Local and Regional Democracy in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

Israeli Settlement in the Occupied Territories

REPORT ON ISRAELI SETTLEMENT IN THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES A Bimonthly Publication of the Foundation for Middle East Peace Volume 20 Number 4 July-August 2010 MOVING BEYOND A SETTLEMENT FREEZE — THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION LOOKS FOR A NEW COURSE By Geoffrey Aronson the settlement of Amona, for example, The wave of building in Judea the state prosecutor’s office offered an In their meeting on July 6, President and Samaria has never been explanation for its inaction that was Barack Obama and Israeli prime minis- higher. Thousands of units are described by Ha’aretz correspondent ter Benjamin Netanyahu presented a being built in every location. I Akiva Eldar as “the line that will go well-choreographed bit of political the- was never a fan of the freeze. No down in the ‘chutzpah’ record books: atre aimed at highlighting the “excel- one in the cabinet was. [The The prosecution asks to reject the lent” personal and political relations be- freeze] was a mistake. It is impos- demand to evacuate the illegal settle- tween the two leaders and the countries sible to take people and freeze ment since diverting the limited means they represent. Obama explained after them. This is not a solution. The of enforcement to old illegal construc- their meeting that, “As Prime Minister government remains committed tion ‘is not high on the respondents’ Netanyahu indicated in his speech, the to renew a wave of construction agenda.’ And why not? ‘Means of bond between the United States and this coming September. In any enforcement’ are needed to implement Israel is unbreakable. -

Health in Italy in the 21St Century

FOREWORD Rosy Bindi Minister of Health of Italy Roma, September 1999 This report provides the international community with an overall assessment of the state of health in Italy, as well as with the main developments of the Italian public health policy expected in the near future. It is intended as an important contribution towards the activities which, beginning with the 49th WHO Regional Committee in Florence, will be carried out in Europe with a view to defining health policies and strategies for the new century. This publication, which consists of two sections, illustrates the remarkable health achievements of Italy as regards both the control of diseases and their determinants, and the health care services. Overall, a clearly positive picture emerges, which is due not only to the environmental and cultural characteristics of Italy, but also to its health protection and care system which Italy intends to keep and indeed to improve in the interest of its citizens. The recent decisions taken in the framework of the reform of the National Health System in Italy intend to improve and strengthen the model of a universal health system based on equity and solidarity, which considers health as a fundamental human right irrespective of the economic, social and cultural conditions of each citizen. The new national health service guarantees, through its public resources, equal opportunities for accessing health services as well as homogenous and essential levels of health care throughout the country. Such a reorganization of the system has become necessary in order to meet new and growing demands for health within the framework of limited resources and with the understanding that equity in health is not only an ethical requirement, but also a rational and efficient way for allocating resources. -

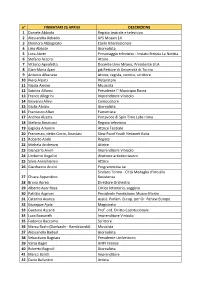

Firmatari Appello 25Aprile.Pdf

n° FIRMATARI 25 APRILE DESCRIZIONE 1 Daniele Abbado Regista teatrale e televisivo 2 Alessandra Abbado APS Mozart 14 3 Eleonora Abbagnato Etoile Internazionale 4 Lirio Abbate Giornalista 5 Luca Abete Personaggio televisivo - Inviato Striscia La Notizia 6 Stefano Accorsi Attore 7 Vittorio Agnoletto Docente Univ Milano, Presidente LILA 8 Gian Maria Ajani già Rettore di Università di Torino 9 Antonio Albanese Attore, regista, comico, scrittore 10 Piero Alciati Ristoratore 11 Nicola Alesini Musicista 12 Sabrina Alfonsi Presidente I° Municipio Roma 13 Franco Allegrini Imprenditore Vinicolo 14 Giovanni Allevi Compositore 15 Giulia Aloisio Giornalista 16 Francesco Altan Fumettista 17 Andrea Alzetta Portavoce di Spin Time Labs roma 18 Stefano Amatucci Regista televisivo 19 Gigliola Amonini Attrice Teatrale 20 Francesco, detto Ciccio, Anastasi Slow Food Youth Network Italia 21 Roberto Andò Regista 22 Michela Andreozzi Attrice 23 Giancarlo Aneri Imprenditore Vinicolo 24 Umberto Angelini direttore artistico teatro 25 Silvia Annichiarico Attrice 26 Gianfranco Anzini Programmista rai Sindaco Torino - Città Medaglia d'oro alla 27 Chiara Appendino Resistenza 28 Bruno Aprea Direttore Orchestra 29 Alberto Asor Rosa Critico letterario, saggista 30 Patrizia Asproni Presidente Fondazione Museo Marini 31 Caterina Avanza Assist. Parlam. Europ. per Gr. Renew Europe 32 Giuseppe Ajala Magistrato 33 Gaetano Azzariti Prof. ord. Diritto Costituzionale 34 Luca Baccarelli Imprenditore Vinicolo 35 Federico Baccomo Scrittore 36 Marco Bachi (Donbachi - Bandabardò) Musicista -

![Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6369/italian-repubblica-italiana-7-8-9-10-is-a-unitary-parliamentary-republic-insouthern-europe-356369.webp)

Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe

Italy ( i/ˈɪtəli/; Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja]), officially the Italian Republic (Italian: Repubblica italiana),[7][8][9][10] is a unitary parliamentary republic inSouthern Europe. Italy covers an area of 301,338 km2 (116,347 sq mi) and has a largely temperate climate; due to its shape, it is often referred to in Italy as lo Stivale (the Boot).[11][12] With 61 million inhabitants, it is the 5th most populous country in Europe. Italy is a very highly developed country[13]and has the third largest economy in the Eurozone and the eighth-largest in the world.[14] Since ancient times, Etruscan, Magna Graecia and other cultures have flourished in the territory of present-day Italy, being eventually absorbed byRome, that has for centuries remained the leading political and religious centre of Western civilisation, capital of the Roman Empire and Christianity. During the Dark Ages, the Italian Peninsula faced calamitous invasions by barbarian tribes, but beginning around the 11th century, numerous Italian city-states rose to great prosperity through shipping, commerce and banking (indeed, modern capitalism has its roots in Medieval Italy).[15] Especially duringThe Renaissance, Italian culture thrived, producing scholars, artists, and polymaths such as Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Michelangelo and Machiavelli. Italian explorers such as Polo, Columbus, Vespucci, and Verrazzano discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. Nevertheless, Italy would remain fragmented into many warring states for the rest of the Middle Ages, subsequently falling prey to larger European powers such as France, Spain, and later Austria. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/23/2021 12:29:26PM Via Free Access Austria Belgium

Section 5 Data relating to political systems THE COUNTRIES OF WESTERN EUROPE referendum. The constitutional court (Verfassungsgerichtshof ) determines the constitutionality of legislation and Austria executive acts. Population 8.1 million (2000) Current government The 1999 Capital Vienna election brought to an end the Territory 83,857 sq. km 13-year government coalition GDP per capita US$25,788 (2000) between the Social Democratic Party Unemployment 3.7 per cent of of Austria (SPÖ) and Austrian workforce (2000) People’s Party (ÖVP), which had State form Republic. The Austrian been under considerable strain. When constitution of 1920, as amended in the two parties failed to reach a 1929, was restored on 1 May 1945. On coalition agreement, Austria found 15 May 1955, the four Allied Powers itself short of viable alternatives. The signed the State Treaty with Austria, record gains of the radical right ending the occupation and Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) had recognising Austrian independence. changed the balance of power within Current head of state President the party system. The other two Thomas Klestil (took office 8 July numerically viable coalitions – 1992, re-elected 1998). SPÖ/FPÖ or ÖVP/FPÖ – had been State structure A federation with nine ruled out in advance by the two provinces (Länder), each with its own mainstream parties. An attempt by the constitution, legislature and SPÖ to form a minority government government. failed. Finally, a coalition was formed Government The president appoints the between the ÖVP and FPÖ under prime minister (chancellor), and, on Wolfgang Schüssel (ÖVP) and the chancellor’s recommendation, a reluctantly sworn in by President cabinet (Council of Ministers) of Klestil on 5 February 2000. -

Framing “The Gypsy Problem”: Populist Electoral Use of Romaphobia in Italy (2014–2019)

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Framing “The Gypsy Problem”: Populist Electoral Use of Romaphobia in Italy (2014–2019) Laura Cervi * and Santiago Tejedor Department of Journalism and Communication Sciences, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Campus de la UAB, Plaça Cívica, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 17 June 2020 Abstract: Xenophobic arguments have long been at the center of the political discourse of the Lega party in Italy, nonetheless Matteo Salvini, the new leader, capitalizing on diffused Romaphobia, placed Roma people at the center of his political discourse, institutionalizing the “Camp visit” as an electoral event. Through the analysis of eight consecutive electoral campaigns, in a six year period, mixing computer-based quantitative and qualitative content analysis and framing analysis, this study aims to display how Roma communities are portrayed in Matteo Salvini’s discourse. The study describes how “Gypsies” are framed as a threat to society and how the proposed solution—a bulldozer to raze all of the camps to the ground—is presented as the only option. The paper concludes that representing Roma as an “enemy” that “lives among us”, proves to be the ideal tool to strengthen the “us versus them” tension, characteristic of populist discourse. Keywords: populism; Romaphobia; far right parties; political discourse 1. Introduction Defining Roma is challenging. A variety of understandings and definitions, and multiple societal and political representations, exist about “who the Roma are” (Magazzini and Piemontese 2019). The Council of Europe, in an effort to harmonize the terminology used in its political documents, apply “Roma”—first chosen at the inaugural World Romani Congress held in London in 1971—as an umbrella term that includes “Roma, Sinti, Travellers, Ashkali, Manush, Jenische, Kaldaresh and Kalé” and covers the wide diversity of the groups concerned, “including persons who identify themselves as Gypsies” (2012). -

