The Catalog 2008-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Optical Satellite Communication Toward the Future of Ultra High

No.466 OCT 2017 Optical Satellite Communication toward the Future of Ultra High-speed Wireless Communications No.466 OCT 2017 National Institute of Information and Communications Technology CONTENTS FEATURE Optical Satellite Communication toward the Future of Ultra High-speed Wireless Communications 1 INTERVIEW New Possibilities Demonstrated by Micro-satellites Morio TOYOSHIMA 4 A Deep-space Optical Communication and Ranging Application Single photon detector and receiver for observation of space debris Hiroo KUNIMORI 6 Environmental-data Collection System for Satellite-to-Ground Optical Communications Verification of the site diversity effect Kenji SUZUKI 8 Optical Observation System for Satellites Using Optical Telescopes Supporting safe satellite operation and satellite communication experiment Tetsuharu FUSE 10 Development of "HICALI" Ultra-high-speed optical satellite communication between a geosynchronous satellite and the ground Toshihiro KUBO-OKA TOPICS 12 NICT Intellectual Property -Series 6- Live Electrooptic Imaging (LEI) Camera —Real-time visual comprehension of invisible electromagnetic waves— 13 Awards 13 Development of the “STARDUST” Cyber-attack Enticement Platform Cover photo Optical telescope with 1 m primary mirror. It receives data by collecting light from sat- ellites. This was the main telescope used in experiments with the Small Optical TrAn- sponder (SOTA). This optical telescope has three focal planes, a Cassegrain, a Nasmyth, and a coudé. The photo in the upper left of this page shows SOTA mounted in a 50 kg-class micro- satellite. In a world-leading effort, this was developed to conduct basic research on technology for 1.5-micron band optical communication between low-earth-orbit sat- ellite and the ground and to test satellite-mounted equipment in a space environment. -

The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius

,.J: - f^^^- \ ^ xxV^Jr^^ EEx Libris K. OGDEN Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/atticniglitsofaul02gelliala THE ATTIC NIGHTS O P AULUS GELLIUS TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH, By THE Rev. W. B E L O E, f. s. a. XRANSLAro R OF HERODOTUS, &C. IN THREE VOLUMES. V O L. U. LONDON: I'RINTKn FO. ;. ;0HN50N. ST. p.ul's CHU^CH-VA.o. M Dec XCV. Annex PR £5-. THE ATTIC NIGHTS O F AULUS GELLIUS. BOOK VL Chap, I. The reply of Chryjippus to thoje who denied a Pro* vidence. ' ^r'HE Y who think that the world was not pro- duced on account of the Deity and of man, and deny that human affairs are governed by Providence, think * The beginning of this chapter was wanting in all the editions with which I am acquainted ; but I have reftored it from Laftantius's Epitome of his Divine Inftitutions, Chap. 29. It is a whimfical circumftance enough, that the greater part of this very Epitome ftiould have lain hid till the pre- fent century. St. Jerome, in his Catalogue of Ecclefiailical Writers, fpeaking of Laflaatius, fays, " Habemus ejus In- ftitiitionum Divinarum adverfus gentes libros feptem eitEpi- VOL. II, B tome ; « THE ATTIC NIGHTS think that they urge a 'powerful argument when they offerti that if there were a Providence there would he no evils. For nothings they affirm., can be lefs conftfi^ ent with a Providence, than that in that world, oH account of which the Deity is /aid to have created man, there fhould exijl fo great a number of cala- mities and evils. -

