Experimenter Effects and the Remote Detection of Staring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 November 2016 Programme

Programme 8 November 2016 BAFTA, London Huxley Summit Agenda 2016 3 Contents Agenda Agenda page 3 08:30 Registration Chapters page 4 09:00 Chapter 1: State of the nation Trust in the 21st Century page 6 Why trust matters page 8 10:30 Coffee and networking Speakers page 12 11:10 Chapter 2: Who do we trust? Partners page 18 12:20 Lunch and networking Attendees page 19 Round table on corporate sponsored research Round table on reasons for failure 13:50 Chapter 3: Who will we trust? 15:20 Coffee and networking 16:00 Chapter 4: Who should we trust? 17:45 Closing remarks 18:00 Drinks reception A film crew and photographer will be present at the Huxley Summit. If you do not wish to be filmed or photographed, please speak to a member of the team at British Science Association. We encourage attendees to use Twitter during the Summit, and we recommend you use the hashtag #HuxleySummit to follow the conversations. 4 Huxley Summit 2016 Chapters 5 Chapter 1: Chapter 2: Chapter 3: Chapter 4: State of the nation Who do we trust? Who will we trust? Who should we trust? The global events of 2016 have caused Many sections of business, politics and The public need to be engaged and Trust and good reputations are hard many people to question who they trust. public life have had a crisis of public informed on innovations in science won but easily lost. What drives How is this affecting the role of experts trust in recent years, but who do we trust and technology that are set to have consumers’ decision making and how and institutions? How can leaders from with science? And what can we learn a big impact on their lives and the can we drive trust in our businesses across politics, business, science and from the handling of different areas of world around them. -

Psychology of Paranormal Belief.Indd 7 2/6/09 15:44:55 Viii the Psychology of Paranormal Belief

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Foreword to Citation for published version: Watt, C & Wiseman, R 2009, Foreword to. in HJ Irwin (ed.), The Psychology of Paranormal Belief: A Reseracher's Handbook. University of Hertfordshire Press, pp. 7. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: The Psychology of Paranormal Belief: A Reseracher's Handbook Publisher Rights Statement: © Watt, C., & Wiseman, R. (2009). Foreword to. In H. J. Irwin (Ed.), The Psychology of Paranormal Belief: A Reseracher's Handbook. (pp. 7). University of Hertfordshire Press. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 Foreword Dr Caroline Watt, Koestler Parapsychology Unit, University of Edinburgh Professor Richard Wiseman, Department of Psychology, University of Hertfordshire he term ‘paranormal belief’ tends to be carelessly used as if it were referring to a Tmonolithic belief in phenomena for which science has no explanation. -

Richard Wiseman at Hampton Court

Hampton Court Investigation 1 Published in Journal of Parapsychology, 66(4), 387-408. An investigation into the alleged haunting of Hampton Court Palace: Psychological variables and magnetic fields Dr Richard Wiseman University of Hertfordshire Dr Caroline Watt University of Edinburgh Emma Greening University of Hertfordshire Dr Paul Stevens University of Edinburgh Ciaran O'Keeffe University of Hertfordshire Abstract Hampton Court Palace is reputed to be one of the most haunted places in England, with both staff and visitors reporting unusual phenomena in many areas of the building. Our investigation aimed to discover the extent to which these reports were related to three variables often proposed to account for alleged hauntings, namely, belief in ghosts, suggestion and magnetic fields. Over 600 members of the public took part in the experiment. Participants completed Likert-type questionnaires measuring their belief in ghosts, the unusual phenomena they had experienced in the past and whether they thought these phenomena were due to ghosts. Participants who believed in ghosts reported significantly more unusual phenomena than disbelievers, and were significantly more likely to attribute the phenomena to ghosts. Participants then walked around an allegedly haunted area of the Palace and provided reports about unusual phenomena they experienced. Believers reported significantly more anomalous experiences than disbelievers, and were significantly more likely to indicate that these had been due to a ghost. Prior to visiting the locations, half of the participants were told that the area was associated with a recent increase in unusual phenomena, whilst the others were told the opposite. In line with previous work on the psychology of paranormal belief, the number of unusual experiences reported by participants showed a significant interaction between belief in ghosts and these suggestions. -

