Habitat Action Plan 'Woodlands' Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Setting Appraisal

LT09 Shetland-Caithness HVDC Cable Sound Scheduled Monument, Weisdale Voe, Shetland Setting Appraisal Side scan: HMS Bow, SS Ilsenstein Roedean Project No: 855 ORCA UHI Archaeology Institute Orkney College UHI East Road Kirkwall KW15 1LX Project Manager: Pete Higgins Report Author: Paul Sharman Report Figures: SSE, Crane Begg, Samantha Dennis Client: Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks This document has been prepared in accordance with ORCA standard operating procedures and CIfA standards Authorised for Distribution by: Pete Higgins Date: 26nd May 2020 1 2 Title: Sound Scheduled Monument, Weisdale Voe, Shetland: Setting Appraisal Author(s): Paul Sharman Editor Paul Sharman & Pete Higgins Origination Request from SSE 10th May 2020 Date: Reviser(s): Pete Higgins Date of last 26nd May 2020 revision: Version: Final Status: Final Circulation: ORCA and SSE (Mairi Rigby) Required Comment and feedback or acceptance Action: File Name / \\oc-f02\archaeologyall\ORCA\ORCA Location: Projects\SHETLAND\1203\Setting\Sound SM Setting v2.doc Approval: [Redacted] 3 Sound SM Setting Appraisal Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................... 5 2.0 Legislative Framework and Policy Context ....................................... 5 2.1 International and European .......................................................... 6 2.2 UK and Scottish Legislation .......................................................... 6 2.3 Scottish Policy and Guidance ...................................................... -

The Shetland Islands David Crichton1, Chartered Insurance Practitioner ______

© Crichton 2003 1 The Shetland Islands David Crichton1, Chartered Insurance Practitioner _________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Victor Hawthorne of Shetland Islands Council, Department of Infrastructure Services for his invaluable assistance. He also wishes to thank Dr Derek Mcglashan at the University of Dundee for his advice on udal law, Dr Olivia Bragg at the University of Dundee for her advice on peat slides, and Professor Alistair Dawson at Coventry University for information on historic storms. In addition, he would also like to thank Dr David Cameron and David Okill of the Scottish Environment Protection Agency for their comments on the draft of this paper. Note This paper was issued in July 2003 and a copy given to Shetland Islands Council. Please note this is an edited version which omits details of certain specific areas of concern. Funding This research was made possible by funding from esure insurance services Ltd. Abstract Shetland is one of the stormiest places in Europe. The islands are very exposed to westerly gales from the North Atlantic and over the years the population has learned to ensure that the buildings are constructed to high standards of resilience. As a result, wind damage is rare and minor even in the strongest storms. The islands are therefore a good example of how resilient design and construction can reduce vulnerability to such an extent that the risk is minimised even in areas exposed to severe hazards. Key words: Shetland, storm, vulnerability, flood, climate change, insurance. Introduction The Shetland Islands, or Shetland2 is a group of islands, located 200km to the North of the British mainland. -

Orkney & Shetland

r’ Soil Survey of Scotland ORKNEY & SHETLAND 1250 000 SHEET I The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 SOIL SURVEY OF SCOTLAND Soil and Land Capability for Agriculture ORKNEY AND SHETLAND By F. T. Dry, BSc and J. S. Robertson, BSc The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 @ The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen, 1982 The cover illustration shows St. Magnus Bay, Shetland with Foula (centre nght) in the distance. Institute of Geological Sciences photograph published by permission of the Director; NERC copyright. ISBN 0 7084 0219 4 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS ABERDEEN Contents Chapter Page PREFACE 1 DESCRIPTIONOF THE AREA 1 GEOLOGY AND RELIEF 1 North-east Caithness and Orkney 1 Shetland 3 CLIMATE 9, SOILS 12 North-east Caithness and Orkney 12 Shetland 13 VEGETATION 14 North-east Caithness and Orkney 14 Shetland 16 LAND USE 19 North-east Caithness and Orkney 19 Shetland 20 2 THE SOIL MAP UNITS 21 Alluvial soils 21 Organic soils 22 The Arkaig Association 24 The Canisbay Association 29 The Countesswells/Dalbeattie/Priestlaw Associations 31 The Darleith/Kirktonmoor Associations 34 The Deecastle Association 35 The Dunnet Association 36 The Durnhill Association 38 The Foudland Association 39 The Fraserburgh Association 40 The Insch Association 41 The Leslie Association 43 The Links Association 46 The Lynedardy Association 47 The Rackwick Association 48 The Skelberry Association 48 ... 111 CONTENTS The Sourhope Association 50 The Strichen Association 50 The Thurso Association 52 The Walls -

