Tensile Properties of Thermoplastic Starch and Its Blends with Polyvinyl Butyral and Polyamides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Types of Noncrystalline Polymers

2 Types of Noncrystalline Polymers 1. Glassy polymer highly interpenetrated/entangled 2. Rubbery polymers random Gaussian coils Glass Transition Temperature εij Two viewpoints: • Increasing T: When kT > magnitude of εij, the thermal fluctuations can overcome local intermolecular bonds and the frozen (“glassy”) structure becomes “fluid-like”. • Decreasing T: As the temperature is lowered and T approaches Tg, the viscosity increases to ∞ and the material becomes “solid” Free Volume Theory of Tg Free volume, VF – extra space beyond what is present in an ordered crystalline packing (beyond the interstitial volume). VF(T) ≡ V(T) – V0(T) • V0 is occupied specific volume of atoms or molecules in the xline state and the spaces between them: ~ VXL. V(T) α • VF increases as T increases due to the Rate of cooling l difference in the thermal expansion V (T) αg XL coefficients (αg vs αl). FAST SLOW • V0(T) ≈ VXL(T) ↔ can take αg ≈αXL dV •V(T) = V (T ) + (T-T ) F T > T F F g g dT g Tg T • define fractional free volume, fF:Vf/V fF(T) = fF(Tg) + (T-Tg)αf αf = αl – αg Viewpoint: Tg occurs when available free volume drops below critical threshold for structural rearrangement [VITRIFICATION POINT], structure “jams up”. Tg Values of Amorphous Materials Table of representative amorphous solids, their bonding types, and their glass transition temperatures removed due to copyright restrictions. See Table 2.2 in Allen, S. M., and E.L. Thomas. The Structure of Materials. New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons, 1999. Tg for Selected Polymers Glass Transition Temperature -

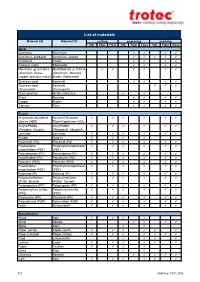

List of Materials

List of materials Material EN Material DE cutting engraving marking CO2 Fiber Flexx CO2 Fiber Flexx CO2 Fiber Flexx Metal Aluminum Aluminium Aluminum, anodized Aluminium, eloxiert Chromium Chrom Precious metal Edelmetall Metal foils up to 0.5mm Metallfolie bis zu 0,5mm (Aluminum, Brass, (Aluminium, Messing, Copper, precious metal) Kupfer, Edelmetall) Stainless steel Edelstahl Stainless steel Edelstahl (Thermark®) (Thermark®) Metal, painted Metall, lackiertes Brass Messing Copper Kupfer Titanium Titan Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene Acrylnitril-Butadien- styrene (ABS) Styrol-Copolymer (ABS) Acrylic/PMMA Acryl/PMMA (Plexiglas, Altuglas, (Plexiglas®, Altuglas®, LaminatePerspex) LaminatePerspex®) Rubber Gummi Polyamide (PA) Polyamid (PA) Polybutylene Polybutylenterephthalat terephthalate (PBT) (PBT) Polycarbonate (PC) Polycarbonat (PC) Polyethylene (PE) Polyethylen (PE) Polyester (PES) Polyester (PES) Polyethylene Polyethylenterephthalat terephthalate (PET) (PET) Polyimide (PI) Polyimid (PI) Polyoxymethylene Polyoxymethylen (POM) -Delrin® (POM) - Delrin® Polypropylene (PP) Polypropylen (PP) Polyphenylene sulfide Polyphenylensulfid (PPS) (PPS) Polystyrene (PS) Polystyrol (PS) Polyurethane (PUR) Polyurethan (PUR) Foam Schaumstoff Miscellanious Wood Holz Mirror Spiegel Stone Stein Paper (white) Papier (weiß) Paper (colored) Papier (färbig) Food Lebensmittel Leather Leder -

