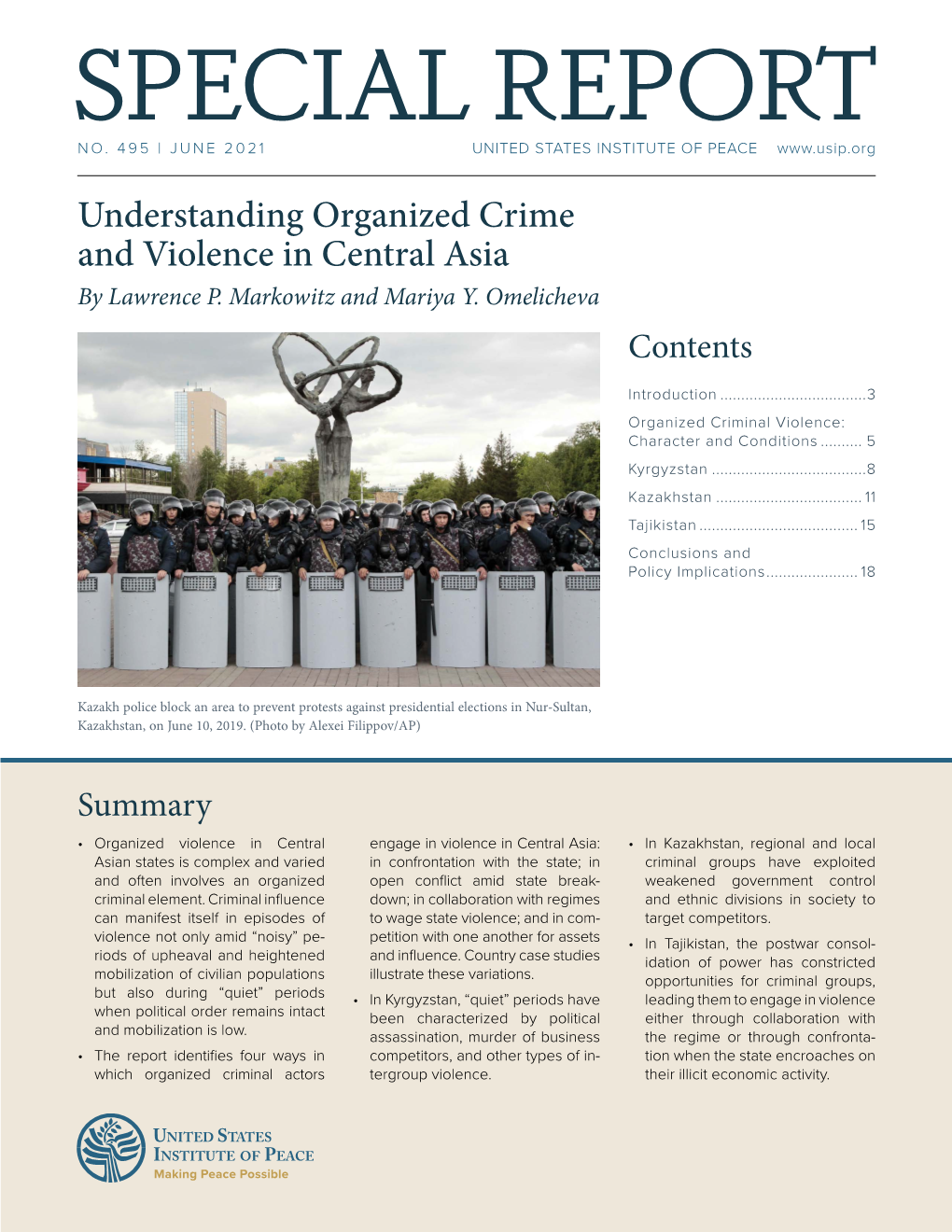

Understanding Organized Crime and Violence in Central Asia Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rising Sinophobia in Kyrgyzstan: the Role of Political Corruption

RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DOĞUKAN BAŞ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES SEPTEMBER 2020 Approval of the thesis: RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION submitted by DOĞUKAN BAŞ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Eurasian Studies, the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Dean Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT Head of Department Eurasian Studies Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL Supervisor Political Science and Public Administration Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT (Head of the Examining Committee) Middle East Technical University International Relations Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL (Supervisor) Middle East Technical University Political Science and Public Administration Assist. Prof. Dr. Yuliya BILETSKA Karabük University International Relations I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Doğukan Baş Signature : iii ABSTRACT RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION BAŞ, Doğukan M.Sc., Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL September 2020, 131 pages In recent years, one of the major problems that Kyrgyzstan witnesses is rising Sinophobia among the local people due to problems related with increasing Chinese economic presence in the country. -

The Kumtor Gold Mine and the Rise Of

Central Asia Economic Papers No. 16 August 2015 The Kumtor Gold Mine and the Rise of Resource Nationalism in Kyrgyzstan Matteo Fumagalli Key points Matteo Fumagalli is an Associate Professor in the Department of The mining sector has become the battleground on which the International Relations at Central Kyrgyz authorities, the opposition, the local communities and European University in Budapest (Hungary). His work lies at the the mining companies, defend their interests. intersection of identity politics There is more than ‘just’ economics to resource nationalism and ethnic conflict and the poli- tics of natural resources in Asia. and the Kumtor controversy: Symbolic politics matters as Recent and forthcoming works include articles in East European much, and complicates matters further. Politics, Electoral Studies, the Political instability, unrest, and constant calls for renegotiating Journal of Eurasian Studies, Eu- rope-Asia Studies, Ethnopolitics, contracts with foreign mining companies have already tattered and the International Political the country’s image as an investment destination. Science Review. His monograph on State Violence and Popular Resource nationalism in the mining sector proceeds in tides Resistance in Uzbekistan is forth- coming with Routledge (2016). whose timing appears not to be aligned to the trends in global commodity prices. The opinions expressed here are those of the author only and do not represent the Central Asia Program. CENTRAL ASIA ECONOMIC PAPERS No. 16, August 2015 Kyrgyzstan’s mining sector has become the battleground on which a number of players, namely the government, the opposition, local communities, and transnational corporations, defend their interests. No other site illustrates this point more than the country’s most prized asset, namely the gold mine at Kumtor, located some 350 kilometers south-east of the capital city of Bishkek. -

Introduction

24th Deutsche Schule Athen Model United Nations | 22nd-24th October 2021 Forum: Special Political and Decolonization Committee (GA4) Issue: The current political situation in Kyrgyzstan Student Officer: Chris Moustakis Position: Main Chair INTRODUCTION “A country without solid borders is like a house without solid walls – it is bound to collapse”. Kyrgyzstan is a nation located in Central Asia. It is bordered by Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China. Its capital and largest city is Bishkek. Surprisingly, despite the state of solitude that one would assume the nation had throughout history (primarily due to its mountainous terrain and location), it has hosted countless civilizations throughout history, albeit temporarily. It served as a crossroads, as it was part of the Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting the East and the West. On the 31st of August 1991, Kyrgyzstan declared independence from Moscow and formed a democratic government. It then attained sovereignty as a nation state, following the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. Ever since then, Kyrgyzstan has remained (at least officially) a unitary presidential republic. Despite this, the nation itself hasn’t been stable since independence. It undergoes ethnic disputes, revolts, transitional governments, political conflict and even economic crisis. To top it all off, on the 28th of April 2021 began a border conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The reason for this is rather debatable, as there are multiple theories. Figure 1: A map of the area of Kyrgyzstan and its neighboring nations.1 As the situation was addressed by Russia, the nation is “without leadership” and “chaotic”. It is undeniable that Kyrgyzstan has not had political stability ever since its independence. -

IFES Faqs Elections in Kyrgyzstan: 2021 Early Presidential Election

Elections in Kyrgyzstan 2021 Early Presidential Election Frequently Asked Questions Europe and Eurasia International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | USA | www.IFES.org January 8, 2021 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 What is the current political context, and what is at stake in these elections? ........................................... 1 What is the current form of government? ................................................................................................... 2 What is the term of the office of the president, and what is the president’s role? ..................................... 2 Who are the candidates? .............................................................................................................................. 2 Who is eligible to run as a candidate? .......................................................................................................... 3 What are the nomination and registration procedures for presidential candidates? ................................. 3 What is the campaign and electoral timeline? ............................................................................................. 4 Who is eligible to vote, and how many voters are registered to vote? ........................................................ 4 What are the campaign expenditure and donation limits? ......................................................................... -

