An Investigation Into How Social Capital Influences Board Effectiveness Within the Context of Scottish Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T H E B a N K I

Today’s Squads Clydebank FC - Official Match Programme - Season 2014-15 - Issue No. 12.9 CLYDEBANK SHOTTS B.A. ROBERT HAMILTON GARY WHITE LIAM CAMPBELL PAUL McKANE SCOTT WALKER DOUGLAS MacKAY ANDY PATERSON GARRY CAMPBELL ROSS HARVIE PETER McMAHON JONATHON ALAN LIAM MUSHET ANDY IRVINE CHRIS WALKER PAUL BELL DAVID CRAWFORD GRAHAM MORT ROSS BRASH TOMMY MARTIN ANTON McDOWALL CRAIG McCREADY GARRY McSTAY JAMIE CAMPBELL CLARK RANKIN AUSTIN McCANN ANTHONY TRAYNOR IAN GOLD SALIM KOUIDER-ASSIA GRAEME RAMAGE JACK MARRIOTT REECE PEARSON JORDAN WHITE JORDAN SHELVEY ANDY CROSS JOE ANDREW STEPHEN GARDINER MANAGER Referee : DAVID LOWE PHIL BARCLAY TAM McDONALD Assistant Ref 1 : TONY KELLY ASS’T MANAGER MANAGER Assistant Ref 2 : LEE DIXON JOHN GIBSON BILLY McGHIE ASS’T MANAGER Today’s match ball sponsors are The COACHES STUART ALLISON Matchday Ground crew Ronnie Johnson , PAUL McANENAY Clydebank COACHES Stuart McSporran, Stewart McIlroy, Ian JACK STEEL McVicar, and Davie Brockett Snr GORDON ROBERTSON PHYSIO V ALLAN HAMILTON KIRSTY HUGHES T H E B A N K I E S A H E B T Shotts Bon Accord West Super Premier Division Clydebank FC Programme printed by Kenwil Print & Design 0141-776-8070 £1.50 Saturday 8th. Nov 2014 2.00pm Programme Contents Bankies Merchandise 3…Dressing Room Chat 5…Chairman’s Chat 7…Proud To Be A Bankie 9…What's Going On 10..Match Report...Lossiemouth CLYDEBANK FOOTBALL CLUB 12..Visitors Holm Park Clydebank - 07946 680812 15..Cods Quiz Page DIRECTORS Gordon Robertson (Chairman) 18..Results & Stats When you are at the game remember and check out Matt Bamford (Match Secretary) 20..Titan’s Bankies A-Z the Bankies shop in the blue hut. -

Scottish Sun Article

1S Friday, September 3, 2010 27 Tribute to bike hero MILITARY chiefs last night paid tribute to a ScotsNavy hero killed in ahorror bike smash. Petty Officer Jamie Adam, 28, died after he and cop Chris Bradshaw’s motorcycles crashed during the Manx Grand Prix on the Isle of Man. Chris, 39, of Tamworth, Staffordshire, lost his fight for life in hospital. Aspokesman for HMS Sultan, where Jamie, of Prestwick, had just com- pleted an air engineering course, said he had been “popular and profes- sional”, and added: “His tragic loss is felt deeply.” BIRTHDAY BOY ...Brian ICAESAR LIGHT Abronze Roman lan- TROOPS SET terndug up in afield near Sudbury, Suffolk, is the only one to have been FOR MARCH found in Britain. out Tartan Army drum lind youngster gets to try TO VICTORY BIG BANG THEORY ...b FRIENDS UNITED. .. TARTAN Army troops are on the From GRAEME DONOHOE Tartan Army Tartan Army Reporter, Euro 2012 march —and confident at the Gile Scotland will bounce back from last in Vilnius, Lithuania kids’ home month’s friendly defeat in Sweden. Refuse collection worker Brian THE Tartan Army carried out Mason hopes Craig Levein’s Brave- ahearts and minds mission hearts will deliver him the perfect birthday present. at an orphanage in Vilnius Brian, from Aber- yesterday —after local press deen, said: “I’m 50 warned our Scots fans are a on the day of the game, so I’m hoping SECURITY THREAT. Scotland will help Lithuanian media caused a me celebrate it stir about our fun-lovin’ fans properly. when they suggested more “I reckon theboys cops would have to be drafted will win 2-0 —no GIFT ...Carey hands over shirt problem. -