Central Mainland the Heart of Shetland Research Facilities for Scientific and Technological Projects Relating to the Fishing and Aquaculture Industries

Central Scalloway’s Westshore Public art on New Street Mainland Out at Port Arthur the marina and Scalloway Boating Club offer a safe haven and a warm welcome for visiting boats and their crews. Next to the boating club is the NAFC Marine Centre, the Centre offers training in nautical studies and Central Mainland The heart of Shetland research facilities for scientific and technological projects relating to the fishing and aquaculture industries. It also houses an excellent fish restaurant. Traditional boats drawn up on shore recall Shetland’s Some Useful Information fishing past. In Norse times Scalloway (‘the bay of the Accommodation: VisitShetland hall’) may have been the home of an important landowner Tel: 08701 999440 or official. Airport (inter-island): Tingwall Tel: (01595) 840246 Scalloway’s other attractions include a heated 17-metre Neighbourhood Scalloway Post Office indoor swimming pool, the youth centre, a hotel, guest Information Point Shetland Jewellry, Weisdale houses, cafes, pubs, shops and playing fields. Shops: Hamnavoe; Scalloway; Throughout the village are a number of works of public Whiteness; Weisdale art including sculptures done in Hildasay granite and Petrol: Burra; Weisdale flower tubs recycled from tractor wheels and tyres. Public toilets: Hamnavoe; Meal Beach; Scalloway Pubs and places to eat: Scalloway; Tingwall; Whiteness; Weisdale Post Offices: Hamnavoe; Weisdale; Scalloway Public telephones: Scalloway; Burra; Tingwall; Whiteness; Weisdale Museums and The NAFC Marine Centre overlooks the entrance to Scalloway Harbour Heritage Centres Scalloway, Burra Swimming pool: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880745 Churches: Burra; Scalloway; Whiteness; Weisdale; Girlsta; Tingwall Doctor and Health Centre: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880219 Police Station: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880222 Contents copyright protected – please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. -

Scottish Sanitary Survey Report

Scottish Sanitary Survey Report yyy Sanitary Survey Report East Burwick SI-583-1060-08 October 2014 East Burwick Sanitary Report Title Survey Report Scottish Sanitary Survey Project Name Programme Food Standards Agency in Client/Customer Scotland Cefas Project Reference C6316C Document Number C6316C_2014_7 Revision V1.0 Date 27/10/2014 Revision History Revision Date Pages revised Reason for revision number 0.1 05/09/2014 - Draft report for consultation Correction of typographical 1.0 27/10/2014 1, 27 errors noted in consultation Name Position Date Jessica Larkham, Frank Scottish Sanitary Author Cox, Liefy Hendrikz, 27/10/2014 Survey Team Michelle Price-Hayward Principal Shellfish Checked Ron Lee 28/10/2014 Hygiene Scientist Principal Shellfish Approved Ron Lee 28/10/2014 Hygiene Scientist This report was produced by Cefas for its Customer, FSAS, for the specific purpose of providing a sanitary survey as per the Customer’s requirements. Although every effort has been made to ensure the information contained herein is as complete as possible, there may be additional information that was either not available or not discovered during the survey. Cefas accepts no liability for any costs, liabilities or losses arising as a result of the use of or reliance upon the contents of this report by any person other than its Customer. Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Weymouth Laboratory, Barrack Road, The Nothe, Weymouth DT4 8UB. Tel 01305 206 600 www.cefas.defra.gov.uk East Burwick Sanitary Survey Report V1.0 27/10/2014 Page i of 120 Report Distribution – East Burwick Date Name Agency Joyce Carr Scottish Government David Denoon SEPA Douglas Sinclair SEPA Hazel MacLeod SEPA Fiona Garner Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Dawn Manson Local Authority Sean Williamson HMMH (Scotland) Ltd Michael Tait Harvester Partner Organisations The hydrographic assessment and the shoreline survey and its associated report were undertaken by Shetland Seafood Quality Control, Scalloway. -