Use of a Crosslinking Agent, Crosslinked Polymer, and Uses Thereof

(19) TZZ Z_T (11) EP 2 452 970 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C08K 5/09 (2006.01) B32B 27/30 (2006.01) 21.01.2015 Bulletin 2015/04 C08L 29/04 (2006.01) C08L 101/00 (2006.01) G02B 5/30 (2006.01) C08K 5/098 (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 12154871.3 C08K 5/10 (22) Date of filing: 29.08.2008 (54) Use of a crosslinking agent, crosslinked polymer, and uses thereof Verwendung eines Vernetzungsmittels, vernetztes Polymer und Verwendungen davon Utilisation d’un agent de réticulation, polymère réticulé et utilisations associées (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR • Kageyama, Hideki HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL NO PL PT Osaka-shi, Osaka 530-0018 (JP) RO SE SI SK TR • Tanaka, Shinichi Osaka-shi, Osaka 530-0018 (JP) (30) Priority: 31.08.2007 JP 2007225012 • Ono, Hiroyuki 18.03.2008 JP 2008069645 Osaka-shi, Osaka 530-0018 (JP) 04.04.2008 JP 2008098282 • Kuruma, Akiko 11.04.2008 JP 2008103494 Osaka-shi, Osaka 530-0018 (JP) 24.04.2008 JP 2008114149 24.04.2008 JP 2008114150 (74) Representative: Kuhnen & Wacker Patent- und Rechtsanwaltsbüro (43) Date of publication of application: Prinz-Ludwig-Straße 40A 16.05.2012 Bulletin 2012/20 85354 Freising (DE) (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in (56) References cited: accordance with Art. 76 EPC: WO-A1-2005/087711 JP-B2- 3 612 124 08828502.8 / 2 189 496 US-A1- 2004 102 586 (73) Proprietor: The Nippon Synthetic Chemical • DATABASE WPI Week 198020 Thomson Industry Co., Ltd. -

BASEL CONVENTION PLASTICS AMENDMENTS Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI)

BASEL CONVENTION PLASTICS AMENDMENTS Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) Adina Renee Adler Assistant Vice President, International Affairs ©2019 Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved The Driver 2 Basel Convention Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal Adopted 22 March 1989 Entered into force on 5 May 1992 Currently has 187 parties The United States is not a party. OCTOBER 2019 | ISRI.ORG 3 ©2019 ISRI, Inc. Basel Convention Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal Subjects hazardous wastes or other wastes with hazardous constituents / exhibiting hazardous characteristics to a “prior informed consent” (PIC) procedure before the material can be shipped across national borders. The PIC gives the receiving country the right of refusal if proper recycling or disposal operations do not exist. OCTOBER 2019 | ISRI.ORG 4 ©2019 ISRI, Inc. Basel Convention 14th Conference of the Parties (COP) held every two years to direct work on implementing the convention and addressing emerging issues. OCTOBER 2019 | ISRI.ORG 5 ©2019 ISRI, Inc. Norway’s Proposal Amend the following annexes so that trade controls are 1 put into place for certain plastics: Annex II: Non-hazardous, hard-to-recycle plastics Annex VIII: Hazardous plastics Annex IX: Non-hazardous, easy-to-recycle plastics (exempt from BC) Create a Partnership for Plastic Waste that would involve public and private stakeholders to find possible solutions 2 to plastic leakage. Terms of Reference negotiated and adopted. It will lead to non- binding initiatives to support developing country improvements to minimization, collection and proper handling of end-of-life plastics. -

Polyvinylbutyral HVB-0001

Technical Information Polyvinylbutyral HVB-0001 Description: HVB-0001 is high viscosity thermoplastic Polyvinylbutyral Resin combining a very large surface area with medium molecular weight. Its sensorial properties are outstanding. The product is soluble in solvents like Alcohols or Glycol Ethers, it is compatible with Esters and Ketones. HVB-0001 shows excellent compatibility with other resins like Nitrocellulose, Epoxy Resins, Epoxy Alkyds, Phenolic Resins, Polyurethanes, Melamine-Formaldehyde Resins, Ketonic Resins and Polyamides. With its free hydroxyl groups the material is chemically reactive. Application: Printing Inks and lacquers: HVB-0001 is an ideal choice for formation of printing inks for flexible packaging (Flexographic & Gravure application). The product offers good water resistance combined with good blocking resistance, excellent pigment wetting and good flow. It shows good adhesion to substrates like Cellulose Acetate, Polyester, Polystyrene or Metalized Films. HVB-0001 is suitable for food packaging applications. Wash Primers: HVB-0001 can be used for formulation of wash primers for steel storage tanks, bottom of ships, airplane, bridges, dam locks, trailers, farm equipment, automotive, rail coaches etc. The material offers flexible films with good adhesion to metal surfaces. Adhesives: HVB-0001 acts as a plasticizer for adhesive formulations based on Epoxy, Phenolic, Melamine-Formaldehyde Resins and Isocyanates. It helps improving interfacial adhesion, flexibility, impact strength and resistance against solvent, chemicals or high temperature. Ceramics: HVB-0001 solution can be used as a temporary binder for ceramic powder. Typically 2 – 4 % PVB-resin are added to Ceramic. During sintering process HVB-0001 undergoes thermal degradation leaving virtually no residue. It leads to very good green strength and dimensional stability. -

