An Analysis of Drugs in Used Syringes from Sentinel European Cities Results from the ESCAPE Project, 2018 and 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cathinones in Seized Materialsd

Recommended methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cathinones in Seized Materials (Revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES Photo credits:UNODC Photo Library; UNODC/Ioulia Kondratovitch; Alessandro Scotti. Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cathinones in Seized Materials (Revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 Note Operating and experimental conditions are reproduced from the original reference materials, including unpublished methods, validated and used in selected national laboratories as per the list of references. A number of alternative conditions and substitution of named commercial products may provide comparable results in many cases. However, any modification has to be validated before it is integrated into laboratory routines. ST/NAR/49/REV.1 Original language: English © United Nations, March 2020. All rights reserved, worldwide. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of names of firms and commercial products does not imply the endorse- ment of the United Nations. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Laboratory and Scientific Section of the UNODC (LSS, headed by Dr. Justice Tettey) wishes to express its appreciation and thanks to Dr. -

Free PDF Download

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2019; 23: 3-15 Use of cognitive enhancers: methylphenidate and analogs J. CARLIER1, R. GIORGETTI2, M.R. VARÌ3, F. PIRANI2, G. RICCI4, F.P. BUSARDÒ2 1Unit of Forensic Toxicology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy 2Section of Legal Medicine, Universita Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy 3National Centre on Addiction and Doping, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy 4School of Law, University of Camerino, Camerino, Italy Abstract. – OBJECTIVE: In the last decades, phenidate analogs should be undertaken to re- several cognitive-enhancing drugs have been duce the uprising threat, and education efforts sold onto the drug market. Methylphenidate and should be made among high-risk populations. analogs represent a sub-class of these new psy- choactive substances (NPS). We aimed to re- Key Words: view the use and misuse of methylphenidate and Cognitive enhancers, Methylphenidate, Ritalin, Eth- analogs, and the risk associated. Moreover, we ylphenidate, Methylphenidate analogs, New psycho- exhaustively reviewed the scientific data on the active substances. most recent methylphenidate analogs (methyl- phenidate and ethylphenidate excluded). MATERIALS AND METHODS: Literature Introduction search was performed on methylphenidate and analogs, using specialized search engines ac- cessing scientific databases. Additional reports Consumption of various pharmaceutical drugs were retrieved from international agencies, in- by healthy individuals in an attempt to improve stitutional websites, and drug user forums. cognitive faculties is on the rise, whether for aca- RESULTS: Methylphenidate/Ritalin has been demic or recreational purposes1. These substances used for decades to treat attention deficit disor- are stimulants that preferentially target the cate- ders and narcolepsy. More recently, it has been used as a cognitive enhancer and a recreation- cholamines of the prefrontal cortex of the brain to al drug. -