I Can Read Your Mind Youtube

I can read your mind youtube I'm about to read your mind with 3 different mind tricks. Zach King will teach you how to trick your friends. I can read your mind - Alan Parson's Project (with onscreen lyrics) . take no offense, but this YouTube audio. Music video by Avant performing Read Your Mind. dafuq , good thing YouTube is here so we can relive. This great mind reading trick uses music from: "Beachfront celebration" Kevin MacLeod ( This video asks you to use your imagination and ultimately tells you exactly what you are thinking of. An. This video uses an amazing math trick to give off that mind- reading effect - be amazed! Share with your. Magician Collins Key Tries some CRAZY MIND READING! Thumbs Up if it WORKED!! WIN A iPhone 6S. im your king be my queen . when you walking and this song comes on and you start biting your lip. me The sun in your eyes Made some of the lies worth believing I am the eye in the sky Looking at you I can. Song identification of video "Songs in "I can" Youtube id myT5pa0jxZ0 by Description: Watch this video of how I can read your mind through YouTube, if I can't, then you've mis-read. I can read your mind through YouTube - YouTube. di Thomas8april. Rebloging This!!!! My gma had to battle cancer. She won, but it was tough to see her go. I'm your king be my queen. And what ever you wanna do tonight. My truck is parked out front so lets ride [Hook] I can read your mind, babe. -

A Night out with the Nerds Sandra Knapp, James Mallet*

Open access, freely available online Book Review/Science in the Media A Night Out with the Nerds Sandra Knapp, James Mallet* dd performance to science, the European Organization for Nuclear away.) Then Du Sol’s performance— and the equation results in Research (CERN) (see http:⁄⁄www. accompanied by theramin music and ATheatre of Science. Part scientifi c simonsingh.net). Wiseman is a overlaid with recordings of her talking lecture, part magic show, and part magician (a failed magician, he says, about how she felt while performing, in music and dance, Theatre of Science is as he deliberately drops a card he has particular how she hoped that people an innovative collaboration between palmed). Instead, he is now the world’s didn’t perceive her as a freak—opened Simon Singh and Richard Wiseman. only Professor of Public Understanding up a new dimension. The contrast The cosy atmosphere of the Soho of Psychology, at the University of between her matter-of-fact speech Theatre, stuffed with a lively crowd, Hertfordshire (see http:⁄⁄www. and the tension in the audience was which appeared swelled by a smattering richardwiseman.net). Wiseman’s forte unnerving. of family and friends, makes the is optical illusion, the magician’s stock- Although the show doesn’t end show a personal interchange between in-trade, but most impressive is his with a thunderous bang, it does have performers and audience. Several exploration of quirks of our perception real lightning—every bit as good. This in the audience must have been of ordinary things. “Psychologists today fi nal experiment (or do we mean scientists, judging by appearances: one earnestly debate if anything we see is skit?) requires two six-foot-high, out-of- enthusiastic member of the audience real at all”, he says. -

Controversial Study Promoting Psychic Ability Debunked 14 March 2012

Controversial study promoting psychic ability debunked 14 March 2012 In response to a 2011 study suggesting the the original list. Results showed that participants existence of precognition, or the ability to predict were better at remembering the words they were future events using psychic powers, a new group about to be shown, indicating they had reached of researchers report that attempts to replicate the forward in time to 'practice' those words in the previous results were unsuccessful. These results future. therefore do not support the previous claims for the existence of psychic ability. The full report is Within parapsychology, there is a tendency to published Mar. 14 in the open access journal PLoS accept any positive replications but to dismiss ONE. failures to replicate if the procedures followed have not been exactly duplicated. Research failing to find evidence for the existence of psychic ability has been published, following a "We went to great pains to ensure we followed the year of industry debate. same procedures as Bem," said Stuart Ritchie. "Using Bem's own computer programme and stats The report is a response by a group of methods, we replicated his experiment three times, independent researchers to the 2011 study from at each of our respective campuses, with the same social psychologist Daryl Bem, purporting the number of participants as the original study." existence of precognition - an ability to perceive future events. "By having our paper published, we hope academic journals and popular media alike will offer the same Professor Chris French (Goldsmiths, University of weight to negative results as given to eye-catching London), Stuart Ritchie (University of Edinburgh) positive results," said Professor Richard Wiseman. -

