Plaza Accord Unique?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angela Merkel Energy Security Spotlight on Africa

40 Years of Summits Inside: a special supplement focusing on four decades of debate and decision-making GERMANY: THE SCHLOSS ELMAU SUMMIT AN AUTHORISED PUBLICATION OF THE 2015 G7 SUMMIT Angela Merkel Germany’s Chancellor outlines the summit agenda Energy security Spotlight on Africa Creating a sustainable future A focus on the continent’s prospects and countering climate change for growth and development Sanofi_placed.indd 2 23/04/2015 11:42 Sanofi_placed.indd 3 23/04/2015 11:42 THE ANSWER IS BLOWING IN THE WIND Security of supply. Air pollution. Energy poverty. Unemployment. Climate change. Volatile fossil fuel prices. The world is full of problems. When shaping the society of tomorrow, we need to deal with all these problems at the same time. The good news is that to all these problems, there’s one solution. Wind energy is clean. It’s scalable. And most importantly, it’s competitive. Today, the cost of wind energy is lower than nuclear. Lower than gas. In some cases even lower than coal. And that’s before we add the costs of pollution. In short, the answer to many of our most pressing questions is literally blowing in the wind. €/MWh 125 100 75 50 25 0 Gas Coal Solar Nuclear Wind onshore Wind Source: ECOfys/European Commission solutionwind.com #solutionwind Clean. Competitive. Ready. European Wind Energy Association_placed.indd 1 13/05/2015 12:19 Contents G7 Germany: The Schloss Elmau Summit | June 2015 Introductions and leaders’ perspectives The G7 in numbers 10 40 years of G7 meetings — commitment for 38 A look at how the G7 members -

Building Better Global Economic Brics

Economics Global Economics Research from the GS Financial WorkbenchSM at https://www.gs.com Paper No: 66 Building Better Global Economic BRICs n In 2001 and 2002, real GDP growth in large emerging market economies will exceed that of the G7. n At end-2000, GDP in US$ on a PPP basis in Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC) was about 23.3% of world GDP. On a current GDP basis, BRIC share of world GDP is 8%. n Using current GDP, China’s GDP is bigger than that of Italy. n Over the next 10 years, the weight of the BRICs and especially China in world GDP will grow, raising important issues about the global economic impact of fiscal and monetary policy in the BRICs. n In line with these prospects, world policymaking forums should be re-organised and in particular, the G7 should be adjusted to incorporate BRIC representatives. Many thanks to David Blake, Paulo Leme, Binit Jim O’Neill Patel, Stephen Potter, David Walton and others in the Economics Department for their helpful 30th November 2001 suggestions. Important disclosures appear at the end of this document. Goldman Sachs Economic Research Group In London Jim O’Neill, M.D. & Head of Global Economic Research +44(0)20 7774 1160 Gavyn Davies, M.D. & Chief International Economist David Walton, M.D. & Chief European Economist Andrew Bevan, M.D. & Director of International Bond Economic Research Erik Nielsen, Director of New European Markets Economic Research Stephen Potter, E.D. & Senior Global Economist Al Breach, E.D & International Economist Linda Britten, E.D. -

3. IMF Article IV Consultations; 4. OECD Economic Surveys; 5

APENDICES 1. Additional plots and tables; 2. Business Cycle Chronologies; 3. IMF Article IV Consultations; 4. OECD Economic Surveys; 5. G20, G7 Summit Issues; 6. Compendium of Key Dates and Events; 7. Forecasts: Definitions and Sources 1 APPENDIX – ADDITIONAL PLOTS 2 Observed real GDP Growth Rates: Japan, U.S., and Germany Since 1960 (Quarterly) Real GDP Growth 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% -5% -10% -15% 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Germany Japan United States Annualized real GDP growth rates from FRED and supplemented with IMF IFS data. 3 Observed Inflation Rates: Japan, U.S., and Germany Since 1960 (Quarterly) Inflation rates 24% 20% 16% 12% 8% 4% 0% -4% 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Germany Japan United States Annualized CPI inflation rates. Sources same as previous figure. 4 Central Bank Policy Rates 20% 16% 12% 8% 4% 0% -4% 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Call rate - Japan Fedfunds - USA MRO - Eurozone In percent. Data from BIS. 5 Financial and Trade Globalization Financial Globalization 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 JPN USA DEU Trade Globalization 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 JPN USA DEU Data from KOF, see main text for link. -