The Southern Ocean Clouds,Radiation, Aerosol Transport Experimental Study

THE SOUTHERN OCEAN CLOUDS, RADIATION, AEROSOL TRANSPORT EXPERIMENTAL STUDY THE SOCRATES PLANNING TEAM Roj Marchand, Robert Wood, Chris Bretherton, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington Greg McFarquhar, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois Alain Protat, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia Patricia Quinn, NOAA PMEL, Seattle Steven Siems and Christian Jakob, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Simon Alexander, Australian Antarctic Division, Kingston, Tasmania, Australia Bob Weller, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Woods Hole, Massachusetts SOCRATES WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS AND CONTRIBUTORS Steve Ghan, Chris Hostetler, Gijs de Boer, Jay Mace, Pavlos Kollias, Richard Moore, Theodore Wilson, Dennis Hartmann, Jorgen Jensen, Jennifer Kay, Lynn Russell, Jacob Scheff, Elizabeth Maroon, Susannah Burrows, Sara Tucker, Jeff Stith, James Hudson, Joellen Russell, Yan Feng, Paul DeMott, Tom Lachlan‐Cope, Paulo Ceppi, Daniel Grosvenor, Daniel McCoy, Nicholas Meskhidze, Chris Fairall, Sarah Gille, Tim Bates, Cassandra Gaston, Erica Dolinar, Ryan Stanfield, Keith Williams, Alejandro Bodas‐Salcedo, Bob Rauber, Mike Harvey, Antony Clarke, Monica Orellana, Andreas Muhlbauer, Lorenzo Polvani, Yongxiang Hu, Scott Collis, Anna Gannet Hallar, Ying Li, Adrian James McDonald, Kalli Furtado, Gregory Roberts, Ann Fridlind, Andrew Ackerman, Carol Clayson, Benjamin Hillman 1 Preamble The Southern Ocean (SO) is the stormiest place on earth, buffeted by winds and waves that circle the ice of Antarctica, sheathed in clouds that mantle a dynamic ocean with rich ecosystems, and remote from most human influences. It influences the atmospheric and oceanic circulation of the entire southern hemisphere and beyond. The remoteness from anthropogenic and natural continental aerosol sources makes the SO a unique testbed for our understanding of cloud‐aerosol interaction, both for liquid and ice clouds, and the role of marine biogenic aerosols and their precursors. -

H-2 Family Home Launch Vehicles Japan

Please make a donation to support Gunter's Space Page. Thank you very much for visiting Gunter's Space Page. I hope that this site is useful a nd informative for you. If you appreciate the information provided on this site, please consider supporting my work by making a simp le and secure donation via PayPal. Please help to run the website and keep everything free of charge. Thank you very much. H-2 Family Home Launch Vehicles Japan H-2 (ETS 6) [NASDA] H-2 with SSB (SFU / GMS 5) [NASDA] H-2S (MTSat 1) [NASDA] H-2A-202 (GPM) [JAXA] 4S fairing H-2A-2022 (SELENE) [JAXA] H-2A-2024 (MDS 1 / VEP 3) [NASDA] H-2A-204 (ETS 8) [JAXA] H-2B (HTV 3) [JAXA] Version Strap-On Stage 1 Stage 2 H-2 (2 × SRB) 2 × SRB LE-7 LE-5A H-2 (2 × SRB, 2 × SSB) 2 × SRB LE-7 LE-5A 2 × SSB H-2S (2 × SRB) 2 × SRB LE-7 LE-5B H-2A-1024 * 2 × SRB-A LE-7A - 4 × Castor-4AXL H-2A-202 2 × SRB-A LE-7A LE-5B H-2A-2022 2 × SRB-A LE-7A LE-5B 2 × Castor-4AXL H-2A-2024 2 × SRB-A LE-7A LE-5B 4 × Castor-4AXL H-2A-204 4 × SRB-A LE-7A LE-5B H-2A-212 ** 1 LRB / 2 LE-7A LE-7A LE-5B 2 × SRB-A H-2A-222 ** 2 LRB / 2 × 2 LE-7A LE-7A LE-5B 2 × SRB-A H-2A-204A ** 4 × SRB-A LE-7A Widebody / LE-5B H-2A-222A ** 2 LRB / 2 × LE-7A LE-7A Widebody / LE-5B 2 × SRB-A H-2B-304 4 × SRB-A Widebody / 2 LE-7A LE-5B H-2B-304A ** 4 × SRB-A Widebody / 2 LE-7A Widebody / LE-5B * = suborbital ** = under stud y Performance (kg) LEO LPEO SSO GTO GEO MolO IP H-2 (2 × SRB) 3800 H-2 (2 × SRB, 2 × SSB) 3930 H-2S (2 × SRB) 4000 H-2A-1024 - - - - - - - H-2A-202 10000 4100 H-2A-2022 4500 H-2A-2024 5000 H-2A-204 6000 H-2A-212 -