Polyvinyl Butyral (PVB) PVB Thin Films Table of Contents

Polyvinyl butyral (PVB) PVB thin films Table of contents 1. Mowital® Thin Film 2. Advantages of Mowital® Thin Film 3. Key parameters of Mowital® Thin Film 4. Applications of Mowital® Thin Film January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 2 1. Mowital® Thin Film January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 3 1. Mowital® Thin Film Grade Thickness Width of Roll Length of Roll Mowital® Thin Film 050 50 µm 1 m 1500 m Mowital® Thin Film 075 75 µm 1 m 1500 m Mowital® Thin Film 100 100 µm 1 m 1500 m Mowital® Thin Film 250 250 µm 1 m 300 m § Application à Adhesive laminate film § Lamination of films components and fibre structures § Roll-to-roll lamination processes § Combination of different materials § Multilayer structures January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 4 2. Advantages of Mowital® Thin Film January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 5 2. Advantages of Mowital® Thin Film § Excellent adhesion to glass (glass fibres), metals, ceramics, wood and fabrics § Very good adhesion to most plastics § Thermoplastic material § Cross-linkable with epoxies, phenolics, isocyanates, etc. § High transparency § No migration of additives or plasticizers § Solvent- and dust free, no health and safety issues January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 6 3. Key parameters of Mowital® Thin Film January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 7 3. Key parameters of Mowital® Thin Film PVB Film Mowital® Thin Film Elastic modulus [N/mm2] ~ 100 2.300 - 2.400 Tensile strength [N/mm2] >23 45-60 Elongation [%] >280 4-7 Tg [°C] 18-20 70 Softening range [°C] 90-100 180-210 Refractive index 1.48 1.48 Surface resistivity [Ohm x m] 1011-1012 >1012 Volume resistivity [Ohm] 1011-1012 >1012 WVTR [g * 50 µm /(m2*d)] n/a 40-45 OTR [g * 50 µm /(m2*d)] n/a 680-700 Tg: Glass Transition Temperature; WVTR: Water vapour transmission rate; OTR: Oxygen transmission rate January 30, 2020 Global Business – Technical Resin 8 4. -

Polyvinyl Butyral Dispersions

(19) TZZ¥ Z_T (11) EP 3 269 760 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 17.01.2018 Bulletin 2018/03 C08J 5/18 (2006.01) C08K 3/26 (2006.01) C09D 129/14 (2006.01) C09D 131/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 16178902.9 C08K 5/098 C08K 5/10 C08K 13/02 (2006.01) C08L 29/14 (2006.01) (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 11.07.2016 C08L 31/04 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB • SMITH, Paul GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO Halifax, Yorkshire HX3 0QL (GB) PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR • BEWSHER, Alan Designated Extension States: Ripponden, Yorkshire HX6 4JE (GB) BA ME • RUGGLES, Colin Designated Validation States: Waltham Abbey, Essex EN9 3AW (GB) MA MD (74) Representative: Browne, Robin Forsythe et al (71) Applicant: Aquaspersions Ltd. Hepworth Browne Halifax, Yorkshire HX3 6AQ (GB) 15 St Paul’s Street Leeds LS1 2JG (GB) (54) POLYVINYL BUTYRAL DISPERSIONS (57) A stable aqueous film forming dispersion com- etate and mixtures thereof: prising: a plasticiser; a polymer selected from the group consisting of: polyvinyl an emulsifier; and butyral, polyvinyl acetyl, ethylene vinyl acetate, vinyl ac- a water soluble organometallic crosslinking agent. EP 3 269 760 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 3 269 760 A1 Description [0001] This invention relates to polymeric dispersions, particularly but not exclusively dispersions of polyvinyl butyral (PVB). -