The Laird's Houses of Scotland

The Laird’s Houses of Scotland: From the Reformation to the Industrial Revolution, 1560–1770 Sabina Ross Strachan PhD by Research The University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis has been composed by me, the work is my own, and it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except for this degree of PhD by Research. Signed: ............................................................................ Date:................................... Sabina Ross Strachan Contents List of Figures ix List of Tables xvii Abstract xix Acknowledgements xxi List of Abbreviations xxiii Part I 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Context 3 1.2.1 The study of laird’s houses 3 1.2.2 High-status architecture in early modern Scotland 9 1.3 ‘The Laird’s Houses of Scotland’: aims 13 1.4 ‘The Laird’s Houses of Scotland’: scope and structure 17 1.4.1 Scope 17 1.4.2 Structure 19 1.5 Conclusion 22 Chapter 2 Literature Review 25 2.1 Introduction 25 2.2 An overview of laird’s houses 26 2.2.1 Dunbar, The Historic Architecture of Scotland, 1966 26 2.2.2 General surveys: MacGibbon & Ross (1887–92) and Tranter (1962) 28 2.2.3 Later commentators: 1992–2003 30 2.3 Regional, group and individual studies on laird’s houses 32 2.3.1 Regional surveys 32 2.3.2 Group studies 35 2.3.3 Individual studies 38 2.4 Conclusion 40 Chapter 3 Methodology 43 3.1 Introduction 43 3.2 Scope and general methodology 43 3.3 Defining the ‘laird’s house’ 47 3.3.1 What is a ‘laird’? 48 3.3.2 What is a ‘laird’s house’? -

Orkney and Shetland

Orkney and Shetland: A Landscape Fashioned by Geology Orkney and Shetland Orkney and Shetland are the most northerly British remnants of a mountain range that once soared to Himalayan heights. These Caledonian mountains were formed when continents collided around A Landscape Fashioned by Geology 420 million years old. Alan McKirdy Whilst the bulk of the land comprising the Orkney Islands is relatively low-lying, there are spectacular coastlines to enjoy; the highlight of which is the magnificent 137m high Old Man of Hoy. Many of the coastal cliffs are carved in vivid red sandstones – the Old Red Sandstone. The material is also widely used as a building stone and has shaped the character of the islands’ many settlements. The 12th Century St. Magnus Cathedral is a particularly fine example of how this local stone has been used. OrKney A Shetland is built largely from the eroded stumps of the Caledonian Mountains. This ancient basement is pock-marked with granites and related rocks that were generated as the continents collided. The islands of the Shetland archipelago are also fringed by spectacular coastal features, nd such as rock arches, plunging cliffs and unspoilt beaches. The geology of Muckle Flugga and the ShetLAnd: A LA Holes of Scraada are amongst the delights geologists and tourists alike can enjoy. About the author Alan McKirdy has worked in conservation for over thirty years. He has played a variety of roles during that period; latterly as Head of Information Management at SNH. Alan has edited the Landscape nd Fashioned by Geology series since its inception and anticipates the completion of this 20 title series ScA shortly. -

Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll a Poll Will Be Held on 12 December 2019 Between 07:00 and 22:00