Roman Large-Scale Mapping in the Early Empire

13 · Roman Large-Scale Mapping in the Early Empire o. A. w. DILKE We have already emphasized that in the period of the A further stimulus to large-scale surveying and map early empire1 the Greek contribution to the theory and ping practice in the early empire was given by the land practice of small-scale mapping, culminating in the work reforms undertaken by the Flavians. In particular, a new of Ptolemy, largely overshadowed that of Rome. A dif outlook both on administration and on cartography ferent view must be taken of the history of large-scale came with the accession of Vespasian (T. Flavius Ves mapping. Here we can trace an analogous culmination pasianus, emperor A.D. 69-79). Born in the hilly country of the Roman bent for practical cartography. The foun north of Reate (Rieti), a man of varied and successful dations for a land surveying profession, as already noted, military experience, including the conquest of southern had been laid in the reign of Augustus. Its expansion Britain, he overcame his rivals in the fierce civil wars of had been occasioned by the vast program of colonization A.D. 69. The treasury had been depleted under Nero, carried out by the triumvirs and then by Augustus him and Vespasian was anxious to build up its assets. Fron self after the civil wars. Hyginus Gromaticus, author of tinus, who was a prominent senator throughout the Fla a surveying treatise in the Corpus Agrimensorum, tells vian period (A.D. 69-96), stresses the enrichment of the us that Augustus ordered that the coordinates of surveys treasury by selling to colonies lands known as subseciva. -

Barking Riverside, London First Options Testing of Options: Sketch (Neighborhood Scale)

CLIMATE-RESILIENT URBAN PLANS AND DESIGNS QUEZON CITY Tools for Design Development I - Urban Design as a Tool Planning Instruments •Philippine Development Plan / Regional Development Plan Comprehensive Plans, NEDA – National Economic and Development Authority •The Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) ~1:40 000 - 1: 20 000 strategic planning approach, specific proposals for guiding, regulating growth and development; considers all sectors significant in the development process consistent with and supportive of provincial plan provides guidelines for city/municipality, including •Zoning Ordinances (implementing tool of the CLUP) divides a territory into zones (residential, commercial, industrial, open space, etc) and specifies the nature and intensity of use of each zone. It is required to be updated every 5 years. •Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) Medium-term plan of action implementing the CLUP (3-6 years), covers the social, economic, infrastructure, environment and institutional sectors •Barangay Development Plan (BDP) socio-economic and physical plan of the barangay; includes priority programmes, projects and activities of the barangay development council enumerates specific programmes and projects and their costs; justifies the use of the Barangay’s share of the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) coming from the national government. Usually a list of projects. Urban Design “CityLife Masterplan” - Milano II - The Design Brief as Tool for Resilient Urban Design Instruments per Scale, New ZealandMetropolitan City-wide (urban area) Urban District PrivateNeighborhood Space Street Purpose of the Design Brief 1. The Task specifies what a project has to achieve, by what means, in what timeframe so the design team works towards the right direction (e.g. environmental targets, programme, demands for m²) 2. -

San Casciano Val Di Pesa, Province of Florence, Italy

Title of the experience : Community Mobility Network (Muoversi in Comune) Name of city/region : San Casciano Val di Pesa, Province of Florence, Italy Promoting entity: Promoted by the Municipality of San Casciano Val di Pesa (Italy) with the Support of the Regional Authority for Participation of the Region of Tuscany. Country: Italy Starting date: 03/2015 Finishing date : 07/2015 Name of the contact person: Leonardo Baldini Position of the contact person: Responsabile del servizio Cultura e Sport – Municipality of San Casciano Val di Pesa Contact telephone: E-mail: [email protected] +39 055 8256260 Population size: 17 201 (01-01-2015) Surface area: 107,83 km² Population Density: 159,52 ab./km² Collaborative service design in smart X Type of experience mobility Regional scope District X Thematic area Transportation X Accessibility, in the sense of the concrete and effective possibility of accessing the workplace, social services, health centers, educational spaces, but also cultural and recreational facilities is a fundamental component in the fight against social exclusion and a discriminating factor in the promotion of social well-being and quality of life. In this context, public and private transports can present high barriers to entry: timetables, routes and costs may preclude their use, especially among the most vulnerable and less autonomous sectors of the population. The City Council of San Casciano Val di Pesa (Italy) suffering in recent years from repeated cuts at the central and regional level to the financial resources needed to provide adequate public transportation, decided to share with its citizens not only the investment choices in new services but also to actively involve the local community and key stakeholders in the participatory design of an innovative integrated mobility network. -

