Evidence Report On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liothyronine Sodium(BANM, Rinnm) Potassium Perchlorate

2174 Thyroid and Antithyroid Drugs with methodological limitations. However, a controlled trial of In myxoedema coma liothyronine sodium may be liothyronine with paroxetine could not confirm any advantage of given intravenously in a dose of 5 to 20 micrograms by 3 O additive therapy. slow intravenous injection, repeated as necessary, usu- 1. Aronson R, et al. Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treat- HO I ally at intervals of 12 hours; the minimum interval be- ment of refractory depression: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychi- OH atry 1996; 53: 842–8. tween doses is 4 hours. An alternative regimen advo- 2. Altshuler LL, et al. Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tri- NH2 cates an initial dose of 50 micrograms intravenously cyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of I O the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1617–22. followed by further injections of 25 micrograms every 3. Appelhof BC, et al. Triiodothyronine addition to paroxetine in I 8 hours until improvement occurs; the dosage may the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Endocrinol then be reduced to 25 micrograms intravenously twice Metab 2004; 89: 6271–6. (liothyronine) daily. Obesity. Thyroid drugs have been tried in the treatment of obes- Liothyronine has also been given in the diagnosis of ity (p.2149) in euthyroid patients, but they produce only tempo- NOTE. The abbreviation T3 is often used for endogenous tri-io- hyperthyroidism in adults. Failure to suppress the up- rary weight loss, mainly of lean body-mass, and can produce se- dothyronine in medical and biochemical reports. Liotrix is USAN rious adverse effects, especially cardiac complications.1 for a mixture of liothyronine sodium with levothyroxine sodium. -

Common Thyroid Disorders

9/7/17 Common Louie Riesch MSN, MPH, RN, ACNS-BC, CDE Thyroid Texas Diabetes and Endocrinology Disorders Anatomy of the Thyroid Gland Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis Physiology Hypothalamus TRH • TSH reflects tissue thyroid – hormone actions • TSH as an index of Pituitary therapeutic success and – potential toxicity TSH T4 Target Tissues T3 Heart Thyroid Gland Liver T4 T3 TR Bone T4 è T3 Liver CNS 1 9/7/17 Production of T4 and T3 Ê T4 is the primary secretory product of the thyroid gland, which is the only source of T4 Ê The thyroid secretes approximately 100 nmol of T4 per day Ê T3 is derived from 2 processes Ê The total daily production rate of T3 is about 15-30 µg Ê About 80% of circulating T3 comes from deiodination of T4 in peripheral tissues Ê Largely liver and kidneys Ê About 20% comes from direct thyroid secretion Free Hormone Concept Ê Only unbound (free) hormone has metabolic activity and physiologic effects Ê Total hormone concentration Ê Normally is kept proportional to the concentration of carrier proteins Ê Is kept appropriate to maintain a constant free hormone level 2 9/7/17 Drugs and Conditions That Increase Serum T4 and T3 Levels by Increasing TBG Drugs that increase TBG Conditions that increase TBG Ê Oral contraceptives and other Ê Pregnancy sources of estrogen Ê Infectious/chronic active Ê Methadone hepatitis Ê Clofibrate Ê HIV infection Ê 5-Fluorouracil Ê Biliary cirrhosis Ê Heroin Ê Acute intermittent porphyria Ê Tamoxifen Ê Genetic factors Evaluate for thyroid disease Ê All >35 years of age, every 5 years Ê -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

