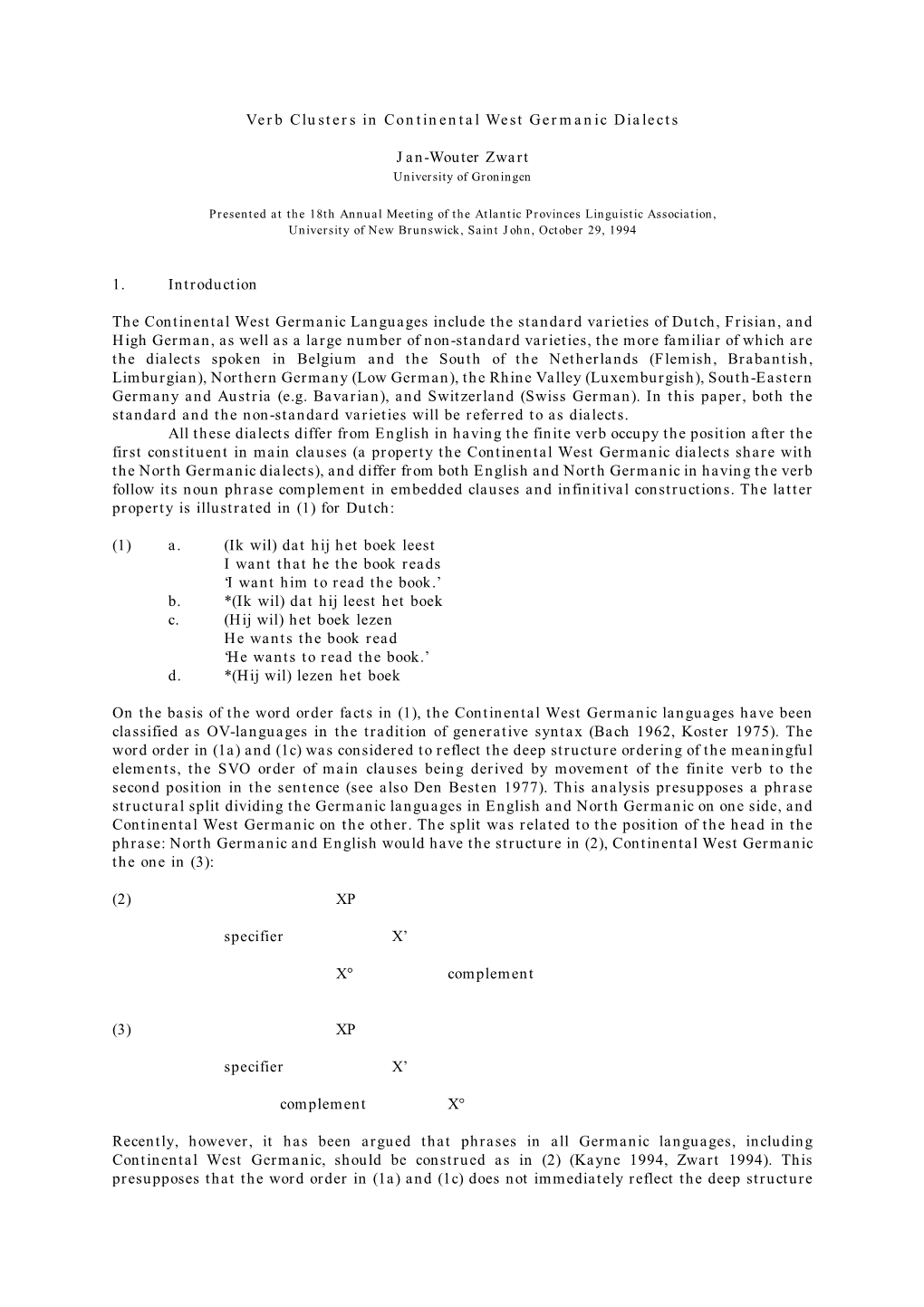

Verb Clusters in Continental West Germanic Dialects Jan-Wouter Zwart 1. Introduction the Continental West Germanic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

