Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monkey's Tale

A Monkey’s Tale P.T. Barnum - a most remarkable showman There were also living exhibits at his Ameri- in 19th century America began his career can Museum. Barnum exhibited a four-year- long before his famous circus was created old boy who stood 25 inches high. This boy in 1872. In January 1842, Barnum opened famously became known as General Tom his American Museum in New York. The Thumb, or Man in Miniature, who Barnum Museum was promoted as a place for billed as an eleven-year-old. New York was family entertainment, enlightenment and fascinated by Tom Thumb and his popular- amusement. ity encouraged Barnum to arrange a tour around England where the company was From 1842 until 1865, the American Museum given an audience of Queen Victoria, the grew into an enormous enterprise. Barnum’s royal family and many heads of states. cryptozoology department in particular gained a lot of attention, from when he introduced his first major hoax: a creature with the head of a monkey and the tail of a fish, known as the “Feejee” mermaid. The Museum also contained a wax-figure department which produced likenesses of notable personalities of the day, an aquarium and a taxidermy department. A Monkey’s Tale The circus which P.T. Barnum is famous for Barnum’s Mandrill was his retirement project. Barnum was already a well-established entertainer but Barnum and Bailey’s Circus travelled in four at 61 years old he began the “Greatest trains of 15 coaches, with most of the car- Show on Earth”. -

Barnum Museum, Planning to Digitize the Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/humanities-collections-and-reference- resources for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for "The Greatest Digitization Project on Earth" with the P. T. Barnum Collections of The Barnum Museum Foundation Institution: Barnum Museum Project Director: Adrienne Saint Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Barnum Museum Foundation, Inc. Application to the NEH/Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Program Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. -

Barnum Institute of Science and History" in Low Relief

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) &ifiif *y tfvtft. pillllii^ COMMON: r^<~~~~ r. , ~T~~~^ Barnum Museum /" ^, -v/\ AND/OR HISTORIC: /fc fttffiNftJ "'^ Barnum. .Institute of s.$-ienp,<? a.nr) History iffifoxv STREET AND NUMBER: ICO'. \ P Rn^ MATTI Street CITY OR TOWN: X%; ^^\^' Brido-fipnrt STATE CODE COUNTY: ^^J 1 I'f'^ \-^ CODE Connecti cut DQ T?n la^isld,,,.,.....,,,,............,. , ,,,,001...... li!l|$pli;!!iieil::!!::!!l!;;! STATUS ACCESSIBLE <c"«o™ ™«t™" TO THE PUBLIC G District 22 Building El Public Public Acquisition: BQ Occupied Yes: ,, . El Restricted G Site G Structure d Private G In Process D Unoccupied *Qsl i in . G Unrestricted G Object D Botn D Being Considerec G Preservation work in progress ' ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) G Agricultural G Government G Park 1 | Transportation 1 1 Comments G Commercial G Industrial G Private Residence n Other (Soecify) G Educational G Military G Religious 1 I Entertainment 53 Museum | | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: STATE: City of Bridgeport STREET AND NUMBER: Connecticut CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE: CODE ill .....Bridgeport C onnecticut O<9 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: Citv Hal 1 STREET AND NUMBER: ^airfield It 1} T.yon Terrace CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE CODE Rridsre-nort p..7T)7iftCtPiffiTh OQ llltl!!!!^ TITUE OF SURVEY: a NUMBERENTRY Connecticut Historic Structures and Landmarks Survey Tl DATE OF SURVEY: -| Q££ r~j Federal Qfl State "G County G L°ca O 73 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Z TO CO CO Connecticut. -

Jenny Lind's Visit to Elizabethtown, April 1851

Jenny Lind’s visit to Elizabethtown, April 1851 Jenny Lind, the Swedish soprano, entertained the townspeople of Elizabethtown during a tour of the United States in April 1851. She had come to United States in September 1850, under a contract with P.T. Barnum to give 150 concerts for $1,000 dollars each. Jenny Lind, or the "Swedish nightingale," as she was known benefited from Barnum's skillful publicity that brought ex- cited crowds flocking to her concerts, and Lind's name was eventually tied to every kind of commodity, from songs to gloves, bonnets, chairs, sofas, and even pianos. Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891), or P.T. Barnum as he was known is one of the most colorful and well known per- sonalities in American history. A consummate showman and entrepreneur, Barnum was famous for bringing both high and low culture to all of America. From the dulcet tones of opera singer Jenny Lind to the bizarre hoax of the Feejee Mermaid, from the clever and quite diminutive General Tom Thumb to Jumbo the Elephant, Barnum's oddities, Barnum in 1851, just spectacles, galas, extravaganzas, and events tickled the before he went on tour fancies, hearts, minds and imaginations of Americans of all with Jenny Lind. ages. On April 4, 1851, after giving a concert in Nashville, Ms. Lind embarked by stagecoach on her journey to Louisville. The trip over the Louisville and Nashville Turnpike required three days. During the trip, while horses were being changed and during overnight stops, she graciously enter- tained the local residents. The night of April 4th was spent at Bell’s Tavern (now Park City). -

