Abstract Survey of Invasive, Exotic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code of Federal Regulations GPO Access

9±16±97 Tuesday Vol. 62 No. 179 September 16, 1997 Pages 48449±48730 Briefings on how to use the Federal Register For information on briefings in Boston, MA, see the announcement on the inside cover of this issue. Now Available Online Code of Federal Regulations via GPO Access (Selected Volumes) Free, easy, online access to selected Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) volumes is now available via GPO Access, a service of the United States Government Printing Office (GPO). CFR titles will be added to GPO Access incrementally throughout calendar years 1996 and 1997 until a complete set is available. GPO is taking steps so that the online and printed versions of the CFR will be released concurrently. The CFR and Federal Register on GPO Access, are the official online editions authorized by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register. New titles and/or volumes will be added to this online service as they become available. http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr For additional information on GPO Access products, services and access methods, see page II or contact the GPO Access User Support Team via: ★ Phone: toll-free: 1-888-293-6498 ★ Email: [email protected] federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 16, 1997 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 General online information 202±512±1530; 1±888±293±6498 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), Single copies/back copies: by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Paper or fiche 512±1800 Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 Register Act (49 Stat. -

Agricultural Marketing Service, USDA § 201.2

SUBCHAPTER K—FEDERAL SEED ACT PART 201—FEDERAL SEED ACT LABELING IN GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 201.31a Labeling treated seed. 201.32 Screenings. 201.33 Seed in bulk or large quantities; seed DEFINITIONS for cleaning or processing. Sec. 201.34 Kind, variety, and type; treatment 201.1 Meaning of words. substances; designation as hybrid. 201.2 Terms defined. 201.35 Blank spaces. 201.36 The words ‘‘free’’ and ‘‘none.’’ ADMINISTRATION 201.3 Administrator. MODIFYING STATEMENTS 201.36a Disclaimers and nonwarranties. RECORDS FOR AGRICULTURAL AND VEGETABLE SEEDS ADVERTISING 201.4 Maintenance and accessibility. 201.36b Name of kind and variety; designa- 201.5 Origin. tion as hybrid. 201.6 Germination. 201.36c Hermetically-sealed containers. 201.7 Purity (including variety). 201.7a Treated seed. INSPECTION LABELING AGRICULTURAL SEEDS 201.37 Authorization. 201.38 [Reserved] 201.8 Contents of the label. 201.9 Kind. SAMPLING IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE ACT 201.10 Variety. 201.39 General procedure. 201.11 Type. 201.40 Bulk. 201.11a Hybrid. 201.41 Bags. 201.12 Name of kind and variety. 201.42 Small containers. 201.12a Seed mixtures. 201.43 Size of sample. 201.13 Lot number or other identification. 201.44 Forwarding samples. 201.14 Origin. 201.15 Weed seeds. PURITY ANALYSIS IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF 201.16 Noxious-weed seeds. THE ACT 201.17 Noxious-weed seeds in the District of Columbia. 201.45 Obtaining the working sample. 201.18 Other agricultural seeds. 201.46 Weight of working sample. 201.19 Inert matter. 201.47 Separation. 201.20 Germination. 201.47a Seed unit. 201.21 Hard seed or dormant seed. -

Seedimages Species Database List

Seedimages.com Scientific List (possibly A. cylindrica) Agropyron trachycaulum Ambrosia artemisifolia (R) not Abelmoschus esculentus Agrostemma githago a synonym of A. trifida Abies concolor Agrostis alba Ambrosia confertiflora Abronia villosa Agrostis canina Ambrosia dumosa Abronia villosum Agrostis capillaris Ambrosia grayi Abutilon theophrasti Agrostis exarata Ambrosia psilostachya Acacia mearnsii Agrostis gigantea Ambrosia tomentosa Acaena anserinifolia Agrostis palustris Ambrosia trifida (L) Acaena novae-zelandiae Agrostis stolonifera Ammi majus Acaena sanguisorbae Agrostis tenuis Ammobium alatum Acalypha virginica Aira caryophyllea Amorpha canescens Acamptopappus sphaerocephalus Alcea ficifolia Amsinckia intermedia Acanthospermum hispidum Alcea nigra Amsinckia tessellata Acer rubrum Alcea rosea Anagallis arvensis Achillea millifolium Alchemilla mollis Anagallis monellii Achnatherum brachychaetum Alectra arvensis Anaphalis margaritacea Achnatherum hymenoides Alectra aspera Andropogon bicornis Acmella oleracea Alectra fluminensis Andropogon flexuosus Acroptilon repens Alectra melampyroides Andropogon gerardii Actaea racemosa Alhagi camelorum Andropogon gerardii var. Adenostoma fasciculatum Alhagi maurorum paucipilus Aegilops cylindrica Alhagi pseudalhagi Andropogon hallii Aegilops geniculata subsp. Allium canadense Andropogon ternarius geniculata Allium canadense (bulb) Andropogon virginicus Aegilops ovata Allium cepa Anemone canadensis Aegilops triuncialis Allium cernuum Anemone cylindrica Aeginetia indica Allium fistulosum Anemone -

