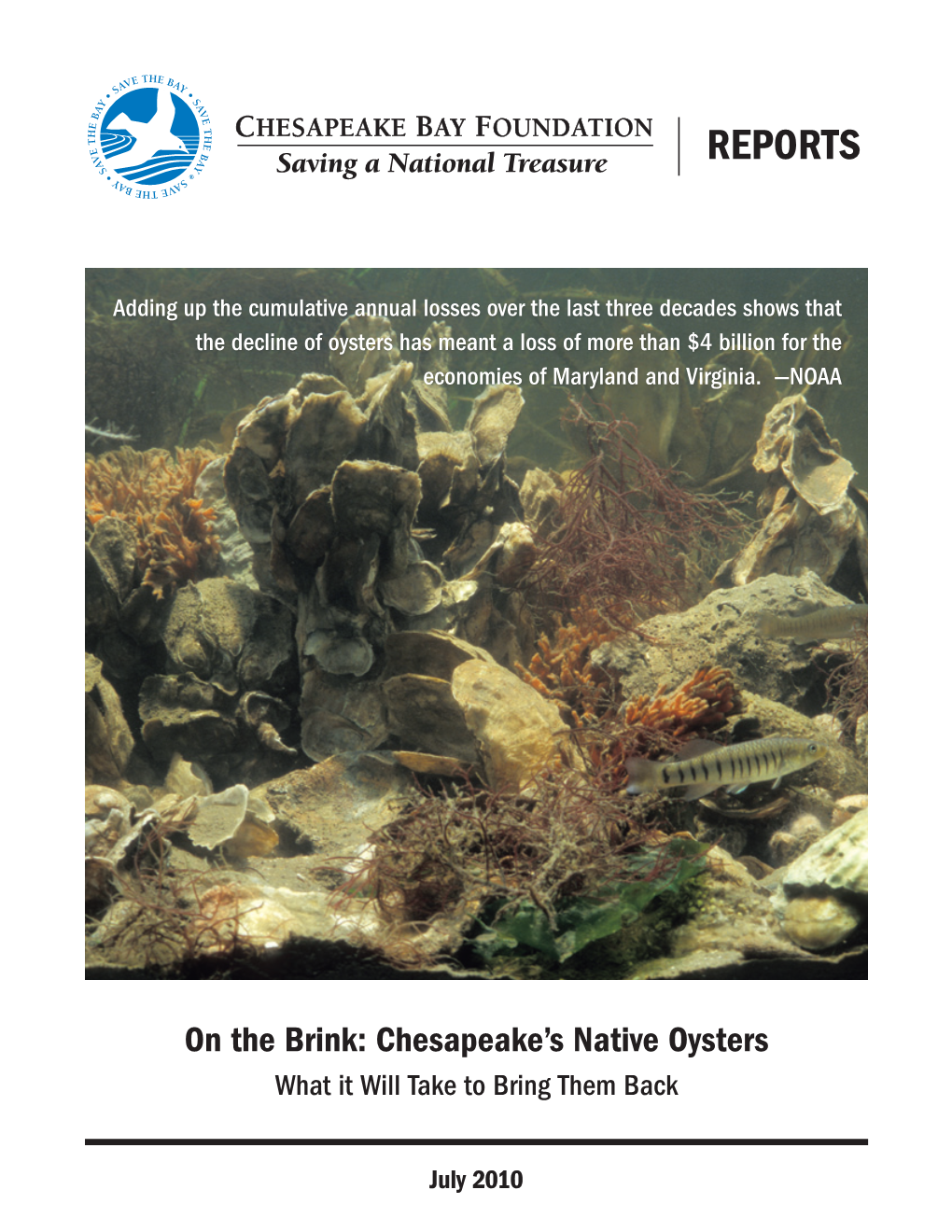

On the Brink: Chesapeake's Native Oysters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Related Regulations: Which Government Agency Is Responsible?