Liothyronine Sodium(BANM, Rinnm) Potassium Perchlorate

2174 Thyroid and Antithyroid Drugs with methodological limitations. However, a controlled trial of In myxoedema coma liothyronine sodium may be liothyronine with paroxetine could not confirm any advantage of given intravenously in a dose of 5 to 20 micrograms by 3 O additive therapy. slow intravenous injection, repeated as necessary, usu- 1. Aronson R, et al. Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treat- HO I ally at intervals of 12 hours; the minimum interval be- ment of refractory depression: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychi- OH atry 1996; 53: 842–8. tween doses is 4 hours. An alternative regimen advo- 2. Altshuler LL, et al. Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tri- NH2 cates an initial dose of 50 micrograms intravenously cyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of I O the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1617–22. followed by further injections of 25 micrograms every 3. Appelhof BC, et al. Triiodothyronine addition to paroxetine in I 8 hours until improvement occurs; the dosage may the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Endocrinol then be reduced to 25 micrograms intravenously twice Metab 2004; 89: 6271–6. (liothyronine) daily. Obesity. Thyroid drugs have been tried in the treatment of obes- Liothyronine has also been given in the diagnosis of ity (p.2149) in euthyroid patients, but they produce only tempo- NOTE. The abbreviation T3 is often used for endogenous tri-io- hyperthyroidism in adults. Failure to suppress the up- rary weight loss, mainly of lean body-mass, and can produce se- dothyronine in medical and biochemical reports. Liotrix is USAN rious adverse effects, especially cardiac complications.1 for a mixture of liothyronine sodium with levothyroxine sodium. -

Hyper and Hypothyroidism

Editing File Mnemonic File Endocrine Block Pharmacology team 438 Hyper and Hypothyroidism Objectives: By the end of the lecture , you should know: ● Describe different classes of drugs used in hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism and their mechanism of action ● Understand their pharmacological effects, clinical uses and adverse effects ● Recognize treatment of special cases such as hyperthyroidism during pregnancy, Graves’ disease and Thyroid Storm and special cases of hypothyroidism such as myxedema coma Color index: Black : Main content Purple: Females’ slides only Red : Important Grey: Extra info or explanation Blue: Males’ slides only Green : Dr. notes Hyperthyroidism Thyroid Function ● Normal amount of thyroid hormones are essential for normal growth and development by maintaining the level of energy metabolism in the tissue. ● Either too little or too much thyroid hormones will bring disorders to the body. Important Functions CVS: increase Growth & Thermoregulation Helps maintain heart rate & development, increase basal metabolic cardiac output especially in the metabolic rate energy balance which increase embryo & brain (BMR) oxygen demand Iodine Importance ● Thyroid hormones are unique biological molecules in that they incorporate iodine1 in their structure ● Adequate iodine intake (diet, water) is required for normal thyroid hormone production ● Major sources of iodine are: iodized salt, iodated bread, dairy products, shellfish ● Minimum requirement: 75 micrograms/day Iodine Metabolism 1 2 3 Iodide taken up by the Dietary iodine -

Thyroid Disorders: a Multi-Disciplined Analysis

Thyroid Disorders: A Multi-Disciplined Analysis Author: Chadwick J. Szylvian Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/695 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Thyroid Disorders: A Multi-Disciplined Analysis Chadwick Szylvian Advised by Dr. John Wing, Ph. D. Boston College, Biology Department Cover image: “Echography of the thyroid gland”. Courtesy of CARRAT Medical Laboratory Tests Thyroid Disorders: A Multi-Disciplined Analysis Authored by Chadwick Szylvian, Boston College 2009 Introduction 3 I. The Endocrine System and the Thyroid Function 5 The Thyroid 6 II. Physiology The Endocrine System 8 The Thyroid and Coordinated Organs 8 Hyperthyroidism 10 Hypothyroidism 12 Human Development 14 III. Molecular Analysis Hormonal Analysis 19 Cellular Receptors of Thyroid Hormones 19 Non-Receptor, Molecular and Genetic Defects Leading to Thyroid Disorders 23 IV. Clinical Considerations – Testing, Pharmacology, and Systemic Integration Testing 26 Pharmacology 29 Thyroid Disorders and the Pharmaceutical Industry 32 Systemic Ramifications of Abnormal Thyroid Functioning 35 Advancing Treatments 37 Dietary Supplements and Thyroid Disorders 38 V. Closing Author Commentary 39 VI. Figures and Diagrams 40 VII. References 46 2 Introduction Despite weighing barely more than an ounce, the tiny butterfly-shaped thyroid gland is a vital metabolic regulator of the endocrine system. The body depends on this tissue of thyroid cells to produce a unique set of hormone products that perfuse throughout the body to maintain homeostatic metabolic function; the importance of this unassuming collection of cells cannot be underestimated. -