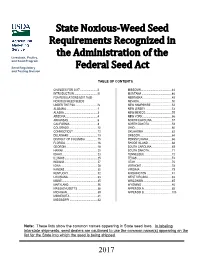

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Federal Seed Act

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Livestock, Poultry, and Seed Program Seed Regulatory Federal Seed Act and Testing Division TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGES FOR 2017 ........................ II MISSOURI ........................................... 44 INTRODUCTION ................................. III MONTANA .......................................... 46 FSA REGULATIONS §201.16(B) NEBRASKA ......................................... 48 NOXIOUS-WEED SEEDS NEVADA .............................................. 50 UNDER THE FSA ............................... IV NEW HAMPSHIRE ............................. 52 ALABAMA ............................................ 1 NEW JERSEY ..................................... 53 ALASKA ............................................... 3 NEW MEXICO ..................................... 55 ARIZONA ............................................. 4 NEW YORK ......................................... 56 ARKANSAS ......................................... 6 NORTH CAROLINA ............................ 57 CALIFORNIA ....................................... 8 NORTH DAKOTA ............................... 59 COLORADO ........................................ 10 OHIO .................................................... 60 CONNECTICUT .................................. 12 OKLAHOMA ........................................ 62 DELAWARE ........................................ 13 OREGON............................................. 64 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ................. 15 PENNSYLVANIA................................ -

Alien and Invasive Species Lists, 2014

STAATSKOERANT, 1 AUGUSTUS 2014 No. 37886 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS No. 599 1 August 2014 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT: BIODIVERSITY ACT 2004 (ACT NO, 10 OF 2004) ALIEN AND INVASIVE SPECIES LISTS, 2014 I, Bomo Edith Edna Molewa, Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs, hereby publishes the following Alien and Invasive Species lists in terms of sections 66(1), 67(1), 70(1)(a), 71(3) and 71A of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004 (Act No. 10 of 2004) as set out in the Schedule hereto. MS. BOMO EDITH EDNA MOLEWA MINISTER OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37886 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 AUGUST 2014 NOTICES AND LISTS IN TERMS OF SECTIONS 66(1), 67(1), 70(1)(a), 71(3) and 71A Notice 1:Notice in respect of Categories 1a, 1 b, 2 and 3, Listed Invasive Species, in terms of which certain Restricted Activities are prohibited in terms of section 71A(1); exempted in terms of section 71(3); require a Permit in terms of section 71(1) Notice 2:Exempted Alien Species in terms of section 66(1). Notice 3:National Lists of Invasive Species in terms section 70 1 . 559 species /croups of species List 1: National List of Invasive Terrestrial and Fresh-water Plant Species 379 List 2: National List of Invasive Marine Plant Species 4 List 3: National List of Invasive Mammal Species 41 List 4: National List of Invasive Bird Species 24 List 5: National List of Invasive Reptile Species 35 List 6: National List of Invasive Amphibian -

Monitoring Lake Ice Seasons in Southwest Alaska with Modis Images

MONITORING LAKE ICE SEASONS IN SOUTHWEST ALASKA WITH MODIS IMAGES Page Spencer, Chief of Natural Resources Lake Clark National Park and Preserve 240 W 5th Ave Anchorage, Alaska 99501 [email protected] Amy E. Miller, Ecologist National Park Service, Southwest Alaska Network 240 W 5th Ave Anchorage, Alaska 99501 [email protected] Bradley Reed. Associate Program Coordinator U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Reston, VA 20191 [email protected] Michael Budde, Geographer USGS Center for Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Sioux Falls, SD 57198 [email protected] ABSTRACT Impacts of global climate change are expected to result in greater variation in the seasonality of snowpack, lake ice, and vegetation dynamics in southwest Alaska. All have wide-reaching physical and biological ecosystem effects in the region. We used Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Rapidfire browse images, snow cover extent, and vegetation index products for interpreting interannual variation in the duration and extent of snowpack, lake ice, and vegetation dynamics for southwest Alaska. The approach integrates multiple seasonal metrics across large ecological regions. The general annual pattern of the lake ice season in southwest Alaska begins as water cools when fall storms sweep in from the North Pacific. Ice forms on high altitude or small lakes by Oct/Nov, with larger lakes usually freezing over by Dec/Jan. Warm mid-winter storms often hit the study area, bringing wind, rain and melting temperatures that result in several inches of water on the ice or partial break-up of the ice pack. The return of cold, still Arctic high pressure refreezes the lakes until spring break-up in April and May. -