Animal Metropolis: Histories of Human-Animal Relations in Urban Canada

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-02 Animal Metropolis: Histories of Human-Animal Relations in Urban Canada Dean, Joanna; Ingram, Darcy; Sethna, Christabelle University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51826 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca ANIMAL METROPOLIS: HISTORIES OF HUMAN- ANIMAL RELATIONS IN URBAN CANADA Edited by Joanna Dean, Darcy Ingram, and Christabelle Sethna ISBN 978-1-55238-865-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Museum Archivist

Newsletter of the Museum Archives Section Museum Archivist Winter 2019 Volume 29, Issue 1 Letter From the Chair, Hillary Bober Dear Museum Archivists: sponse, and given up on the whole practice, or seen it happen to other posters and decided not to bother – also very understand- Crickets… in the metaphorical sense of silence. This has been able; what the MAS listserv has been lately. As long as I have been on 4.) We all know exactly what we are doing and have no the listserv, over 15 years in its two iterations, I have never been questions – the best possibility, but perhaps least likely? overwhelmed by messages. More recently though, aside from announcements, there have been only a handful of questions So, I am going to try to create some discussion. Each month I posed, at most, with little on-list discussion following. I can think will pose a question on the listserv, a broad topic about which of a number of potential reasons: we can share general thoughts, what we do, have done, would like to do, and why. These won’t be about official policies or 1.) We’re all busy, both professionally and personally, guidelines, such as the documents shared by the group and are and professional communication falls off the radar – something I available in the Standards and Best Practices Resource Guide, myself am guilty of; but more anecdotal in nature. I will promise, of course, to an- swer my own question by sharing what I do at the Dallas Muse- 2.) People hate listservs and are using social media for um of Art Archives. -

Boston Globe; the Tour Led from the Coliseum Grounds on Huntington Ave., to Boylston, Charles and Cambridge Streets Stopping in Bowdoin Square Before Continuing On

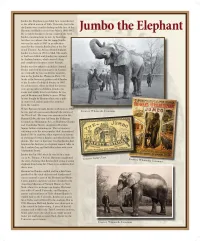

J umbo the Elephant is probably best remembered as the official mascot of Tufts University, but in his day Jumbo was a media darling and the face of the Barnum and Bailey circus from March 1882-1885. Jumbothe Elephant He is widely thought to be the origin of the word J umbo, meaning large in size, by historians, but there is evidence that the name Jumbo was used as early as 1847 in an advertise ment for the comedy Jwnbo]um at the Na tional Th eatre. An African Bush Elephant, J umbo was born in 1861 in Mali. His moth er had been killed and J umbo was captured by Arabian hunters, which started a long and complicated journey across Europe. Jumbo was first taken to an Italian Animal Dealer and then to a menagerie in Genna ny, eventually he was installed as an attrac tion in the.Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Of ficials at the botanical garden traded Jumb o to the London Zoological Society in 1865 for a rhinoceros, where he lived for sixteen years giving rides to children. Jumbo was iconic and widely loved even before he was part of Barnum and Bailey's circus. When he was bought by Barnum there was a pub lic outcry in London against his removal from the country. When Barnum brought Jumbo to Boston in 1882, he was part of a procession through the streets of Courtesy Wikimedia Commons the West End. His route ·wasannounced in the Boston Globe; the tour led from the Coliseum Grounds on Huntington Ave., to Boylston, Charles and Cambridge Streets stopping in Bowdoin Square before continuing on. -

Appendix I P. T. Barnum: Humbug and Reality

APPENDIX I P. T. BARNUM: HUMBUG AND REALITY s a candidate for the father of American show business, Barnum’s Awider significance is still being quarried by those with an interest in social and cultural history. The preceding chapters have shown how vari- ety, animal exhibits, circus acts, minstrelsy, and especially freak shows, owe much of their subsequent momentum to his popularization of these amusement forms. For, while Barnum has long been associated in popular memory solely with the circus business, his overall career as an entertainment promoter embraced far more than the celebrated ringmas- ter figure of present-day public estimation. Barnum saw himself as “the museum man” for the better part of his long show business career, following his successful management of the American Museum from the 1840s to the 1860s. To repeat, for all Barnum’s reputation today as a “circus man,” he saw himself first and foremost as a museum proprietor, one who did much to promote and legitimize the display of “human curiosities.”1 While the emergence of an “American” national consciousness has been dated to the third quarter of the eighteenth century, Barnum’s self- presentation was central to the cultural formation of a particular middle- class American sense of identity in the second half of the nineteenth century (see chapter 1), as well as helping to shape the new show business ethos. Over time, he also became an iconic or referential figure in the wider culture, with multiple representations in cinematic, theatrical, and literary form (see below).Yet was Barnum really the cultural pacesetter as he is often presented in popular biographical writing, not to mention his own self-aggrandizing prose. -

