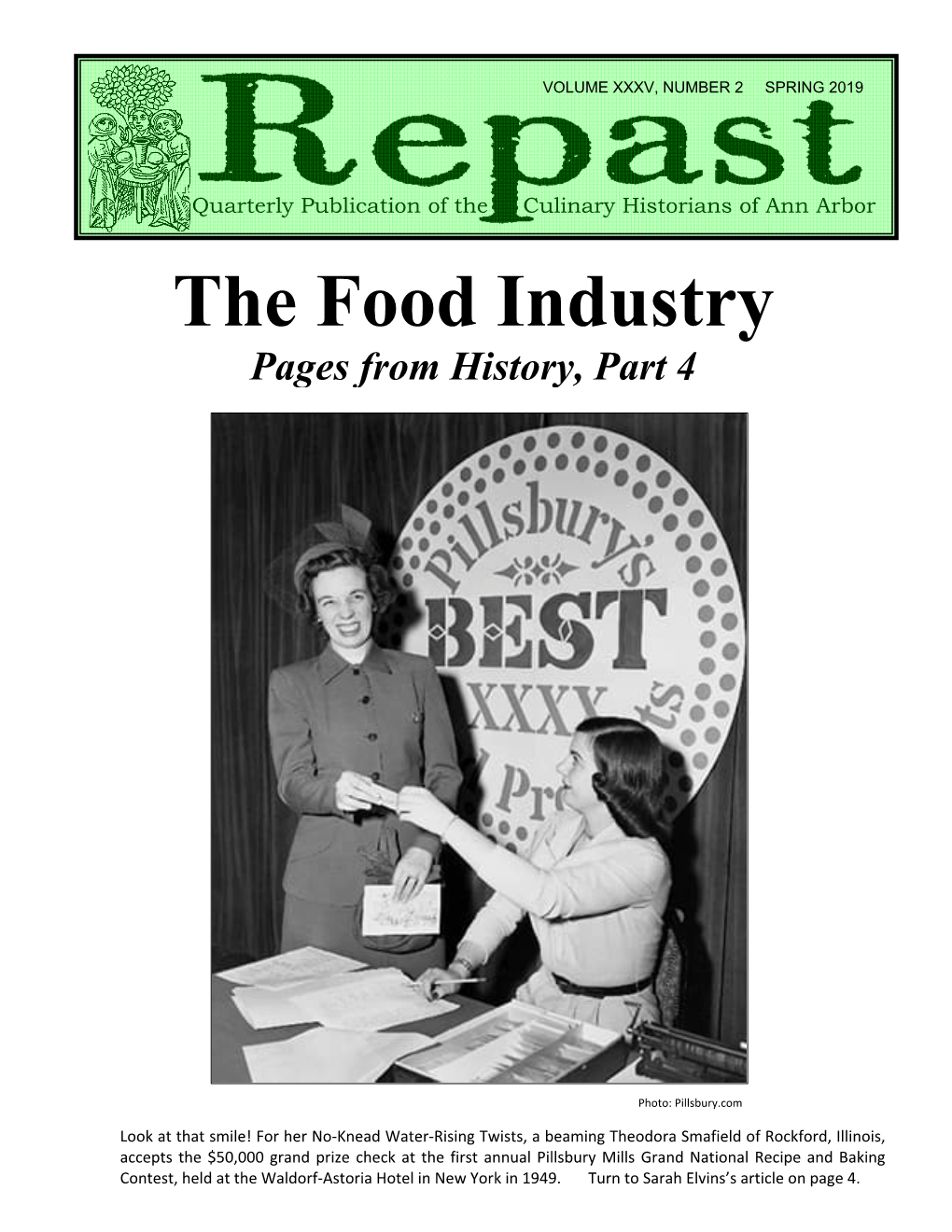

The Food Industry Pages from History, Part 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT for the DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017

