Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulmonary Manifestations of Left Heart Failure*

The Pulmonary Manifestations of Left Heart Failure* Brian K. Gehlbach, MD; and Eugene Geppert, MD Determining whether a patient’s symptoms are the result of heart or lung disease requires an understanding of the influence of pulmonary venous hypertension on lung function. Herein, we describe the effects of acute and chronic elevations of pulmonary venous pressure on the mechanical and gas-exchanging properties of the lung. The mechanisms responsible for various symptoms of congestive heart failure are described, and the significance of sleep-disordered breathing in patients with heart disease is considered. While the initial clinical evaluation of patients with dyspnea is imprecise, measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide levels may prove useful in this setting. (CHEST 2004; 125:669–682) Key words: Cheyne-Stokes respiration; congestive heart failure; differential diagnosis; dyspnea; pulmonary edema; respiratory function tests; sleep apnea syndromes Abbreviations: CHF ϭ congestive heart failure; CSR-CSA ϭ Cheyne-Stokes respiration with central sleep apnea; CPAP ϭ continuous positive airway pressure; Dlco ϭ diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; DM ϭ membrane conductance; FRC ϭ functional residual capacity; OSA ϭ obstructive sleep apnea; TLC ϭ total lung ϭ ˙ ˙ ϭ capacity; VC capillary volume; Ve/Vco2 ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide early 5 million Americans have congestive heart For a detailed review of the pathophysiology of N failure (CHF), with 400,000 new cases diag- high-pressure pulmonary edema, the reader is re- nosed each year.1 Unfortunately, despite the consid- ferred to several excellent recent reviews.2–4 erable progress that has been made in understanding the pathophysiology of pulmonary edema, the pul- monary complications of this condition continue to The Pathophysiology of Pulmonary challenge the bedside clinician. -

Percutaneous Mitral Valve Therapies: State of the Art in 2020 LA ACP Annual Meeting

Percutaneous Mitral Valve Therapies: State of the Art in 2020 LA ACP Annual Meeting Steven R Bailey MD MSCAI, FACC, FAHA,FACP Professor and Chair, Department of Medicine Malcolm Feist Chair of Interventional Cardiology LSU Health Shreveport Professor Emeritus, UH Health San Antonio [email protected] SRB March 2020 Disclosure Statement of Financial Interest Within the past 12 months, I or my spouse/partner have had a financial interest/arrangement or affiliation with the organization(s) listed below. Affiliation/Financial Relationship Company • Grant/Research Support • None • Consulting Fees/Honoraria • BSCI, Abbot DSMB • Intellectual Property Rights • UTHSCSA • Other Financial Benefit • CCI Editor In Chief SRB March 2020 The 30,000 Ft View Maria SRB March 2020 SRB March 2020 Mitral Stenosis • The most common etiology of MS is rheumatic fever, with a latency of approximately 10 to 20 years after the initial streptococcal infection. Symptoms usually appear in adulthood • Other etiologies are rare but include: congenital MS radiation exposure atrial myxoma mucopolysaccharidoses • MS secondary to calcific annular disease is increasingly seen in elderly patients, and in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. SRB March 2020 Mitral Stenosis • Mitral stenosis most commonly results from rheumatic heart disease fusion of the valve leaflet cusps at the commissures thickening and shortening of the chordae calcium deposition within the valve leaflets • Characteristic “fish-mouth” or “hockey stick” appearance on the echocardiogram (depending on view) SRB March 2020 Mitral Stenosis: Natural History • The severity of symptoms depends primarily on the degree of stenosis. • Symptoms often go unrecognized by patient and physician until significant shortness of breath, hemoptysis, or atrial fibrillation develops. -

Currentstateofknowledgeonaetiol

European Heart Journal (2013) 34, 2636–2648 ESC REPORT doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht210 Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases Downloaded from Alida L. P. Caforio1†*, Sabine Pankuweit2†, Eloisa Arbustini3, Cristina Basso4, Juan Gimeno-Blanes5,StephanB.Felix6,MichaelFu7,TiinaHelio¨ 8, Stephane Heymans9, http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ Roland Jahns10,KarinKlingel11, Ales Linhart12, Bernhard Maisch2, William McKenna13, Jens Mogensen14, Yigal M. Pinto15,ArsenRistic16, Heinz-Peter Schultheiss17, Hubert Seggewiss18, Luigi Tavazzi19,GaetanoThiene4,AliYilmaz20, Philippe Charron21,andPerryM.Elliott13 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Cardiological Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy; 2Universita¨tsklinikum Gießen und Marburg GmbH, Standort Marburg, Klinik fu¨r Kardiologie, Marburg, Germany; 3Academic Hospital IRCCS Foundation Policlinico, San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 4Cardiovascular Pathology, Department of Cardiological Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy; 5Servicio de Cardiologia, Hospital U. Virgen de Arrixaca Ctra. Murcia-Cartagena s/n, El Palmar, Spain; 6Medizinische Klinik B, University of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; 7Department of Medicine, Heart Failure Unit, Sahlgrenska Hospital, University of Go¨teborg, Go¨teborg, Sweden; 8Division of Cardiology, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Heart & Lung Centre, -