Hunting / Unit 15 Kenai

Hunting / Unit 15 Kenai 7\RQHN *LUGZRRG +RSH 1LNLVNL .HQDL 6WHUOLQJ &RRSHU /DQGLQJ 0RRVH3DVV 6ROGRWQD .DVLORI &ODP*XOFK 1LQLOFKLN 6HZDUG $QFKRU3RLQW +RPHU 6HOGRYLD 1DQZDOHN 3RUW*UDKDP Federal Public Lands Open to Subsistence Use 70 2014/2016 Federal Subsistence Wildlife Regulations Unit 15 / Hunting (See Unit 15 Kenai map) Unit 15 consists of that portion of the Kenai Peninsula and adjacent islands draining into the Gulf of Alaska, Cook Inlet, and Turnagain Arm from Gore Point to the point where longitude line 150°00' W. crosses the coastline of Chickaloon Bay in Turnagain Arm, including that area lying west of longitude line 150°00' W. to the mouth of the Russian River; then southerly along the Chugach National Forest boundary to the upper end of Upper Russian Lake; and including the drainages into Upper Russian Lake west of the Chugach National Forest boundary. Unit 15A consists of that portion of Unit 15 north of the the north shore of Tustumena Lake, Glacier Creek, and north bank of the Kenai River and the north shore of Skilak Tustumena Glacier. Lake. Unit 15C consists of the remainder of Unit 15. Unit 15B consists of that portion of Unit 15 south of the north bank of the Kenai River and the north shore of Skilak Lake, and north of the north bank of the Kasilof River, Special Provisions ● The Skilak Loop Wildlife Management Area is ● Taking a red fox in Unit 15 by any means other than a closed to subsistence taking of wildlife, except that steel trap or snare is prohibited. grouse, ptarmigan, and hare may be taken only from ● Bait may be used to hunt black bear between April 15 October 1 - March 1 by bow and arrow only. -

Restoring Old Cabins on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge by Molly Slocum

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 5, No. 21 • May 30, 2003 Restoring old cabins on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge by Molly Slocum Midnight, June 21st you are sitting on the shore of place to enjoy the warm, sunny spring days than out- Lake Tustumena near Andrew Berg’s cabin. The colors doors next to a lake beneath the great blue sky. of twilight surround you, painting the lake and moun- I recently spent a weekend on Tustumena Lake as- tains with pink, blue, and lavender hues. The only sessing the condition of various cabins. We will be sounds reaching your ears are the water lapping at the restoring another of Andrew Berg’s cabins, which was sand and the wind rustling through the treetops. The built in 1902. Andrew Berg was a big game guide, and year could be 1895; you are on a hunting or fishing fish and game officer. After restoration, the cabinwill trip, and you are now relaxing after a day of hiking be exactly the same as it was before; no changes will in the high country. Or it could be 2003, and you are be made to the original design. enjoying a peaceful summer solstice retreat. It is a shame to visit these historical places and find The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge offers unique them defaced with graffiti carved into the old logs and backcountry experiences with many historic cabins. trash littering the inside and the ground around the Over the years cabins were built around the Kenai outside of the structures. This shows a lack of respect Peninsula to support activities such as hunting, fish- for people who lived here before us, who worked hard ing, trapping, and mining, as well as for year-round for their food and living. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge

2012 Interim Fire Management Plan: Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Kenai National Wildlife Refuge 2012 Interim FIRE MANAGEMENT PLAN KENAI NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Interim FIRE MANAGEMENT PLAN Revised May 2012 (05/25/2012) 2012 Interim Fire Management Plan: Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Table of Contents 1.1 Purpose of the Fire Management Plan ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 General description of the Area in the FMP ................................................................................ 9 1.3 Significant Values to Protect ...................................................................................................... 13 1.3.1 Special Values of the Kenai NWR ...................................................................................... 14 1.4 Effects of Climate on Biotic Composition ................................................................................. 17 2.0 POLICY, LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING AND PARTNERSHIPS ................................ 17 2.1 Federal Interagency Wildland Fire Policy ................................................................................. 17 2.1.1 Federal Wildland Fire Cost Effectiveness Policy ............................................................... 19 2.1.2 National Fire Plan ............................................................................................................... 19 2.1.3 Department of Interior (DOI) Fire Policy .......................................................................... -