The Federal Reserve Engages the World (1970–2000): an Insider’S Narrative of the Transition to Managed Floating and Financial Turbulence

Working Paper Series WP 14-5 AUGUST 2014 The Federal Reserve Engages the World (1970–2000): An Insider’s Narrative of the Transition to Managed Floating and Financial Turbulence Edwin M. Truman Abstract This paper traces the evolution of the Federal Reserve and its engagement with the global economy over the last three decades of the 20th century: 1970 to 2000. The paper examines the Federal Reserve’s role in international economic and financial policy and analysis covering four areas: the emergence and taming of the great inflation, developments in US external accounts, foreign exchange analysis and activities, and external financial crises. It concludes that during this period the US central bank emerged to become the closest the world has to a global central bank. JEL Codes: F3, F31, F32, F33, F34, E4, E42, F5, F52, F53 Keywords: Federal Reserve, Federal Open Market Committee, inflation, macroeconomic policies, monetary policy, external balance, exchange rates, exchange market intervention, financial crises, third world debt crises, Mexican crisis, Asian financial crises Edwin M. Truman, senior fellow since 2001, served as assistant secretary of the US Treasury for International Affairs from December 1998 to January 2001, and returned as counselor to the secretary from March–May 2009. He directed the Division of International Finance of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System from 1977 to 1998. He is the author, coauthor, or editor of Sovereign Wealth Funds: Threat or Salvation? (2010), Reforming the IMF for the 21st Century (2006), A Strategy for IMF Reform (2006), Chasing Dirty Money: The Fight Against Money Laundering (2004), and Inflation Targeting in the World Economy (2003). -

The Group of Seven

The Group of Seven We are now in the era of the G8, although the G7 still exists as a grouping for finance ministers and central bank governors. Why do G7 finance ministries and central banks co-operate? What are the implications of this for the power of the United States and the abilities of the other six states to exercise leadership? What influence do the G7 have on global financial governance? How much authority do they possess and how is that authority exercised? This is the first major work to address these fundamental questions. It argues that to understand the G7’s contribution to global financial governance it is necessary to locate the group’s activities in a context of ‘decentralized globalization’. It also provides original case study material on the G7’s contribution to macro- economic governance and to debates on the global financial architecture over the last decade. The book assesses the G7’s role in producing a system of global financial governance based on market supremacy and technocratic trans-governmental consensus and articulates normative criticisms of the G7’s exclusivity. For researchers in the fields of IR/IPE, postgraduate students in the field of international organization and global governance, policy-makers and financial journalists, this is the most comprehensive analysis of the G7 and financial governance to date. Andrew Baker is Lecturer at the School of Politics and International Studies at the Queen’s University of Belfast. He is the co-editor of Governing Financial Globalisation (Routledge, 2005) and has published in journals such as Review of International Political Economy and Global Governance. -

The Future of Central Bank Cooperation

1 The Future of Central Bank Cooperation Beth A. Simmons Harvard University Prepared for the BIS 75th Anniversary Conference June 27-29, Basel Revised Version: 6 November 2005 I would like to acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Alexander Noonan and Adrian Yung Hwei Ow. All errors remain my own. 2 The Future of Central Bank Cooperation Beth A. Simmons Harvard University Central bank cooperation has a long history. From the episodic efforts to support the 19th century gold standard to the personal interactions of interwar central bankers, to the institutionalized post-war efforts to maintain fixed exchange rates, to the post-Bretton Woods progress in developing standards for prudential bank regulation, central bankers have progressively consulted and coordinated their activities. Such cooperation has always been shaped by a few perennial parameters. Can they agree on theory (end-means relationships)? To what extent can central bankers agree on goals (social purpose)? Do they have the capacity (technical and institutional) to achieve their collective goals? Does the broader political environment facilitate or impede cooperation? It is easy to assume, in writing a paper on the “future of central bank cooperation”, that such cooperation is (1) easily observable (implicit in the assumption that a non-participant can meaningfully write about it), and (2) a good thing. Neither of these assumptions is without controversy, however. First, central bank cooperation is factually controversial. Looking over the historical record, there are important disagreements over whether, in fact, central bankers have cooperated at various historical moments. The passage of time does not seem to have settled the debate over whether, for example, central bankers in the 19th century were mutually cooperative or merely opportunistic.1 Much depends on how one defines cooperation. -