Heart Failure

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Heart Failure What is it? Enlarged heart Heart failure is a condition in which your heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Usually, this is because your heart muscle is too weak to “squeeze” out enough blood with each beat. But heart failure can also happen when your heart gets stiff “Normal” heart and can’t fill up with enough blood between each beat. Heart failure is found most often in older people, but it can happen to anyone at any age. It’s a serious condition — and also quite common. Many people with heart failure continue to have a full and active life for many years after their diagnosis. What are the symptoms? Symptoms of heart failure vary based on the type of With heart failure, initial damage weakens the heart failure you have. Common symptoms include: heart muscle. This makes your heart beat faster, and the muscle stretches or thickens. Over time, • Shortness of breath the heart muscle begins to wear out. • Cough • Feeling very tired and weak • Atherosclerosis (coronary artery disease). • Weight gain (from fluid buildup) Atherosclerosis is when the arteries that supply your • Swollen ankles, feet, belly, lower back, and fingers heart with blood become narrowed by fatty plaque • Puffiness or swelling around the eyes buildup. This restricts the amount of oxygen your • Trouble concentrating or remembering heart gets and weakens the muscle. It can also cause a heart attack, which can damage your heart even more. The main cause of heart failure (heart muscle damage and weakness) cannot be cured, but symptoms can be • High blood pressure (hypertension). -

Heart Disease and Diseases of the Circulatory System in Westchester

Westchester County 2016.01 Department of Health KEEP HEALTHY @wchealthdept AND Community Health Assessment Data Update GET #keephealthy THE STATS Heart Disease and Diseases of the Circulatory System in Westchester In this issue: Heart disease as a Heart disease is the number one cause of death in Westchester County. leading cause of death in Westchester county In 2012, heart disease accounted for 2,113 deaths or 31% of all deaths Deaths due to heart disease across different in the county. Adding in 490 deaths due to stroke and other diseases population and risk of the circulatory system, total deaths from circulatory disease are groups 60% higher than the next leading cause of death - cancer. Hospitalizations due to cardiovascular disease- related conditions, Selected Causes of Death in Westchester County, 2012 including diseases of the heart Emergency room visits 2% 3% 7% due to cardiovascular disease-related 3% conditions Selected risk factors 4% that contribute to Heart Disease, cardiovascular disease 4% in Westchester county 31% 5% 9% Cerebrovascular Jiali Li, Ph.D. Director of Disease (Stroke), Research & Evaluation Neoplasms 5% Planning & Evaluation (Cancer), 24% Other Circulatory, Renee Recchia, MPH 3% Acting Deputy Commissioner of Administration Heart Disease Cerebrovascular Disease (Stroke) Project Staff: Other Circulatory Neoplasms (Cancer) Bonnie Lam, MPH Respiratory Diseases External Causes (e.g. accidents) Medical Data Analyst Communicable Diseases Nervous System Diseases Milagros Venuti, MPA Digestive System Diseases -

Cardiovascular Disease: a Costly Burden for America. Projections

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE: A COSTLY BURDEN FOR AMERICA PROJECTIONS THROUGH 2035 CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE: A COSTLY BURDEN FOR AMERICA — PROJECTIONS THROUGH 2035 american heart association CVD Burden Report CVD Burden association heart american table of contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................5 ABOUT THIS STUDY ................................................................................................... 6 WHAT IS CVD? ......................................................................................................... 6 Atrial Fibrillation Congestive Heart Failure Coronary Heart Disease High Blood Pressure Stroke PROJECTIONS: PREVALENCE OF CVD .............................................................7 Latest Projections Age, Race, Sex – Differences That Matter PROJECTIONS: COSTS OF CVD ................................................................. 8-11 The Cost Generators: Aging Baby Boomers Medical Costs Breakdown Direct Costs + Indirect Costs RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................13-14 Research Prevention Affordable Health Care 3 CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE: A COSTLY BURDEN FOR AMERICA — PROJECTIONS THROUGH 2035 american heart association CVD Burden Report CVD Burden association heart american Introduction Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been the leading killer In addition, CVD has become our nation’s costliest chronic of Americans for decades. In years past, a heart attack disease. In 2014, stroke and heart -