Polyvinyl Butyral B-08HX Resin

distributed by: Request Quote or Samples Polyvinyl Butyral B-08HX CHANG CHUN GROUP Technical Data Sheet Effective date: 2015/08/10 Version : 1.0, Page 1/1 Characteristics CCP PVB B-08HX is a polyvinyl butyral resin with a medium solution viscosity. CCP PVB B-08HX is manufactured from the condensation reaction of Polyvinyl Alcohol and n-butyraldehyde. B-08HX is a thermoplastic resin, which is soluble in most organic solvents with excellent film forming capability, strong adhesion to glass, metal, plastic, leather and wood. CCP B-08HX is a white free flowing granule or powder and non-toxic to humans and animals. Specification Item value Unit Remark Butyral content 76 – 82 wt% Hydroxyl content 18.0 – 21.0 wt% Acetyl content ≦2 wt% Solution viscosity was determined in 10% by weight in Viscosity 120 – 180 cps ethanol/toluene = 1/1 at 20°C, using Brookfield viscometer Free Acid ≦0.05 wt% Volatile ≦3 wt% Application Additional Data Typical applications for B-08HX are - wash primer, Specific gravity : 1.05~1.10 paint, ceramic binder, coating and adhesive. Due to Bulk density : 0.25 – 0.40 g/cm³ for powder free hydroxyl groups, B08HX can be used as a Glass transition temperature : ca. 71 °C reactive component or as a co-binder in two-pack Melting Point : 135 – 185°C systems. For example, B08HX can be crosslinked Molecular weight : 52,000 – 62,000 g/mole with phenolic, epoxies, melamine, isocyanate resin. Degree of Polymerization : 800 - 900 Package CCP PVB B-08HX is packed in 10 kg, multi-ply paper bags. -

](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8107/mowital-technical-data-sheet-pdf-152kb-1308107.webp)

MOWITAL™ Technical Data Sheet [PDF](152KB)

Mowital Technical Data Sheet Characteristics Recommended Uses Form supplied Polyvinyl butyral (PVB) grades with Binder for coatings (adhesion promotion/ Fine-grained, free-flowing white powder. different molecular weights, and varying corrosion protection primers, shop degrees of acetalization. primers, wash primers, stoving enamels, varnishes and lacquers for different substrates). Binder for printing inks. Co- binder for powder coatings. Temporary binder for ceramics. Binder for textile printing and non-woven. Wetting agent for grindings, esp. of organic pigments. Adhesives, pressure-sensitive adhesives and hotmelts. Specification Data The data are determined by our quality control for each lot prior to release. 3) Grade Non-volatile Content of polyvinyl Content of polyvinyl Dynamic viscosity 1) 2) content alcohol acetate 10 % solution 4) (DIN 53216) in Ethanol wt-% wt-% wt-% mPa s Mowital B 14 S 97,5 14-18 5-8 9-13 Mowital B 16 H 97,5 18-21 1-4 14-20 Mowital B 20 H 97,5 18-21 1-4 20-30 Mowital B 30 T 97,5 24-27 1-4 30-55 Mowital B 30 H 97,5 18-21 1-4 35-60 Mowital B 30 HH 97,5 11-14 1-4 35-60 Mowital B 45 M 97,5 21-24 1-4 80-110 Mowital B 45 H 97,5 18-21 1-4 60-90 Mowital B 60 T 97,5 24-27 1-4 180-280 Mowital B 60 H 97,5 18-21 1-4 160-260 Mowital B 60 HH 97,5 12-16 1-4 120-280 Mowital B 75 H 97,5 18-21 0-4 60-100 5) 1) Hydroxyl groups in terms of polyvinyl alcohol 2) Acetyl groups in terms of polyvinyl acetate 3) according to DIN 53015, at 20 °C 4) containing 5 % water 5) viscosity of a 5 % solution August 2016 Additional Data Grade Glass transition Water up-take after 24 h Bulk density 1) temperature water immersion (DIN EN 543, (DSC, ISO 11357-1) at 20 °C Dec. -

Abbreviations for Various Plastic Materials Typical Molding Problems and Possible Causes

