Introductions to Heritage Assets: Stone Castles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

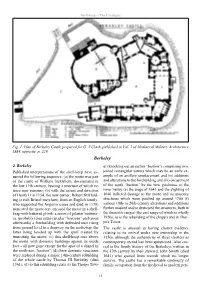

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

The Castle Studies Group Bulletin

THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP BULLETIN Volume 21 April 2016 Enhancements to the CSG website for 2016 INSIDE THIS ISSUE The CSG website’s ‘Research’ tab is receiving a make-over. This includes two new pages in addition to the well-received ‘Shell-keeps’ page added late last News England year. First, there now is a section 2-5 dealing with ‘Antiquarian Image Resources’. This pulls into one News Europe/World hypertext-based listing a collection 6-8 of museums, galleries, rare print vendors and other online facilities The Round Mounds to enable members to find, in Project one place, a comprehensive view 8 of all known antiquarian prints, engravings, sketches and paintings of named castles throughout the News Wales UK. Many can be enlarged on screen 9-10 and downloaded, and freely used in non-commercial, educational material, provided suitable credits are given, SMA Conference permissions sought and copyright sources acknowledged. The second page Report deals with ‘Early Photographic Resources’. This likewise brings together 10 all known sources and online archives of early Victorian photographic material from the 1840s starting with W H Fox Talbot through to the early Obituary 20th century. It details the early pioneers and locates where the earliest 11 photographic images of castles can be found. There is a downloadable fourteen-page essay entitled ‘Castle Studies and the Early Use of the CSG Conference Camera 1840-1914’. This charts the use of photographs in early castle- Report related publications and how the presentation and technology changed over 12 the years. It includes a bibliography and a list of resources. -

Durham Dales Map

Durham Dales Map Boundary of North Pennines A68 Area of Outstanding Natural Barleyhill Derwent Reservoir Newcastle Airport Beauty Shotley northumberland To Hexham Pennine Way Pow Hill BridgeConsett Country Park Weardale Way Blanchland Edmundbyers A692 Teesdale Way Castleside A691 Templetown C2C (Sea to Sea) Cycle Route Lanchester Muggleswick W2W (Walney to Wear) Cycle Killhope, C2C Cycle Route B6278 Route The North of Vale of Weardale Railway England Lead Allenheads Rookhope Waskerley Reservoir A68 Mining Museum Roads A689 HedleyhopeDurham Fell weardale Rivers To M6 Penrith The Durham North Nature Reserve Dales Centre Pennines Durham City Places of Interest Cowshill Weardale Way Tunstall AONB To A690 Durham City Place Names Wearhead Ireshopeburn Stanhope Reservoir Burnhope Reservoir Tow Law A690 Visitor Information Points Westgate Wolsingham Durham Weardale Museum Eastgate A689 Train S St. John’s Frosterley & High House Chapel Chapel Crook B6277 north pennines area of outstanding natural beauty Durham Dales Willington Fir Tree Langdon Beck Ettersgill Redford Cow Green Reservoir teesdale Hamsterley Forest in Teesdale Forest High Force A68 B6278 Hamsterley Cauldron Snout Gibson’s Cave BishopAuckland Teesdale Way NewbigginBowlees Visitor Centre Witton-le-Wear AucklandCastle Low Force Pennine Moor House Woodland ButterknowleWest Auckland Way National Nature Lynesack B6282 Reserve Eggleston Hall Evenwood Middleton-in-Teesdale Gardens Cockfield Fell Mickleton A688 W2W Cycle Route Grassholme Reservoir Raby Castle A68 Romaldkirk B6279 Grassholme Selset Reservoir Staindrop Ingleton tees Hannah’s The B6276 Hury Hury Reservoir Bowes Meadow Streatlam Headlam valley Cotherstone Museum cumbria North Balderhead Stainton RiverGainford Tees Lartington Stainmore Reservoir Blackton A67 Reservoir Barnard Castle Darlington A67 Egglestone Abbey Thorpe Farm Centre Bowes Castle A66 Greta Bridge To A1 Scotch Corner A688 Rokeby To Brough Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2015. -

Yorkshire Painted and Described

Yorkshire Painted And Described Gordon Home Project Gutenberg's Yorkshire Painted And Described, by Gordon Home This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Yorkshire Painted And Described Author: Gordon Home Release Date: August 13, 2004 [EBook #9973] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Michael Lockey and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED BY GORDON HOME Contents CHAPTER I ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY CHAPTER II ALONG THE ESK VALLEY CHAPTER III THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR CHAPTER IV THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER V Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER VI WHITBY CHAPTER VII THE CLEVELAND HILLS CHAPTER VIII GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY CHAPTER IX FROM PICKERING TO RIEVAULX ABBEY CHAPTER X DESCRIBES THE DALE COUNTRY AS A WHOLE CHAPTER XI RICHMOND CHAPTER XII SWALEDALE CHAPTER XIII WENSLEYDALE CHAPTER XIV RIPON AND FOUNTAINS ABBEY CHAPTER XV KNARESBOROUGH AND HARROGATE CHAPTER XVI WHARFEDALE CHAPTER XVII SKIPTON, MALHAM AND GORDALE CHAPTER XVIII SETTLE AND THE INGLETON FELLS CHAPTER XIX CONCERNING THE WOLDS CHAPTER XX FROM FILEY TO SPURN HEAD CHAPTER XXI BEVERLEY CHAPTER XXII ALONG THE HUMBER CHAPTER XXIII THE DERWENT AND THE HOWARDIAN HILLS CHAPTER XXIV A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE CITY OF YORK CHAPTER XXV THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICT INDEX List of Illustrations 1. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