Guide to the P.T. Barnum Collection, 1866-1890

Guide to the P.T. Barnum Collection, 1866-1890 NMAH.AC.0068 Robert S. Harding 1983 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 P.T. Barnum Collection NMAH.AC.0068 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: P.T. Barnum Collection Identifier: NMAH.AC.0068 Date: 1866-1890 Creator: Barnum, P. T. (Phineas Taylor), 1810-1891 Extent: 0.5 Cubic feet Language: English . Summary: The collection consists of five children's books about the circus, a brochure announcing the show in London, an 1873 advertisement for the Great Traveling World's Fair of Barnum's, and two scrapbooks. Administrative Information Acquisition -

Barnum Museum, Digitizing the P.T. Barnum Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/divisions/preservation for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Creating the P.T. Barnum Digital Collection Institution: Barnum Museum Foundation Inc. Project Director: Adrienne Saint-Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 400 7th Street, SW, Floor 4, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 1. Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. An American icon whose name is still recognized around the world, P.T. Barnum was born in Bethel, Connecticut, in 1810. -

Guide to the PT Barnum Research Collection

Guide to the P.T. Barnum Research Collection (BHC-MS 0001) By Meghan Rinn January 2017 Descriptive Summary Creator: P.T. Barnum; Nancy Fish; Jenny Lind; Charles S. Stratton; M. Lavinia Warren; others Title: P.T. Barnum Research Collection Dates: 1735-1988 [bulk 1830-1921] Quantity: 18 manuscript boxes, 10 oversize drawers Abstract: The P.T. Barnum Research Collection represents archival materials collected by the Bridgeport History Center over the years relating to the life and ventures of P.T. Barnum. Barnum himself was deeply connected to Bridgeport, building four homes there, serving as mayor, and hosting his circus' Winter Quarters in the city. As a result, this collection represents both national and local history. The series in the collection relate to his personal life, the American Museum, Barnum's circus ventures, Jumbo the Elephant, Jenny Lind, and Charles S. Stratton and Lavinia Warren. Each series contains manuscript material including an extensive correspondence series in Barnum’s own hand, programs, tickets, artifacts, illustrations, and photographs, as well as clippings and examples of promotional material in the form of booklets, trading cards, and even paper dolls. This collection is artificial, and has grown over the years. The series themselves were formed by researcher needs, and as such have been kept intact at the time of arrangement. Collection Number: BHC-MS 0001 Language: English Repository: Bridgeport History Center Biographical Information or Administrative History P.T. Barnum Phineas Taylor (P. T.) Barnum was born in Bethel, Connecticut on 5 July, 1810. Barnum’s name is popularly associated with the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth, but the circus was only one facet of his career. -

Jumbo's Long Journey to Tufts

MEDFORD HISTORICAL SOCIETY & MUSEUM WINTER, 2018 President’s Overview Jumbo’s Long Journey to Tufts by John Anderson by Nancy White I’d like to recognize the generous donation Jumbo travelled of time and the accomplishments of our with P.T. Barnum’s circus for many volunteers in 2017. I personally enjoyed years before he ALL the programs and newsletters this year. was tragically Newsletter highlights for me included an killed in a collision article about West Medford and one noting with a train in the connection between the Brooks family Ontario in 1885. and Chicago architecture. Thanks to our hardworking Program Committee, we’ve enjoyed a variety of events throughout the year. For me, all all events in the WWI series on the Medford-Malden historic football rivalry were special hits. This year’s holiday party/lecture earned rave reviews! Behind the scenes, volunteers have created new work spaces by cleaning out Somewhere between the years of hay, one barrel of potatoes, items such as broken vacuums, outdated 1859-1860, a male elephant was two bushels of oats, 15 loaves computer equipment and excess furniture. born in the French Sudan Terri- of bread, a slew of onions, and They’ve also been furiously inventorying tory of Africa. The name given to several pails of water. When collections, entering info into our comput- this baby elephant was Jumbe, Jumbo was not feeling well, it was er database, researching items’ provenance a Swahili name meaning chief. reported that Scott gave Jumbo and relevance to Medford and our general When fully grown, he would be the two gallons of whiskey to drink.