Fiera Di Vicenza 11-13 Ottobre 2017

Main sponsor Fiera di Vicenza 11-13 Ottobre 2017 PROGRAMMA www.xxxivassemblea.anci.it Lorem ipsum ESPOSITORI 1 - SVT LIVELLO 1 LIVELLO 0 2 - DEDEM LIVELLO 1 LIVELLO 0 LIVELLO 0 3 - CAMERA DI COMMERCIO 4 - AIM L 5 - COMUNE DI VICENZA Sala 6 - PROVINCIA DI VICENZA Ancitel ANCITE 60 posti Sala 7 - REGIONE VENETO Sala 8 - ANCI VENETO Conai 9 - ENTERPRISE CONTACT GROUP AREA 10 - ITALGAS Sala RISTORO Sala CONAI 90 posti 11 - CASSA GEOMETRI IFEL 12 - COMUNICA ITALIA Sala IFEL 60 posti 13 - MAPEI Sala 14 - COLDIRETTI ANCI Sala 15 - ITALIA OGGI Comunicare ANCI COMUNICARE 16 - AXIANS SAIV Sala Sala 17 - SICUREZZA E AMBIENTE 63 64 65 18 - MOIGE Sala A 19 - PHILIP MORRIS Cdp CCESSO Sala CASSA DEPOSITI E PRESTITIE PRESTITI 60 posti 20 - UTILITALIA A ALLA SALA PLENARI 21 - SISCOM 55 56 58 22 - BFT 60 61 62 23 - ARAN 54 57 59 24 - MYRTHA POOLS 25 - BBS 26 - ENGIE 27 - MUNICIPIA GRUPPO ENGINEERING A 47 51 53 SalaÀLIA 28 - STUDIO STORTI t 46 ile Cittalia CCESSO CITT 50 Sala To 48 49 52 29 - CONI A ALLA SALA PLENARI 29bis - CNPI t oile 30 - MANUTENCOOP T 31 - VODAFONE 39 43 32 - GRAFICHE GASPARI 37 38 45 33 - INPS 40 41 42 44 34 - ANAS 35 - SOSE 36 - GEOPLAN 29 36BIS - GLOBAL POWER SERVICE bis 29 30 32 33 37 - MINISTERO SALUTE 28 31 34 35 36 36 38 - MINISTERO ISTRUZIONE bis 39 - MINISTERO AMBIENTE 40 - IREDEEM SMART 41 - TIM PIAZZA 42 - GI GROUP 43 - PROGETTI E SOLUZIONI 18 19 22 24 44 - CEV 27 45 - DIPARTIMENTO FUNZIONE PUBBLICA 17 20 21 23 25 26 46 - CONAI 47 - AGENZIA PER LA COESIONE TERRITORIALE 48 - MIBACT 10 12 14 15 Sala 49 - LADISA 11 50 - KMG -

Italy: "Foreign Tax Policies and Economic Growth"

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Foreign Tax Policies and Economic Growth Volume Author/Editor: NBER and The Brookings Institution Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-470-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/unkn66-1 Publication Date: 1966 Chapter Title: Italy: "Foreign Tax Policies and Economic Growth" Chapter Author: Francesco Forte Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c1543 Chapter pages in book: (p. 165 - 206) Italy FRANCESCO FORTE UNIVERSITY OF TURIN I. POSTWAR ECONOMIC GROWTH The postwar economic growth of Italy has been remarkable com- pared with that of other industrialized countries, as well as with that of most previous periods in Italian economic history. Between 1951 and 1962, Italy's national income increased at a rate of about 6 per cent per annum in current lire, and the country's growth rate both in real and in per capita terms was almost as high. Prices were relatively stable through 1961; wholesale prices did not change, while retail prices rose only moderately. Population rose by only 6.5 per cent from 1951 to 1961, mainly as a result of a continuous re- duction in the mortality rate, owing to better sanitary conditions, to social assistance, and to an improved standard of living. This high and steady growth rate combined with reasonably sta- ble prices may suggest that the growth process has been essentially sound and that it has been supported by a good tax system and fa- vorable tax policies. This is not so.