Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

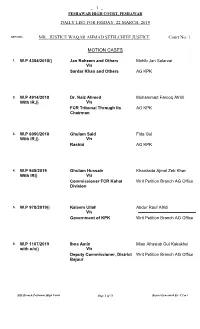

Sb List for 04.02.2019(Monday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 1. CM Corr Nauman Azhar Ali Khan (Nowshehra) 34/2019(in BA 14- V/s P/2019) The State 2. Cr.M(TA) The Bank of Khyber Abd-ur-Rauf Rohaila 96/2018() V/s (Date By Court) The State CrAppeal Branch AG Office 3. CM(TA) 8/2019() Jahangir Syeda Saima Jafferi V/s Amna Bibi 4. W.P 263/2019() Ajmal Khan Altaf Ahmad V/s Fazle Amin Writ Petition Branch AG Office 5. W.P 371/2019 with Ahad Ali Hayat Khan IR() V/s Sardar Ali Writ Petition Branch AG Office 6. Cr.A 1213/2018() Murad Ali Said Jamil Shah V/s The State CrAppeal Branch AG Office MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 95 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 7. Cr.M(BCA) The State CrAppeal Branch AG Office 2707/2018() V/s Gulalai Ismail i Cr.M(BCA) 2708/2018 The State CrAppeal Branch AG Office V/s Fazal Khan 8. coc. 73/2019 in Muhammad Fateh Khan and Muhammad Alam Khan, C.R 316/2016 others Muhammad Sami ur rehman (Declartion)(Again V/s st decree (stay Munir and other Syed Kausar Ali Shah (Mardan) granted on 17/05/2016) 9. C.R 33/2019 with Mian Khan Khalil Arbab Yasir Hayat cm. -

24 October 2019 Pakistan

24 October 2019 Pakistan: Muhammad Ismail, father of woman human rights defender Gulalai Ismail, abducted in Peshawar On 24 October 2019, Muhammad Ismail, the father of Pakistani woman human rights defender Gulalai Ismail, was abducted by a group of unidentified men as he was leaving the Peshawar High Court. The family, supporters and colleagues of Gulalai Ismail have been subjected to relentless threats, intimidation and harassment by officers of the Pakistani Military and Intelligence service since 25 May 2019. Gulalai Ismail is an award-winning woman human rights defender and the co-founder of Aware Girls, who has been compelled to flee Pakistan after two First Information Reports (FIRs) were filed against her on 22 and 23 May 2019 by police in Islamabad. The FIRs accuse her of serious offenses including “sedition” under the Penal Code and Sections 6/7 of the regressive Anti- Terrorism Act. Her father, Muhammad Ismail is a well known human rights defender in Pakistan, and has been critical of human rights violations in the country, particularly the treatment of his daughter by the State apparatus. Front Line Defenders has previously issued an urgent appeal expressing its concern against the filing of false and baseless allegations against Gulalai Ismail and a further appeal condemning the threats against her family, especially her elderly parents and sister. Since May 2019, the family home in Islamabad has been raided by armed military on at least four occasions. During these raids the officials questioned and harassed her parents, confiscated their mobile phones, and photographed Gulalai Ismail’s younger brother, without his consent. -

148-2 2019 DE Pakistan.Pdf(Pdf, 166.13

URGENT ACTION PROFESSOR TROTZ COVID-19- INFEKTION ERNEUT IN HAFT PAKISTAN UA-Nr: UA-148/2019-2 AI-Index: ASA 33/3626/2021 Datum: 3. Februar 2021 – sd PROFESSOR MUHAMMAD ISMAIL Am 2. Februar wurde Professor Muhammad Ismail erneut inhaftiert, nachdem ein Antiterrorgericht in Peshawar seine Freilassung gegen Kaution nicht bestätigt hatte. Der 66-Jährige unterstützt seine Tochter, die Menschenrechtsverteidigerin Gulalai Ismail, und sieht sich einer Anklage wegen „Terrorismus-Finanzierung“ gegenüber. Ihm droht eine langjährige Haftstrafe. Muhammad Ismail wurde kürzlich positiv auf Covid-19 getestet und seine Angehörigen berichten, dass sich sein Gesundheitszustand erheblich verschlechtert habe. Im Falle einer Gefängnisstrafe sind seine Gesundheit und seine Sicherheit in ernsthafter Gefahr. Der erneuten Festnahme von Muhammad Ismail gingen massive Einschüchterungsversuche voraus. Die Familie Ismail wird bereits seit Mai 2019 überwacht, bedroht und eingeschüchtert, ihre Wohnung wurde mehrmals durchsucht. Seit Juli 2019 muss Muhammad Ismail immer wieder vor Gericht erscheinen. Er selbst und seine Frau stehen auf den Flugverbotslisten des Landes, sodass sie ihre Tochter Gulalai Ismail nicht treffen können. Diese musste im September 2019 aus ihrem Heimatland fliehen. Da Muhammad Ismail unter dem drakonischen Antiterrorgesetz und dem Digitalverbrechensgesetz Pakistans angeklagt ist, droht ihm eine langjährige Haftstrafe. Nachdem er sich online für seine Tochter und deren menschenrechtliche Arbeit eingesetzt hatte, sah sich der Professor zunächst Terrorismus-Vorwürfen gegenüber, später lautete die Anklage auf „Aufwiegelung“. Am 2. Juli 2020 sprach das Antiterrorgericht in Peshawar Gulalai Ismail, Muhammad Ismail und seine Frau Uzlifat vom Vorwurf des „Finanzterrorismus“ frei. Doch bereits drei Monate später, am 30. September 2020, wurden sie vom selben Gericht wegen „Aufwiegelung“ und „Terrorismus“ angeklagt – worauf lange Haftstrafen stehen. -