Manual Das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras

MDCB Manual das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras Organizadores Lauro D. Moretto Volume Rosana Mastelaro 16 2013 MDCB Manual das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras Organizadores Lauro D. Moretto Volume Rosana Mastelaro 16 2013 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) MDCB : Manual das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras / coordenadores Lauro D. Moretto, Rosana Mastelaro. -- São Paulo : SINDUSFARMA, 2013. -- (Manuais SINDUSFARMA ; v. 16) 1. Medicamentos - Brasil - Nomenclatura I. Moretto, Lauro D.. II. Mastelaro, Rosana. III. Série. CDD-615.1014 13-03273 NLM-QV-704 Índices para catálogo sistemático: 1. DCB : Denominações Comuns Brasileiras : Ciências farmacêuticas 615.1014 2. Fármacos ou medicamentos : Denominações Comuns Brasileiras : Nomenclatura : Ciências farmacêuticas 615.1014 3. fármacos ou medicamentos : denominações comuns brasileiras : Nomenclatura : Ciências farmacêuticas QV-704 Copyright 2013 Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Todos os direitos reservados. É permitida a reprodução parcial ou total desta obra, desde que citada a fonte. Manual das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras O SINDUSFARMA – Sindicato da Indústria de Produtos Farmacêuticos no Estado de São Paulo elaborou este livro, MDCB – Manual das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras, em conjunto com a ANVISA contendo, na íntegra, os textos das Resoluções RDC n° 63, de 28 de dezembro de 2012 e RDC nº 64, de 28 de dezembro de 2012 que, respectivamente, definem os critérios de nomenclatura e a relação atualizada das Denominações Comuns Brasileiras vigentes. Este compêndio tem por escopo facilitar a consulta e utilização das DCBs, em complemento à versão eletrônica disponibilizada pela ANVISA. Com isso o SINDUSFARMA, coerente com a sua política de prover atualização dos temas técnico-regulatórios, edita este manual e o coloca à disposição dos profissionais do quadro associativo e do corpo de funcionários da ANVISA que atuam em áreas farmacêuticas. -

X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis Method Röntgenfluoreszenz-Analyseverfahren Procédé D’Analyse Par Rayons X Fluorescents

(19) & (11) EP 2 084 519 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: G01N 23/223 (2006.01) G01T 1/36 (2006.01) 01.08.2012 Bulletin 2012/31 C12Q 1/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 07874491.9 (86) International application number: PCT/US2007/021888 (22) Date of filing: 10.10.2007 (87) International publication number: WO 2008/127291 (23.10.2008 Gazette 2008/43) (54) X-RAY FLUORESCENCE ANALYSIS METHOD RÖNTGENFLUORESZENZ-ANALYSEVERFAHREN PROCÉDÉ D’ANALYSE PAR RAYONS X FLUORESCENTS (84) Designated Contracting States: • BURRELL, Anthony, K. AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL PL PT RO SE SI SK TR (74) Representative: Albrecht, Thomas Kraus & Weisert (30) Priority: 10.10.2006 US 850594 P Patent- und Rechtsanwälte Thomas-Wimmer-Ring 15 (43) Date of publication of application: 80539 München (DE) 05.08.2009 Bulletin 2009/32 (56) References cited: (60) Divisional application: JP-A- 2001 289 802 US-A1- 2003 027 129 12164870.3 US-A1- 2003 027 129 US-A1- 2004 004 183 US-A1- 2004 017 884 US-A1- 2004 017 884 (73) Proprietors: US-A1- 2004 093 526 US-A1- 2004 235 059 • Los Alamos National Security, LLC US-A1- 2004 235 059 US-A1- 2005 011 818 Los Alamos, NM 87545 (US) US-A1- 2005 011 818 US-B1- 6 329 209 • Caldera Pharmaceuticals, INC. US-B2- 6 719 147 Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US) • GOLDIN E M ET AL: "Quantitation of antibody (72) Inventors: binding to cell surface antigens by X-ray • BIRNBAUM, Eva, R. -