OSW Commentary

OSW Commentary CENTRE FOR EASTERN STUDIES NUMBER 359 29.10.2020 www.osw.waw.pl Kyrgyzstan in the aftermath of revolution Mariusz Marszewski, Krzysztof Strachota On 15 October Kyrgyzstan’s president, Sooronobay Jeenbekov, resigned from his position and his duties were taken over by the opposition leader, Sadyr Japarov. The change in power was brought about by large-scale protests which broke out on 5 October, the day after the election; subsequently the protesters took over the main buildings of the central administration in Bishkek and released op- position leaders who had been imprisoned (among them Japarov). The demonstrations, which were forceful but not long-lasting, resulted in a compromise of sorts which led to changes in the highest state positions, the announcement of an early presidential election and a rerun of the parliamentary election. Despite the situation in the country (particularly in the capital) having been restored to one of relative stability, Kyrgyzstan is still struggling with grave problems: a crisis of the political system, social tensions and a dismal economic situation that is further exacerbated by the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. The current state of affairs presents a serious challenge both for Russia and China, whose respective interests have an important impact on the politics of Kyrgyzstan and the entire region of Central Asia. The October Revolution accusations of being implicated in organised crime. Traditionally, the main political forces try to play The Revolution of 5 October is the third such event off the international actors present in Kyrgyzstan in Kyrgyzstan’s recent history (the previous ones (Russia and China which replaced the US at least took place in 2005 and 2010). -

Redalyc.Drugs, Violence, and State-Sponsored Protection

Colombia Internacional ISSN: 0121-5612 [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia Snyder, Richard; Durán Martínez, Angélica Drugs, Violence, and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets in Mexico and Colombia Colombia Internacional, núm. 70, julio-diciembre, 2009, pp. 61-91 Universidad de Los Andes Bogotá, D.C., Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81215371004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Colombia Internacional 70, julio a diciembre de 2009: 61-91 Drugs, Violence, and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets in Mexico and Colombia Richard Snyder • Angélica Durán Martínez Brown University Abstract Illegality does not necessarily breed violence. The relationship between illicit markets and violence depends on institutions of protection. When state-sponsored protection rackets form, illicit markets can be peaceful. Conversely, the breakdown of state-sponsored protection rackets, which may result from well-meaning policy reforms intended to reduce corruption and improve law enforcement, can lead to violence. The cases of drug trafficking in contemporary Mexico and Colombia show how a focus on the emergence and breakdown of state-sponsored protection rackets helps explain variation in levels of violence both within and across illicit markets. Keywords protection rackets • drugs • violence • Mexico • Colombia Drogas, violencia y redes extorsivas con apoyo del Estado en México y Colombia Resumen La ilegalidad no necesariamente engendra violencia. La relación entre mercados ilícitos y violencia depende de la existencia de instituciones de protección. -

Here a Causal Relationship? Contemporary Economics, 9(1), 45–60

Bibliography on Corruption and Anticorruption Professor Matthew C. Stephenson Harvard Law School http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/mstephenson/ March 2021 Aaken, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Do individual disclosure rules for parliamentarians improve government effectiveness? Economics of Governance, 12(4), 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-011-0100-8 Aaronson, S. A. (2011a). Does the WTO Help Member States Clean Up? Available at SSRN 1922190. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1922190 Aaronson, S. A. (2011b). Limited partnership: Business, government, civil society, and the public in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Public Administration and Development, 31(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.588 Aaronson, S. A., & Abouharb, M. R. (2014). Corruption, Conflicts of Interest and the WTO. In J.-B. Auby, E. Breen, & T. Perroud (Eds.), Corruption and conflicts of interest: A comparative law approach (pp. 183–197). Edward Elgar PubLtd. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebookbatch.GEN_batch:ELGAR01620140507 Abbas Drebee, H., & Azam Abdul-Razak, N. (2020). The Impact of Corruption on Agriculture Sector in Iraq: Econometrics Approach. IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science, 553(1), 12019-. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/553/1/012019 Abbink, K., Dasgupta, U., Gangadharan, L., & Jain, T. (2014). Letting the briber go free: An experiment on mitigating harassment bribes. JOURNAL OF PUBLIC ECONOMICS, 111(Journal Article), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.12.012 Abbink, Klaus. (2004). Staff rotation as an anti-corruption policy: An experimental study. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(4), 887–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2003.10.008 Abbink, Klaus. -

Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: Coalition Situations and Government Transitions

SIGMA Papers No. 22 Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: OECD Coalition Situations and Government Transitions https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kml614vl4wh-en Unclassified CCET/SIGMA/PUMA(98)1 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques OLIS : 10-Feb-1998 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Dist. : 11-Feb-1998 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Or. Eng. SUPPORT FOR IMPROVEMENT IN GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (SIGMA) A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE OECD/CCET AND EC/PHARE Unclassified CCET/SIGMA/PUMA Cancels & replaces the same document: distributed 26-Jan-1998 ( 98 ) 1 MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES AT THE CENTRE OF GOVERNMENT: COALITION SITUATIONS AND GOVERNMENT TRANSITIONS SIGMA PAPERS: No. 22 Or. En 61747 g . Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format CCET/SIGMA/PUMA(98)1 THE SIGMA PROGRAMME SIGMA — Support for Improvement in Governance and Management in Central and Eastern European Countries — is a joint initiative of the OECD Centre for Co-operation with the Economies in Transition and the European Union’s Phare Programme. The initiative supports public administration reform efforts in thirteen countries in transition, and is financed mostly by Phare. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is an intergovernmental organisation of 29 democracies with advanced market economies. The Centre channels the Organisation’s advice and assistance over a wide range of economic issues to reforming countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Phare provides grant financing to support its partner countries in Central and Eastern Europe to the stage where they are ready to assume the obligations of membership of the European Union. -

Direct Democracy an Overview of the International IDEA Handbook © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008

Direct Democracy An Overview of the International IDEA Handbook © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008 International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The map presented in this publication does not imply on the part of the Institute any judgement on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement of such boundaries, nor does the placement or size of any country or territory reflect the political view of the Institute. The map is created for this publication in order to add clarity to the text. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: International IDEA SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications. Cover design by: Helena Lunding Map design: Kristina Schollin-Borg Graphic design by: Bulls Graphics AB Printed by: Bulls Graphics AB ISBN: 978-91-85724-54-3 Contents 1. Introduction: the instruments of direct democracy 4 2. When the authorities call a referendum 5 Procedural aspects 9 Timing 10 The ballot text 11 The campaign: organization and regulation 11 Voting qualifications, mechanisms and rules 12 Conclusions 13 3. When citizens take the initiative: design and political considerations 14 Design aspects 15 Restrictions and procedures 16 Conclusions 18 4. Agenda initiatives: when citizens can get a proposal on the legislative agenda 19 Conclusions 21 5. -

FCPA & Anti-Bribery

alertFall 2019 FCPA & Anti-Bribery Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP A New York Limited Liability Partnership • One Battery Park Plaza New York, New York 10004-1482 • +1 (212) 837-6000 Attorney advertising. Readers are advised that prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. No aspect of this advertisement has been approved by the Supreme Court of New Jersey. © 2019 Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP CORRUPTION PERCEPTION SCORE No Data 100 Very Clean 50 0 Very Corrupt Data from Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2018. SCORE COUNTRY/TERRITORY RANK 67 Chile 27 52 Grenada 53 41 India 78 35 Armenia 105 29 Honduras 132 23 Uzbekistan 158 88 Denmark 1 66 Seychelles 28 52 Italy 53 41 Kuwait 78 35 Brazil 105 29 Kyrgyzstan 132 22 Zimbabwe 160 87 New Zealand 2 65 Bahamas 29 52 Oman 53 41 Lesotho 78 35 Côte d’Ivoire 105 29 Laos 132 20 Cambodia 161 85 Finland 3 64 Portugal 30 51 Mauritius 56 41 Trinidad 78 35 Egypt 105 29 Myanmar 132 20 Democratic 161 85 Singapore 3 63 Brunei 31 50 Slovakia 57 and Tobago 35 El Salvador 105 29 Paraguay 132 Republic of the Congo 85 Sweden 3 Darussalam 49 Jordan 58 41 Turkey 78 35 Peru 105 28 Guinea 138 20 Haiti 161 85 Switzerland 3 63 Taiwan 31 49 Saudi Arabia 58 40 Argentina 85 35 Timor-Leste 105 28 Iran 138 20 Turkmenistan 161 84 Norway 7 62 Qatar 33 48 Croatia 60 40 Benin 85 35 Zambia 105 28 Lebanon 138 19 Angola 165 82 Netherlands 8 61 Botswana 34 47 Cuba 61 39 China 87 34 Ecuador 114 28 Mexico 138 19 Chad 165 81 Canada 9 61 Israel 34 47 Malaysia 61 39 Serbia 87 34 Ethiopia 114 28 Papua 138 19 Congo 165 -

