Switching Social Contexts: the Effects of Housing Mobility and School Choice Programs on Youth Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Research.Pdf (2.230Mb)

THE ATTAINMENT OF SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH ADOELCSENT GIRLS LIVING AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY IN A COMMUNITY-BASED PEDAGOGICAL SPACE KNOWN AS AUNTIE’S PLACE _______________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Learning, Teaching and Curriculum College of Education at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by ADRIAN CLIFTON Dr. Lenny Sanchez, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2016 © Copyright by Adrian Clifton 2016 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE ATTAINMENT OF SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH ADOELCSENT GIRLS LIVING AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY IN A COMMUNITY-BASED PEDAGOGICAL SPACE KNOWN AS AUNTIE’S PLACE presented by Adrian Clifton, a candidate for the degree of [doctor of philosophy, doctor of education of _____________________________________________________________________, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Lenny Sanchez Professor Ty-Ron Douglas Professor Treva Lindsey Professor Jill Ostrow SOCIAL CAPITAL ATTAINMENT WITH ADOLESCENTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY Dedication I would like to dedicate this body of work to my mother, Verna Laboy, whose constant belief in me facilitated this great accomplishment. Mom, thanks for believing that I could have the world. It is important to highlight my husband. Collectively we have achieved this great accomplishment. Thank you Herman for being my rock. To my brother and sisters: Nicole McGruder, LaShai Hamilton, Shawn Harris, who have been pillars of support during this process. To my son, Herman Clifton IV, and daughters, Amari, Serenity and Adrian, whose patience and unwavering support of their mother has been stoic. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:446 洋楽最新ヒット 放送日:2020/12/14~2020/12/20 「番組案内 (4時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/8:00~/12:00~/16:00~/20:00~/24:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■洋楽最新ヒット HOLY Justin Bieber feat. Chance The Rapper I Hope GABBY BARRETT LIFE GOES ON BTS POSITIONS Ariana Grande LEVITATING DUA LIPA feat. DABABY GO CRAZY CHRIS BROWN & YOUNG THUG More Than My Hometown Morgan Wallen Dakiti Bad Bunny & Jhay Cortez Mood 24kGoldn feat. Iann Dior WAP [Lyrics!] CARDI B feat. Megan Thee Stallion MONSTER SHAWN MENDES & JUSTIN BIEBER THEREFORE I AM BILLIE EILISH Lemonade Internet Money feat. Gunna, Don Toliver, NAV KINGS & QUEENS Ava Max BLINDING LIGHTS The Weeknd SAVAGE LOVE (Laxed-Siren Beat) JAWSH 685×Jason Derulo BEFORE YOU GO Lewis Capaldi FOR THE NIGHT Pop Smoke feat. Lil Baby & Dababy BE LIKE THAT Kane Brown feat. Swae Lee & Khalid BANG! AJR All I Want For Christmas Is You (恋人たちのクリスマス) MARIAH CAREY LONELY Justin Bieber & Benny Blanco WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES LAUGH NOW CRY LATER DRAKE feat. LIL DURK Love You Like I Used To RUSSELL DICKERSON Starting Over Chris Stapleton 7 SUMMERS Morgan Wallen DIAMONDS SAM SMITH FOREVER AFTER ALL LUKE COMBS BETTER TOGETHER LUKE COMBS WHATS POPPIN Jack Harlow ROCKSTAR DABABY feat. RODDY RICCH SAID SUM Moneybagg Yo ONE BEER HARDY feat. Lauren Alaina, Devin Dawson DYNAMITE BTS HAWAI [Remix] Maluma & The Weeknd DON'T STOP Megan Thee Stallion feat. Young Thug MR. RIGHT NOW 21 Savage & Metro Boomin feat. Drake LAST CHRISTMAS WHAM! GOLDEN HARRY STYLES HAPPY ANYWHERE BLAKE SHELTON feat. GWEN STEFANI HOLIDAY LIL NAS X 34+35 Ariana Grande PRISONER Miley Cyrus feat. -

Hip Hop Matters

HIP HOP MATTERS HIP HOP MATTERS Politics, Pop Culture, and the Struggle for the Soul of a Movement S. Craig Watkins Beacon Press, Boston Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2005 by S. Craig Watkins All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Text design by Patricia Duque Campos Composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Watkins, S. Craig (Samuel Craig) Hip hop matters : politics, pop culture, and the struggle for the soul of a movement / S. Craig Watkins. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8070-0986-5 (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. 2. Hip-hop. I. Title. ML3531.W38 2005 782.421649—dc22 2004024187 FOR ANGELA HALL WATKINS, MY WIFE AND BEST FRIEND CONTENTS PROLOGUE Hip Hop Matters 1 INTRODUCTION Back in the Day 9 PART ONE Pop Culture and the Struggle for Hip Hop CHAPTER ONE Remixing American Pop 33 CHAPTER TWO A Great Year in Hip Hop 55 CHAPTER THREE Fear of a White Planet 85 CHAPTER FOUR The Digital Underground 111 PART TWO Politics and the Struggle for Hip Hop CHAPTER FIVE Move the Crowd 143 CHAPTER SIX Young Voices in the Hood 163 CHAPTER SEVEN “Our Future...Right Here, Right Now!” 187 CHAPTER EIGHT “We Love Hip Hop, But Does Hip Hop Love Us?” 207 CHAPTER NINE Artificial Intelligence? 229 EPILOGUE Bigger Than Hip Hop 249 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 257 NOTES 261 BIBLIOGRAPHY 279 INDEX 283 PROLOGUE Hip Hop Matters Stakes is high. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

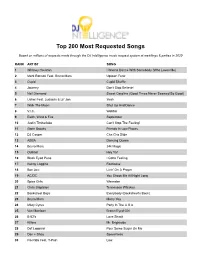

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

2020 Song Index

SEP 26 2020 SONG INDEX 10K (HGA Native Songs, ASCAP/All Essential -B- BLUEBERRY FAYGO (Lil Mosey Publishing CIRCLES (EMI April Music, Inc., ASCAP/Posty DON DON (Los Cangris Publishing, ASCAP/ FREAK (MAU Publishing, Inc., BMI/Prescription Music, ASCAP/Wes The Writer Music, BMI/We Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ Publishing, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publihsing, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt Music Songs, ASCAP/Yeti Yeti Yeti Music, ASCAP/ Are The Good Music Publishing, ASCAP/Atlas BACK HOME (April’s Boy Muzik, BMI/Warner- Callan Wong Publishing Designee, BMI/Franmar WMMW Publishing, ASCAP/Universal Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) LT 10 Cameron Bartolini Music, ASCAP/EPA Publish- Tamerlane Publishing Corp., BMI/Artist Publish- Mountain Songs, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, Music, BMI/Unidisc Music Inc., BMI/Sony/ATV Corp., ASCAP/Nyankingmmusic Inc., ASCAP/ DON’T CHASE THE DEAD (Empire Of Daark- ing, BMI/PW Ballads, BMI/Songs Of Universal, BMI/worshiptogether.com songs, ASCAP/six- ing Group West, ASCAP/My Lord Prophet Music, Songs LLC, BMI/ECAF Music, BMI/Epic/Solar, Quiet As Kept Music Inc., PRS), HL, H100 16 Inc., BMI/Chrysalis Standards, BMI/BMG Plati- ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/Summer ness, BMI/Songs Of Golgotha, BMI/Figs D. steps Music, ASCAP/ThankyouMusic Ltd, PRS/ BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp., BMI/ CITY OF ANGELS (24KGOLDN PUBLISHING, Music, BMI/Concord Publishing, BMI), HL, num Songs US, BMI/Universal Music - Careers, Capitol CMG Genesis, ASCAP), HL, CST 49 Walker Publishing Designee, ASCAP/LVRN Boobie And -

Disc Jockey News Top 100 US Singles December 2, 2020 Page 1

Disc Jockey News Top 100 US Singles December 2, 2020 Page 1 TW LW Title Artist Peak Weeks TW LW Title Artist Peak Weeks 1 new Life Goes On Highest Debut BTS 1 1 26 17 Rockstar Dababy and Roddy Ricch 1 32 2 1 Mood 24Kgoldn and Iann Dior 1 16 27 19 Be Like That Kane Brown featuring Swae Lee and Khalid 19 20 3 14 Dynamite BTS 1 14 28 18 Before You Go Lewis Capaldi 9 43 4 3 Positions Ariana Grande 1 5 29 24 Bang! AJR 24 21 5 4 I Hope Gabby Barrett 3 48 30 27 34+35 Ariana Grande 8 4 6 6 Holy Justin Bieber and Chance The Rapper 3 10 31 re-entry Jingle Bell Rock Best Comeback Bobby Helms 3 16 7 5 Laugh Now Cry Later Drake and Lil Durk 2 15 32 26 Lonely Justin Bieber and Benny Blanco 14 6 8 new Monster Shawn Mendes and Justin Bieber 8 1 33 23 Ily Surf Mesa and Emilee 23 27 9 7 Blinding Lights Longest on Chart The Weeknd 1 52 34 28 Said Sum Moneybagg Yo 17 21 10 8 Lemonade Internet Money featuring Gunna and Toliver 6 15 35 22 Hawái Maluma 12 14 11 2 Therefore I Am Billie Eilish 2 3 36 21 Watermelon Sugar Harry Styles 1 36 12 new Body Megan Thee Stallion 12 1 37 re-entry It’s The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year Andy Williams 7 16 13 new Blue & Grey BTS 13 1 38 34 One Beer Hardy featuring Lauren Alaina and Devin Dawson 33 25 14 29 All I Want For Christmas Is You Mariah Carey 1 38 39 30 Whats Poppin Jack Harlow 2 42 15 9 Dakiti Bad Bunny and Jhay Cortez 8 4 40 33 One Of Them Girls Lee Brice 17 26 16 10 For The Night Pop Smoke 6 21 41 32 What You Know Bout Love Pop Smoke 25 12 17 12 Go Crazy Chris Brown and Young Thug 9 29 42 re-entry Last Christmas -