On the Daimonion of Socrates

SAPERE Scripta Antiquitatis Posterioris ad Ethicam REligionemque pertinentia Schriften der späteren Antike zu ethischen und religiösen Fragen Herausgegeben von Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Reinhard Feldmeier und Rainer Hirsch-Luipold Band XVI Plutarch On the daimonion of Socrates Human liberation, divine guidance and philosophy edited by Heinz-Günther Nesselrath Introduction, Text, Translation and Interpretative Essays by Donald Russell, George Cawkwell, Werner Deuse, John Dillon, Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Robert Parker, Christopher Pelling, Stephan Schröder Mohr Siebeck e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-156444-4 ISBN 978-3-16-150138-8 (cloth) ISBN 987-3-16-150137-1 (paperback) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nal bibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is availableon the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de. © 2010 by Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. This book was typeset by Christoph Alexander Martsch, Serena Pirrotta and Thorsten Stolper at the SAPERE Research Institute, Göttingen, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. SAPERE Greek and Latin texts of Later Antiquity (1st–4th centuries AD) have for a long time been overshadowed by those dating back to so-called ‘classi- cal’ times. The first four centuries of our era have, however, produced a cornucopia of works in Greek and Latin dealing with questions of philoso- phy, ethics, and religion that continue to be relevant even today. -

Space Security 2010

SPACE SECURITY 2010 spacesecurity.org SPACE 2010SECURITY SPACESECURITY.ORG iii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data Space Security 2010 ISBN : 978-1-895722-78-9 © 2010 SPACESECURITY.ORG Edited by Cesar Jaramillo Design and layout: Creative Services, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Cover image: Artist rendition of the February 2009 satellite collision between Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33. Artwork courtesy of Phil Smith. Printed in Canada Printer: Pandora Press, Kitchener, Ontario First published August 2010 Please direct inquires to: Cesar Jaramillo Project Ploughshares 57 Erb Street West Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541, ext. 708 Fax: 519-888-0018 Email: [email protected] iv Governance Group Cesar Jaramillo Managing Editor, Project Ploughshares Phillip Baines Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Canada Dr. Ram Jakhu Institute of Air and Space Law, McGill University John Siebert Project Ploughshares Dr. Jennifer Simons The Simons Foundation Dr. Ray Williamson Secure World Foundation Advisory Board Hon. Philip E. Coyle III Center for Defense Information Richard DalBello Intelsat General Corporation Theresa Hitchens United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Dr. John Logsdon The George Washington University (Prof. emeritus) Dr. Lucy Stojak HEC Montréal/International Space University v Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 Acronyms PAGE 7 Introduction PAGE 11 Acknowledgements PAGE 13 Executive Summary PAGE 29 Chapter 1 – The Space Environment: -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17292-9 - Precipitation: Theory, Measurement and Distribution Ian Strangeways Index More information Index adiabatic lapse rate 68 Castelli, Benedetto – raingauge experiment 143 aerodynamic raingauges 167 Charles’s law 31, 40 air pump 28, 34 chemistry in evaporation 30 Airy, George – cloud droplets 36 China (ancient) 3 Aitkin, John – cloud nuclei experiments 42 church, power of 13 Alter, J. C. – wind shield for raingauge 165 cirrocumulus clouds 94 altocumulus clouds 87 cirrostratus clouds 94 altostratus clouds 95 cirrus clouds 91 Amontons, Guillaume – barometric pressure 30 Climatic Research Unit datasets 233 Anaxagoras – rivers, rain, Homeric ocean, hail 5, 7, 9 cloud chamber 34, 35, 36 Anaximander – wind is moving air 5 cloud physics 46, 70 Antarctic Oscillation and effect on precipitation 271 clouds Arctic Oscillation and effect on precipitation 270 classification and identification 70–3 areal estimates of precipitation from point droplet formation 106–8 measurements 237–42 early ideas 33–43 Aristophanes – The Clouds 6 formation 75–7 Aristotle measurement of base height 101–4 decline of his teachings 13 observation from satellites 73 on dew 48 coalescence in raindrop formation 44, 108 on rain 9 compression theory in raindrop formation 43 return of his teachings 17 condensation views on the elements and rain 7–10 see especially 39, 41, 44–52, 68 atmosphere convection see especially 29–30, 60, 63 forced, mixed, free – dispersion of water vapour by 65 Bacon, Francis – the scientific method 21 role in cloud formation 38 ball lightning 123 cooling balloon flights – investigating atmospheric by infrared radiation 50 composition 32 by rarefaction, expansion, ascent 39–41 Barlow, Edward – raindrops by compression 44 Coulier, P. -