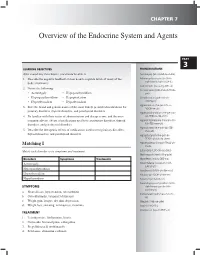

Overview of the Endocrine System and Agents

CHAPTER 7 Overview of the Endocrine System and Agents PART 3 LEARNING OBJECTIVES PRONUNCIatIONS After completing this chapter, you should be able to Acromegaly (ak-roh-MEG-uh-lee) 1. Describe the negative feedback system used to regulate levels of many of the Adrenocorticotropic (uh-DREE- body’s hormones noh-kawr-ti-koh-TROP-ik) Calcimimetic (kal-si-my-MET-ik) 2. Define the following: Corticotropin (KOR-tih-koh-TROH- • Acromegaly • Hypoparathyroidism pin) • Hyperparathyroidism • Hypopituitarism Gonadotropin (goh-nad-uh- • Hyperthyroidism • Hypothyroidism TROH-pin) Hypercalciuria (hie-per-KAL-si- 3. State the brand and generic names of the most widely prescribed medications for YOOR-ee-uh) pituitary disorders, thyroid disorders, and parathyroid disorders Hyperparathyroidism (HIE-per-par- 4. Be familiar with their routes of administration and dosage forms, and the most uh-THIE-roi-diz-uhm) common adverse effects of medications used to treat pituitary disorders, thyroid Hyperphosphatemia (hie-per-FOS- disorders, and parathyroid disorders fuh-TEE-mee-uh) Hypocalcemia (hie-poh-kal-SEE- 5. Describe the therapeutic effects of medications used to treat pituitary disorders, mee-uh) thyroid disorders, and parathyroid disorders Hypopituitarism (hie-poh-pi- TOOH-uh-tuh-riz-uhm) Matching I Hypothalamus (hie-poh-THAL-uh- muhs) Match each disorder to its symptoms and treatment. Luteinizing (LOO-tin-eye-zing) Methimazole (meth-IM-a-zole) Disorders Symptoms Treatments Myxedema (mik-si-DEE-ma) Acromegaly Osteomalacia (os-tee-oh-muh- LAY-shuh) Hyperparathyroidism Parathyroid (PAYR-uh-thie-roid) Hyperthyroidism Pituitary (pi-TOOH-uh-ter-ee) Hypothyroidism Prolactin (proh-LAK-tin) Pseudohypoparathyroidism (SOO- SYMPTOMS doh-hie-po-par-uh-THIE- roid-is-um) a. -

Thyroid Diagnostic Procedures, Treatment and Prevention

THYROID DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES, TREATMENT AND PREVENTION Jassin M. Jouria, MD Dr. Jassin M. Jouria is a medical doctor, professor of academic medicine, and medical author. He graduated from Ross University School of Medicine and has completed his clinical clerkship training in various teaching hospitals throughout New York, including King’s County Hospital Center and Brookdale Medical Center, among others. Dr. Jouria has passed all USMLE medical board exams, and has served as a test prep tutor and instructor for Kaplan. He has developed several medical courses and curricula for a variety of educational institutions. Dr. Jouria has also served on multiple levels in the academic field including faculty member and Department Chair. Dr. Jouria continues to serves as a Subject Matter Expert for several continuing education organizations covering multiple basic medical sciences. He has also developed several continuing medical education courses covering various topics in clinical medicine. Recently, Dr. Jouria has been contracted by the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital’s Department of Surgery to develop an e-module training series for trauma patient management. Dr. Jouria is currently authoring an academic textbook on Human Anatomy & Physiology. Abstract Management of the common forms of thyroid disease has undergone significant study and development, as evidenced by the latest guidelines to diagnose and treat the thyroid. Because the thyroid gland’s role is so pervasive in the body, it is important for clinicians to understand the symptoms of various thyroid diseases. The diagnosis and treatment of thyroid conditions are discussed. 1 nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com Policy Statement This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of NurseCe4Less.com and the continuing nursing education requirements of the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation for registered nurses. -