Water Related Regulations: Which Government Agency Is Responsible? Overview (The information in this section was modified from the Virginia Water Resources Research Center’s “For the Record,” Virginia Water Central, April 2000, April 2004, and August 2004 editions) Federal Water Regulations Federal regulations cover drinking water safety, water quality in the nation’s water bodies, use of navigable waters, wetlands activities, interstate transportation on waterways, certain dams and dam related activities, and many other areas. Existing Regulations The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) compiles the rules published in the Federal Register. The CFR is divided into 50 titles covering broad areas. Title 40, for example, is “Protection of the Environment” and contains many EPA regulations. Internet users should go to http://www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/index.html for an index of, and links to, all the CFR titles. For paper copies of CFR titles (for a charge), contact the U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO) Access Order Desk at (866)-512-1800 or [email protected]. Agencies Appearing in the Code of Federal Regulations The alphabetical list of agencies with pertinent CFR titles can be found in “Appendix C” of the U.S. Government Manual at www.gpoaccess.gov/gmanual/index.html. Internet sites for regulatory information from some key water- related federal agencies are listed below (addresses correct as of 7/15/05): Environmental Protection Agency – www.epa.gov/epahome/rules.html. Army Corps of Engineers – www.usace.army.mil/public.html#Regulatory. Fish and Wildlife Service – laws.fws.gov. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission – www.ferc.gov/legal/ferc-regs.asp. -

Table of Contents

Member Agency Report‐Outs for November 2018 RRT III Meeting Table of Contents 1. Federal On‐Scene Coordinators (FOSCs): USEPA ........................................................................................................................................ (4 pages) USCG Sectors / MSUs: Sector Delaware Bay .......................................................................................................... (2 pages) Sector Maryland – NCR ...................................................................................................... (3 pages) Sector Hampton Roads ...................................................................................................... (3 pages) Sector Buffalo ..................................................................................................................... (2 pages) Sector North Carolina .......................................................................................................... (1 page) MSU Huntington .................................................................................................................. (1 page) MSU Pittsburgh .................................................................................................................... (1 page) 2 States/Commonwealths: Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control .................. verbal report only District of Columbia Department of Energy & Environment ..................................................... no report Maryland Department of the Environment ............................................................... -

18476 MINUTES COMMISSION MEETING January 28, 2020 the Meeting of the Marine Resources Commission Was Held at the Marine Reso

18476 MINUTES COMMISSION MEETING January 28, 2020 The meeting of the Marine Resources Commission was held at the Marine Resources Commission main office at 380 Fenwick Road, Bldg. 96, Fort Monroe, Virginia with the following present: Steven G. Bowman Commissioner Wayne France John Tankard III John Zydron Sr. Ken Neill, III Associate Members Heather Lusk James E. Minor III Chad Ballard Christina Everett Kelci Block Assistant Attorney General Lou Atkins Recording Secretary Erik Barth Bs. Systems Manager Dave Lego Bs. Systems Specialist Sheri Crocker Chief, Admin. & Finance Management Pat Geer Chief, Fisheries Mgmt. Adam Kenyon Deputy Chief, Fisheries Mgmt. Shanna Madsen Deputy Chief, Fisheries Mgmt. Andrew Button Head, Conservation and Replenishment Stephanie Iverson Fisheries Mgmt. Manager, Sr. Alicia Nelson Coordinator, RFAB/CFAB Ethan Simpson Biological Sampling Program Manager Chris Davis Fisheries Biologist Jill Ramsey Fisheries Mgmt. Specialist Alexa Kretsch Fisheries Mgmt. Specialist Somers Smott Fisheries Mgmt. Specialist Olivia Phillips Fisheries Mgmt. Specialist Hank Liao Lab Manager Jessica Gilmore Lab Specialist 18477 Commission Meeting January 28, 2020 Rick Lauderman Chief, Law Enforcement Warner Rhodes Deputy Chief, Law Enforcement James Vanlandingham Marine Police Officer Alan Squires Marine Police Officer Barry Mizelle Marine Police Officer Patrick West Marine Police Officer Tony Watkinson Chief, Habitat Management Randy Owen Deputy Chief, Habitat Management Justin Worrell Environmental Engineer, Sr. Jay Woodward Environmental -