Human Rights in Asia-Pacific

HUMAN RIGHTS IN ASIA-PACIFIC: REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Cover photo: Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed Pro-democracy protesters react as police fire water under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, cannons outside the government headquarters in international 4.0) licence. Hong Kong on September 15, 2019. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Nicolas Asfouri / AFP via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 01/1354/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org HUMAN RIGHTS IN ASIA-PACIFIC REVIEW OF 2019 CONTENTS REGIONAL OVERVIEW 5 AFGHANISTAN 7 AUSTRALIA 10 BANGLADESH 12 CAMBODIA 14 CHINA 16 HONG KONG 19 INDIA 21 INDONESIA 25 JAPAN 27 KOREA (DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF) 29 KOREA (REPUBLIC OF) 31 MALAYSIA 33 MALDIVES 36 MONGOLIA 38 MYANMAR 40 NEPAL 43 NEW ZEALAND 46 PAKISTAN 48 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 51 PHILIPPINES 53 SINGAPORE 56 SRI LANKA 58 TAIWAN 60 THAILAND 62 VIETNAM 65 HUMAN RIGHTS IN ASIA-PACIFIC: 4 REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International physical assaults, abuse in detention – crackdown on Turkic Muslims intensified millions showed their resolve, demanding as the true horrors of the “re-education REGIONAL accountability and insisting on their camps” became apparent. -

Development Advocate

DEVELOPMENT ADVOCATE PAKISTAN Volume 2, Issue 3 October 2015 TheThe Debate Debate onon FATAFATA MainstreamingMainstreaming DEVELOPMENT ADVOCATE PAKISTAN October 2015 CONTENTS Analysis Interviews 02 FATA in perspective Ajmal Khan Wazir 36 Convener and spokesperson, Political Parties Joint Analysis of Key Recommendations for Committee on FATA Reforms 17 FATA Reform Ayaz Wazir Asad Afridi 37 Senior member, Joint Political Parties Committee on Opinion FATA reforms Mainstreaming FATA for its people Ayaz Wazir 18 Dr. Afrasiab Khattak 38 Former Ambassador of Pakistan © UNDP Pakistan Recommendations of the FATA Reforms Brig. (Retd.) Mahmood Shah 20 Commission (FRC) 39 Former Secretary Security FATA, Ejaz Ahmad Qureshi Development Advocate Pakistan provides a platform for the exchange of ideas on key development issues DEVELOPMENT ADVOCATE Farid Khan Wazir and challenges in Pakistan. Focusing on a specic The state of Human Rights in FATA: development theme in each edition, this quarterly Ex-Federal Secretary Ministry of Human the socio-economic perspective 39 publication fosters public discourse and presents 22 Rights Peshawar, Ex-Chief Secretary Northern Areas varying perspectives from civil society, academia, Muhammad Uthmani government and development partners. The PAKISTAN publication makes an explicit effort to include the Reforms in FATA: A Pragmatic Bushra Gohar voices of women and youth in the ongoing discourse. 40 A combination of analysis and public opinion articles Disclaimer 24 Proposition or a Slippery Slope? Senior Vice-President of the Awami National Party promote and inform debate on development ideas The views expressed here by external contributors or the members of Imtiaz Gul whilepresentingup-to-dateinformation. the editorial board do not necessarily re0ect the official views of the Ejaz Ahmad Qureshi organizations they work for and that of UNDP’s. -