Photo Credit: Mercy Corps MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT FOR THE DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 METHODOLOGY 4 TARGET POPULATION 4 JUSTIFICATION FOR MARKET SELECTION 4 AREA OVERVIEW 5 MARKET SYSTEM MAP 9 CONSUMPTION & DEMAND ANALYSIS 9 SUPPLY ANALYSIS & PRODUCTION POTENTIAL 12 TRADE FLOWS 14 MARGINS ANALYSIS 15 SEASONAL CALENDAR 15 BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 17 OTHER INITATIVES 20 KEY FACTORS DRIVING CHANGE IN THE MARKET 21 RECOMMENDATIONS & SUGGESTED INTERVENTIONS 21 MERCY CORPS Market System Assessment for the Dairy Value Chain: Irbid & Mafraq 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The dairy industry plays an important role in the economy of Jordan. In the early 70’s, Jordan established programmes to promote dairy farming - new breeds of more productive dairy cows were imported, farmers learned to comply with top industry operating standards, and the latest technologies in processing, packaging and distribution were introduced. Today there are 25 large dairy companies across Jordan. However inefficient production techniques, scarce water and feed resources and limited access to veterinary care have limited overall growth. While milk production continues to steadily increase—with 462,000 MT produced (78% of the market demand) in 2015 according to the Ministry of Agriculture—the country is well below the production levels required for self-sufficiency. The initial focus of the assessment was on cow milk, however sheep and goat milk were discovered to play a more important role in livelihoods of poor households, and therefore they were included during the course of the assessment. Sheep and goats are better adapted to a semi-arid climate, and sheep represent about 66 percent of livestock in Jordan. -

MENU Prix TTC En Euros

Cold Mezes Hot Mezes Hummus (vg) ............................... X Octopus on Fire ............................ X Lamb Shish Fistuk (h) .................. X Chickpeas, tahini, lemon, garlic, Smoked hazelnut, red pepper sauce Green pistachio, tomato, onion, green sumac, olive oil, pita bread chilli pepper, sumac salad Moroccan Rolls ............................. X Tzatziki (v) ................................... X Filo pastry, pastirma, red and yellow Garlic Tiger Prawns ...................... X Fresh yogurt, dill oil, pickled pepper bell, smoked cheese, harissa Garlic oil, shaved fennel salad, red cucumber, dill tops, pita bread yoghurt chilli pepper, zaatar Babaganoush (vg) ......................... X Pastirma Mushrooms .................... X Spinach Borek (v) ......................... X Smoked aubergine, pomegranate Cured beef, portobello and oysters Filo pastry, spinach, feta cheese, pine molasses, tahini, fresh mint, diced mushrooms, poached egg yolk, sumac nuts, fresh mint tomato, pita bread Roasted Cauliflower (v) ................ X Chicken Mashwyia ........................ X Taramosalata ................................ X Turmeric, mint, dill, fried capers, Wood fire chicken thighs, pickled Cod roe rock, samphire, bottarga, garlic yoghurt onion, mashwyia on a pita bread lemon zest, spring onion, pita bread Grilled Halloumi (v) ..................... X Meze Platter .................................. X Beetroot Borani (v) ...................... X Chargrilled courgette, kalamata Hummus, Tzatziki, Babaganoush, Walnuts, nigella seeds, -