Rappahannock Record, March 14, 2013, Section D

Section D Rappahannock Record Kilmarnock, VA MarketPlace March 14, 2013 2EAL%STATEs0UBLIC.OTICESs"USINESS$IRECTORY www.rrecord.com CALL US! Monday-Friday, 9 am to 5 pm, 804. 435.1701 or (toll-free in VA) 1.800.435.1701. FAX your ad to 804.435.2632. E-MAIL your ad to [email protected]. ONLINE: Submit your ad 24 hours a day at www.RRecord.com (click on “Classifieds” in the top menu and then “Click here to submit your classified ad online.”) Call or go online now to easily place your classified ad. Real Estate Real Estate Real Estate Lots/Acreage 1.5 ACRES SURROUND 3BR/2 CARTERS CREEK WEEMS WATER ACCESS home & 26’x24’ LAND story Lancaster Co. farmhouse. DRASTIC REDUCTION! garage. 1982 2BR/1BA single wide Lancaster Porch, utility room, + extra storage. $199,000 in Bay Quarter Shores. Access *Dymer Creek, 3.4 acres, Needs paint, insulation, carpet. 611 JOHNS NECK to sand beach, boat ramp, pool, 9’MLW $595,000 IsaBell K. Horsley $48,900 (really!) Kane & Associates, 2BR/1.5BA tennis, playground, fishing piers, *Rap. River two lots Inc. (c)804-580-0327..(Mar-14-13t) WATERFRONT, SHARED PIER club house. $59,000. 804-529- Site plan $225,000 each *Heritage Point, Community TERRI GROH 7833..(March-7-2t) Real Estate, Ltd 1.75/ACRES, 3BR/COLONIAL, wrap Amenities 1 acre $17,500 around screened porch, mature REMAX WATERFRONT REALTY WATERFRONT PROPERTY. NORTHUMBERLAND landscaping. 1900SF of classic KILMARNOCK, VA Buying or Selling. www.northern- Chesapeak Cove Cubbitt Creek charm, 9’/ceilings. 3 outbuildings. 804-436-7874 neckrealtors.com..(Feb-14-13t) 1.9 ac/waterfront $95,000 www.HorsleyRealEstate.com Lancaster County. -

Police Reports Sure Evacuees Remain Eligible a Hoist Has Provided Search and for Federal Emergency Manage- Rescue Support

Section VMRC addresses • B • boathouse project, non-native oysters September 8, 2005 and rockfi sh season NEWPORT NEWS—At its base management measures, KILMARNOCK, VIRGINIA August 23 meeting, the Virginia the commission established new Marine Resources Commission regulations for fall 2005. heard eight habitat permit cases, The recreational season will two items related to submerged begin October 4 and extend aquatic vegetation restoration, through December 31. The pos- and two items related to native session limit will continue at and non-native oyster restoration two striped bass per person. The VQL and YMCA deliver on fi eld of promise projects. minimum size limit remains at The commission also adopted 18 inches. by Robb Hoff new restrictions on recreational Anglers will be allowed to KILMARNOCK—Vir- striped bass fi shing and post- possess two striped bass 18 ginia Quality Life chairman poned action on changes to com- inches to 28 inches total length, Douglas Monroe harkened mercial striped bass regulations or one striped bass 18 inches to back to 1998 when then U.S. until its September 27 meeting. 28 inches total length and one Secretary of State Colin Among the habitat cases, striped bass 34 inches or greater Powell visited the site where the commission voted 7-0 to in total length. the VQL and Northern Neck approve a permit for applicant The major change in the 2005 Family YMCA one day William Newton to construct a fi shery concerns the “protected” hoped to transform a “fi eld 33-foot-long by 17-foot-wide slot limit, whereby it will be of promises” into a vibrant private, non-commercial, open- unlawful for any person to pos- community center teeming sided timber boathouse on sess striped bass between 28 with activity. -

