to 4RHP about 12 years ago. My first training on a computer was in the mid 70s and that was at one of the first companies to use computers. All very strange to us. The machines were big and bulky and the computer had a whole room to itself. We slowly got used to that and when I opened my own business in the early 80s we had home computers and can you believe it a mobile phone that was huge. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

Changing Stations

1 CHANGING STATIONS FULL INDEX 100 Top Tunes 190 2GZ Junior Country Service Club 128 1029 Hot Tomato 170, 432 2HD 30, 81, 120–1, 162, 178, 182, 190, 192, 106.9 Hill FM 92, 428 247, 258, 295, 352, 364, 370, 378, 423 2HD Radio Players 213 2AD 163, 259, 425, 568 2KM 251, 323, 426, 431 2AY 127, 205, 423 2KO 30, 81, 90, 120, 132, 176, 227, 255, 264, 2BE 9, 169, 423 266, 342, 366, 424 2BH 92, 146, 177, 201, 425 2KY 18, 37, 54, 133, 135, 140, 154, 168, 189, 2BL 6, 203, 323, 345, 385 198–9, 216, 221, 224, 232, 238, 247, 250–1, 2BS 6, 302–3, 364, 426 267, 274, 291, 295, 297–8, 302, 311, 316, 345, 2CA 25, 29, 60, 87, 89, 129, 146, 197, 245, 277, 354–7, 359–65, 370, 378, 385, 390, 399, 401– 295, 358, 370, 377, 424 2, 406, 412, 423 2CA Night Owls’ Club 2KY Swing Club 250 2CBA FM 197, 198 2LM 257, 423 2CC 74, 87, 98, 197, 205, 237, 403, 427 2LT 302, 427 2CH 16, 19, 21, 24, 29, 59, 110, 122, 124, 130, 2MBS-FM 75 136, 141, 144, 150, 156–7, 163, 168, 176–7, 2MG 268, 317, 403, 426 182, 184–7, 189, 192, 195–8, 200, 236, 238, 2MO 259, 318, 424 247, 253, 260, 263–4, 270, 274, 277, 286, 288, 2MW 121, 239, 426 319, 327, 358, 389, 411, 424 2NM 170, 426 2CHY 96 2NZ 68, 425 2Day-FM 84, 85, 89, 94, 113, 193, 240–1, 243– 2NZ Dramatic Club 217 4, 278, 281, 403, 412–13, 428, 433–6 2OO 74, 428 2DU 136, 179, 403, 425 2PK 403, 426 2FC 291–2, 355, 385 2QN 76–7, 256, 425 2GB 9–10, 14, 18, 29, 30–2, 49–50, 55–7, 59, 2RE 259, 427 61, 68–9, 84, 87, 95, 102–3, 107–8, 110–12, 2RG 142, 158, 262, 425 114–15, 120–2, 124–7, 129, 133, 136, 139–41, 2SM 54, 79, 84–5, 103, 119, 124, -

Ocean TV Manual O32 Series

Ocean TV Ocean Series Antennas OCEAN TV Satellite Antennas Ocean Series O32 Installation and User Manual Version 1.3 www.oceantv.com.au OCEAN TV © Ocean 1 TV 2010 www.oceantv.com.au Ocean TV Ocean Series Antennas Ocean O32 Antenna Type Parabola Frequency Band Ku Band Operating Frequency 10.7GHz to 12.75GHz Dish Dimension 320mm Radome Dimension 350x360mm Antenna Weight 3.8kg Antenna Gain 31dBi Minimum EIRP 50dBW Polarization V/H or RHCP/LHCP Type of Stabilization 2-Axis Step Motor Elevation Range 5° to 90° Azimuth Range 400° Tracking Rate 50°/sec Temperate Range -20° to 70° Power 12~24VDC (20.4w at 12vdc) OCEAN TV 2 www.oceantv.com.au Ocean TV Ocean Series Antennas Antenna System Overview Antenna Ocean TV System Overview Setup 1 1 Television with SD Satellite Receiver Coaxial Control Cable SD Satellite Receiver 12-24v DC Televisions IDU Indoor Unit NOTE:. Further Installation Options are available in Appendix E Figure 1 –1 System Diagram OCEAN TV 3 www.oceantv.com.au Ocean TV Ocean Series Antennas Contents 1 Introduction Specification………………….………………………………………………………………. 4 Antenna System Overview……………………………………………………………….. 5 Direct Broadcast Satellite Overview………………………….………………………. 6 System Components……………………………………………………………………..… 7 2 Installation Unpacking the Unit………………………………..……………………...................... 9 Preparing for the installation…………………………………………………………. 10 Selecting the location………….………………………………………………….……… 11 Equipment and cable installation…………..…………………………………….…. 12 Setting the LNB Skew Angle (Manual Skew version only)…………………. 13 3 Operation Receiving Satellite TV Signals…………….………………………………………….. 15 Turning the System On/Off…………..………………..……………………………... 16 Changing Channels………………………….…………………...…..……………….…. 17 Watching TV…………………………………………………………..…………….…..…. 17 Switching between Satellites……………………………………………….…………. 17 Operating the IDU……………………………………….……………………………….. 18 Choosing the Correct Satellite to Track……………………...……………….... 19 4 Troubleshooting Simple Check……………………………………………..………………….……………. 21 Causes and Remedies……………………………….……..……………………...……. -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station May 2019 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Beyond Zero 9 Phil Ackman Current Affairs 19 National Features and Documentary Bluesbeat 9 Playback 19 Series 1 Cinemascape 9 Pop Heads Hour of Power 19 National Radio News 1 Concert Hour 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 20 Good Morning Country 1 Contact! 10 Primary Perspectives 20 The Wire 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Radio-Active 20 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Dads on the Air 10 Real World Gardener 20 CONTENT Definition Radio 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 Saturday Breakfast 21 Daily Interview 2 Diffusion 11 Service Voices 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Dirt Music 11 Spectrum 21 Inside Motorsport 2 Earth Matters 11 Spotlight 22 Jumping Jellybeans 3 Fair Comment 12 Stick Together 22 More Civil Societies 3 FiERCE 12 Subsequence 22 Overdrive News 3 Fine Music Live 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 22 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Global Village 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 4 Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Bohemian Beat 23 Regional Voices 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 14 The Breeze 23 Rural Livestock 4 Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Folk Show 23 Rural News 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Fourth Estate 24 RECENT EXTRAS Indij Hip Hop Show 14 The Phantom Dancer 24 New Shoots 5 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 24 The Good Life: Season 2 5 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 24 City Road 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 25 Marysville -

Reclink Annual Report 2017-18

, Annual Report 2017-18 Partners Our Mission Respond. Rebuild. Reconnect. We seek to give all participants the power of purpose. About Reclink Australia Reclink Australia is a not-for-profit organisation whose aim is to enhance the lives of people experiencing disadvantage or facing significant barriers to participation, through providing new and unique sports, specialist recreation and arts programs, and pathways to employment opportunities. We target some of the community’s most vulnerable and isolated people; at risk youth, those experiencing mental illness, people with a disability, the homeless, people tackling alcohol and other drug issues and social and economic hardship. As part of our unique hub and spoke network model, Reclink Australia has facilitated cooperative partnerships with a membership of more than 290 community, government and private organisations. Our member agencies are committed to encouraging our target population group, under-represented in mainstream sport and recreational programs, to take that step towards improved health and self-esteem, and use Reclink Australia’s activities as a means of engagement for hard to reach population groups. Contents Our Mission 3 State Reports 11 About Reclink Australia 3 AAA Play 20 Why We Exist 4 Reclink India 22 What We Do 5 Art Therapy 23 Delivering Evidence-based Programs 6 Events, Fundraising and Volunteers 24 Transformational Links, Training Our Activities 32 and Education 7 Our Members 34 Corporate Governance 7 Gratitude 36 Founder’s Message 8 Our National Footprint 38 Improving Lives and Reducing Crime 9 Reclink Australia Staff 39 Community Partners 10 Contact Us 39 Notice of 2017 Annual General Meeting The Annual General Meeting for Members 1. -