Dessert Menu

MADO MENU DESSERTS From Karsambac to Mado Ice cream: Flavor’s Journey throughout the History From Karsambac to Mado Ice-cream: Flavors’ Journey throughout the History Mado Ice-cream, which has earned well-deserved fame all over the world with its unique flavor, has a long history of 300 years. This is the history of the “step by step” transformation of a savor tradition called Karsambac (snow mix) that entirely belongs to Anatolia. Karsambac is made by mixing layers of snow - preserved on hillsides and valleys via covering them with leaves and branches - with fruit extracts in hot summer days. In time, this mixture was enriched with other ingredients such as milk, honey, and salep, and turned into the well-known unique flavor of today. The secret of the savor of Mado Ice-cream lies, in addition to this 300 year-old tradition, in the climate and geography where it is produced. This unique flavor is obtained by mixing the milk of animals that are fed on thyme, milk vetch and orchid flowers on the high plateaus on the hillsides of Ahirdagi, with sahlep gathered from the same area. All fruit flavors of Maras Ice-cream are also made through completely natural methods, with pure cherries, lemons, strawberries, oranges and other fruits. Mado is the outcome of the transformation of our traditional family workshop that has been ice-cream makers for four generations, into modern production plants. Ice-cream and other products are prepared under cutting edge hygiene and quality standards in these world-class modern plants and are distributed under necessary conditions to our stores across Turkey and abroad; presented to the appreciation of your gusto, the esteemed gourmet. -

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies Yoghurt Partially Supplemented with Barley Flour fermented with Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum BB536 الزبادي المدعم جزئيا بدقيق الشعير المخمر بالبكتريا الصديقة Bifidobacterium longum BB536 Dissertation Submitted to Sudan University of Science and Technology in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Food Science and Technology By Manal Ahmed Mustafa Mohammed B.Sc. (Honors) in Food Science and Technology, Sudan University of Science and Technology (2010) Supervisor Associated Professor Dr. Barka Mohammed Kabier Barka Department of Food Science and Technology, College of Agriculture Studies, SUST October 2017 2 اﻵية قال تعالي: )وَإِنَّ لَكُمْ فِي الْأَنْعَامِ لَعِبْرَةً نُسْقِيكُمْ مِمَّا فِي بُطُونِهِ مِنْ بَيْنِ فَرْثٍوَدَمٍ لَبَنًا خَالِصًا سَائِغًا لِلشَّاِِبِينَ( صدق اهلل العظيم سوِة النحل اﻵية )66( I Dedication this dissertation is dedicated to soul of my late father Ahmed Mustafa To dear my mother Nafisa Khalid To my dear Grandmother To my dear Aunts and Uncles To my dear Brothers and sisters To my all Relative for their kind helps and support II Acknowledgment First, almost grateful thanks to Allah for giving me health, patience, and assistance to complete this work. Thanks and all thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Barka Mohamed Kabeir Barka for supervising and nice cooperation and help. Especially thanks to my dear Ustaza Eshraga and all staff at animal production department for kind help and support. Finally thanks to my -

To-Go Menu SALADS with GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET

SAMPLERS ATHENA’S WRAPS *ADD HUMMUS AND SALAD FOR $2* V DIP SAMPLER ......................................... 7 HUMMUS, GRECIAN DIP, BABA GHANOUSH & LABNEH CHICKEN SHAWERMA ............................... 7 8 ATHENA’S SAMPLER FOR ONE ................ 7 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE & TOMATOES FALAFEL, FRIED EGGPLANT, KIBBEH & MEAT GRAPE LEAF GYRO .............................................................. 7 8 GREEK MEZA V ......................................... 4 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, ONIOINS, TURNIPS, PICKLES & OLIVES BEEF KOFTA ................................................ 7 MEAT FEAST ................................................. 25 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS CHOOSE FIVE DIFFERENT SKEWER ITEMS BEEF SHAWERMA STREET ....................... 11 GRILLED 12-INCH BEEF WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED To-Go Menu SALADS WITH GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET .............. 10 GRILLED 12-INCH CHICKEN WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED FETA SALAD .................................................. 6 WITH GARLIC SAUCE LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE & ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING HALLOUMI CHEESE V ........................... 8 GREEK SALAD ............................................... 7 DRIED MINT, TOMATOES & BLACK OLIVES LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE, TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, BLACK OLIVES & EGGPLANT V ............................................. 8 ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING ARABIC SALAD .............................................. 7 FETA CHEESE, ONIONS & TOMATOES V HOURS FRESH-CUT TOATOES, CUCUMBERS, PARSLEY, -