Ag/S5/19/18 Parliamentary Bureau Agenda for Meeting

AG/S5/19/18 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU AGENDA FOR MEETING ON TUESDAY 21 MAY 2019 12noon: Room Q1.03 1. Minutes (a) Draft minutes of 14 May 2019 (b) Matters arising. 2. Future business programme (PB/S5/19/75) 3. Referral of a legislative consent memorandum (PB/S5/19/76) 4. Referral of a Members’ Bill proposal (PB/S5/19/77) Date of next meeting— Tuesday 28 May 2019 @ 12noon RESTRICTED – POLICY PB/S5/19/MINS/17 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON 14 MAY 2019 AT 12 noon. Attending: Ken Macintosh (chair), Christine Grahame, Graeme Dey, Alexander Burnett, Neil Findlay, Patrick Harvie, Alex Cole-Hamilton, James Dornan (item 2), Ruth Maguire (item 2). Observing: Tom Arthur Apologies: Maurice Golden, Willie Rennie Officials present: Paul Grice, Tracey White, Irene Fleming, Catherine Fergusson, Lewis McNaughton, Kathryn Stewart, Joanne McNaughton, Jennifer Bell, Peter McGrath (item 2), Claire Menzies (item 2). 1. Item 1a: Minutes of last meeting — The minutes of 7 May 2019 were agreed. Item 1b: Matters arising — There were no matters arising. 2. Referral of a Bill at Stage 1 — James Dornan MSP, on behalf of the Local Government and Communities Committee, and Ruth Maguire MSP, on behalf of the Equalities and Human Rights Committee, joined the Bureau to discuss referral of the Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Bill. Following discussion, the Bureau agreed to recommend to the Parliament that the Local Government and Communities Committee be designated as lead committee for consideration of the Bill at Stage 1. 3. Future business programme — The Bureau agreed to recommend to the Parliament a programme of business for the weeks commencing 20 and 27 May 2019. -

Download the App Now

THE MAGAZINE OF THE LEAGUE MANAGERS ASSOCIATION ISSUE 40 | £7.50 VALUES, DISCIPLINE, SELF-BELIEF PHIL NEVILLE, ENGLAND WOMEN’S MANAGER EXCELLENCE THROUGH INSIGHT FROM THE EDITOR As this edition hits desks and doormats, the FIFA Women’s The League Managers Association, St. George’s Park, National Football World Cup 2019 will be well underway, with Phil Neville’s Centre, Newborough Road, Needwood, Lionesses aiming not only to top their third-place finish in Burton upon Trent, DE13 9PD The views and opinions expressed 2015, but to come away victorious. by contributors are their own and not necessarily those of the League Having won the SheBelieves Cup earlier this year, the side go to France Managers Association, its members, emboldened and ready to work their socks off, but Neville knows first hand officers or employees. Reproduction there needs to be something to counter the intense pressure of tournament in whole or in part without written football. “They need to breathe, to enjoy the experience and create memories permission is strictly prohibited. that will last a lifetime,” he says. www.leaguemanagers.com Neville leads his players with understanding and empathy, but as we discover in our cover feature, he has high expectations in terms of professionalism and work ethic and never dons kid gloves. “Very early on, I explained my vision and Editor Alice Hoey values to the players,” he says. “For six-to-eight months we reinforced our [email protected] core messages every day, the standards we expected, the intensity we wanted in training, our winning mentality.” Editor for LMA Sue McKellar [email protected] Of course, a winning mindset is about more than self-belief and discipline. -