Endogenous Metabolites: JHU NIMH Center Page 1

S. No. Amino Acids (AA) 24 L-Homocysteic acid 1 Glutaric acid 25 L-Kynurenine 2 Glycine 26 N-Acetyl-Aspartic acid 3 L-arginine 27 N-Acetyl-L-alanine 4 L-Aspartic acid 28 N-Acetyl-L-phenylalanine 5 L-Glutamine 29 N-Acetylneuraminic acid 6 L-Histidine 30 N-Methyl-L-lysine 7 L-Isoleucine 31 N-Methyl-L-proline 8 L-Leucine 32 NN-Dimethyl Arginine 9 L-Lysine 33 Norepinephrine 10 L-Methionine 34 Phenylacetyl-L-glutamine 11 L-Phenylalanine 35 Pyroglutamic acid 12 L-Proline 36 Sarcosine 13 L-Serine 37 Serotonin 14 L-Tryptophan 38 Stachydrine 15 L-Tyrosine 39 Taurine 40 Urea S. No. AA Metabolites and Conjugates 1 1-Methyl-L-histidine S. No. Carnitine conjugates 2 2-Methyl-N-(4-Methylphenyl)alanine 1 Acetyl-L-carnitine 3 3-Methylindole 2 Butyrylcarnitine 4 3-Methyl-L-histidine 3 Decanoyl-L-carnitine 5 4-Aminohippuric acid 4 Isovalerylcarnitine 6 5-Hydroxylysine 5 Lauroyl-L-carnitine 7 5-Hydroxymethyluracil 6 L-Glutarylcarnitine 8 Alpha-Aspartyl-lysine 7 Linoleoylcarnitine 9 Argininosuccinic acid 8 L-Propionylcarnitine 10 Betaine 9 Myristoyl-L-carnitine 11 Betonicine 10 Octanoylcarnitine 12 Carnitine 11 Oleoyl-L-carnitine 13 Creatine 12 Palmitoyl-L-carnitine 14 Creatinine 13 Stearoyl-L-carnitine 15 Dimethylglycine 16 Dopamine S. No. Krebs Cycle 17 Epinephrine 1 Aconitate 18 Hippuric acid 2 Citrate 19 Homo-L-arginine 3 Ketoglutarate 20 Hydroxykynurenine 4 Malate 21 Indolelactic acid 5 Oxalo acetate 22 L-Alloisoleucine 6 Succinate 23 L-Citrulline 24 L-Cysteine-glutathione disulfide Semi-quantitative analysis of endogenous metabolites: JHU NIMH Center Page 1 25 L-Glutathione, reduced Table 1: Semi-quantitative analysis of endogenous molecules and their derivatives by Liquid Chromatography- Mass Spectrometry (LC-TripleTOF “or” LC-QTRAP). -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

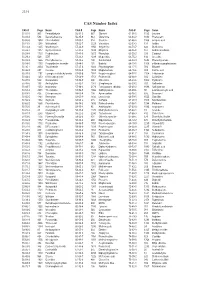

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Download Product Insert

PRODUCT INFORMATION Cathinone Analytical Standards Panel Item No. 31616 Storage: -20°C Stability: ≥2 years Laboratory Procedures Uncap each vial to be used. Add 500 µl of methanol to each vial. This will provide a 200 µg/ml standard solution for each analyte. Re-cap the vials and place plate on a plate mixer or vortexer. Mix for a minimum of 15 minutes to ensure full reconstitution. The plate included in this panel contains a residual amount of glycerol to aid in the reconstitution of the analyte in methanol. Recovery in methanol has been validated for all analytes on the plate. Recovery from other solvents has not been verified. Description The Cathinone Analytical Standards Panel contains 239 analytical reference materials and standards categorized as cathinones and cathinone metabolites. These compounds are supplied at 100 μg/well in a 96-well plate format for rapid screening or cataloging. The plate included in this panel contains a residual amount of glycerol to aid in the reconstitution of the analyte in methanol. Recovery in methanol has been validated for all analytes on the plate. Recovery from other solvents has not been verified. Please review the product insert for a full list of targets. The Cathinone Analytical Standards Panel contains compounds regulated as Schedule I compounds in the United States and is regulated as a Schedule I item. This product is intended for research and forensic applications. Panel Contents Plate Well Contents Item Number Molecular Formula CAS Number 1 A1 Unused 1 A2 (−)-(S)-Cathinone (hydrochloride) -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

3-7? CHEMICAL IONIZATION (CI) GC/MS ANALYSIS OF UNDERIVATIZED AMPHETAMINES FOLLOWED BY CHIRAL DERIVATIZATION TO IDENTIFY d AND 1-ISOMERS WITH ION TRAP MASS SPECTROMETRY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE (Pharmacology) By John A. Tarver B.S.,B.A. May, 1991 Tarver, John A. Chemical Ionization (CI) GC/MS Analysis of Underivatized Amphetamines Followed by Chiral Derivatiza- tion to Identify d and 1-Isomers with Ion Trap Mass Spectro- metry. Master of Science (Biomedical Sciences), May, 1991, 26 pp., 9 figures, bibliography, 20 titles. An efficient two step procedure has been developed using CI GC/MS for analyzing amphetamines and related compounds. The first step allows the analysis of underiv- atized amphetamines with the necessary sensitivity and specificity to give spectral identification, including differentiation between methamphetamine and phentermine. The second step involves preparing a chiral derivative of the extract to identify d and 1-isomeric composition. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.......... ... .. .. .......... iv INTRODUCTION .1........................... EXPERIMENTAL MATERIALS ...--- - - - - ----... -....-..... 15 METHODS --------------------.---...... 15 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ...-..-..................... 17 CONCLUSION - - - - - -- - - - - --- - --- . - . 23 APPENDIX......... ---. -----....-.-. ----.. -........ 24 REFERENCES ----------------------------.. --. ...---.. 28 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS -

New Drugs in Europe, 2012 Europe, in Drugs New

ISSN 1977-7841 New drugs in Europe, 2012 EMCDDA–Europol 2012 Annual Report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA 2012 New drugs in Europe, 2012 EMCDDA–Europol 2012 Annual Report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA In accordance with Article 10 of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA on the information exchange, risk assessment and control of new psychoactive substances Legal notice This publication of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is protected by copyright. The EMCDDA accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of the data contained in this document. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the EMCDDA’s partners, the EU Member States or any institution or agency of the European Union or European Communities. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Europe Direct is a service to help you find answersto your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 ISBN 978-92-9168-650-6 doi:10.2810/99367 © European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2013 Cais do Sodré, 1249-289 Lisbon, Portugal Tel. +351 211210200 • [email protected] • www.emcdda.europa.eu © Europol, 2013 Eisenhowerlaan 73, 2517 KK, The Hague, the Netherlands Tel. -

TURKEY MINISTRY of INTERIOR TURKISH NATIONAL POLICE Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime Department

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF INTERIOR TURKISH NATIONAL POLICE Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime Department 2014 NATIONAL REPORT (2013 data) TO THE EMCDDA by the Reitox National Focal Point TURKEY New Development, Trends and in-depth information on selected issues TURKISH MONITORING CENTRE FOR DRUGS AND DRUG ADDICTION (TUBİM) REITOX 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... 2 TURKISH NATIONAL FOCAL POINT STAFF PREPARING THE REPORT ........................... 7 DATA PROVIDING AGENCIES AND AGENCY REPRESENTATIVES ................................... 8 PREFACE .............................................................................................................................. 11 ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. 13 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 15 NEW DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS ................................................................................ 29 SECTION 1 ............................................................................................................................ 29 DRUG POLICY: LAWS, STRATEGIES, AND ECONOMIC ANALYSES ............................... 29 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 29 1.2. Legal Framework -

Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances Joshua Zolton Seither [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-25-2018 Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances Joshua Zolton Seither [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006565 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Seither, Joshua Zolton, "Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3823. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3823 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida APPLICATION OF HIGH RESOLUTION MASS SPECTROMETRY FOR THE SCREENING AND CONFIRMATION OF NOVEL PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in CHEMISTRY by Joshua Zolton Seither 2018 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Joshua Zolton Seither, and entitled Application of High- Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Piero Gardinali _______________________________________ Bruce McCord _______________________________________ DeEtta Mills _______________________________________ Stanislaw Wnuk _______________________________________ Anthony DeCaprio, Major Professor Date of Defense: April 25, 2018 The dissertation of Joshua Zolton Seither is approved. -

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition) July 1, 2019. This project was supported by Grant No. G1799ONDCP03A, awarded by the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Office of National Drug Control Policy or the United States Government. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Please contact NAMSDL at [email protected] or (703) 229-4954 with any questions about the Model Language. This document is intended for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or opinion. Headquarters Office: NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG 1 LAWS, 1335 North Front Street, First Floor, Harrisburg, PA, 17102-2629. Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)1 Table of Contents 3 Policy Statement and Background 5 Highlights 6 Section I – Short Title 6 Section II – Purpose 6 Section III – Synthetic Cannabinoids 13 Section IV – Substituted Cathinones 19 Section V – Substituted Phenethylamines 23 Section VI – N-benzyl Phenethylamine Compounds 25 Section VII – Substituted Tryptamines 28 Section VIII – Substituted Phenylcyclohexylamines 30 Section IX – Fentanyl Derivatives 39 Section X – Unclassified NPS 43 Appendix 1 Second edition published in September 2018; first edition published in 2014. Content in red bold first added in third edition. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens.