Hip Hop Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Research.Pdf (2.230Mb)

THE ATTAINMENT OF SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH ADOELCSENT GIRLS LIVING AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY IN A COMMUNITY-BASED PEDAGOGICAL SPACE KNOWN AS AUNTIE’S PLACE _______________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Learning, Teaching and Curriculum College of Education at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by ADRIAN CLIFTON Dr. Lenny Sanchez, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2016 © Copyright by Adrian Clifton 2016 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE ATTAINMENT OF SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH ADOELCSENT GIRLS LIVING AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY IN A COMMUNITY-BASED PEDAGOGICAL SPACE KNOWN AS AUNTIE’S PLACE presented by Adrian Clifton, a candidate for the degree of [doctor of philosophy, doctor of education of _____________________________________________________________________, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Lenny Sanchez Professor Ty-Ron Douglas Professor Treva Lindsey Professor Jill Ostrow SOCIAL CAPITAL ATTAINMENT WITH ADOLESCENTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND POVERTY Dedication I would like to dedicate this body of work to my mother, Verna Laboy, whose constant belief in me facilitated this great accomplishment. Mom, thanks for believing that I could have the world. It is important to highlight my husband. Collectively we have achieved this great accomplishment. Thank you Herman for being my rock. To my brother and sisters: Nicole McGruder, LaShai Hamilton, Shawn Harris, who have been pillars of support during this process. To my son, Herman Clifton IV, and daughters, Amari, Serenity and Adrian, whose patience and unwavering support of their mother has been stoic. -

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

Lyrics and the Law : the Constitution of Law in Music

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2006 Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music. Aaron R. S., Lorenz University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Lorenz, Aaron R. S.,, "Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music." (2006). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2399. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2399 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2006 Department of Political Science © Copyright by Aaron R.S. Lorenz 2006 All Rights Reserved LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Approved as to style and content by: Sheldon Goldman, Member DEDICATION To Martin and Malcolm, Bob and Peter. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been a culmination of many years of guidance and assistance by friends, family, and colleagues. I owe great thanks to many academics in both the Political Science and Legal Studies fields. Graduate students in Political Science have helped me develop a deeper understanding of public law and made valuable comments on various parts of this work. -

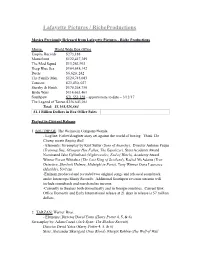

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

50 Cent to Join Eminem Shade 45 Channel Shade 45 Channel

50 Cent To Join Eminem Shade 45 Channel Shade 45 Channel "G Unit Radio" to Air All Day Saturdays With a Lineup of DJs and Shows NEW YORK – February 24, 2005 – SIRIUS Satellite Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) announced today that multi-platinum artist 50 Cent will create and host exclusive programming on Shade 45, the new uncensored hip-hop radio channel co-produced by SIRIUS and Eminem. 50 Cent will oversee G Unit Radio, which will take over Shade 45 all day on Saturdays with an innovative mix of shows and DJs produced by his own DJ, Whoo Kid. “I’m bringing my A-game to SIRIUS,”said 50 Cent. “G Unit Radio is gonna blow up on Shade 45.” “Eminem and 50 Cent are two of the biggest names in hip-hop today" said SIRIUS President of Sports and Entertainment Scott Greenstein. “On Shade 45, 50 Cent will bring G Unit’s world to SIRIUS listeners.” SIRIUS launched Shade 45, the uncensored, commercial-free hip-hop music channel created by Eminem, Shady Records, Interscope Records and SIRIUS in October 2004. The channel also features other high profile figures in the world of hip-hop, including Eminem’s own DJ Green Lantern and Radio/Mixshow DJ of the Year Clinton Sparks. The channel also regularly features celebrity guests. 50 Cent, one of the most notorious figures in rap music, is also one of its most successful. His 2003 debut album, Get Rich or Die Tryin’, has sold more than 11 million copies. He has launched a successful G Unit clothing and footwear line, and can also be seen in an upcoming Jim Sheridan film, which is reported to be a semi-autobiographical film based on his ascension from drug dealer to superstar. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:446 洋楽最新ヒット 放送日:2020/12/14~2020/12/20 「番組案内 (4時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/8:00~/12:00~/16:00~/20:00~/24:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■洋楽最新ヒット HOLY Justin Bieber feat. Chance The Rapper I Hope GABBY BARRETT LIFE GOES ON BTS POSITIONS Ariana Grande LEVITATING DUA LIPA feat. DABABY GO CRAZY CHRIS BROWN & YOUNG THUG More Than My Hometown Morgan Wallen Dakiti Bad Bunny & Jhay Cortez Mood 24kGoldn feat. Iann Dior WAP [Lyrics!] CARDI B feat. Megan Thee Stallion MONSTER SHAWN MENDES & JUSTIN BIEBER THEREFORE I AM BILLIE EILISH Lemonade Internet Money feat. Gunna, Don Toliver, NAV KINGS & QUEENS Ava Max BLINDING LIGHTS The Weeknd SAVAGE LOVE (Laxed-Siren Beat) JAWSH 685×Jason Derulo BEFORE YOU GO Lewis Capaldi FOR THE NIGHT Pop Smoke feat. Lil Baby & Dababy BE LIKE THAT Kane Brown feat. Swae Lee & Khalid BANG! AJR All I Want For Christmas Is You (恋人たちのクリスマス) MARIAH CAREY LONELY Justin Bieber & Benny Blanco WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES LAUGH NOW CRY LATER DRAKE feat. LIL DURK Love You Like I Used To RUSSELL DICKERSON Starting Over Chris Stapleton 7 SUMMERS Morgan Wallen DIAMONDS SAM SMITH FOREVER AFTER ALL LUKE COMBS BETTER TOGETHER LUKE COMBS WHATS POPPIN Jack Harlow ROCKSTAR DABABY feat. RODDY RICCH SAID SUM Moneybagg Yo ONE BEER HARDY feat. Lauren Alaina, Devin Dawson DYNAMITE BTS HAWAI [Remix] Maluma & The Weeknd DON'T STOP Megan Thee Stallion feat. Young Thug MR. RIGHT NOW 21 Savage & Metro Boomin feat. Drake LAST CHRISTMAS WHAM! GOLDEN HARRY STYLES HAPPY ANYWHERE BLAKE SHELTON feat. GWEN STEFANI HOLIDAY LIL NAS X 34+35 Ariana Grande PRISONER Miley Cyrus feat. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board James Abbington, DMA Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship Candler School of Theology, Emory University William C. Banfield, DMA Professor of Africana Studies, Music, and Society Berklee College of Music Johann Buis, DA Associate Professor of Music History Wheaton College Eileen M. Hayes, PhD Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology College of Music, University of North Texas Cheryl L. Keyes, PhD Professor of Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles Portia K. Maultsby, PhD Professor of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Director of the Archives of African American Music and Culture Indiana University, Bloomington Ingrid Monson, PhD Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music Harvard University Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., PhD Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music University of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia of African American Music Volume 1: A–G Emmett G. Price III, Executive Editor Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Associate Editors Copyright 2011 by Emmett G. Price III, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of African American music / Emmett G. Price III, executive editor ; Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., associate editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1 (set hard copy : alk.