Unit 15A North Ofthe Sterling Highway

State restricted areas: 1 Skilak Loop Management Area - bounded by a line beginning at the easternmost junction of the Sterling Highway and the Skilak Loop Road (Mile 58), then due south to the south bank of the 5 Kenai River, then southerly along the south bank of the Kenai River to its confluence with Russian River Closed Area Skilak Lake, then westerly along the north shore of Skilak Lake to Lower Skilak Lake that area within 150 yards, and including the river, campground, then northerly along the Lower Skilak Lake campground road and from the outlet of Lower Russian Lake downstream to the Skilak Loop Road to its westernmost junction with the Sterling Highway the Russian River/Kenai River confluence, then (Mile 75.1), then easterly along the Sterling Highway to the point of origin, continuing downstream 700 yards along the bank is closed to hunting and trapping except that moose may be taken of the Kenai River, is closed to hunting by permit only, and small game may be taken from October 1 - for the months of June and July. March 1 by bow and arrow only, and by standard .22 rimfire or shotgun in that portion of the area west of a line from 6 the access road from the Sterling Highway to Kelly Anchor River/Fritz Creek Lake, the Seven Lakes Trail, and the access road restricted to off-road vehicles less than 1,000 from Engineer Lake to Skilak Lake Road, and north pounds dry weight on designated trails only, of Skilak Lake Road, during each weekend from however off-road vehicles less than 1000 pounds Nov 1 - Dec 31 including the Friday following dry weight may beused to retrieve downed animals Thanksgiving Day, by youth hunters 16 years old during lawful hunting seasons. -

El Género Prosopis, Valioso Recurso Forestal De Las Zonas Áridas Y Semiáridas De América, Asia Y Africa

EL GÉNERO PROSOPIS, VALIOSO RECURSO FORESTAL DE LAS ZONAS ÁRIDAS Y SEMIÁRIDAS DE AMÉRICA, ASIA Y AFRICA. Santiago Barros. Ingeniero Forestal. Instituto Forestal, Chile. [email protected] RESUMEN El género Prosopis, familia Leguminosae o Fabaceae, subfamilia Mimosoideae, está presente en forma natural en las zonas áridas y semiáridas de África, América y Asia. Consta de 44 especies, arbustivas y arbóreas, que taxonómicamente han sido divididas en 5 secciones. Tres especies son nativas de Asia, una de África y las restantes cuarenta de América, principalmente Sudamérica. Se las conoce con diferentes nombre vernáculos locales; en América, algarrobo, mezquite, Mesquite, Screwbean. Son especies multipropósito, la mayoría espinosas, alrededor de la mitad de ellas superan los 7 m de altura y varias llegan a 15 y 20 m de altura. Son resistentes a extremas condiciones de sitio; sequía, calor, salinidad en el suelo, y todas ellas son fijadoras de nitrógeno. Sus principales productos son combustible, en forma de leña y carbón de muy buena calidad, y forraje, por medio de su follaje y brotes tiernos y principalmente sus frutos. Según la especie se puede obtener madera para estructuras e incluso para aserrío, de gran calidad para muebles, parqué y otros usos, alimento humano en algunos casos, tinturas, curtientes, gomas, fibras y productos medicinales. Estas características hacen de estas especies un recurso de mucho interés para zonas áridas y semiáridas, razón por la que se las ha introducido mediante plantaciones fuera de sus regiones de distribución natural. Especies como Prosopis juliflora y P. pallida, de América han sido introducidas en el NE de Brasil, en diversos países de África y Asia, y en Australia. -

BAER Final Report

BAER Final Report Invasive Plant Monitoring Following 2004 Fires USFWS National Wildlife Refuges – Alaska Region Collection site. Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge. Helen Cortés-Burns and Matt Carlson Alaska Natural Heritage Program Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street Anchorage, Alaska 99501 Report funded by and prepared for: USFWS, Alaska Regional Office February 2006 - 1 - ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................................- 4 - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................- 5 - INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................- 6 - TREATMENT SPECIFICATION ..................................................................................................................................- 6 - LOGISTICS, SAMPLING PROTOCOLS, AND DATA ANALYSIS .....................................................................................- 7 - Pre-fieldwork: logistics........................................................................................................................................- 7 - Fieldwork: methodology......................................................................................................................................-