Eastern Mediterranean Know Before You Go

Eastern Mediterranean Know Before You Go A step by step guide to your Trafalgar trip. Your insider’s journey begins… Thank you for choosing Trafalgar to show you the insider’s view of the Eastern Mediterranean. A wealth of experience has taught us that your journey begins well before you leave home. So we have compiled this guide to provide you with as much information as possible to help you prepare for your travels. We look forward to welcoming you on the trip of a lifetime! Temple of Zeus and Acropolis, Greece 2 Before you go… Travel Documents Other benefits include: A couple of weeks prior to your vacation you will receive your • You won’t be required to show your passport at each hotel Trafalgar wallet with your travel documents and literature. • Your Travel Director will have all your important These documents are valuable and contain a wealth of advice details immediately and essential information to make your vacation as enjoyable • You’ll receive useful information and tips before you go as possible. Please read them carefully before your departure. and compelling offers from our partners Passports and Visas It should take less than 10 minutes to register and you should have the following information ready: You will require a passport valid for six months beyond the • Your booking number and last name conclusion of your trip, with appropriate visas. Some itineraries • The passport details of everyone on your booking may require multiple-entry visas for certain countries. You • The emergency contact details of your nominated person must contact your travel agent or applicable government (should an unlikely event arise) authorities to get the necessary documentation. -

Isolation and Characterization of Bacteriophages from Laban Jameed

Food and Nutrition Sciences , 2013, *, **-** doi:10.4236/fns.2013.***** Published Online *** 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns) Isolation and Characterization of Bacteriophages from Laban Jameed Murad Mohammad Ishnaiwer and FawziAl-Razem * Biotechnology Research Center, Palestine Polytechnic University, P.O.BOX 198, Hebron, Palestine. *Email: [email protected] Received July 25, 2013. ABSTRACT Laban jameed is a dried salty dairy product obtained by fermentation of milk using a complex population of lactic acid bacteria. Jameed is considered a traditional food product in most eastern Mediterranean countries and is usually made from sheep or cow milk. The aim of this study was to assess phage contamination of jameed dairy product. Two phages were isolated; one from sheep milk jameed (PPUDV) and the other from cow milk jameed (PPURV). Each of the two bacteriophages was partially characterized. The PPUDV phage was identified as a single stranded DNA virus with an approximately 20 kb genome that was resistant to RNase, whereas PPURV phage possessed a double stranded RNA genome of approximately 20 kb and was resistant to DNase. The phage bacterial strain hosts were identified as Lactoba- cillus helveticus and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens for PPUDV and PPURV, respectively. One step growth curve using a double layer plaque assay test was carried out to monitor the phage life cycle after host infection. PPUDV showed a latent period of about 36 h, burst period of 70 h and a burst size of about 600 Plaque Forming Units (PFU) per infected cell. PPURV phage showed latent period of about 24 h, burst period of 47 h and a burst size of about 700 PFU per infected cell. -

Traditional Dairy Products in Algeria: Case of Klila Cheese Choubaila Leksir1, Sofiane Boudalia1,2* , Nizar Moujahed3 and Mabrouk Chemmam1,2