The E-Parliament Election Index: A

The e-Parliament Election Index A global survey on the quality of practices in parliamentary elections by Professor M. Steven Fish University of California-Berkeley EMBARGOED: 12 noon GMT May 8th 2009 1 pm British Summer Time 2 pm South African Time 2 pm Central European Time 5.30 pm Indian Time 8 am New York Time 5 am California Time FOR MORE INFORMATION: Please contact Jasper Bouverie on +44-1233-812037 or [email protected] e-Parliament Election Index 2008-09 0-5 = closed or no electoral process 6-8 = restrictive electoral process 9-10 = mostly open electoral process 11-12 = open electoral process This data was collected by Professor Steve Fish of Berkeley University in California. Only countries with populations of over 250,000 were evaluated Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Country Ratings 19 e-Parliament Election Index 59 Expert Consultants 64 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the modern world, national legislatures are the primary nexus between the government and the governed. In some polities, they are what Max Weber said they should be: the “proper palaestra” of political struggle. In such places, the link between state and society is often robust. In other countries the legislature is a mere decoration, rendering the link between rulers and the ruled tenuous or nonexistent. Where parliaments are strong, there is at least some prospect for popular control over the rulers. Where they are weak, there is a high probability that relations between rulers and the ruled will take the form of domination rather than governance. Where legislatures are strong, elections for them are momentous events. -

Drugs, Violence, and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets in Mexico and Colombia Richard Snyder • Angélica Durán Martínez Brown University

Colombia Internacional 70, julio a diciembre de 2009: 61-91 Drugs, Violence, and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets in Mexico and Colombia Richard Snyder • Angélica Durán Martínez Brown University Abstract Illegality does not necessarily breed violence. The relationship between illicit markets and violence depends on institutions of protection. When state-sponsored protection rackets form, illicit markets can be peaceful. Conversely, the breakdown of state-sponsored protection rackets, which may result from well-meaning policy reforms intended to reduce corruption and improve law enforcement, can lead to violence. The cases of drug trafficking in contemporary Mexico and Colombia show how a focus on the emergence and breakdown of state-sponsored protection rackets helps explain variation in levels of violence both within and across illicit markets. Keywords protection rackets • drugs • violence • Mexico • Colombia Drogas, violencia y redes extorsivas con apoyo del Estado en México y Colombia Resumen La ilegalidad no necesariamente engendra violencia. La relación entre mercados ilícitos y violencia depende de la existencia de instituciones de protección. Cuando se forman redes extorsivas con apoyo estatal, los mercados ilícitos pueden ser pacíficos. En cambio, el desplome de estas redes —que puede ser resultado de reformas políticas bienintencionadas planeadas para reducir los niveles de corrupción y para mejorar el cumplimiento de la ley— puede generar violencia. Las dinámicas recientes de trafico de drogas en México y Colombia muestran que un enfoque en la aparición y desplome de redes extorsivas con apoyo estatal ayuda a explicar las variaciones en los niveles de violencia que existen dentro y a través de los mercados ilícitos. Palabras clave: redes extorsivas • drogas • violencia • México • Colombia Recibido el 4 de mayo de 2009 y aceptado el 20 de octubre de 2009.