Sample Download

DUNDEE UNITED ON THIS DAY JANUARY 11 Dundee United On This Day THURSDAY 1st JANUARY 2015 A great start to 2015 as United thump Dundee in the new year derby at Tannadice, in front of 13,000 fans. Stuart Armstrong deflects a Chris Erskine shot into the Dundee net in the first minute, and an Erskine strike and a Gary Mackay-Steven double make it 4-1 by half-time. Jaroslaw Fojut and Charlie Telfer add two more in the second half, and the 6-2 final score puts United third in the Premiership, just three points behind Aberdeen and two behind Celtic. WEDNESDAY 1st JANUARY 1913 Dumbarton are the new year’s day visitors at Tannadice, but, although a railway special brings 300 fans through from the west coast, The Dundee Evening Telegraph reports that very few of them make it to the game, presumably as a side effect of their new year celebrations. The Dumbarton players, on the other hand, show no sign of any hangover as they start brightly in a match full of chances, but Dundee Hibernian – as the club were called before changing their name to United – come back from 3-1 down to draw 3-3. THURSDAY 2nd JANUARY 1958 United beat East Stirling 7-0. Jimmy Brown and Wilson Humphries both grab doubles, and Allan Garvie, Willie McDonald and Joe Roy score once each. Twenty-year-old Aberdonian defender Ron Yeats makes his debut in the match. He features prominently for United for four seasons, before, in 1961, he’s sold for £30,000 to Liverpool, where he becomes hugely influential and plays over 450 games. -

The Big Scottish Football Quiz Answers

THE BIG SCOTTISH FOOTBALL QUIZ ANSWERS Round One: Scottish Football General Knowledge Round 1. Which of these Scottish league grounds is furthest north? a. Arbroath b. Brechin City c. Forfar Athletic d. Montrose 2. Who was the last team to win the Scottish Junior Cup that wasn’t Auchinleck Talbot? a. Pollok b. Hurlford United c. Glenafton Athletic d. Musselburgh Athletic 3. Which of these players made their senior Scotland debut first? a. David Weir b. Craig Burley c. Colin Hendry d. Paul Lambert 4. Willie Miller had is birthday on Saturday there. What birthday did he celebrate? a. 55th b. 60th c. 65th d. 70th 5. Who did Rangers beat in the quarter finals of the UEFA Cup in 2008 when they made the final? a. Sporting CP b. Werder Bremen c. Fiorentina d. Panathinaikos 6. Who is the only team apart from Hibernian or Glasgow City to appear in a Women’s Scottish Cup Final since 2015? a. Motherwell b. Celtic c. Spartans d. Forfar Farmington 7. Who did Celtic sign Leigh Griffiths from? a. Hibernian b. Livingston c. Dundee d. Wolverhampton Wanderers 8. Who did Andy Robertson make his senior Scotland debut against? a. Czech Republic b. Poland c. England d. Norway 9. What was the name of the fictional Scottish football team in the film A Shot at Glory? a. Inverleven FC b. Greendale Thistle c. Earls Park d. Kilnockie FC 10. Who won the first ever Scottish Challenge Cup in 1991? a. Dundee b. Ayr United c. Hamilton Academical d. Stenhousemuir Round Two: Scottish Cup Final Questions 11. -

Team Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Team checklist I have the complete set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976 Coventry City John McLaughlan Robert (Bobby) Lee Ken McNaught Malcolm Munro Coventry City Jim Pearson Dennis Rofe Jim Brogan Neil Robinson Steve Sims Willie Carr David Smallman David Tomlin Les Cartwright George Telfer Mark Wallington Chris Cattlin Joe Waters Mick Coop Ipswich Town Keith Weller John Craven Ipswich Town Steve Whitworth David Cross Kevin Beattie Alan Woollett Alan Dugdale George Burley Frank Worthington Alan Green Ian Collard Steve Yates Peter Hindley Paul Cooper James (Jimmy) Holmes Eric Gates Manchester United Tom Hutchison Allan Hunter Martin Buchan Brian King David Johnson Steve Coppell Larry Lloyd Mick Lambert Gerry Daly Graham Oakey Mick Mills Alex Forsyth Derby County Roger Osborne Jimmy Greenhoff John Peddelty Gordon Hill Derby County Brian Talbot Jim Holton Geoff Bourne Trevor Whymark Stewart Houston Roger Davies Clive Woods Tommy Jackson Archie Gemmill Steve James Charlie George Leeds United Lou Macari Kevin Hector Leeds United David McCreery Leighton James Billy Bremner Jimmy Nicholl Francis Lee Trevor Cherry Stuart Pearson Roy McFarland Allan Clarke Alex Stepney Graham Moseley Eddie Gray Anthony (Tony) Young Henry Newton Frank Gray David Nish David Harvey Middlesbrough Barry Powell Norman Hunter Middlesbrough Bruce Rioch Joe Jordan David Armstrong Rod Thomas - 3 Peter Lorimer Stuart Boam Colin Todd Paul Madeley Peter Brine Everton Duncan McKenzie Terry Cooper Gordon McQueen John Craggs Everton Paul Reaney Alan Foggon John Connolly Terry Yorath John Hickton Terry Darracott Willie Maddren Dai Davies Leicester City David Mills Martin Dobson Leicester City Robert (Bobby) Murdoch David Jones Brian Alderson Graeme Souness Roger Kenyon Steve Earle Frank Spraggon Bob Latchford Chris Garland David Lawson Len Glover Newcastle United Mick Lyons Steve Kember Newcastle United This checklist is to be provided only by Nigel's Webspace - http://cards.littleoak.com.au/. -

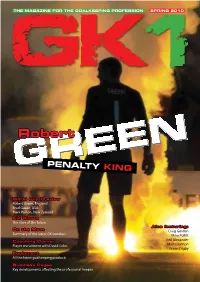

GK1 - FINAL (4).Indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2010 Robert PENALTY KING World Cup Preview Robert Green, England Brad Guzan, USA Mark Paston, New Zealand Kid Gloves The stars of the future Also featuring: On the Move Craig Gordon Summary of the latest GK transfers Mike Pollitt Coaching Corner Neil Alexander Player recruitment with David Coles Matt Glennon Fraser Digby Equipment All the latest goalkeeping products Business Pages Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper GK1 - FINAL (4).indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02 BPI_Ad_FullPageA4_v2 6/2/10 16:26 Page 1 Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. goalkeeper, with coaching features, With the greatest footballing show on Editor’s note equipment updates, legal and financial earth a matter of months away we speak issues affecting the professional player, a to Brad Guzan and Robert Green about the Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Director of World In Motion ltd summary of the key transfers and features potentially decisive art of saving penalties, stand out covering the uniqueness of the goalkeeper and hear the remarkable story of how one to a football team. We focus not only on the penalty save, by former Bradford City stopper from the crowd stars of today such as Robert Green and Mark Paston, secured the All Whites of New Craig Gordon, but look to the emerging Zealand a historic place in South Africa. talent (see ‘kid gloves’), the lower leagues is a magazine for the goalkeeping and equally to life once the gloves are hung profession. We actively encourage your up (featuring Fraser Digby). -

Darren Smith (Footballer, Born 1986)

Darren Smith (footballer, born 1986) All information for Darren Smith (footballer, born 1980)'s wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Pictures, videos, biodata, and files relating to Darren Smith (footballer, born 1980) are also acceptable encyclopedic sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darren_Smith_(footballer,_born_1980). The original version of this page is from Wikipedia, you can edit the page right here on Everipedia. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Darren Smith (born 6 December 1986) is a Scottish association football player who plays for Scottish Junior side Bonnyrigg Rose. Smith, who began his career with Hibernian, signed for Airdrie United in 2007. He was part of the Airdrie side who won the Scottish Challenge Cup in 2008.[1] Smith was dropped by manager Kenny Black soon afterwards, but was recalled when it was announced that Steven McDougall and Joe Cardle had signed pre-contract agreements with Dunfermline. [2]. Smith was released by Airdrie in 2010, and then spent a few months out of the game.[3] He signed for Albion Rovers on a sh Darren Smith (born 9 February 1965) is a former Australian rules footballer who played for Port Adelaide in the South Australian National Football League (SANFL) and Adelaide in the Australian Football League (AFL). Smith arrived in Adelaide from the Eyre Peninsula and after playing under-age football, he broke into the Port Adelaide seniors in 1984. He topped Port's goal-kicking in 1986 and 1987, with 49 and 71 goals respectively, ending the sequence of nine leading goal-kicker awards from Tim Evans Darren Smith (born 6 December 1986) is a Scottish footballer who plays for Scottish Junior side Bonnyrigg Rose. -

Annual Financial Review of Scottish Premier League Football Season 2009-10 Contents

www.pwc.co.uk Fighting for the future Scottish Premier League Football 22nd Annual Financial Review of Scottish Premier League football season 2009-10 Contents Introduction 3 Profit and loss 5 Balance sheet 16 Cashflow 22 Appendix one 2009/10 the season that was 39 Appendix two What the directors thought 41 Appendix three Significant transfer activity 2009/10 42 Appendix four The Scottish national team 43 compared to the previous season’s run in the Champions League group stage. Introduction Making reasonable adjustments for these items shows that the league generated an underlying loss of c£16m. Adjustments (£m) Headline profit 1 Less: exceptional profit adjustment (7) Less: Champions League profit adjustment (10) Welcome to our 22nd annual financial review £(16) of Scottish Premier League (SPL) football. Adjusted underlying turnover was c£156m, representing a fall of 6%, and the underlying operating loss was £6m with only the Old Firm and Dundee with both clubs’ results being boosted Back to black? United generating an operating profit by related parties forgiving £8m and In season 2009/10, the SPL posted its – every other club was loss-making at £1m of debt, respectively. These are fifth bottom-line profit in the past six this level. one-off items and don’t represent a seasons. On the face of it, this modest true flow of income for the clubs. £1m profit appears positive, given the It is therefore clear that the SPL clubs have not been immune to the impact ongoing turbulent economic climate, The season’s results were particularly of the recessionary environment. -

Maquetación 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Does managerial turnover affect football club share prices? Article Published Version Open Access Bell, A., Brooks, C. and Markham, T. (2013) Does managerial turnover affect football club share prices? Aestimatio, the IEB International Journal of Finance, 7. 02-21. ISSN 2173-0164 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/32210/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Publisher: Instituto de Estudios Bursátiles All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online E aestimatio, the ieb international journal of finance , 2013. 7: 02-21 L the ieb international journal of finance C © 2013 aestimatio , I T R A H C Does managerial turnover R A E S Affect Football Club Share Prices? E R Bell, Adrian R. Brooks, Chris Markham, Tom ̈ RECEIVED : 13 JANUARY 2013 ̈ ACCEPTED : 11 MARCH 2013 Abstract This paper analyses the 53 managerial sackings and resignations from 16 stock exchange listed English football clubs during the nine seasons between 2000/01 and 2008/09. The results demonstrate that, on average, a managerial sacking results in a post-announcement day market-adjusted share price rise of 0.3%, whilst a resignation leads to a drop in share price of 1% that continues for a trading month thereafter, cumulating in a negative abnormal return of over 8% from a trading day before the event. -

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Contents

Queen of the South Football Club SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Contents Welcome 1 League Match Sponsorship 2 Gold Match Ball Sponsorship 3 Silver Match Ball Sponsorship 4 Stadium Advertising 5 Executive Club Membership 6 Player Sponsorship 6 Match Mascot 7 Ballboy Sponsorship 7 Youth Team Sponsorship 8 Substitutes’ Board Sponsorship 9 Corporate Tannoy Announcements 9 Warm Up Kit Sponsorship 10 Website Advertising 10 Match Day Programme Advertising 11 Teamsheet Sponsorship 12 Season Ticket Sponsorship 12 Welcome Queen of the South Football Club is a Scottish professional football club founded in 1919 and located at Palmerston Park in Dumfries. They are o!cially nicknamed The Doonhamers, but usually referred to as Queens or QOS. The club has won national honours, winning the Division B Championship in 1950-51, the 2001-02 Second Division Championship and the 2002–03 Scottish Challenge Cup. Queens led Scotland’s top division up until New Year in season 1953-54 and Queens highest "nish in Scotland’s top division was 4th in season 1933-34. They reached their "rst major cup "nal in 2008 when they reached the "nal of the Scottish Cup, where they were runners-up to Glasgow Rangers. Season 2012-13 saw Queen of the South F.C. have one of their most successful seasons to date, winning the SFL Division 2 and the 2012/13 Ramsdens Cup. Season 2013-14 was a successful season with the team "nishing fourth in their return to the Championship and reaching the "rst ever Championship play o#s. This season will see Rangers FC, Heart of Midlothian FC and Hibernian FC all compete in the championship - Which is sure to make a highly entertaining and talked about league.