Heart3-Congestive Heart Failure

HEART DISEASE Congestive Heart Failure What is congestive heart failure? Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) is a term that refers to the heart’s inability to pump adequate blood to the body. There are many causes of CHF in dogs. The two most common causes are mitral valve insufficiency (MVI) and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Clinical signs vary depending on whether the dog has left- or right-sided heart failure. The most common symptoms are decreased stamina, coughing or difficulty breathing. What is the difference in the signs? Right-sided congestive heart failure causes poor venous return to the heart. In other words, when the heart contracts instead of the right ventricle pushing the blood through the lungs for oxygenation, some returns to the right auricle. This blood is unable to be cleared from the systemic circulation and consequently becomes “congested”. Fluid accumulates in the abdomen and/or the chest cavity, interfering with the function of the organs in these areas. The abdomen may become enlarged with fluid called ascites. Fluid may also leak from veins and swelling may appear in the limbs (peripheral edema). When CHF involves the left ventricle, blood is not pumped into the systemic circulation and builds up in the lungs. Fluid then seeps into the lung tissue resulting in pulmonary edema. This causes coughing and difficulty breathing. Is CHF due mainly to heart valve disease? CHF is most commonly caused by valvular insufficiency. It is estimated that 80% of the canine CHF cases are caused by MVI. However, there are many other causes. Disease of the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy), irregularities of rhythm and narrowing of some of the major blood vessels can also cause CHF. -

Inflammation and Your Heart: Endocarditis, Pericarditis and Myocarditis

Inflammation and your heart: Endocarditis, pericarditis and myocarditis Types of inflammation Myocarditis When you see the letters ‘itis’ at the end of a What causes myocarditis? Will I need treatment? word, it means inflammation. Myocarditis is inflammation of the myocardium Myocarditis is often mild and goes unnoticed, but – the heart muscle. It is usually caused by a viral, you may need to take medicines to relieve your Myocarditis, pericarditis and bacterial or fungal infection. Sometimes the cause is symptoms such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories endocarditis refer to inflammation unknown – or ‘idiopathic’. and sometimes antibiotics. around or in the heart. If the myocarditis it is causing a problem with What are the symptoms? how well your heart pumps, you may develop the • Myocarditis – inflammation of the myocardium The symptoms of myocarditis usually include a (the heart muscle) symptoms of heart failure which you will need to pain or tightness in your chest which can spread to take several different types of medicines for. In very • Pericarditis – inflammation of the pericardium other parts of your body, shortness of breath and extreme cases where there is severe damage to the (the sac which surrounds tiredness. You may also have flu like symptoms, such heart you may be considered for a heart transplant. the heart) as a high temperature, feeling tired, headaches and aching muscles and joints. • Endocarditis – inflammation of the Inflammation of the heart often causes chest pain, endocardium (the inner lining of the heart) What tests will I need? and you may feel like you are having a heart attack. If you have not been diagnosed with one of You may need to have an electrocardiogram (ECG), these conditions and you have chest pain, or any echocardiogram (a scan of your heart similar to an of the symptoms we describe below, call 999 ultrasound) and various blood tests. -

Cardiomyopathy- the Facts

Cardiomyopathy- the facts What is it? Cardiomyopathy means disease of the heart muscle. Different types of cardiomyopathy? If you have cardiomyopathy it may mean that your • Dilated cardiomyopathy heart muscle has become enlarged, thicker or stiff. • Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy If this happens your heart is less able to pump blood • Restrictive cardiomyopathy through your body and you may get abnormal heart • Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) rhythms. This can lead to heart failure or arrhythmia. In turn, heart failure can cause fluid to build up You can get cardiomyopathy at any age, however if in the lungs, ankles, feet, legs, or abdomen. The you have Barth syndrome you are most likely to get weakening of the heart can also cause other severe this as a baby. Although you can get different types of complications, such as heart valve problems. cardiomyopathy if you have Barth Syndrome the most common type is dilated cardiomyopathy. Tell me more about dilated cardiomyopathy? Having dilated cardiomyopathy means that the left ventricle becomes dilated (stretched). When this happens, the heart muscle becomes weak and thin and is unable to pump blood efficiently around the body. This can lead to fluid building up in the lungs and a feeling of being breathless. This collection of symptoms is known as heart failure. Dilated cardiomyopathy develops slowly, so most people have quite severe symptoms before they are diagnosed. There may also be ‘mitral regurgitation’. This is when some of the blood flows in the wrong direction through the mitral valve, from the left ventricle to the left atrium. How do you get it? What about the future? Cardiomyopathy can be acquired or inherited. -

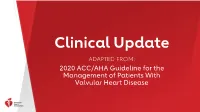

Valvular Heart Disease CLASS (STRENGTH) of RECOMMENDATION LEVEL (QUALITY) of EVIDENCE‡ CLASS 1 (STRONG) Benefit >>> Risk LEVEL A

