Militarized Journalism: Framing Dissent in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coverage and Outreach

Global Carbon Project – Future Earth Carbon Budget 2017 Published 13 November 2017 Coverage and Outreach News agency promo-poster in Melbourne, Australia, 14 Nov. 2017 This document gives an overview of the coverage and outreach of the Global Carbon Budget 2017 release and associated publications and activities. It is intended to inform the team on how their work was reported and perceived worldwide. It is not exhaustive but still provides much detail to guide future outreach efforts. PRODUCTS 13 NOV 2018 1. Three papers (ESSD-CorinneL, NatureCC-GlenP, ERL-RobJ) 2. Data and ppt 3. GCP carbon budget webpage updates 4. Global Carbon Atlas updates 5. One Infographic 6. One Video (English, Spanish) 7. Two blogs (The Conversation-Pep, CarbonBrief-Glen) 8. Seven press releases (UEA, CICERO, Stanford University, CSIR-South Africa, China-Fundan University, Future Earth, European Climate Foundation) 9. Multiple Twitter and Facebook feeds. 10. Key Messages document (internal) SUMMARY OF COVERAGE AND OUTREACH • Media outlet coverage within the first week after publication (print and online; based on Meltwater searches on “Global Carbon Project”, “Global Carbon Budget”, “Global Carbon Budget 2017” and “2017 Global Carbon Budget” run by European Climate Foundation): Global coverage in 99 countries with a total of 2,792 media items (this count doesn’t include UK media), in 27 different languages. • OECD dominates coverage (particularly USA, UK, France, Germany, Canada, and Australia), but almost equally large coverage in China, India and Brazil (a great leap forward over previous years). South east Asia and Central/South America (except Brazil) some coverage too. Key to this success was working for the first time with the Climate Change Foundation facilitated by Future Earth (Owen, Alistair). -

Configuring Logos on the DNCS User Guide

738163 R ev B Configuring Logos on the DNCS User Guide Please Read Important Please read this entire guide. If this guide provides installation or operation instructions, give particular attention to all safety statements included in this guide. Notices Trademark Acknowledgments Cisco and the Cisco logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Cisco and/or its affiliates in the U.S. and other countries. A listing of Cisco's trademarks can be found at www.cisco.com/go/trademarks. Third party trademarks mentioned are the property of their respective owners. The use of the word partner does not imply a partnership relationship between Cisco and any other company. (1009R) Publication Disclaimer Cisco Systems, Inc. assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions that may appear in this publication. We reserve the right to change this publication at any time without notice. This document is not to be construed as conferring by implication, estoppel, or otherwise any license or right under any copyright or patent, whether or not the use of any information in this document employs an invention claimed in any existing or later issued patent. Copyright © 2008, 2010, 2012 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Information in this publication is subject to change without notice. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by photocopy, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without the express permission of Cisco Systems, Inc. Contents About This Guide v Logo Overview 1 Logo Types ............................................................................................................................... -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 04-227 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) ELEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: January 14, 2005 Released: February 4, 2005 By the Commission: Chairman Powell issuing a statement; Commissioners Copps and Adelstein concurring and issuing a joint statement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................1 A. Scope of this Report..................................................................................................................2 B. Summary of Findings ..............................................................................................................4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2004 ...................................................................4 2 General Findings .........................................................................................................7 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING......16 A. Cable Television Service.......................................................................................................16 1. General Performance.................................................................................................17 2. Capital Acquisition and Disposition.........................................................................33 -