The Renminbi Exchange Rate Revaluation: Theory, Practice and Lessons from Japan

The Renminbi Exchange Rate Revaluation: Theory, Practice and Lessons from Japan Toshiki Kanamori (金森俊树) Zhijun Zhao (赵志君) March, 2006 Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-6008 Japan www.adbi.org ADBI Policy Paper No. 9 [email protected] © 2006 Asian Development Bank Institute. Knowledge Management Unit 3/06 ISBN: 4-89974-010-7 The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views or position of the ADB Institute, its Advisory Council, Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. The ADB Institute does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included and accepts no responsibility for any consequences arising from its use. The word “country” or other geographical names do not imply any judgment by the ADB Institute as to the legal or other status of any entity, including its borders. About the authors Toshiki Kanamori is Director, Administration, Management and Coordination of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI). He graduated from Hitotsubashi University as well as from New Asia and Yale Center of Chinese University of Hong Kong. During his government career he served with Japan’s Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of International Trade and Industry. He was an Alternate Director at ADB HQ from 1990 to 1993. Before joining the ADBI, he was a Visiting Fellow at the China Business Centre (CBC), Hong Kong Polytechnic University. He has published many articles on the PRC economy as well as on global socio-economic issues. Zhijun Zhao is professor and senior researcher of the Institute of Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). -

German Monetary Policy in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century

German Monetary History in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century: From the Deutsche Mark to the Euro Robert L. Hetzel tarting in January 2002, citizens of the European Monetary Union (EMU) replaced their national currencies with the Euro, issued by the S European Central Bank (ECB). Europeans created a new pan-European central bank as a symbol of a future united Europe. However, what historical process explains the broad monetary policy of the ECB, that is, its objective of price stability and its strategy for achieving that objective? The short answer is that its founders designed the ECB to look like the Bundesbank. How then did the Bundesbank evolve? To answer that question, I survey German monetary policy in the second half of the twentieth century. I divide this history into three main sections.1 The first treats the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. The second treats the floating exchange rate period that began in 1973. It chronicles the Bundesbank’s ultimate deci- sion to accord primacy to reducing inflation rather than unemployment. The last explains how the Bundesbank dealt with the pressures created by move- ment toward a single European currency. The evolution of the Bundesbank into an institution now identified as a modern central bank is fundamental to the article. A modern central bank This article follows Hetzel (2002), which summarizes German monetary policy in the first half of the twentieth century. The author gratefully acknowledges helpful comments from Michael Dotsey, Martin M. Fase, Andreas Hornstein, Thomas Humphrey, Joachim Scheide, and Alex Wolman. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System. -

Time for a Plaza II?

14 Time for a Plaza II? C. FRED BERGSTEN The Plaza-Louvre in Retrospect The Plaza Accord of September 1985—and its successor Tokyo Summit and Louvre Accord over the following 18 months—represents the high-water mark of international economic policy cooperation and indeed coordination over the entire postwar period.1 These agreements created a model that has not been replicated during the past 30 years. Numerous other international efforts have been undertaken to correct current account imbalances and currency disequilibria. They have taken place under both fixed and flexible exchange rates, both before and after the Plaza- Louvre. A number of emergency meetings of the G-10 sought to resolve sterling crises in the 1960s. The Franco-German imbalance was addressed in 1968–69. Much more prominently, the 1971 Smithsonian Agreement established a new set of parities after the United States suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold and adopted an import surcharge. C. Fred Bergsten was founding director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics from 1981 through 2012 and is now senior fellow and director emeritus there. The comments of William Cline, Charles Dallara, Jeffrey Frankel, Joseph Gagnon, Ted Truman, and John Williamson on earlier drafts of this chapter are greatly appreciated. Abir Varma provided invaluable research assistance. 1. This account of the Plaza-Louvre draws heavily on the defi nitive study of the period by Yoichi Funabashi (1989). Funabashi interviewed all but one of the ministers and central bank governors who negotiated the agreement (including Secretary James Baker, Assistant Secretary (later Under Secretary) David Mulford, Assistant Secretary Charles Dallara, and Fed Chairman Paul Volcker and his chief lieutenant, Ted Truman) as well as a who’s who of other government offi cials and outside observers. -