Medieval Castle

The Language of Autbority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle M. Justin McGrail Deparment of Art History McGilI University Montréal March 1995 "A rhesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fu[filment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Am" O M. Justin McGrail. 1995 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*u of Canada du Canada Aquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellingîon Street 395, nie Wellingtm ûîtawaON K1AON4 OitawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papet or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. H. J. B6ker for his perserverance and guidance in the preparation and completion of this thesis. I would also like to recognise the tremendous support given by my family and friends over the course of this degree. -

Charles I: the Court at War

6TH NOVEMBER 2019 Theatres of Revolution: the Stuart Kings and the Architecture of Disruption – Charles I: The Court at War PROFESSOR SIMON THURLEY In my last lecture I described what happened when through choice or catastrophe a monarch cannot rule or live in the palaces and places designed for it. King James I subverted English courtly conventions and established a series of unusual royal residences that gave him privacy and freedom from conventional royal etiquette. Although court protocol prevailed at Royston, there was none of the grandeur that the Tudor monarchs would have expected. Indeed, from our perspective Royston was not a palace at all, just a jumble of houses in a market town. Today we turn our attention to King Charles I. In a completely different way from his father he too ended up living in places which we would hesitate to call palaces. But the difference was that he strove at every turn to maintain the magnificence and dignity due to him as sovereign. On 22 August 1642 King Charles raised his standard at Nottingham signalling the end of a stand-off with Parliament and the beginning of what became Civil War. Since the 10th January, when Charles had abandoned London, after his botched attempt to arrest five members of parliament, he had been on the move. Hastily exiting from Whitehall, he arrived late at Hampton Court which was quite unprepared to receive the royal family; it was cold and only partially furnished when Charles entered his privy lodgings. But the king’s main concern was security, not comfort, and preparations were undertaken at lightning speed for the king and queen to move to the safety of Windsor Castle. -

TEESDALE MERCURY—WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 24, Is;E. M ISC EL LAN Tj from GENOA It Is Reported That a Strict ENGLAND HAS DECLINED to Join in the Austro- JKJTHB BAI-ON F

TEESDALE MERCURY—WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 24, is;e. M ISC EL LAN tJ FROM GENOA it is reported that a strict ENGLAND HAS DECLINED to join in the Austro- JKJTHB BAI-ON F. TON DiEiiGARDr has given the and the military and poli-e wer; BOapellid to watch is being kept over Garibaldi's movements. Italian League for the restoration of peace, whioh munificent donation of X10.000 to the committee of interfere. HEAVY COMPENSATION FOR A RAII At Caprera a Government Bteamer is continually in had been proposed by Count von Beast. The league the German Hospital at Dalston, for the purposes of At tbe late Manchester Assi| TdE CBINESE MISSION, which is A SPECIAL SITTING OF STIPENDIARY MAG I >T.til l;, sight, and all communication between the two neigh was intended to protect both France and Germany the charity. A special general court of the governors was held at Derry on Saturday evening, for the in>. graves, commercial traveller, bp Madrid, 13 causing much curiosity. bouring islands of Caprera and La Madeleine is for from any I033 of territory; but, in oaseof the defeat has been called for Friday next for the purpose of mediate trial of the parties implicated in the .lots of against tbe Lancashire and Yorktl FOOTPRINTS ON THE SANDS OP TIME Crows' bidden without special permit. of Prussia, it would not have prevented the dissolu giving the committee power to invest the money. the 12th. Several of the rioters were sent to gaol injuries sustained in a oollition - feet —Fit*. I ON FRIDAY the new act to shorten the time tion of the North Gorman Confederation. -

MEDIEVAL STONE WINDOW TRACERY This Fragment of Window Tracery (Ornamental Stonework) Is Made from Sandstone

SOURCE 2 MEDIEVAL STONE WINDOW TRACERY This fragment of window tracery (ornamental stonework) is made from sandstone. It filled the space over an arch. It is kept in our archaeological store at Wrest Park. This dragon carving is probably from the 13th century. William de Valence took ownership of Goodrich Castle in 1247, on his marriage to Joan, the heiress of William Marshal 1st earl of Pembroke. The coat of arms of the Earls of Pembroke was the red dragon. SOURCE 3 ‘Item 10 shillings 6 pence in procuring 3 carts to transport the mistress’s property by road. Item 6 pence for a horse to carry the mistress’s money by road. Item 2 shillings, 5 pence for 8 horses and 4 carters, loaned by abbot of Gloucester and the abbot of Nutley for transporting the mistress’s property by road, staying a night across the river Wye, unable to get across. Item 3 shillings and 6 pence for the 4-horse cart of the abbot of Nutley, taking 3 days to return from Goodrich Castle to Nutley… Item 16 pence to John the baker for 8 days travelling from Exning to Goodrich Castle to bake bread there before the mistress’s arrival… 1 penny for a lock for the door of the building where the horses’ feed is kept. 6 pence for buying a storm lantern for the kitchen window. 4 pounds, 5 shillings and 6 pence for 114 pounds of wax bought at Monmouth… 8 pence for making surplices for the mistress’s chapel, 18 pence to the chaplain for making wax tapers for the chapel.