Brisbane Used to Be Called the Deep North

Radical Media in the Deep North: The origins of 4ZZZ-FM by Alan Knight PhD Brisbane used to be called the Deep North. It spoke of a place where time passed slowly in the summer heat, where rednecks ran the parliament and the press, blacks died from beatings and the police thought themselves above the law. Even though Brisbane is situated in the bottom southeast quarter of the great northern state of Queensland, it's sobriquet represented a state of mind. Queensland was described as a cultural backwater lacking bookshops, political pubs, radio and television network headquarters and the publishing centres where Australian intellectuals could be seen and heard. It was fashionable, then as now, for many in Sydney and Melbourne to dismiss Queenslanders as naive, if not malignant conservatives. Yet in 1975, Brisbane created Australia's most radical politics and music station, 4ZZZ-FM. It broadcasts to this day. How did it come about and why? The Bitter Fight Queensland has a long, yet often forgotten history of conflict between conservatives and radicals. In a huge, decentralised state, the march to democracy has been signposted by demands for free speech expressed through a diversified media. ZZZ is an offspring of these battles, which were in part fought out in the state's mainstream and underground media. The bitter fight began in earnest in 1891, when Queensland shearers went on strike over work contracts. The strikers produced a flurry of cartoons, articles and satirical poems, which were passed around their camp fires. They joined armed encampments, which were broken up only after the government called in the military. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

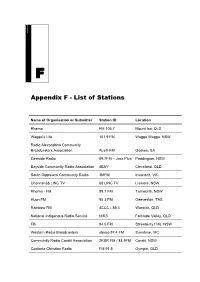

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1990-91 Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Sydney 1991 © Commonwealth of Australia ISSN 0728-8883 Design by Publications and Public Relations Branch, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. Printed in Australia by Pirie Printers Sales Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.CT. 11 CONTENTS 1. Membership of the Tribunal 1 2. The Year in Review 5 3. Powers and Functions of the Tribunal 11 Responsible Minister 14 4. Licensing 15 Number and Type of Licences on Issue 17 Number of Licensing Inquiries 19 Bond Inquiry 19 Commercial Radio Licence Grant Inquiries 20 Supplementary Radio Grant 21 Joined Supplementary /Independent Grant Inquiries 22 Remote Licences 22 Public Radio Licence Grants 23 Licence renewals 27 Renewal of Licences with Conditions 27 Revocation/ Suspension/ Conditions Inquiries 28 Revocation of Licence Conditions 31 Consolidation of Licences 32 Surrender of the 6CI Licence 33 Allocation of Call Signs 33 Changes to the Constituent Documents of Licensees 35 5. Ownership and Control 37 Applications Received 39 Most Significant Inquiries 39 Extensions of Time to Comply with the Act 48 Appointment of Receivers 48 Uncompleted Inquiries 49 Contraventions Amounting To Offences 51 Licence Transfers 52 Uncompleted Inquiries 52 Operation of Service by Other than Licensee 53 Registered Lender and Loan Interest Inquiries 53 6. Program and Advertising Standards 55 Program and Advertising Standards 57 Australian Content (Radio and Television) 58 Compliance with Australian Content Television Standards 60 Children's and Preschool Children's Television Standards 60 Compliance with Children's Television Standards 63 Comments and Complaints 64 Broadcasting of Political Matter 65 Research 66 Ill 7. -

The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia

NOVEMBER 2012 || The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia National Listener Survey Results || Radio With Pictures || Networking The News 8 10 contents President's Column ....................................................... 2 CBAA Update ............................................................... 3 National Listener Survey.............................................. 4 12 Project News ................................................................. 6 By Invitation ................................................................. 7 Networking the News ................................................... 8 Small Talk .................................................................. 10 Radio with Pictures .................................................... 12 Radio Days ................................................................. 15 Across the Sector ....................................................... 16 Station to Station ........................................................ 19 20 Making Radio ............................................................. 20 Getting the Message Across ....................................... 22 24 Out of the Box ............................................................ 24 2 The Magazine of the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia • November 2012 E CBAA H T M O Conference, R F S W IE CBX is the magazine of the D V Community Broadcasting Association an Codes, Campaigns, of Australia. W NES CBX is mailed to CBAA members and stakeholders. Subscribe -

Call Sign Station Name 1RPH Radio 1RPH 2AAA 2AAA 2ARM Armidale

Call Sign Station Name 1RPH Radio 1RPH 2AAA 2AAA 2ARM Armidale Community Radio - 2ARM FM92.1 2BBB 2BBB FM 2BLU RBM FM - 89.1 Radio Blue Mountains 2BOB 2BOB RADIO 2CBA Hope 103.2 2CCC Coast FM 96.3 2CCR Alive905 2CHY CHYFM 104.1 2DRY 2DRY FM 2EAR Eurobodalla Radio 107.5 2GCR FM 103.3 2GLA Great Lakes FM 2GLF 89.3 FM 2GLF 2HAY 2HAY FM 92.1 Cobar Community Radio Incorporated 2HOT FM 2KRR KRR 98.7 2LVR 97.9 Valley FM 2MBS Fine Music 102.5 2MCE 2MCE 2MIA The Local One 95.1 FM 2MWM Radio Northern Beaches 2NBC 2NBC 90.1FM 2NCR River FM - 92.9 2NSB FM 99.3 - 2NSB 2NUR 2NURFM 103.7 2NVR Nambucca Valley Radio 2OCB Orange FM 107.5 2OOO 2TripleO FM 2RDJ 2RDJ FM 2REM 2REM 107.3FM 2RES 89.7 Eastside Radio 2RPH 2RPH - Sydney's Radio Reading Service 2RRR 2RRR 2RSR Radio Skid Row 2SER 2SER 2SSR 2SSR 99.7 FM 2TEN TEN FM TLC 100.3FM TLC 100.3 FM 2UUU Triple U FM 2VOX VOX FM 2VTR Hawkesbury Radio 2WAY 2WAY 103.9 FM 2WEB Outback Radio 2WEB 2WKT Highland FM 107.1 1XXR 2 Double X 2YOU 88.9 FM 3BBB 99.9 Voice FM 3BGR Good News Radio 3CR 3CR 3ECB Radio Eastern FM 98.1 3GCR Gippsland FM 3GRR Radio EMFM 3HCR 3HCR - High Country Radio 3HOT HOT FM 3INR 96.5 Inner FM 3MBR 3MBR FM Mallee Border Radio 3MBS 3MBS 3MCR Radio Mansfield 3MDR 3MDR 3MFM 3MFM South Gippsland 3MGB 3MGB 3MPH Vision Australia Radio Mildura 107.5 3NOW North West FM 3ONE OneFM 98.5 3PBS PBS - 3PBS 3PVR Plenty Valley FM 88.6 3REG REG-FM 3RIM 979 FM 3RPC 3RPC FM 3RPH Vision Australia 3RPH 3RPP RPP FM 3RRR Triple R (3RRR) 3SCB 88.3 Southern FM 3SER Casey Radio 3UGE UGFM - Radio Murrindindi 3VYV Yarra -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station January 2020 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Chimes 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 19 National Features and Documentary Cinemascape 9 Primary Perspectives 20 Series 1 Concert Hour 10 Radio-Active 20 National Radio News 1 Contact! 10 Real World Gardener 20 Good Morning Country 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 20 The Wire 1 Dads on the Air 10 Saturday Breakfast 21 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Deadly Beats 11 Service Voices 21 CONTENT Definition Radio 11 Spectrum 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 SPORTSLINE 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Diffusion 11 Spotlight 22 Inside Motorsport 2 Dirt Music 12 Stick Together 23 More Civil Societies 2 Earth Matters 12 Subsequence 23 Overdrive News 3 Fair Comment 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 23 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Fierce 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 3 Fine Music Live 13 The Bohemian Beat 24 Rural News | Rural Livestock 3 Global Village 13 The Breeze 24 RECENT EXTRAS Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Cut 24 Little Fictions 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 13 The Folk Show 24 Baby Boomers’ Guide to Life in the 21st Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Fourth Estate 25 Century 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Phantom Dancer 25 No Land, No Livelihood, No Home 4 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 25 Live In The Room 4 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 25 New Beginnings 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 26 Beyond The Bars 5 Jazz Made in Australia