Leksir et al. Journal of Ethnic Foods (2019) 6:7 Journal of Ethnic Foods https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0008-4 REVIEW ARTICLE Open Access Traditional dairy products in Algeria: case of Klila cheese Choubaila Leksir1, Sofiane Boudalia1,2* , Nizar Moujahed3 and Mabrouk Chemmam1,2 Abstract The cheese Klila occupies a very important socio-economic place established in the rural and peri-urban environment. It is a fermented cheese produced empirically in several regions of Algeria. It is the most popular traditional cheese and its artisanal manufacturing process is still in use today. The processing consists of moderate heating of “Lben” (described a little farther) until it becomes curdled, and then drained in muslin. The cheese obtained is consumed as it stands, fresh, or after drying. When dried, it is used as an ingredient after its rehydration in traditional culinary preparations. In this review, we expose the main categories of traditional Algerian dairy products; we focus mainly on the traditional Klila cheese, its history, origin, and different manufacturing stages. We recall the different consumption modes and incorporation of Klila cheese in the culinary preparations. Keywords: Traditional cheese, Klila, Terroir Introduction Traditional dairy products in Algeria In Algeria, the consumption of dairy products is an old History and origin of cheeses tradition linked to livestock farming, since dairy prod- According to Fox and McSweeney [9], the word “cheese” ucts are made by means of ancient artisanal processes, comes from the Latin “formaticus” meaning “what is using milk or mixtures of milk from different species done in a form.” The discovery of cheese was probably [1–4]. -

Handle with Care

Herfst 08 Handle with Care The Future of Europe What will the Common Future of all countries involved in the project look like? A cooperation of Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Norway and Scotland that offers a window on the future… Texts produced by students from Urspringschule (Schelklingen), Wallace Hall Academy (Dumfries), Xantus Janosschool (Budapest), Fjölbrautaskolinn i Breidholti (Reykjavik), Heilig-Hartcollege Waregem (Waregem), Vidagrande skule (Sykkylven), … (Kazanlak) Photography: Jòhann Finnur Common Roots – Common Future 1 Table of contents 3 International Food Recipes 6 Interview Ingrid Van Der Velde 8 A dream for the future 10 Icelandic proverbs 10 A discussion about food 15 Our daily food – Belgian edition 18 10 Tips of healthy eating habits 21 Food comparison 22 Our daily food – German edition 24 Fast Food 26 Apples all over the world 29 Interview with Mario Blessing 32 Food migration 33 Ways of producing energy 34 Article from Jamie Oliver 35 Mass Farming 36 German Proverbs 37 Organic Certification 2 International recipes Hot Dog Ingredients 1 all-beef hot dog 1 poppyseed hot dog bun 1 tablespoon yellow mustard 1 tablespoon sweet green pickle relish 1 tablespoon chopped onion 4 tomato wedges 1 dill pickle spear 2 sport peppers 1 dash celery salt Directions 1. Bring a pot of water to a boil. Reduce heat to low, place hot dog in water, and cook 5 minutes or until done. Remove hot dog and set aside. Carefully place a steamer basket into the pot and steam the hot dog bun 2 minutes or until warm. 2. Place hot dog in the steamed bun. -

Ebook Download 20 Best Mouth Watering Desserts from Around

20 BEST MOUTH WATERING DESSERTS FROM AROUND THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Juliana Blossom | 72 pages | 27 Nov 2019 | Independently Published | 9781712596548 | English | none 20 Best Mouth Watering Desserts From Around The World PDF Book It's the fruit of my nine years in the pastry kitchen, when I traveled to explore new-to-me flavors everywhere from Liguria, Italy, to Yucatan, Mexico, and conversations with chefs whose resumes are as global as the recipes themselves. These light-as-a-feather confections are one of the most mouthwatering gifts France has offered to the world. Cold eggs, milk, sugar, blackberries, rum and, possibly cocoa blend together. Pair it with a glass of almond milk to really feel like a kid again! Tub Tim Krob, Thailand. Although they are popular in Pakistan and Nepal. Even thinner than filo, the delicate warqa dough that's used for this Moroccan sweet is prepared by daubing a ball of dough on a hot griddle; it's an impressive labor of love that takes deft hands and many hours of practice. Below you can find some familiar yet still favorable classic Oreo cake recipes. These little puffs of choux pastry, sprinkled with pearl sugar, are crisp, airy, and simply irresistible. The melted cheese and warm dough create a savory and sweet mixture of tastes unique only to kanafeh. A soft, flaky dough is shaped into a plump half-moon that barely contains the sweet filling, then topped with a light blanket of powdered sugar. Dark rounds of chocolate cake are doused in a cherry syrup spiked with kirschwasser, a sour cherry brandy, then stacked atop a thin, chocolate base with deep layers of whipped cream and fresh cherries. -