In Due Course: 2015 Changes to Virginia’S Laws

“All laws enacted at a regular session, . excluding a general appropriation law, shall take effect on the first day of July following the adjournment of the session of the General Assembly at which it has been enacted.” Constitution of Virginia, Article IV, Section 13 In Due Course: 2015 Changes to Virginia’s Laws In Due Course is a selection of legislation passed by the 2015 Session of the General Assembly that isVirginia likely to affect Division the daily of lives Legislative of the citizens Services of Virginia. The following legislation has been signed by the Governor and for the most part will go into effect on July 1, 2015. The summaries were prepared by the staff of the Division of Legislative Services. Complete information on actions of the 2015 Session is available on the Legislative Information System (http://lis.virginia.gov). Topics Agriculture Criminal Offenses/Procedure Pet Sales Alcoholic Beverage Control Education Science and Technology Boating Elections/Voting Social Services Business and Employment General Laws Special License Plates Campus Safety Health Taxation Civil Law Hunting, Trapping, and Fishing Tobacco Products Coalbed Methane Gas Licenses Transportation Constitutional Amendments Motor Vehicles/DMV Water Wells Agriculture HB 1277/SB 955. Industrial hemp production and manufacturing. The law allows the cultivation of industrial hemp by licensed growers as part of a university-managed research program. The law defines industrial hemp as the plant Cannabis sativa with a concentration of THC no greater than that allowed by federal law, excludes industrial hemp from the definition of marijuana in the Drug Control Act, and bars the prosecution of a licensed grower under drug laws for the possession of industrial hemp as part of the research program. -

Circuit Court Clerks' Duties List

CIRCUIT COURT CLERKS’ DUTIES LIST 2011 EDITION SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY _____________________________________________________________________________________________ CIRCUIT COURT CLERKS’ DUTIES LIST i TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I. CLERK’S OFFICE ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 A. FEES, COLLECTIONS AND COMPENSATION – GENERALLY ................................................................. 1 B. FINANCIAL REPORTS ..................................................................................................................................... 1 C. HANDLING FUNDS ......................................................................................................................................... 1 D. COMPENSATION - SALARY SYSTEM .......................................................................................................... 2 E. COMPENSATION - FEE SYSTEM ................................................................................................................... 3 F. EXCESS FUNDS ................................................................................................................................................ 4 G. EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES ......................................................................................................................... 4 H. EMPLOYMENT MATTERS ............................................................................................................................. 4 I. LEGAL ASSISTANCE ..................................................................................................................................... -

Draft Legislative Agenda General Assembly 2021 Session

DRAFT LEGISLATIVE AGENDA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 2021 SESSION September 18, 2020 CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – CITY COUNCIL Mayor Robert M. “Bobby” Dyer – At Large Vice-Mayor James L. Wood – Lynnhaven Jessica P. Abbott – Kempsville Michael Berlucchi – Rose Hall Barbara M. Henley – Princess Anne Louis R. Jones – Bayside John D. Moss – At Large Aaron R. Rouse – At Large Guy K. Tower - Beach Rosemary A. Wilson – At Large Sabrina D. Wooten – Centerville CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – GENERAL ASSEMBLY DELEGATION Senator Lynwood W. Lewis, Jr. – Senate District 6 Senator Jen A. Kiggans – Senate District 7 Senator William R. DeSteph, Jr. – Senate District 8 Senator John A. Cosgrove, Jr. – Senate District 14 Delegate Kelly K. Convirs-Fowler – House District 21 Delegate C. E. “Cliff” Hayes, Jr. – House District 77 Delegate Barry D. Knight – House District 81 Delegate Jason R. Miyares – House District 82 Delegate Nancy D. Guy – House District 83 Delegate Glenn R. Davis – House District 84 Delegate Alex Q. Askew – House District 85 Delegate Joseph C. Lindsey – House District 90 Delegate Robert S. Bloxom, Jr. – House District 100 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – CITY COUNCIL ................................................................................................. ii CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – GENERAL ASSEMBLY DELEGATION .......................................................... ii SECTION 1.1 – CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH LONG TERM POLICY POSITIONS 1. COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA COMMUNICATIONS TAX UPDATE5 ....................................5 SPONSORED BY CITY COUNCIL 2. FULL FUNDING FOR THE STEP-VA PROGRAM6............................................................................6 SPONSORED BY COUNCILMEMBER MICHAEL BERLUCCHI & THE VIRGINIA BEACH HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SECTION 1.2 – CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH NEW INITIATIVES 3. HEART DISEASE PRESUMPTION FOR SALARIED EMS PERSONNEL ........................................9 SPONSORED BY VICE-MAYOR JIM WOOD 4. -