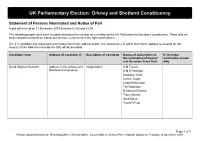

UK Parliamentary Election: Orkney and Shetland Constituency Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll A poll will be held on 12 December 2019 between 07:00 and 22:00. The following people have been or stand nominated for election as a member of the UK Parliament for the above constituency. Those who no longer stand nominated are listed, but will have a comment in the right hand column. (i) = If a candidate has requested not to make their home address public, the constituency in which their home address is situated (or the country if their address is outside the UK) will be provided. Candidate name Address of candidate (i) Description of candidate Names of subscribers to If no longer the nomination (Proposer nominated, reason and Seconder listed first) why David Stephen Barnard. Address in the Orkney and Independent. S M Tyzack. Shetland Constituency. S M S Pottinger. Georgina Clark. Corina Taylor. Lindzi Williamson. Tim Robinson. R Kathryn Beharie. Tracy Sinclair. Ilona Borys. Yvonne Ford. Page 1 of 7 Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Election Office, Council Offices, School Place, Kirkwall, Orkney on Thursday 14 November 2019. Candidate name Address of candidate (i) Description of candidate Names of subscribers to If no longer the nomination (Proposer nominated, reason and Seconder listed first) why Alistair Carmichael. Old Manse, Evie, Orkney, Scottish Liberal Liam McArthur. KW17 2PH. Democrats. Beatrice Wishart. David Dawson. Alistair J Bruce. Dennis Gowland. Jane E Nelson. Brenda Wilcock. Theo Smith. Stephen A Leask. Ruth Williams. Coilla Anne Drake. Cott, Westray, Orkney, Scottish Labour Party. Ruth Ellen Millar. -

Enumeration of the Inhabitants of Scotland, Taken from The

• LIBRARY Author: [cLELAMD ( James) 1 770-1840] Title: Enumeration of the inhabitants of Scotland, • Acc. No. Class Mark Date Volume 86142 •x-EHP 1823 ENUMERATION OF THE INHABITANTS OF SCOTLAND, ENUMERATION OF THE INHABITANTS OF SCOTLAND, TAKEN FROM THE GOVERNMENT ABSTRACTS OF 1801, 1811, 1821; CONTAINING A PARTICULAR ACCOUNT OF EVERY PARISH IN SCOTLAND, AND MANY USEFUL DETAILS RESPECTING ENGLAND, WALES AND IRELAND. " An active and industrious population is the stay and support of every well governed " community." CoUfUhoun, GLASGOW: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LUMSDEN & SON, WAUGH & INNES, EDINBURGH, AND G. & W. B. WHITAKER, LONDON. 1823. TO JOHN RICKMAN, Esq. OF COMMONS, ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL CLERKS OF THE HOUSE AND THE DISTINGUISHED OFFICER WHOM COUNCIL HIS MAJESTY'S MOST HONOURABLE PRIVY CHARGED WITH THE IMPORTANT DUTY OF DIGESTING THE GOVERNMENT ENUMERATIONS OF THIS COUNTRY, THIS ABSTRACT OF THE ENUMERATION OF SCOTLAND, IS INSCRIBED, BY HIS MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT, JAMES LUMSDEN. It would be unjust not to mention, in this place, that Mr. Cleland has transmitted printed documents, containing very numerous and very useful Statistical Details concerning the City and Suburbs of Glasgow, and that the example has produced imitation in some other of the principal Towns in Scotland, though not to the same extent of mi- nute investigation by which Mk. Cleland's labours are distinguished. GOVERNMENT ENUMERATION VOLUME, 1821. ADVERTISEMENT. The digests of the various Government Enu- merations of this Country do great honour to the talents and industry of the Gentleman who has been selected for collecting and arranging them. A perusal of these elaborate and useful documents, suggested the idea of requesting per- mission to publish that part of the last Enumer- ation which relates to Scotland. -

Central Community Profile

Shetland Islands Council Community Profile Central Mainland COMMUNITY PROFILE Central Mainland Shetland Islands Council Community Work Service December 2010 Page 1 of 31 Shetland Islands Council Community Profile Central Mainland Page 2 of 31 Shetland Islands Council Community Profile Central Mainland CONTENTS Page 4 Introduction Placing the West Mainland Community Profile in context Page 6 The West Mainland of Shetland A summary of the facilities, communities and uniqueness of the area Page 7 Population Outlining trends in our population throughout the West Mainland of Shetland Page 11 Cross Cutting Themes Page 14 Wealthier Highlighting how businesses and people are increasing their wealth, enabling more people to share fairly in that wealth Page 18 Fairer Outlining a fairer society Page 20 Smarter Outlining how the area is expanding opportunities to succeed from nurture through to lifelong learning, ensuring higher and more widely shared achievements Page 22 Safer Helping communities to flourish, becoming stronger, safer places to live, offering improved opportunities and a better quality of life Page 23 Stronger Housing, Transport, Community Assets & Communications Page 26 Healthier Helping people to sustain and improve their health, especially in disadvantaged communities, ensuring better, local and faster access to health care Page 27 Greener Improving Shetland’s natural and built environment and the sustainable use and enjoyment of it Page 30 Appendices Page 31 Sources of Information Page 3 of 31 Shetland Islands Council Community Profile Central Mainland Introduction This document presents a range of social, environmental and cultural information focussing on the Central Mainalnd of Shetland and includes the communities of Scalloway, Burra, Trondra, Tingwall and Girlsta. -