Description of SOCRATES-A Chemical Dynamical Radiative Two

NCAR/TN-440+EDD NCAR TECHNICAL NOTE March 1998 Description of SOCRATES- A Chemical Dynamical Radiative Two-Dimensional Model Theresa Huang Stacy Walters Guy Brasseur Didier Hauglustaine Wanli Wu Simon Chabrillat Xuexi Tie Claire Granier Anne Smith Sasha Madronich Gaston Kockarts ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY DIVISION - ii i: I I NATIONAL CENTER FOR ATMOSPHERIC RESEARCH BOULDER, COLORADO *ii Table of Contents L ist o f T ables ....................................................................................... v L ist of F igures..........................................................................ii 1. Overview .......... ................................... ..................... 2. Model Physics and Chemistry .............................................................. 5 3. Radiation .................................................................... .7 3.1 Ultraviolet (UV) and visible radiative region (117 - 730 nm)...................7 3.2 Infrared (IR) radiative regime (A > 3 pn )........................................ 19 4. D ynam ics .................... .. .... .................................. 23 4.1 Planetary waves......................................................................23 4.2 Gravity waves ........................................................... 26 4.4. Tropospheric wave forcing and latent heating specification....................29 4.5 The circulation global mass balance correction .................................... 30 4.6 Molecular diffusivity parameterization......................................... 31 -

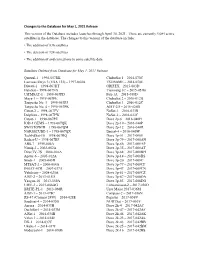

Changes to the Database for May 1, 2021 Release This Version of the Database Includes Launches Through April 30, 2021

Changes to the Database for May 1, 2021 Release This version of the Database includes launches through April 30, 2021. There are currently 4,084 active satellites in the database. The changes to this version of the database include: • The addition of 836 satellites • The deletion of 124 satellites • The addition of and corrections to some satellite data Satellites Deleted from Database for May 1, 2021 Release Quetzal-1 – 1998-057RK ChubuSat 1 – 2014-070C Lacrosse/Onyx 3 (USA 133) – 1997-064A TSUBAME – 2014-070E Diwata-1 – 1998-067HT GRIFEX – 2015-003D HaloSat – 1998-067NX Tianwang 1C – 2015-051B UiTMSAT-1 – 1998-067PD Fox-1A – 2015-058D Maya-1 -- 1998-067PE ChubuSat 2 – 2016-012B Tanyusha No. 3 – 1998-067PJ ChubuSat 3 – 2016-012C Tanyusha No. 4 – 1998-067PK AIST-2D – 2016-026B Catsat-2 -- 1998-067PV ÑuSat-1 – 2016-033B Delphini – 1998-067PW ÑuSat-2 – 2016-033C Catsat-1 – 1998-067PZ Dove 2p-6 – 2016-040H IOD-1 GEMS – 1998-067QK Dove 2p-10 – 2016-040P SWIATOWID – 1998-067QM Dove 2p-12 – 2016-040R NARSSCUBE-1 – 1998-067QX Beesat-4 – 2016-040W TechEdSat-10 – 1998-067RQ Dove 3p-51 – 2017-008E Radsat-U – 1998-067RF Dove 3p-79 – 2017-008AN ABS-7 – 1999-046A Dove 3p-86 – 2017-008AP Nimiq-2 – 2002-062A Dove 3p-35 – 2017-008AT DirecTV-7S – 2004-016A Dove 3p-68 – 2017-008BH Apstar-6 – 2005-012A Dove 3p-14 – 2017-008BS Sinah-1 – 2005-043D Dove 3p-20 – 2017-008C MTSAT-2 – 2006-004A Dove 3p-77 – 2017-008CF INSAT-4CR – 2007-037A Dove 3p-47 – 2017-008CN Yubileiny – 2008-025A Dove 3p-81 – 2017-008CZ AIST-2 – 2013-015D Dove 3p-87 – 2017-008DA Yaogan-18 -