Explaining Compliance with International Commitments to Combat Financial Crisis: the IMF and the G7

Explaining Compliance with International Commitments to Combat Financial Crisis: The IMF and the G7 Ivan Savic Ph.D. Candidate Columbia University Presented at: 47th Annual ISA Convention San Diego, CA March 22-25, 2006 Panel: WD34 Wednesday 3:45 - 5:30 PM Explaining Compliance with International Economic Commitments Across the North-South Divide 1 Abstract: G7 commitments are a crucial element of international efforts to combat financial crises. The members of the G7 are the source of much of the world’s capital. Through individual action, regular coordination through Summits and Finance Minister Meetings, and their large voting shares in the IMF they effectively regulate and structure the international financial architecture. Finally, the G7 regularly supports and often supplements the efforts of the IMF to contain and reverse financial crisis. This paper will examine the relationship between the G7 and the IMF and how it affects the ability of both organizations to deal with crises. Specifically it will look at the influence of the G7 in the IMF and how the G7 coordinates and works with the IMF in crisis response. The paper will develop a model of coordination among the G7 and between the G7 and the IMF and then look at the record of their commitments since 1975 and the G7’s role in bailouts such as those created in response to the Asian Crisis of 1997/98. 1 Introduction Financial crises have been a long-standing issue in the international financial system and have in fact been around since it emerged in the late 1800s. As the international system has developed and become more sophisticated, numerous institutional efforts have been made to prevent the outbreak of financial crises. -

Monetary Policy Cooperation/Coordination and Global Financial Crises in Historical Perspective

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MONETARY POLICY COOPERATION/COORDINATION AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISES IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Michael D. Bordo Working Paper 27898 http://www.nber.org/papers/w27898 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2020 Paper prepared for the conference “From Bretton Woods to 2008 and Beyond: Global Monetary Governance” Brussels, Belgium September 18 2020 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2020 by Michael D. Bordo. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Monetary Policy Cooperation/Coordination and Global Financial Crises in Historical Perspective Michael D. Bordo NBER Working Paper No. 27898 October 2020 JEL No. E58,F33,N20 ABSTRACT The COVID-19 pandemic spawned a global liquidity crisis in March 2020. The global liquidity crisis was alleviated by the Federal Reserve and other advanced country central banks cooperating by extending the swap lines they developed in the Global Financial Crisis 2007-2008. Central bank cooperation in 2020 evolved from a two-century history across several monetary regimes that is surveyed in this paper. I find that in monetary regimes which are rules- based cooperation was most successful. International currency swaps developed to manage exchange rates during the Bretton Woods era have evolved into the leading tool to manage international liquidity crises. -

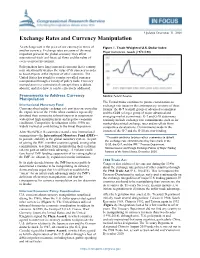

Exchange Rates and Currency Manipulation

Updated December 31, 2020 Exchange Rates and Currency Manipulation An exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of Figure 1. Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index another currency. Exchange rates are some of the most Major Currencies, Goods (1973=100) important prices in the global economy: they affect international trade and financial flows and the value of every overseas investment. Policymakers have long expressed concerns that a country may intentionally weaken the value of its currency in order to boost exports at the expense of other countries. The United States has sought to counter so-called currency manipulation through a variety of policy tools. Currency manipulation is a controversial concept; there is debate about if, and if so how, it can be effectively addressed. Frameworks to Address Currency Source: Federal Reserve. Manipulation The United States continues to pursue coordination on International Monetary Fund exchange rate issues in the contemporary versions of these Concerns about unfair exchange rate practices are rooted in forums: the G-7 (a small group of advanced economies) the experiences of the 1930s, when countries repeatedly and the G-20 (a larger group of major advanced and devalued their currencies to boost exports in response to emerging-market economies). G-7 and G-20 statements widespread high unemployment and negative economic routinely include exchange rate commitments, such as for conditions. Competitive devaluations of the 1930s are market-determined exchange rates and to refrain from widely viewed as contributing to the Great Depression. competitive devaluations. Commitments made in the After World War II, countries created a new international context of the G-7 and the G-20 are non-binding.