The Media Reform Models of Progressive Television Journalists

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reforming the American Public Sphere: The Media Reform Models of Progressive Television Journalists in the Era of Internet Convergence and Neoliberalism A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Adam Richard Fish 2012 © Copyright by Adam Richard Fish 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reforming the American Public Sphere: The Media Reform Models of Progressive Television Journalists in the Era of Internet Convergence and Neoliberalism by Adam Richard Fish Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sherry B. Ortner, Chair Based on ethnographic data, this dissertation analyzes the broadcasting and media reformative models of workers in American television and internet video news networks. Media reform broadcasters seek to diversify the American public sphere as a counterhegemonic movement through recursively using technology and policy to create access for increased diversity of voice. Their challenges illustrate the problems for democracy in a neoliberal state. ii This dissertation of Adam Richard Fish is approved. Christopher Kelty Akhil Gupta John T. Caldwell Sherry B. Ortner, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2012 iii Dedicated to my grandparents Mary and Dick Cook and my wife and daughter, Robin and Isis Viola Lune Fish. iv INTRODUCTION: THE CULTURAL INTERVENTIONS OF MEDIA REFORM BROADCASTERS 1 REACTIVE DISCOURSES AND THE MODELS OF MEDIA REFORM BROADCASTERS -

5337 Programminglineup.R16

Movies HBO Plus (East & West). A perfect complementary choice to what’s on HBO. Scheduled for the broadest appeal, this channel doubles your HBO entertainment options. American Movie Classics is the premiere 24-hour movie network featuring award-winning original productions about the world of American film. With one of the finest, most comprehensive libraries of classic films and a diverse blend of original series and documentaries, AMC offers in-depth information on timeless and contemporary HBO Signature. Discriminating viewers will enjoy HBO’s critically acclaimed, Hollywood classics. award-winning original movies, series and documentaries, plus theatrical films. Cinemax® (East & West). With over 1,600 different movies a year, Cinemax gives viewers the widest variety of movies from its vast inventory with a different movie every night at The Independent Film Channel (IFC). The first network entirely dedicated to capturing and 8pm ET all year long! presenting the irreverent style of independent film, uncut and commercial-free, 24 hours a day. IFC presents the most extensive independent film collection on television like “Trainspotting,” “In the Company of Men,” and “Secrets and Lies,” combined with original series, exclusive ™ live events like the Independent Spirit Awards and the Cannes Film Festival and enhanced new MoreMAX. Doubles your Cinemax film choices with popular, hard-to-find movies. Features media programming. Featured indie celebs include Spike Lee, John Waters and Lili Taylor. daily classics and special premieres of foreign and independent films. The New Encore (East & West). The ultimate, commercial-free movie channel destination The Movie Channel (East & West). For people who just want to have movies, The Movie because it now delivers a great movie every night. -

Federal Communications Commission APPENDIX a List Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 99-418 APPENDIX A List ofCommenters Initial Comments American Cable Association ("ACA") Ameritech New Media, Inc. ("Ameritech") AT&T Corp. ("AT&T') BellSouth Corporation {"BellSouth") DirecTV, Inc. ("DirecTV") EchoStar Satellite Corporation {"EchoStar") Hiawatha Broadband Communications, Inc. ("Hiawatha") MediaOne Group, Inc. ("MediaOne") MICROCOM - Anchorage, Alaska ("Microcom") National Cable Television Association, Inc. ("NCTA") National Rural Telecommunications Cooperative ("NRTC") OpTel, Inc. ("OpTel") RCN Corporation ("RCN") Satellite Broadcasting and Communications Association ("SBCA") Wireless Communications Association International, Inc. ("WCA") Reply Comments Cablevision Systems Corporation ("Cablevision") Comeast Corporation ("Comcast") Competitive Cable Coalition ("Coalition") CoreComm Limited ("CoreComm") DirecTV, Inc. ("DirecTV") Lifetime Entertainment Services ("Lifetime") Mainstreet Communications and Unitel Communications {"Mainstreet") National Cable Television Association, Inc. ("NCTA") National Rural Telecommunications Cooperative ("NRTC') RCN Corporation ("RCN") Seren Innovations, Inc. ("Seren") Speedvision Network. L.L.c. and Outdoor Life Network, L.L.c. ("Speedvision") Viacom Inc. ("Viacom") Walt Disney Company, Inc. ("Disney") A-I Federal Communications Commission FCC 99-418 APPENDIXB TABLE B-1 0 Cable Television Industry Growth: 1991 - June 19994 ) (in millions) 1991 92.1 1.1% 88.4 2.8% 53.4 3.3% 96.0% 58.0"10 60.4% 1992 93.1 1.1% 89.7 1.5% 55.2 3.4% 96.3% 59.3% 61.5% 1993 94.0 1.0% 90.6 1.0% 57.2 3.6% 96.4% 60.9% 63.1% 1994 94.9 1.0% 91.6 1.1% 59.7 4.4% 96.5% 62.9% 65.2% 1995 95.9 1.1% 92.7 1.2% 62.1 4.0% 96.7% 64.8% 67.0% 1996 97.0 1.1% 93.7 1.1% 63.5 2.3% 96.6% 65.5% 67.8% 1997 98.0 1.0% 94.6 1.0% 64.9 2.2% 96.5% 66.2% 68.6% 1998 99.0 1.0% 95.6 1.1% 66.1 1.8% 96.6% 66.8% 69.1% Jun 99(e) 99.5 0.5% 96.1 0.5% 66.7 0.9% 96.6% 67.0% 69.4% (e) June data based on year-end estimate by Paul Kagan Associates. -