Savage Remix Lyrics – Megan Thee Stallion

Savage Remix Lyrics – Megan Thee Stallion : Good News | No.1 Lyrics Bros Savage Remix Lyrics – Megan Thee Stallion : On the remix to Megan Thee Stallion’s hot single “Savage,” Meg teams up with fellow Houston native Beyoncé for the first time. The two first met at a New Year’s Eve party in December 2019. Song : Savage Remix Artist : Megan Thee Stallion Featuring : Beyoncé Produced by : J. White Did It Album : Good News Savage Remix Lyrics Megan Thee Stallion [Intro: Beyoncé] Savage Remix Lyrics Queen B, want no smoke with me (Okay) Been turnt, this motherfucker up eight hundred degree (Yeah) My whole team eat, chef’s kiss, she’s a treat (Mwah) Ooh, she so bougie, bougie, bon appétit [Verse 1: Megan Thee Stallion, Beyoncé & Both] I’m a savage (Yeah), attitude nasty (Yeah, ah) Talk big shit, but my bank account match it (Ooh) Hood, but I’m classy, rich, but I’m ratchet (Oh, ah) Haters kept my name in they mouth, now they gaggin’ (Ah, ah) Bougie, he say, “The way that thang move, it’s a movie” (Ooh-oh) I told that boy, “We gotta keep it low, leave me the room key” (Ooh-oh) I done bled the block and now it’s hot, bitch, I’m Tunechi (Ooh-oh) A mood and I’m moody, ah Savage Remix Lyrics [Chorus: Megan Thee Stallion & Beyoncé] I’m a savage, yeah (Okay) Classy, bougie, ratchet, yeah (Okay) Sassy, moody, nasty, yeah (Hey, hey, nasty) Acting stupid, what’s happening? (Woah, woah, woah, what’s happening?) Bitch, what’s happening? (Woah, woah, okay) Bitch, I’m a savage, yeah (Okay) Classy, bougie, ratchet, yeah (Ratchet) Sassy, moody, nasty, huh (Nasty) -

WHAT's GOOD in DA HOOD? HOODOLOGY in ORGANIZATIONS by QUEEN JAKS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For

WHAT’S GOOD IN DA HOOD? HOODOLOGY IN ORGANIZATIONS by QUEEN JAKS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Organizational Behavior CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2021 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Queen Jaks candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. Committee Chair Diana Bilimoria Committee Member Corinne Coen Committee Member Melvin Smith Committee Member Robert Bonner Date of Defense November 24th, 2020 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein 2 3 Copyright ã 2020 Queen Jaks ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 3 4 DEDICATION This is for the streets that raised me, that made me. This is for all those in the gutter struggling in style. This is for all the souls who feel no existence in this society. You are the universe. They are nothing without you. To all those in the hood. This is our time. Rise up. 4 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF FIGURES....................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................ 12 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

In the Cinematic Hood:“Who You Callin'a Hoe?”

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election (Re)visiting Black Women and Girls in the Cinematic Hood: “Who you callin’ a hoe?” Emma Horrex Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12080 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12080 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Emma Horrex, « (Re)visiting Black Women and Girls in the Cinematic Hood: “Who you callin’ a hoe?” », European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 11, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12080 ; DOI : 10.4000/ ejas.12080 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Creative Commons License (Re)visiting Black Women and Girls in the Cinematic Hood: “Who you callin’ a ... 1 (Re)visiting Black Women and Girls in the Cinematic Hood: “Who you callin’ a hoe?” Emma Horrex 1. Introducing the Black Women and Girls in the Hood via Boyz 1 Amidst an ongoing debate regarding the lack of racial diversity in last year’s Oscar nominations (2016), Boyz N the Hood (Boyz, 1991) was honoured by the African American Film Critics Association during a “Celebration of Hip Hop Cinema” in February 2016, twenty-five years since capturing the public imagination and academic attention. Directed by John Singleton, the film emerged during and reflected an important moment of the post-Reagan political and cinematic landscape. President Bush’s inaugural address in 1989 claimed that America was “in a peaceful, prosperous time” but despite increasing the minimum wage, the economic recession in July 1990 undercut this notion as widespread poverty penetrated the ghettos.i Economic pressures in the late 1980s and early 1990s (largely due to Reagan’s exacerbation of unemployment rates amongst minority groups and dismantling of the welfare system) contributed to the proliferation of street gangs and the underground drugs economy in local urban environments.