Islamabad Peace Exchange – Organisations Attending

ISLAMABAD PEACE EXCHANGE – ORGANISATIONS ATTENDING The Islamabad Peace Exchange aims to bring together a diverse group of civil society organisations from across Pakistan, all of whom share a strong commitment to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. We hope that each participant will bring different experiences and contexts to share, as well as common lessons from their day to day operations. The event will be jointly hosted by the British Council in Pakistan, and the British charity, Peace Direct. Below is a list of the organisations who will be attending. For more information contact John Bainbridge: [email protected] Organisation: Association for Behaviour and Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) Representative: Ms. Shad Begum, Executive Director Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] ; [email protected] The Association for Behaviour & Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) is an organisation of leading social entrepreneurs from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Founded in 1994, it is a nationally recognised NGO that strives to improve the lives of underdeveloped and vulnerable communities, with a special focus on women, youth and children in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. ABKT is currently mobilising and linking young people from across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to ensure their effective and constructive contribution to peace in the region. ABKT has organised many peacebuilding events, such as the Peace and Development Seminar in October 2010, and the District Level Forum on Peace in 2010. Organisation: Aware Girls Representative: Ms. Gulalai Ismail, Chairperson Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] Aware Girls seeks to enable young people from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province and Tribal Area of Pakistan to develop the leadership and peer-education skills necessary for promoting peace and non-violence in the region. -

Case Briefing for Professor Mohammad Ismail

Last updated 4 May 2020 INDIVIDUAL BRIEFING Mohammad Ismail Pakistan Name: M ohammad Ismail Naonality: Pakistani Age: 6 5 Charges: “Hate speech” and “cyber terrorism” Current Status : On bail Mohammad Ismail is a human rights defender and the Secretary of NGOs Forum Pakistan. He is also the elderly father of the award-winning human rights acvist Gulalai Ismail, who founded the charity Aware Girls in 2002. Gulalai was forced to flee to the United States in 2019 aer being persecuted for speaking out against sexual assaults and disappearances carried out by the Pakistani military. In her absence, her family connues to be harassed and inmidated by local authories. The Ismail family has collecvely endured invasive surveillance, threats and inmidaon since May 2019– with their home raided by armed military mulple mes. Professor Ismail was abducted and arbitrarily detained in October 2019, and although currently on bail, he remains at risk of arrest and serving a lengthy detenon period based on mulple spurious charges. Professor Ismail is suffering from health problems, including hypertension, heart and kidney problems, and his detenon will likely exacerbate them. Timeline 23 May 2019 . Professor Ismail’s daughter, Gulalai, is charged with “an-state and hate speech” under the Penal Code and Secons 6/7 of the An-Terrorism Act for protesng the rape and murder of a 10-year old Pashtun girl, aer which she was forced into hiding. 1 1 https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA3313482019ENGLISH.pdf Last updated 4 May 2020 25 May 2019. P olice raid the family home of Mohammad and Gulalai Ismail in Islamabad. -

Gulalai Ismail, Flyer

TACKLING EXTREMISM AND VIOLENCE IN PAKISTAN: THE ROLE OF YOUNG PEOPLE AND WOMEN In a place where lives are shattered by violence and militants rule the streets, one woman took it upon herself to stand up for women’s rights and challenge the power of the Taliban. Flying from her home in Pakistan to talk first-hand about her experiences, hear Gulalai Ismail speak in Edinburgh on Tuesday 13 September, 6pm MEET GULALAI Gulalai was just 16 when she co-founded innovative local organisation, Aware Girls, in Pakistan. Driven by a passion to challenge a culture of intolerance and extremism, Gulalai began running workshops in her home town to provide women with leadership skills to challenge oppression and fight for their rights to an education and equal opportunities. Based in Peshawar, north-west Pakistan, Aware Girls has grown into an internationally renowned organisation that since 2002 has trained, empowered and inspired hundreds of youth in Pakistan. Nobel peace prize winner and victim of the Taliban’s bullets, Malala Yousafzai, was among one of the earliest members. Last year, with the support of international NGO Peace Direct, Gulalai and her team helped over 1,300 young people in Pakistan to challenge extremism. Despite threats against her own life, Gulalai next plans to expand her work into neighbouring Afghanistan. A winner of the 2009 Youth Action Net Fellowship, the 2014 International Humanist Award and the 2015 Commonwealth Youth Award for Asia, Gulalai was named as one of Foreign Policy’s Global Thinkers in 2013 and has been featured by the BBC, Guardian, Huffington Post and more. -