Scalloway Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Scalloway Conservation Area Character Appraisal August 2010 Front cover (L – R): Main Street, Scalloway, 1930s, Shetland Museum and Archives ; The Islands of Shetland, H. Moll, 1745, National Library of Scotland ; New Street, Scalloway, Austin Taylor Photography Prepared for Shetland Islands Council by the Scottish Civic Trust. 2 Scalloway Conservation Area Appraisal Contents 1 Introduction, Purpose and Justification 1.1 Date and reason for designation 1.2 What does conservation area status mean? 1.3 Purpose of appraisal 1.4 Planning policy context 2 Location and landscape 2.1 Regional context & relationship to surroundings 2.2 Geology 2.3 Topography 2.4 Planned landscapes 3 Historical Development 3.1 Settlement development 4 Character and Appearance 4.1 Spatial Analysis • Activities/Uses • Street pattern • Plot pattern • Circulation & permeability • Open spaces, trees and landscape • Views, landmarks & focal points 4.2 Buildings and Townscape • Building types • Scheduled monuments • Key listed and unlisted buildings • Materials & local details • Public realm • Condition 4.3 Character Areas 5 Key Features / Assessment of Significance 6 Negative Factors 7 Sensitivity Analysis 8 Opportunities for Preservation & Enhancement 9 Monitoring and Review Appendix 1 – Listed Buildings in the conservation area Appendix 2 – Further Guidance 3 1 Introduction, Purpose and Justification 1.1 Date and reason for designation The Shetland Islands area has 3 conservation areas; 2 in Lerwick and 1 in Scalloway. The Scalloway Conservation Area was designated in 1982 in recognition of its harbour setting and its buildings worthy of preservation. 1.2 What does conservation area status mean? The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997 states that conservation areas “are areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance.” Local authorities have a statutory duty to identify and designate such areas. -

List of the Old Parish Registers Shetland

List of the Old Parish Registers Shetland OPR SHETLAND 1. BRESSAY; BURRA AND QUARFF 1/1 Bressay B 1737-1820 M 1765-1821 D 1786-1820 Burra and Quarff B 1755-1835 M - D - Bressay B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-49 1/3 Burra B 1820-54 M 1820-50 D 1820-43 Quarff B 1793-54 M 1830-55 D 1830-49 2. DELTING 2/1 B 1751-1819 M 1751-1820 D - 2/2 B 1820-55 M 1820-55 D - 3. DUNROSSNESS; SANDWICK AND CUNNINGSBURGH; FAIR ISLE 3/1 Dunrossness* B 1753-1820 M 1753-1819 D - 3/2 Sandwick and Cunningsburgh B 1731-1819 M 1730-1819 D - Fair Isle B 1767-1839 M 1789-1826 D - 3/3 Dunrossness* B 1820-1854 M 1820-1854 D - 3/4 Sandwick and Cunningsburgh; Fair Isle B 1819-54 M 1820-54 D - See library reference MT 001.001 for transcript of Dunrossness B 1795- 1854 allegedly made from the OPR but which contains some entries not in the OPR 4. FETLAR AND NORTH YELL* 4/1 Fetlar B 1754-1820 M 1802-20 D 1803 North Yell B 1787-1819 M 1785-1819 D - 4/2 Fetlar B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1821-54 * See Appendix 1 under reference CH2/151 List of the Old Parish Registers Shetland OPR 4/3 North Yell B 1820-54 M 1816-54 D - 5. LERWICK 5/1 B 1728-1819 M 1706-1819 D 1751-1819 5/2 B 1819-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 RNE 6.