Digital Cable Lineup

Time Warner Cable Digital Cable Box 1 iCONTROL 136 Fine Living 332 ESPN Sports 2 2 Commercial Access 137 CNBC World 333 ESPN Sports 3 3 WXIX FOX - 19 138 Discovery Home & Leisure 334 ESPN Sports 4 4 Community Access 139 Discovery Times 335 ESPN Sports 5 5 WLWT NBC - 5 140 Country Music Television 336 ESPN Sports 6 6 TBS 141 AmericanLife 341 MLB / NHL 1 7 PAX TV 142 G4TECH TV 342 MLB / NHL 2 8 Community/Religion 143 Boomerang 343 MLB / NHL 3 9 WCPO ABC - 9 144 IFC 344 MLB / NHL 4 10 Headline News 145 MBC 345 MLB / NHL 5 11 WSTR WB - 64 147 Biography Channel 346 MLB / NHL 6 12 WKRC CBS - 12 148 NickToons 347 MLB / NHL 7 13 CET PBS - 48 149 Nick GAS 348 MLB / NHL 8 14 WPTO PBS - 14 Dayton 150 Encore 349 MLB / NHL 9 15 Community/Education 151 Love Stories 350 MLB / NHL 10 16 WPTD PBS - 16 Dayton 152 Westerns 360 NBA Preview Channel 17 ITV / EWTN 153 True Stories 361 NBA 1 18 ITV / TBN 154 WAM 362 NBA 2 19 QVC 155 Mysteries 363 NBA 3 20 Commercial Access / UPN 156 Action 364 NBA 4 21 WCVN PBS - 54 Covington 157 Fox Movie Channel 365 NBA 5 22 Weather Radar 158 Sundance 366 NBA 6 23 CitiCable / Government 160 Encore W 367 NBA 7 24 Metro Access 161 Love Stories W 368 NBA 8 25 Home Shopping Network 162 Westerns W 369 NBA 9 26 Animal Planet 163 True Stories W 370 NBA 10 27 Cartoon Network 165 Mysteries W 371 NBA 11 28 Nickelodeon 166 Action W 905 WLWT HDTV 29 Court TV 169 Shop NBC 909 WCPO HDTV 30 ESPN 170 The Tennis Channel 912 WKRC HDTV 31 ESPN2 171 Fox Sports Atlantic 919 WXIX HDTV 32 ESPN Classic 172 Fox Sports Central 931 ITV 33 USA 173 Fox -

WMG Acquisition Corp. (Exact Name of Co-Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): February 10, 2006 Warner Music Group Corp. (Exact name of Co-Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-32502 13-4271875 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 75 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, New York 10019 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Co-Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 275-2000 WMG Acquisition Corp. (Exact name of Co-Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 333-121322 68-0576630 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 75 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, New York 10019 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Co-Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 275-2000 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ¨ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ¨ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) ITEM 1.01. ENTRY INTO A MATERIAL DEFINITIVE AGREEMENT. -