National Human Development Report

Pakistan National Human Development Report Unleashing the Potential of a Young Pakistan The front cover of this report represents a vi- sual exercise depicting Pakistan’s youth as a 100 young people. Our wheel of many colours represents the multiple dimensions of what it means to be young in Pakistan today. Based on national data as well as results of our own sur- veys, the Wheel presents a collage of informa- tion on Pakistan’s young people (details in Chap- ter 2). This tapestry shows the diversity as well as vibrance of our youth, while also highlighting the inequities and hurdles they face as young Pakistanis. We chose the Wheel as this Report’s motif and cover art, because it represents not only the basis of our hopes for the future, but also our concerns. Diagram inspired by Jack Hagley’s ‘The world as100 people’. Pakistan National Human Development Report 2017* Unleashing the Potential of a Young Pakistan *NOTE: The data (including national statistics, survey results and consultations) in this report was mostly completed in 2016. Published for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Reports: In 1990, Dr. Mahbub ul Haq produced the first Human Develop- ment Report, introducing a new concept of human development focusing on expanding people’s opportunities and choices, and measuring a country’s development progress though the richness of human life rather than simply the wealth of its economy. The report featured a Human Devel- opment Index (HDI) created to assess the people’s capabilities. The HDI measures achievements in key dimensions of human development: individuals enabled to live long and healthy lives, to be knowledgeable, and have a decent standard of living. -

Sb List for 22-03-2019(Friday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 22 MARCH, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 1. W.P 4354/2018() Jan Raheem and Others Mohib Jan Salarzai V/s Sardar Khan and Others AG KPK 2. W.P 4914/2018 Dr. Naiz Ahmed Muhammad Farooq Afridi With IR,() V/s FCR Tribunal Through Its AG KPK Chairman 3. W.P 6050/2018 Ghulam Said Fida Gul With IR,() V/s Rashid AG KPK 4. W.P 945/2019 Ghulam Hussain Khanzada Ajmal Zeb Khan With IR() V/s Commissioner FCR Kohat Writ Petition Branch AG Office Division 5. W.P 978/2019() Kaleem Ullah Abdur Rauf Afridi V/s Government of KPK Writ Petition Branch AG Office 6. W.P 1107/2019 Ibna Amin Mian Afrasiab Gul Kakakhel with o/n() V/s Deputy Commissioner, District Writ Petition Branch AG Office Bajour MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 73 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 22 MARCH, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 7. W.P 1226/2019 Amjad Himayat Ullah With IR() V/s The State Writ Petition Branch AG Office 8. W.P 1509/2019 Ismail Muhammad Arif Jan With IR() V/s Assistant Commissioner Central Writ Petition Branch AG Office Kurram 9. W.P 1770/2019 Kandi Qasim Khel Fida Gul With IR() V/s Commissioner Kohat Writ Petition Branch AG Office 10. Cr.M/Q 10/2019() Feroze Muhammad Ismail Mohmand V/s The State Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 11. -

Editorials for the Month of February 2019

Editorials for the Month of February 2019 Note: This is a complied work by the Team The CSS Point. The DAWN.COM is the owner of the content available in the document. This document is compiled to support css aspirants and This document is NOT FOR SALE. You may order this booklet and only printing and shipping cost will be incurred. Complied & Edited By Shahbaz Shakeel (Online Content Manager) www.thecsspoint.com BUY CSS BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN https://cssbooks.net ALL COMPULSORY AND OPTIONAL SUBJECTS BOOK FROM SINGLE POINT ORDER NOW 03336042057 - 0726540141 DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540316 CSS PMS Current Affairs 2019 Edition By Ahmed Saeed Butt For Order Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Buy Latest Books Online as Cash on Delivery All Over Pakistan Call/SMS 03336042057 - 072654011 February 2019 Contents Monetary policy statement ........................................................................................................................ 10 Two new provinces .................................................................................................................................... -

Islamabad Peace Exchange – Organisations Attending

ISLAMABAD PEACE EXCHANGE – ORGANISATIONS ATTENDING The Islamabad Peace Exchange aims to bring together a diverse group of civil society organisations from across Pakistan, all of whom share a strong commitment to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. We hope that each participant will bring different experiences and contexts to share, as well as common lessons from their day to day operations. The event will be jointly hosted by the British Council in Pakistan, and the British charity, Peace Direct. Below is a list of the organisations who will be attending. For more information contact John Bainbridge: [email protected] Organisation: Association for Behaviour and Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) Representative: Ms. Shad Begum, Executive Director Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] ; [email protected] The Association for Behaviour & Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) is an organisation of leading social entrepreneurs from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Founded in 1994, it is a nationally recognised NGO that strives to improve the lives of underdeveloped and vulnerable communities, with a special focus on women, youth and children in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. ABKT is currently mobilising and linking young people from across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to ensure their effective and constructive contribution to peace in the region. ABKT has organised many peacebuilding events, such as the Peace and Development Seminar in October 2010, and the District Level Forum on Peace in 2010. Organisation: Aware Girls Representative: Ms. Gulalai Ismail, Chairperson Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] Aware Girls seeks to enable young people from the Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa Province and Tribal Area of Pakistan to develop the leadership and peer-education skills necessary for promoting peace and non-violence in the region.