Thyroid & Antithyroid Drugs

Thyroid & Antithyroid Drugs 1 Three hormones are secreted by the thyroid gland • thyroxine (3,5,3,5-tetraiodothyronine, orT4), •triiodothyronine (3,5,3-triiodothyronine,or T3), •Calcitonin •Every tissue in the body is affected in some way by thyroid hormones, and almost all cells appear to require constant optimal amounts for normal operation. 2 structural of the thyroid gland *Thyroid follicles are the structural & functional units of the thyroid gland. * Each follicle is surround mainly by simple cuboidal epithelium and is filled with a colloid * Thyroid hormones are mainly synthesized in colloid while the simple cuboidal epithelium undertaking thyroglobulin production, iodide intake & thyroid hormones release. •Thyroglobulin (Tg) is a 660 kDa, dimeric protein produced by the follicular cells of the thyroid and used entirely within the thyroid gland. •Thyroglobulin protein accounts for approximately half of the protein content of the thyroid gland ●Synthesis of thyroid hormones Thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) tetraiodothyronine (T4, thyroxine) Materials iodine & tyrosine MIT: monoiodotyrosine DIT: diiodotyrosine 4 Steps 1. Iodide is trapped by sodium-iodide symporter 2. Iodide is oxidized by thyroidal peroxidase to iodine 3. Tyrosine in thyroglobulin is iodinated and forms MIT & DIT 4. Iodotyrosines condensation MIT+DIT→T3; DIT+DIT→T4 5 synthesis of thyroidal hormones 1. Iodide is taken up at the basolateral cell membrane and transported to the apical membrane 2. Polypeptide chains of Tg (thyroglobulin) are synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, and posttranslational modifications take place in the Golgi 3. Newly formed Tg is transported to the cell surface in small apical vesicles (AV) 4. Within the follicular lumen, iodide is activated and iodinates tyrosyl residues on Tg, producing fully iodinated Tg containing MIT, DIT, T4 and a small amount of T3 (organification and coupling), which is stored as colloid in the follicular lumen 6 synthesis of thyroidal hormones 5. -

Drug-Induced Hyperthermic Syndromes Part I

Drug-Induced Hyperthermic Syndromes Part I. Hyperthermia in Overdose a,b, a Bryan D. Hayes, PharmD *, Joseph P. Martinez, MD , a,c Fermin Barrueto Jr, MD KEYWORDS Hyperthermia Thermoregulatory system Hypermetabolism Sympathomimetics Cocaine Methlenedioxymethamphetamine Anticholinergics Salicylates KEY POINTS Drugs and natural compounds that affect the thermoregulatory system can induce or contribute to hyperthermia when used in excess. Hyperthermia associated with drug overdose is dangerous and potentially lethal. Appropriate treatment strategies such as cooling and the administration of counteractive medications are discussed. Emergency physicians frequently manage patients with drug overdoses. When the ingested drug induces reactions that cause hyperthermia, the diagnostic process and treatment become particularly challenging. Although the terms fever and hyper- thermia are commonly used interchangeably, they are not equivalent. Fever is the normal physiologic response to an inflammatory pyrogen, and hyperthermia is an elevated core body temperature. Drugs and toxins that affect the thermoregulatory system can cause or contribute to hyperthermia through one of two mechanisms: increased production of heat or impaired ability to dissipate heat. The body is sensitive to temperature changes. Severe or prolonged hyperthermia can result in disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), delirium, rhabdomyolysis, and death.1 This article discusses sympathomimetics, Funding Sources: Nothing to disclose. Conflict of Interest: Nothing to disclose. a Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 110 South Paca Street, Sixth Floor, Suite 200, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; b Department of Pharmacy, University of Maryland Medical Center, 22 South Greene Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; c Department of Emergency Medicine, Upper Chesapeake Health Systems, 500 Upper Chesa- peake Drive, Bel Air, MD 21015, USA * Corresponding author.