CBIS Annual Report

2016 CBIS Annual Report The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies at Imperial College London April 2017 © Imperial College London 2016 1 Centre for Blast Injury Studies Annual Report The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies at Imperial College London www.imperial.ac.uk/blast-injury London, April 2017 Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine © Imperial College London 2017 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Director’s Foreword ............................................................................................................................... 5 Invited Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Staffing & Facilities ................................................................................................................................. 2 Governance ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Due Diligence ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Being a Researcher in CBIS .................................................................................................................... -

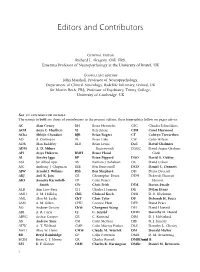

Editors and Contributors

Date : 9:8:2004 File Name: Prelims.3d 10/20 Editors and Contributors General editor Richard L. Gregory, CBE, FRS, Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, UK Consultant editors John Marshall, Professor of Neuropsychology, Department of Clinical Neurology, Radcliffe In®rmary, Oxford, UK Sir Martin Roth, FRS, Professor of Psychiatry, Trinity College, University of Cambridge, UK Key to contributor initials The names in bold are those of contributors to the present edition; their biographies follow on pages xiii±xv. AC Alan Cowey BH Beate Hermelin CSC Claudia SchmoÈlders ACH Anya C. Hurlbert BJ Bela Julesz CSH Carol Haywood ACha Abhijit Chauduri BJR Brian Rogers CT Colwyn Trevarthen AD A. Dickinson BL Brian Lake CW Colin Wilson ADB Alan Baddeley BLB Brian Lewis DaC David Chalmers ADM A. D. Milner Butterworth DAGC David Angus Graham AH Atiya Hakeem BMH Bruce Hood Cook AI Ainsley Iggo BP Brian Pippard DAO David A. Oakley AJA Sir Alfred Ayer BS Barbara J. Sahakian DC David Cohen AJC Anthony J. Chapman BSE Ben Semeonoff DCD Daniel C. Dennett AJW Arnold J. Wilkins BSh Ben Shephard DD Diana Deutsch AKJ Anil K. Jain CE Christopher Evans DDH Deborah Duncan AKS Annette Karmiloff- CF Colin Fraser Honore Smith CFr Chris Frith DDS Doron Swade ALB Ann Low-Beer CH Charles Hannam DE Dylan Evans AMH A. M. Halliday ChK Christof Koch DEB D. E. Blackman AML Alan M. Leslie ChT Chris Tyler DF Deborah H. Fouts AMS A. M. Sillito CHU Corinne Hutt DFP David Pears AO Andrew Ortony ChW Chongwei Wang DH David Howard ARL A. -

Achieving the Impossible: a Review of Magic-Based Interventions and Their Effects on Wellbeing

Achieving the impossible: a review of magic-based interventions and their effects on wellbeing Richard Wiseman1 and Caroline Watt2 1 Psychology, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom 2 Psychology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Research has demonstrated that involvement with mainstream performing arts, such as music and dance, can boost wellbeing. This article extends this work by reviewing little-known research on whether learning magic tricks can have an equally beneficial effect. We first present an historic overview of several magic-based interventions created by magicians, psychologists and occupational therapists. We then identify the potential benefits of such interventions, and review studies that have attempted to systematically assess these interventions. The studies have mostly revealed beneficial outcomes, but much of the work is of poor methodological quality (involving small numbers of participants and no control group), and has tended to focus on clinical populations. Finally, we present guidelines for future research in the area, emphasizing the need for more systematic and better-controlled studies. Subjects Psychiatry and Psychology, Public Health Keywords Psychology, Occupational therapy, Magic tricks, Health, Intervention, Performing arts INTRODUCTION Submitted 15 October 2018 Research has shown that involvement with the performing arts can help boost psychological Accepted 7 November 2018 and physical wellbeing (for reviews see Fraser, Bungay & Munn-Giddings, 2014; Noice, Noice Published 6 December 2018 & Kramer, 2014; Stickley et al., 2017). This work has employed a variety of research designs Corresponding author (including randomised controlled trials, case studies, and observational designs) and Richard Wiseman, [email protected], tackled a wide variety of topics (including mental health issues, dementia and Parkinson's [email protected] disease, chronic illnesses, head injuries, substance abuse, and physical and developmental Academic editor disabilities). -