New Arguments for Verb Cluster Formation at PF and a Right-Branching VP

New arguments for verb cluster formation at PF and a right-branching VP. Evidence from verb doubling and cluster penetrability* version October 12, 2013; to appear in Linguistic Variation Martin Salzmann, University of Leipzig ([email protected]) Abstract This paper provides new evidence that verb cluster formation in West Germanic takes place post- syntactically. Contrary to some previous accounts, I argue that cluster formation involves linearly adjacent morphosyntactic words and not syntactic sister nodes. The empirical evidence is drawn from Swiss German verb doubling constructions where intriguing asymmetries arise between ascending and descending orders. The approach additionally solves the cluster puzzle with extraposition and topicalization, generates all of the crosslinguistically attested six orders in the verbal complex and correctly predicts which orders are penetrable in which positions. On a more general level, the paper provides arguments for a derivational treatment of verb cluster formation and order variation and adduces important evidence in favor of a right-branching VP. 1 Introduction: Verb clusters in West Germanic In this section I will briefly lay out the central properties of West-Germanic verb clusters. Given the vast literature, I will confine myself to the aspects that will play a role in the ensuing discussion. For a detailed survey both over facts and analyses, the reader is referred to Wurmbrand (2005). West Germanic OV-languages are famous for their verb clusters, i.e. the phenomenon that the verbal elements of a clause all occur together clause-finally (under verb second, where the finite verb moves to C, only the non-finite verbs occur together). -

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Nonnative Acquisition of Verb Second: on the Empirical Underpinnings of Universal L2 Claims

Nonnative acquisition of Verb Second: On the empirical underpinnings of universal L2 claims Ute Bohnacker Lund University Abstract Acquiring Germanic verb second is typically described as difficult for second-language learners. Even speakers of a V2-language (Swedish) learning another V2-language (German) are said not to transfer V2 but to start with a non-V2 grammar, following a universal developmental path of verb placement. The present study contests this claim, documenting early targetlike V2 production for 6 Swedish ab-initio (and 23 intermediate) learners of German, at a time when their interlanguage syntax elsewhere is nontargetlike (head-initial VPs). Learners whose only nonnative language is German never violate V2, indicating transfer of V2-L1 syntax. Informants with previous knowledge of English are less targetlike in their L3-German productions, indicating interference from non-V2 English. V2 per se is thus not universally difficult for nonnative learners. in press in: Marcel den Dikken & Christina Tortora, eds., 2005. The function of function words and functional categories. [Series: Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today] Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins (pp. 41-77). Nonnative acquisition of Verb Second: On the empirical underpinnings of universal L2 claims Ute Bohnacker Lund University 1. Introduction This paper investigates the acquisition of verb placement, especially verb second (V2), by native Swedish adults and teenagers learning German. Several recent publications (e.g. Platzack 1996, 2001; Pienemann 1998; Pienemann & Håkansson 1999; Håkansson, Pienemann & Sayehli 2002) have claimed that learners, irrespective of their first language (L1), take the same developmental route in the acquisition of syntax of a foreign or second language (L2). -

The Origins of Old English Morphology

Englisches Seminar der Universitat¨ Zurich¨ The Origins of Old English Morphology Hausarbeit der Philosophischen Fakultat¨ der Universitat¨ Zurich¨ im Fach Englische Sprachwissenschaft Referentin: Prof. Dr. Gunnel Tottie Stefan Hofler¨ Wiesenbachstrasse 7a CH-9015 St. Gallen +41 71 / 310 16 65 shoefl[email protected] Zurich,¨ 26. September 2002 Contents Symbols and abbreviations 3 1 Introduction 5 2 Aim and scope 5 3 Literature 6 4 Background: Comparative Indo-European linguistics 7 4.1 Old English in the Indo-European language family . 7 4.1.1 The Indo-European language family and the development of comparative Indo-European linguistics . 7 4.1.2 The Germanic language family . 9 4.1.3 The earliest attestation of Germanic . 10 4.2 Linguistic reconstruction . 11 4.2.1 Internal and external reconstruction . 11 4.2.2 Sound laws . 12 4.2.3 Analogy . 13 5 Conditions of the evolution of Old English morphology 14 5.1 Accent and stress . 14 5.2 Major sound changes from Proto-Indo-European to Old English . 15 5.2.1 Sound changes in stressed syllables . 15 5.2.2 Sound changes in weak syllables . 16 5.3 Morphophonemics . 17 5.3.1 Ablaut . 17 5.3.2 PIE root structure and the laryngeals . 18 6 Exemplification 20 6.1 Noun inflection . 20 6.1.1 a-Stems . 21 6.1.2 o¯ -Stems . 22 6.1.3 i-Stems . 23 6.1.4 u-Stems . 23 6.1.5 n-Stems . 24 1 6.1.6 Consonant stems and minor declensions . 24 6.2 Verb inflection . 25 6.2.1 Strong verbs . -

Agreement and Agree: Evidence from Germanic

Halldór Ármann Sigurðsson (LUND) Agree and Agreement: Evidence from Germanic Abstract This paper contains a descriptive overview of morphological agreement phenomena in the Germanic languages. In addition it studies the relation of overt agreement with the underlying LF relation of Agree. It is argued that CHOMSKY’S (2000, 2001a) Probe-Goal Approach is not well suited to account for the nature of abstract Agree, although it is descriptively adequate for some instances of morphological agreement. The central claim of the paper is that Agree reduces to Merge, i.e. it is a precondition on Merge (and an integrated part of it). Thus, whenever Merge applies, the possibility of agreement arises, i.e. a language has to make a parametric choice whether or not to signal each instance of Merge/Agree morphologically. Hence, the extreme variation of agreement across languages, even within a relatively limited and a closely related group of languages, such as the Germanic ones. The claim that Agree reduces to Merge is coined as the Agree Condition on Merge. It is claimed that this simple condition is a law of nature, hence of language. In addition, it is suggested that Move is driven by the needs of Merge/Agree, moving features to the edge of a category Y, such that the edge matches some features of the object with which Y merges. The approach pursued also supports the view that labelling and X’-theoretic conceptions are theoretical artifacts that should be dispensed with.1 1. Theoretical background CHOMSKY (2001a: 3) formulates his understanding of Agree as follows: We therefore have a relation Agree holding between α and β, where α has interpretable inflectional features and β has uninterpretable ones, which delete under Agree. -

Merging Verb Cluster Variation

Merging verb cluster variation Sjef Barbiers Hans Bennis Lotte Dros-Hendriks Universiteit Leiden Nederlandse Taalunie Meertens Instituut Abstract: In this paper we argue that verb clusters in Dutch varieties are merged and linearized in fully ascending (1-2-3) or fully descending (3-2-1) orders. We argue that verb clusters that deviate from these orders involve non-verbal material: adjectival participles, or nominal infinitives. As a result, our approach does not involve any unmotivated movements that are specific for verb clusters. Support for our analysis comes from (i) the interpretation of verb clusters; (ii) the fact that order variation depends on the types of verbs involved, which can be explained by selectional requirements of the verbs; and (iii) the geographic co-occurrence patterns of various orders. First, the 1-3-2 and 3-1-2 orders are argued to be ascending orders with a non-verbal 3. Indeed these orders occur in grammars that have ascending, rather than descending, verb clusters. Secondly, the 1-3-2 order is argued to be an interrupted V1-V2 cluster with a non-verbal 3. Indeed, this order is most common in the region where non-verbal material can interrupt the verb cluster. Our analysis of word order variation in verb clusters in terms of principles of grammar is further supported by an experiment in which we asked a large number of speakers distributed over the Dutch language area to rank all logicaly possible orders, including orders that are not common in their own variety of Dutch. The results demonstrate that speakers apply their syntactic knowledge to rank verb cluster orders that they do not use themselves. -

Study of Prefixes in Old English, Old High German and Gothic

Study of Prefixes in Old English, Old High German and Gothic Pranjal Srivastava1 Abstract— In this paper, we explore the meaning(s) of the on- prefix in Old English its corresponding prefixes in Gothic and Old High German. To do so, we compare and analyze the uncompounded (without prefix) and compounded (with prefix) meanings of strong Verbs listed in the book ’Vergleichendes und etymologisches Wörterbuch der germanischen starken Verben’ (a dictionary of Germanic Verbs and their forms in its daughter languages) and put forward possible meanings of the prefix and their possible sources. We observed three major meaning clusters: 1) The prefix denoted a reversal or weakening of the original uncompounded meaning 2) The prefix denoted a the action being done in a face-to-face capacity, to either positive or Fig. 1. The relationship between languages. negative effect 3) The prefix indicated a relationship between the Germanic Gothic Old English Old High German action done and the doer of the action. en- in- on- in(t)- and- and- on- in(t)- These results enable an in-depth study of the prefixes und- und- on- in(t)- that are derived from the original Proto-Germanic language. TABLE I Prefix correspondences across researched languages I. INTRODUCTION II. BACKGROUND The West Germanic (WGmc.) language family is the 2 The Germanic languages are a subfamily of the Indo- largest member of the three branches of the Germanic European family of languages. The last common ances- Language family (by native speakers) [1] [4]. Members tor of the Germanic languages, called Proto-Germanic of the WGmc. -

