Kelsey A. Fuller, University of Colorado, Boulder, “ 'Reindeer Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

In "Frozen" Musical, Kingdom of Arendelle Re- Created for Broadway by Peter Marks, Washington Post, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 03.01.18 Word Count 652 Level 870L

In "Frozen" musical, kingdom of Arendelle re- created for Broadway By Peter Marks, Washington Post, adapted by Newsela staff on 03.01.18 Word Count 652 Level 870L Patti Murin as Anna and John Riddle as Hans in "Frozen." Photo by: Deen van Meer Michael Grandage has won major awards for his theater productions, but none of his experience prepared him for his latest project. Now, he has to deal with a character with a carrot nose who's likely to melt. That's because his latest project is Disney's "Frozen." Performances of the play began on February 22. Grandage's stage version is based on the 2013 animated Disney film that made $1.3 billion around the world. Grandage and his team have been hard at work for more than a year. They hope their musical can live up to the movie. Disney Told Grandage To Be True To The Movie Grandage is new to Disney and had never directed an original musical until now. He has the difficult job of meeting the high expectations set by the "Frozen" movie. He must create new magic using whimsical characters like Olaf the Snowman and Sven the Reindeer from Elsa and Anna's kingdom of Arendelle. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. No pressure! Disney challenged Grandage to be true to the original movie while still coming up with novel surprises. Which brings us back to Olaf. In the movie, he's drawn by Disney's animators as three balls of heartwarming snow. "That's your first question when you do a stage version," Grandage says. -

Here I Didn't Dream About All the Potential Stories and Scenarios That Could Unfold in a Possible Sequel

Seek the Truth: Unraveling Frozen II Written by Yumeka June 29, 2020 (1st edition) November 11, 2020 (2nd edition) animeyume.com/yume_dimension twitter.com/Yumeka36 yumeka36.tumblr.com Cover art by Charles Tan behance.net/charlestan twitter.com/charlestan Frozen II screenshots used courtesy of Animation Screencaps animationscreencaps.com/4k-frozen-ii-2019/ Frozen, Frozen II, and all related characters and media are owned by Disney. This is an unofficial, commercial-free digital book that came about from a fan's passion Also, special thanks to Mari Mancusi, author of Dangerous Secrets: the Story of Iduna and Agnarr, for taking the time to answer my questions about the lore and events presented in the book. The help was greatly appreciated! 1 Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 – Arendelle and the Northuldra .................................................... 5 Chapter 2 – A Voice from the Unknown .................................................... 11 Chapter 3– The Spirits ................................................................................ 19 Chapter 4– Those Shut In and the One Shut Out ....................................... 28 Chapter 5– Magic's Core ............................................................................. 33 Chapter 6– A Bridge Has Two Sides ........................................................... 37 Afterword ................................................................................................... -

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

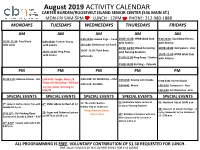

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

Media and Games Invest Level Up

Release date: 09 October 2020 Market data as of: 08 October 2020 Media and Games Invest Germany | Holding companies MCap: EUR95.9m This report is intended for [email protected]. Unauthorized distribution prohibited. Buy (Not Rated) Level Up Target Price: EUR2.30 (none) Current Price: EUR1.37 What’s it all about? Up/downside: 67.9% We initiate coverage with a Buy on Media and Games Invest plc (MGI), a buy-and- Change in TP: none build market consolidator in online video gaming and digital advertising. Digital Change in Adj. EPS: none 19E/NM+ 20E entertainment has emerged as a COVID-19 safe haven. We see significant upside to MGI’s current share price assuming a successful continuation of management’s M&A strategy, and with consolidation benefits in its media segment yielding margin expansion. Gaming has reached a new era; we invite investors to reassess its attractiveness with MGI shares, which offer a profitable gaming portfolio with a Sven Sauer proven M&A strategy and beneficial market dynamics, complemented by an Equity Research Analyst attractive digital advertising portfolio and significant inter-segment synergy +49 69 7 56 96 131 potential. [email protected] Holding companies research team Biographies at the end of this document Kepler Cheuvreux and the issuer have agreed that Kepler Cheuvreux will produce and disseminate investment research on the said issuer as a service to the issuer. IMPORTANT. Please refer to keplercheuvreux.com\disclaimer for keplercheuvreux.com This research is the product of Kepler Cheuvreux, which is authorized and “Important disclosures” and analyst certification(s). regulated by the Autorité des Marchés Financiers in France. -

Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Essay Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess Madeline Streiff 1 and Lauren Dundes 2,* 1 Hastings College of the Law, University of California, 200 McAllister St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-410-857-2534 Academic Editors: Michele Adams and Martin J. Bull Received: 10 September 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Disney’s animated feature Frozen (2013) received acclaim for presenting a powerful heroine, Elsa, who is independent of men. Elsa’s avoidance of male suitors, however, could be a result of her protective father’s admonition not to “let them in” in order for her to be a “good girl.” In addition, Elsa’s power threatens emasculation of any potential suitor suggesting that power and romance are mutually exclusive. While some might consider a princess’s focus on power to be refreshing, it is significant that the audience does not see a woman attaining a balance between exercising authority and a relationship. Instead, power is a substitute for romance. Furthermore, despite Elsa’s seemingly triumphant liberation celebrated in Let It Go, selfless love rather than independence is the key to others’ approval of her as queen. Regardless of the need for novel female characters, Elsa is just a variation on the archetypal power-hungry female villain whose lust for power replaces lust for any person, and who threatens the patriarchal status quo. The only twist is that she finds redemption through gender-stereotypical compassion. -

Digital Media: Rise of On-Demand Content 2 Contents

Digital Media: Rise of On-demand Content www.deloitte.com/in 2 Contents Foreword 04 Global Trends: Transition to On-Demand Content 05 Digital Media Landscape in India 08 On-demand Ecosystem in India 13 Prevalent On-Demand Content Monetization Models 15 On-Demand Content: Music Streaming 20 On-Demand Content: Video Streaming 28 Conclusion 34 Acknowledgements 35 References 36 3 Foreword Welcome to the Deloitte’s point of view about the rise key industry trends and developments in key sub-sectors. of On-demand Content consumption through digital In some cases, we seek to identify the drivers behind platforms in India. major inflection points and milestones while in others Deloitte’s aim with this point of view is to catalyze our intent is to explain fundamental challenges and discussions around significant developments that may roadblocks that might need due consideration. We also require companies or governments to respond. Deloitte aim to cover the different monetization methods that provides a view on what may happen, what could likely the players are experimenting with in the evolving Indian occur as a consequence, and the likely implications for digital content market in order to come up with the various types of ecosystem players. most optimal operating model. This publication is inspired by the huge opportunity Arguably, the bigger challenge in identification of the Hemant Joshi presented by on-demand content, especially digital future milestones about this evolving industry and audio and video in India. Our objective with this report ecosystem is not about forecasting what technologies is to analyze the key market trends in past, and expected or services will emerge or be enhanced, but in how they developments in the near to long-term future which will be adopted.