Espinsights the Global Space Activity Monitor

ESPInsights The Global Space Activity Monitor Issue 4 October-December 2019 CONTENTS FOCUS ..................................................................................................................... 6 ESA Ministerial Council Space19+ concludes with biggest ever financial contribution ...................... 6 SPACE POLICY AND PROGRAMMES .................................................................................... 7 EUROPE ................................................................................................................. 7 European GSA and World Geospatial Industry Council sign agreement ..................................... 7 Ariane 6 on track for first launch in 2020 ....................................................................... 7 World’s first space debris removal mission commissioned by ESA ........................................... 7 ESA signs contract for new version of EGNOS system .......................................................... 7 Initial tests completed for Europe’s next generation weather forecasting system ....................... 8 ESA and Luxembourg Space Agency sign Memorandum of Cooperation ..................................... 8 CNES signs agreement with ESA on interoperability of mission control centres ........................... 8 Declaration of Intent signed between France and USA on SSA and STM .................................... 8 Construction of Scottish Spaceport reported to begin within next year .................................... 8 German Aerospace Centre signs -

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd

UNISEC Global Meeting Tokyo, July 2015 (Pre-workshop for the 4 th Mission Idea Contest for Micro / Nano Satellite Utilisation) SSTL Overview • UK small satellite mission provider • - owned by 99% Airbus Defence & Space 1% University of Surrey • Incorporated in 1985, employs 500 staff across facilities in the UK (Surrey, Kent, Hampshire) & US (Colorado) SSTL – The Stats 34+ 43 21 Years+ in operation. SSTL Satellites in manufacture 6 Oct 1981 to date. satellites launched 5 22 Number of SSTL constellations deployed and under contract Payloads in manufacture (DMC, RapidEye, F7, DMC3, Kanopus) Changing the Economics of Space As at July 2014 SSTL’s fleet of small satellites Cubesats SSTL-X50 SSTL NovaSAR SSTL 100 SSTL 150 SSTL 300 SSTL 300 S1 SSTL GMP-T Japanese Collaborators SSTJ – Resource Provider into MIC Leverage SSTL’s expertise to assist MIC participants through: 1. Mentoring – providing technical advice 2. Work-shop participation 3. Training & Development 4. Provision of heritage platforms and subsystems SSTL Available Resources Full mission capability from definition through to launch, commission, operations & exploitation Mission Definition and Design Sub Systems Design and Manufacturing Assembly & Integration Testing Environmental Testing Launch Mission Commission & Operations Image Processing & Application SSTL collaborations with Japan Space Industry include: 1. Mission Concept Studies 2. Microsatellite Mission Training 3. Space Market Study & Analysis 4. Technical (spacecraft, platform & equipment) Studies 5. Subsystem provision (EM & FM) 5. Ground Station Provision / Training 6. Down stream data service provision Japanese Missions Supported by SSTL SLATS JAXA / MELCO SLATS – SSTL provided Study support and is supplying GPS space receiver SOCRATES NICT SOCRATES – AES ChubuSat ChubuSat – MHI / prime.