Clinical Update ADAPTED FROM: 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease CLASS (STRENGTH) OF RECOMMENDATION LEVEL (QUALITY) OF EVIDENCE‡ CLASS 1 (STRONG) Benefit >>> Risk LEVEL A Suggested phrases for writing recommendations: • High-quality evidence‡ from more than 1 RCT • Is recommended • Meta-analyses of high-quality RCTs • Is indicated/useful/effective/beneficial • One or more RCTs corroborated by high-quality registry studies • Should be performed/administered/other Table 1. • Comparative-Effectiveness Phrases†: LEVEL B-R (Randomized) − Treatment/strategy A is recommended/indicated in preference to • Moderate-quality evidence‡ from 1 or more RCTs treatment B ACC/AHA • Meta-analyses of moderate-quality RCTs − Treatment A should be chosen over treatment B LEVEL B-NR (Nonrandomized) Applying Class of CLASS 2a (MODERATE) Benefit >> Risk • Moderate-quality evidence‡ from 1 or more well-designed, well- Suggested phrases for writing recommendations: executed nonrandomized studies, observational studies, or registry Recommendation Is reasonable • studies • Can be useful/effective/beneficial • Meta-analyses of such studies and Level of • Comparative-Effectiveness Phrases†: − Treatment/strategy A is probably recommended/indicated in preference to LEVEL C-LD (Limited Data) treatment B Evidence to − It is reasonable to choose treatment A over treatment B • Randomized or nonrandomized observational or registry studies with limitations of design or execution Clinical Strategies, CLASS 2b (Weak) Benefit ≥ Risk • Meta-analyses of such studies • Physiological or mechanistic studies in human subjects Suggested phrases for writing recommendations: Interventions, • May/might be reasonable LEVEL C-EO (Expert Opinion) • May/might be considered Treatments, or • Usefulness/effectiveness is unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established • Consensus of expert opinion based on clinical experience. -

The Dynamics of Congestive Heart Failure

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1938 The Dynamics of congestive heart failure Marvin I. Pizer University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Pizer, Marvin I., "The Dynamics of congestive heart failure" (1938). MD Theses. 691. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/691 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DYNAMICS OF CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE BY MARVIN I. 1 IZER *** SENIOR THESIS PRESDTED TO THE OOI.LEGE OF MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASD. OMAHA, 1938 TABLE OF CONTENTS ** Page Introduction••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• l History•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 Definition of Terms•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 19 Mechanism of Adaptation to Venous Return, Arterial Pressure, and Heart Rate....... 22 Summary of Consecutive Events in Both Ventricles Following an Increased Venous Return, Arterial Resistance, and Cardiac Slowing••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Theories of The Dynamics of Congestive Heart Failure••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 37 The "Forward-Failure" Hypothesis of -Inadequate Cardiac -

ICD-10: Clinical Concepts for Cardiology

ICD-10 Clinical Concepts for Cardiology ICD-10 Clinical Concepts Series Common Codes Clinical Documentation Tips Clinical Scenarios ICD-10 Clinical Concepts for Cardiology is a feature of Road to 10, a CMS online tool built with physician input. With Road to 10, you can: l Build an ICD-10 action plan customized l Access quick references from CMS and for your practice medical and trade associations l Use interactive case studies to see how l View in-depth webcasts for and by your coding selections compare with your medical professionals peers’ coding To get on the Road to 10 and find out more about ICD-10, visit: cms.gov/ICD10 roadto10.org ICD-10 Compliance Date: October 1, 2015 Official CMS Industry Resources for the ICD-10 Transition www.cms.gov/ICD10 1 Table Of Contents Common Codes • Abnormalities of • Hypertension Heart Rhythm • Nonrheumatic • Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter Valve Disorders • Cardiac Arrhythmias (Other) • Selected Atherosclerosis, • Chest Pain Ischemia, and Infarction • Heart Failure • Syncope and Collapse Clinical Documentation Tips • Acute Myocardial • Atheroclerotic Heart Disease Infraction (AMI) with Angina Pectoris • Hypertension • Cardiomyopathy • Congestive Heart Failure • Heart Valve Disease • Underdosing • Arrythmias/Dysrhythmia Clinical Scenarios • Scenario 1: Hypertension/ • Scenario 4: Subsequent AMI Cardiac Clearance • Scenario: CHF and • Scenario 2: Syncope Pulmonary Embolism Example • Scenario 3: Chest Pain Common Codes ICD-10 Compliance Date: October 1, 2015 Abnormalities of Heart Rhythm (ICD-9-CM 427.81, 427.89, 785.0, 785.1, 785.3) R00.0 Tachycardia, unspecified R00.1 Bradycardia, unspecified R00.2 Palpitations R00.8 Other abnormalities of heart beat R00.9* Unspecified abnormalities of heart beat *Codes with a greater degree of specificity should be considered first.