Appetizers Salads Entrees Sandwiches Desserts Sides (720)

G A R R T E E I N B To place your order, call: (720) 328-8328 Y S O IN U U R H A Appetizers Entrees Polish Pierogies boiled or fried, stuffed with Bohemian Beef Goulash made w/ finely cut cheese & potato or spinach & feta or pork. Garnished pieces of beef, paprika, sourcream and onion sauce with mushrooms, onions, garlic and red pepper flake. and served w/ classic Czech bread dumplings. $18 Served with a side of spicy pierogi sauce. $12 Chicken or Pork Schnitzel topped w/ lemon Housemade Country Style Pate warm & capers, served w/ potato salad and choice of Baguette, gherkin pickles, house spicy mustard. $12 cucumber or beet salad. $16 Giant Pretzel with house made mustards. $8 Sausage Plates choice of knackwurst, polish + haus bier cheese $1 kielbasa, housemade bratwurst, smoked german bratwurst or weisswurst and served w/ sauerkraut, Pretzel Sausage frankfurter wrapped in a butter fries, pretzel bread. $12 glazed pretzel roll served with sauerkraut $9 + haus bier cheese $1 Crispy Czech Style Gnocchi $17 Choice of: Crispy bacon, gruyere and sour cream or Haus Deviled Eggs red onion, dill pickle and Forest mushroom ragout, gruyere and chives(v) chive oil. Crispy bacon optional. $9 Fish & Chips wild caught pangasius fried in our Seasonal Soup either hot or cold depending on the house made bier batter. Served with tarter sauce, weather. Please ask server for details. MP coleslaw and fries. $18 Handcut Steak Tartare black angus filet mignon, Jager Schnitzel choice of either chicken or pork. traditional seasonings, crispy shallots and toasted Served with creamy mushroom sauce, red cabbage baguette. -

Salads Appetizers Sandwiches Saj Wraps

Salads 1. Wally’s Salad – $6.99 4. Gyro Salad – $8.99 A delicious blend of lettuce, onion, cucumber, Our delicious Jerusalem salad topped with gyro tomato and chickpeas, topped with our house salad meat. Served with 1 side of cucumber sauce. dressing. 5. Falafel Salad – $7.99 1 2. Jerusalem Salad – $7.45 A delicious blend of lettuce, onion, cucumber, A delicious blend of lettuce, onion, cucumber, tomato, chickpeas, fried cauliflower, fried pita bread, tomato, chickpeas, feta cheese, black olives, topped falafel, topped with our tahini sauce dressing. with our house salad dressing. 6. Tabouli Salad – $7.45 3. Chicken Shawarma Salad – $8.99 Minced parsley, chopped tomatoes, green onions, Our delicious Jerusalem salad topped with chicken 4 and crushed wheat (bulgar) tossed together with shawarma meat. Served with 1 side of garlic sauce. olive oil and lemon juice. Appetizers 7. Hummus – $6.35 10. Veggie Samosas – $6.49 Wally’s homemade hummus is so good you’ll want 6 cocktail pieces of Wally’s special dough stuffed to bring some home! Mashed chickpeas blended 8 with ground chickpeas, onion, peas, green chili with tahini sauce, lemon juice and garlic, served peppers and mix spices, then deep fried. Served with 2 pitas. with 1 cucumber sauce. 8. Wally’s Falafel and Hummus Plate – $8.45 11. Arayes – $7.49 Tradition on a plate. 4 pieces of falafel on top of our Our homemade pita stuffed with ground beef mixed homemade hummus, served with 2 pitas. with hot spicy herbs then baked to perfection. Served with 1 tahini sauce. 10 9.