’TECHNICAL DATA» ’TECHNICAL DATA» ABBREVIATIONS FOR VARIOUS PLASTIC MATERIALS TYPICAL MOLDING PROBLEMS AND POSSIBLE CAUSES I List of Abbreviations for Plastic Materials In alphabetical order Cause Condition Molding machine Mold Material Abbreviations Resins (1 ) Low material temperature ( 1 ) Small gate or runner (1) Low fluidity ABS Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (2 ) Low injection pressure ( 2 ) Inadequate gate position (2) Low lubricity AS Styrene–acrylonitrile GSAN in ISO (3) Material feed shortage ( 3 ) Inadequate position of or no air vent CA Cellulose acetate Filling miss ( ) ( ) CAB Cellulose acetate butyrate 4 Too small nozzle hole diameter 4 Low mold temperature CF Cresol–formaldehyde (5 ) Cylinder nozzle clogging ( 5 ) Cold slag clogging in runner or gate CMC Carboxymethyl celluloss CN Cellulose nitrate CS Casein (1 ) Weak clamping force (1) Flaw or a foreign body on parting plane (1) Excessive fluidity EC Ethyl cellulose (2) High injection pressure (2) Wide project area to the machine Fin EP Epoxide; epoxy (3) Material overfeed (3) High mold temperature EVA Ethylene vinylalcohol (4) High material temperature LCP Liquid Crystal Polymer MF Melamine–formaldehyde (1) Low injection pressure (1) High mold temperature (1) Material, too supple PA Polyamide ( ) Slow injection ( ) ( ) G 2 2 Products thickness uneven 2 High contraction coefficient PBTP Poly butyrene terephthalate Also PBT Shrinkage (3) High material temperature (3) Small gate PC Polycarbonate cavity PCTFE Polychlorotriflu oroethylene (4) Short pressure retaining (4) -

Hybrid Effects in the Fracture Toughness of Polyvinyl Butyral‑Based Nanocomposites

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Hybrid effects in the fracture toughness of polyvinyl butyral‑based nanocomposites Shemer, Eldad; Hu, Xiao; Marom, Gad; Stern, Nadya; Dyamant, Itay 2018 Stern, N., Dyamant, I., Shemer, E., Hu, X., & Marom, G. (2018). Hybrid effects in the fracture toughness of polyvinyl butyral‑based nanocomposites. Nanocomposites, 4(1), 1‑9. doi:10.1080/20550324.2018.1447827 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/107018 https://doi.org/10.1080/20550324.2018.1447827 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Downloaded on 01 Oct 2021 05:17:18 SGT NANOCOMPOSITES, 2018 VOL. 4, NO. 1, 1–9 https://doi.org/10.1080/20550324.2018.1447827 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Hybrid effects in the fracture toughness of polyvinyl butyral-based nanocomposites Nadya Sterna, Itay Dyamantb, Eldad Shemerb, Xiao Huc and Gad Maroma aThe Casali Center of Applied Chemistry and the Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, The Institute of Chemistry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel; bOSG Armor R&D, Oran Safety Glass Ltd, Kibbutz Tzuba, Israel; cSchool of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Hybrid polyvinyl butyral (PVB) nanocomposite films comprising surface-treated carbon Received 3 January 2018 nanotubes (CNT-COOH) and nanoclays (NC) were tested for their “trouser-leg” fracture Accepted 27 February 2018 toughness in comparison to the values of the respective CNT and NC parent composites and to KEYWORDS that of the pristine PVB film. -

And Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Nanoparticles with BHK-21 Cell Line

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Understanding the interactions of poly(methyl methacrylate) and poly(vinyl chloride) nanoparticles with BHK‑21 cell line Gomathi Mahadevan & Suresh Valiyaveettil * Microplastic and nanoplastic particles are prevalent in the environment and are beginning to enter the living system through multiple channels. Currently, little is known about the impact of plastic nanoparticles in living organisms. In order to investigate the health impact of micro‑ and nanoparticles of common polymers in a systematic way, luminescent plastic nanoparticles from two common polymers, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with relatively narrow size distribution are prepared using a nanoprecipitation method. As a model system, BHK‑21 cells were exposed to polymer nanoparticles to understand the mode of uptake, internalization and biochemical changes inside the cells. The cellular efects of the nanoparticles were evaluated by monitoring the changes in cell viability, cell morphology, concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS), adenine triphosphate (ATP) and lactate dehydrogenase at diferent concentrations of the nanoparticles and time of exposure. PVC and PMMA nanoparticles induced a reduction in the cell viability along with a reduction of ATP and increase of ROS concentrations in a dose‑ and time‑dependent manner. The plastic nanoparticles are internalized into the cell via endocytosis, as confrmed by Dynasore inhibition assay and colocalization with latex beads. Our fndings suggest that plastic nanoparticle internalization could perturb cellular physiology and afect cell survival under laboratory conditions. Plastic waste accumulated in the environment undergoes slow degradation and disintegration under the ambient conditions and in presence of sunlight to generate smaller fragments called microplastics (size below 5 mm) or nanoplastics (below 1 µm)1,2.