CSI's Balles Prize Goes to Richard Wiseman For

Sep Oct pages cut_SI new design masters 8/1/12 9:54 AM Page 5 [ NEWS AND COMMENT CSI’s Balles Prize Goes to Richard Wiseman for Paranormality BARRY KARR The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) will award its 2011 Robert P. Balles Annual Prize in Critical Think - ing to psychologist Richard Wiseman for his book Paranormality: Why We See What Isn’t There. Wiseman holds Britain’s only Chair in the Public Understanding of Psy chology, at the University of Hertford shire (UK). He has written several best-selling books, including The Luck Factor, Quirkology, 59 Seconds, and Paranormal ity. More than two million people have taken part in his mass participation experiments, and his YouTube channel has received more than thirty million views. He is one of the most frequently quoted psychologists in the British media and was recently listed data or to explain apparently preternat- as one of the Inde pendent on Sunday’s top ural phenomena. 100 people who make Britain a better This is the seventh year the Robert place to live. He is also a Committee for P. Balles prize has been presented. Pre- KEPTI Skep tical Inquiry fellow and a S - vious winners of this award are: CAL INQUIRER consulting editor. Paranormality is not like a good num- 2010: Steven Novella for his tre - mendous body of work, including the ber of skeptical books looking at paranor- Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe, Science- mal claims. Wiseman is not simply inter- Based Medicine, Neurologica, SKEPTI- ested in looking at a claim, gathering the CAL INQUIRER column “The Science evidence, and debunking the claim. -

Research Archive

Research Archive Citation for published version: Richard Wiseman, and Adrian M. Owen, ‘Turning the Other Lobe: Directional Biases in Brain Diagrams’, i-Perception, Vol. 8 (3): June 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2041669517707769 Document Version: This is the Published version. Copyright and Reuse: © 2017 The Author(s). This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License CC-BY 3.0 (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open- access-at-sage). Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] Short and Sweet i-Perception Turning the Other Lobe: May-June 2017, 1–4 ! The Author(s) 2017 DOI: 10.1177/2041669517707769 Directional Biases in journals.sagepub.com/home/ipe Brain Diagrams Richard Wiseman Department of Psychology, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Herts, UK Adrian M. Owen The Brain and Mind Institute, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Abstract Past research shows that in drawn or photographic portraits, people are significantly more likely to be posed facing to their right than their left. We examined whether the same type of bias exists among sagittal images of the human brain. An exhaustive search of Google images using the term ‘brain sagittal view’ yielded 425 images of a left or right facing brain. The direction of each image was coded and revealed that 80% of the brains were right-facing. -

Surgeon "Turned" Physician: the Career and Writings

SURGEON "TURNED" PHYSICIAN: THE CAREER AND WRITINGS OF DANIEL TURNER (1667-1741) PHILIP KEVIN WILSON Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London University of London 1992 ProQuest Number: 10630246 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10630246 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses upon the surgical and medical career and writings of the London practitioner, Daniel Turner (1667-1741). After apprenticeship, Turner entered the Barber-Surgeons* Company in 1691. His pursuit of private dissection exemplifies what he claimed was the "absolute necessity" for surgeons to gain a practical knowledge of anatomy. Turner crusaded to expose surgical "pretenders" and to reform the "vulgar" state of surgery in order to improve the care qualified surgeons could offer and to prevent the public from falling prey to "quacks". He presented apprenticeship in his Art of Surgery as a model for those entering a surgical career, endorsing it with examples from his practice. Turner's career offers a remarkable example of the struggles, successes, and failures of one individual's attempt to move upward in Augustan society.