1-812-961-7008 1-800-Next-Window

-769448-1 HT AndyMohrHonda.com AndyMohrHyundai.com S. LIBERTY DRIVE BLOOMINGTON, IN October 15 - 21, 2020 YOUR FULL-SERVICE TREE EXPERTS Sara Haines has returned as a co- Specializing in 24 hr emergency tree removal service and host of “The View” all aspects of trimming, shaping & dead wood removal. weekdays on ABC. "WE BELIEVE THAT IT'S IMPORTANT TO MAINTAIN A ‘View’ BLOOMINGTON'S CANOPY." she knows well restores [email protected] (812) 332-5882 Sara Haines to ABC’s daytime lineup Call for a 1-812-961-7008 Te Free Home 1-800-Next-Window Nation’s www.windowworldscindiana.com Largest Estimate Window today! Replacement HT -362968-1 Company Veteran Owned and Operated T2 | THE TV TIMES| Sara Haines has ‘The View’ again in return to ABC program DISH INDIANAPOLIS Cable COMCAST BEDFORD NEW WAVE MITCHELL DIRECTV INDIANAPOLIS S NEW WAVE MOOREVILLE COMCAST MARTINSVILLE COMCAST BLOOMINGTON A Conversion T URDAY, OC URDAY, WTWO NBC 2 - - - - - - - WAVE NBC 3 - 3 - - - - - WTTV CBS 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 WRTV ABC 6 6 6 6 6 - 6 6 WTVW IND 7 - - - - - - - WISH IND 8 8 8 8 8 8 - 8 TO WNIN PBS 9 - - - - - - - WTHI 10 BER2020 17, CBS 15 15 - - - - - WHAS ABC 11 - 7 - - - - - WTHR NBC 13 13 13 12 13 12 13 13 WKPC PBS 15 - - - - - - - WHAN IND 17 - - - - - - - WFYI PBS 20 - - 2 3 2 - 20 WNDY MYNET 23 10 10 10 10 10 - 23 WEHT ABC 25 - - - - - - - WTIU PBS 30 5 5 - 5 - 30 30 WLKY CBS 32 - 12 - - - - - WAWV ABC 38 - - - - - - - WHMB IND 40 9 9 5 9 5 - 40 WDRB FOX 41 - 17 - - - - - WCLJ IND 42 2 2 - 2 - - - WMYO NYNET 58 - - - - - - - WXIN FOX 59 11 11 13 11 13 59 59 WIPX ION 63 18 18 3 18 3 - 63 WGN 20 20 9 20 9 307 239 AMC 23 23 23 23 23 254 - USA 25 25 27 25 27 242 105 Whoopi Goldberg, Joy Behar, Sara Haines, Sunny Hostin and Meghan McCain (from left) are ESPN 26 26 18 26 18 115 140 co-hosts of “The View” weekdays on ABC. -

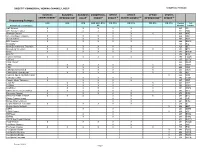

DIRECTV® COMMERCIAL VIEWING CHANNEL LINEUP Programming

DIRECTV® COMMERCIAL VIEWING CHANNEL LINEUP COMMERCIAL PACKAGES BUSINESS BUSINESS BUSINESS COMMERCIAL OFFICE OFFICE OFFICE SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT® INFORMATION® VALUE® CHOICE® CHOICETM ENTERTAINMENTTM INFORMATIONTM CHOICETM Programming Packages HOS HOS HOS BAR, BLK, GOV, FIR, POL FIR, POL FIR, POL FIR, POL Channel Call Available to account types: OIL Number Letters A&E Network X X X X X 265 AE ABC Family Channel X X X X X 311 FAM All News Channel X X X 364 ANC American Movie Classics X X X X X 254 AMC Animal Planet X X X X X 282 ANP BBC America X X X X X 264 BBCA Biography 266 BIO Black Entertainment Television X X X X X 329 BET Bloomberg Television X X X X X X X 353 BTV Bravo X X X X X 273 BRVO BYU TV* 374 BYU Cartoon Network X X X X X 296 TOON CCTV-9* 455 CCTV Clara+Vision* 438 CLAR CNBC X X X X X 355 CNBC CNN X X X X X 202 CNN CNN/Sports Illustrated X X X X 205 CNSI CNNfn/CNN International X X X X X 358 fn/l Comcast Sports Net Mid-Atlantic X 629 CSN Comedy Central X X X X X 249 COM Country Music Television X X X X X 327 CMT Court TV X X X X X 203 CRT C-SPAN X X X X X 350 CSP1 C-SPAN 2 X X X X X 351 CSP2 DIRECTV FreeView Channel X X X X X X X 103 DTV Discovery Channel X X X X X 278 DISC Discovery Health Channel X X X X X X 279 DHC Disney Channel (East) X X 290 DIS1 Disney Channel (West) X X 291 DIS2 E! Entertainment Television X X X X X 236 E! Empire Sports Network X 626 EMP ESPN X X 206 ESPN ESPN Classic X X 606 ESC ESPNews X X 207 ESN2 ESPN2 X X 208 ESN2 EWTN Red Global Catolica* 422 EWTN Food Network X X X X X 231 FOOD Fox Movie Channel -