Grammaticalization in Germanic Languages

Grammaticalization in Germanic languages Martin Hilpert 1 Genetic and structural characteristics The Germanic languages represent a branch of the Indo-European language family that is traditionally traced back to a common ancestor, Proto-Germanic, which was spoken around 500 BC in the southern Baltic region (Henriksen and van der Auwera 1994). Three sub- branches, East-, West-, and North-Germanic, are recognized; of these, only the latter two survive in currently spoken languages. The now-extinct East-Germanic branch included Burgundian, Gothic, and Vandalic. The North-Germanic branch is represented by Danish, Faroese, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish. West-Germanic, which is less clearly identifiable as a single branch than North-Germanic, has given rise to Afrikaans, Dutch, English, Frisian, German, and Yiddish. The living Germanic languages have an extremely wide geographical distribution beyond the Proto-Germanic territory; besides colonial varieties (Afrikaans) and emigrant varieties (Texas German), many non-native varieties (Indian English) and creoles (Tok Pisin) are based on Germanic languages. Structurally, the Germanic languages are characterized by a pervasive loss of Proto-Indo- European inflectional categories. In comparison, English and Afrikaans exhibit the highest degree of analyticity, whereas German and Icelandic retain categories such as case, gender, and number on nouns and adjectives. For instance, Icelandic maintains an inflectional distinction between indicative and subjunctive across present and past forms of verbs (Thràinsson 1994). Several morphological and syntactic commonalities are worth noting. The Germanic languages share a morphological distinction between present and preterite in the verbal domain. Here, an older system of strong verbs, which form the past tense through ablaut (sing – sang), contrasts with a newer system of weak verbs that have a past tense suffix containing an alveolar or dental stop (play – played). -

Verb Second in Afrikaans: Is This a Unitary Phenomenon?1

19 VERB SECOND IN AFRIKAANS: IS THIS A UNITARY PHENOMENON? 1 Theresa Biberauer Department of Linguistics, University of Cambridge 1. Introduction The Verb Second (V2) phenomenon is a syntactic characteristic which features, to a greater or lesser extent, in all the Germanic languages. What it entails is the obligatory occurrence of finite verbs (Vfs) in clause-second position, following some initial (usually phrasal 2) constituent. The nature of the initial phrasal constituent is not restricted in any way, with subjects, objects, adverbials, negative phrases, and wh -phrases all qualifying as potential first position elements (see examples (1) - (5) below): 1. André het gister die storie geskryf André has yesterday the story written 2. Gister het André die storie geskryf Yesterday has André the story written 3. Die storie het André gister geskyrf The story has André yesterday written 4. Nêrens praat mense meer Latyn nie Nowhere speak people more Latin 5. Wat lees jy vandag? What read you today Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 34, 2002, 19-69 doi: 10.5774/34-0-34 20 The V2 phenomenon has received a lot of attention in the syntactic literature in general and in the literature on Germanic syntax and specific Germanic languages in particular 3. One Germanic language which has, however, never received more than a passing reference in these discussions is Afrikaans. The primary reason for this is that the V2 characteristics of its parent, Dutch, are well known, while the syntax of Afrikaans has been said to diverge very little from that of its parent (see inter alia Scholtz 1980: 91, Raidt 1983: 173, and Pheiffer 1989: 88). -

Agreement and Agree

Agree and Agreement - Evidence from Germanic Sigurðsson, Halldor Armann Published in: Focus on Germanic Typology 2004 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sigurðsson, H. A. (2004). Agree and Agreement - Evidence from Germanic. In W. Abraham (Ed.), Focus on Germanic Typology (pp. 61-103). Akademie Verlag. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 2004 In Focus on Germanic Typology, Studia Typologica 6/2004, ed. Werner Abraham, 59-99. Berlin: Akademieverlag. Halldór Ármann Sigurðsson (LUND) Agree and Agreement: Evidence from Germanic Abstract This paper contains a descriptive overview of morphological agreement phenomena in the Germanic languages. In addition it studies the relation of overt agreement with the underlying LF relation of Agree. -

Consonant and Vowel Gradation in the Proto-Germanic N-Stems Guus, Kroonen

Consonant and vowel gradation in the Proto-Germanic n-stems Guus, Kroonen Citation Guus, K. (2009, April 7). Consonant and vowel gradation in the Proto-Germanic n-stems. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14513 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14513 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Consonant and vowel gradation in the Proto-Germanic n-stems PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 7 april 2009 klokke 16:15 uur door GUUS JAN KROONEN geboren te Alkmaar in 1979 Promotor: Prof. dr. A.M Lubotsky Commissie: Prof. dr. F.H.H. Kortlandt Prof. dr. R. Lühr (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena) Dr. H. Perridon (Universiteit van Amsterdam) Prof. dr. A. Quak Þá er þeir Borssynir gengu með sævar strǫndu, fundu þeir tré tvau ok tóku upp tréin ok skǫpuðu af menn: gaf hinn fyrsti ǫnd ok líf, annarr vit ok hræring, þriði ásjónu ok málit ok heyrn ok sjón. Hár, Gylfaginning The Leiden theory explains religion as a disease of language and predicts the existence of God and other such parasitic mental constructs as artefacts of language. George van Driem, 2003 Table of contents Preface................................................................................................................................