1 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) ) In the Matter of ) ) EB Docket No. 04-296 Review of the Emergency Alert System ) ) ) ) ) COMMENTS OF THE SATELLITE BROADCASTING AND COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIATION I. Introduction and Summary The Satellite Broadcasting Communications Association (“SBCA” or “Association”) hereby submits its comments to the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC” or “Commission”) in response to the above referenced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.1 The SBCA is the national trade association representing various entities that are engaged in the delivery of television, radio and broadband services directly to consumers via satellite. The Association’s members include C-Band and Direct Broadcast Satellite (“DBS”) carriers and distributors; programming services that offer entertainment, news and sports to consumers over satellite platforms; satellite equipment 1 Review of the Emergency Alert System, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 19 FCC Rcd. 15775 (2004) (“NPRM” or “Notice”). 1 manufacturers and distributors; and satellite dealers and retail firms that sell systems directly in the consumer marketplace. The satellite industry supports the Commission’s efforts to keep the nation’s public alert and warning systems up to date, and, in this regard, SBCA’s two largest members participate in the Commission’s Media Security and Reliability Council (“MSRC”). More specifically, SBCA supports this much-needed reexamination of the Emergency Alert System (“EAS”). EAS is, however, only one of many tools used to disseminate emergency information.2 Americans receive such information from a multiplicity of sources, including broadcast and cable television networks, radio, the Internet, cell phones, Blackberrys and other technologies. During the September 11 terrorist attacks, for example, no single communications path dominated. -

Nascentia Outlines Project Timeline Tomorrow’S Weather Aim to Break Ground in September on New Complex at Former Beeches Location Sponsored by by NICOLE A

Donations aid Vandalism MLB trade recovery effort suspects sought deadline sees in Western in Whitestown plenty of moves Page 2 Page 2 Page 9 157 YEARS FAMILY OWNED ROME, N.Y. SATURDAY, JULY 31, 2021 | OUR 139TH YEAR | $2.00 Showers likely Nascentia outlines project timeline Tomorrow’s weather Aim to break ground in September on new complex at former Beeches location sponsored by BY NICOLE A. HAWLEY Nascentia Health is a company that offers Staff writer managed long-term care and in-home A senior community for ages 55-plus, care services for the elderly, as well as with resources available for home and insurance plans, operating in 48 counties community-based services is planned for throughout Upstate New York. Nascentia Health’s new campus to be According to Rolf, the former Beeches located at the former Beeches Inn and site would not operate as a skilled nurs- Conference Center on Turin Road. ing facility. 1149 Erie Blvd. W. • 315–709–9096 Nascentia has outlined Phase I and “This is not a nursing home. We’ve been working with another company in More weather on page 5 II of their project, with hopes to break ground in September. Syracuse on housing for individuals for Sunday — Showers with Nascentia offi cials reiterated that sev- services we provide here,” Rolf said. The a chance of thunderstorms. eral structural features and amenities Beeches, “would be perfect to have a Highs in the lower 70s. of The Beeches, including the famous retirement-type community.” Chance of rain 80%. Sunday sculpture, a remake of “The Capitoline Plans are that “we’ll be turning it into a night — Showers likely with Wolf,” featuring Remus and Romulus, senior housing community with one-story a chance of thunderstorms.