VMRC Law Enforce Bro 3

Virginia Marine Resources Commission VIRGINIA MARINE POLICE Protecting our: A Career in Marine Law Enforcement FISHERY SPECIES may be open to you. MARINE HABITAT HOMELAND SECURITY Police work on the water is vital to the Commonwealth. Marine Police Officers must meet the same qualifications as other law enforcement personnel in Virginia. Additionally, they must demonstrate the ability to handle various watercrafts. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission is an equal opportunity employer. Minority citizens are strongly encouraged to apply. Interested persons should contact the: Virginia Marine Resources THE VIRGINIA MARINE POLICE Commission Department of Human Resources “Safeguards and Preserves the Marine Resources of the Commonwealth” 2600 Washington Avenue, Third Floor Newport News, Virginia 23607 ince the years following the Civil War, enforce- The men and women of the Virginia Marine Police ment officials have been working on the waters are responsible for the enforcement of commercial Ssafeguarding fishermen, marine habitat and the and recreational fishery laws and regulations. general welfare of Virginia’s citizens. The Virginia Officers also work in search and rescue operations, Marine Police—the current embodiment of that secu- enforce boating safety laws, respond to emergency rity—now patrol by sea, air and land to cover over calls, investigate boating accidents and criminal 5,000 miles of shoreline along the Chesapeake Bay, activity and provide counter-terrorism patrols to Photography by Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Jones III, VMRC its tributaries and the Atlantic Ocean. Cover and large boat photographs by Captain Andy Engemann, Virginia Port Authority our military installations, shipyards and nuclear Design by Donna Doyle, Virginia Office of Graphic Communications. -

Vbgov.Com :: City of Virginia Beach

DRAFT LEGISLATIVE AGENDA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 2021 SESSION September 4, 2020 CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – CITY COUNCIL Mayor Robert M. “Bobby” Dyer – At Large Vice-Mayor James L. Wood – Lynnhaven Jessica P. Abbott – Kempsville Michael Berlucchi – Rose Hall Barbara M. Henley – Princess Anne Louis R. Jones – Bayside John D. Moss – At Large Aaron R. Rouse – At Large Guy K. Tower - Beach Rosemary A. Wilson – At Large Sabrina D. Wooten – Centerville CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – GENERAL ASSEMBLY DELEGATION Senator Lynwood W. Lewis, Jr. – Senate District 6 Senator Jen A. Kiggans – Senate District 7 Senator William R. DeSteph, Jr. – Senate District 8 Senator John A. Cosgrove, Jr. – Senate District 14 Delegate Kelly K. Convirs-Fowler – House District 21 Delegate C. E. “Cliff” Hayes, Jr. – House District 77 Delegate Barry D. Knight – House District 81 Delegate Jason R. Miyares – House District 82 Delegate Nancy D. Guy – House District 83 Delegate Glenn R. Davis – House District 84 Delegate Alex Q. Askew – House District 85 Delegate Joseph C. Lindsey – House District 90 Delegate Robert S. Bloxom, Jr. – House District 100 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – CITY COUNCIL ................................................................................................. ii CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH – GENERAL ASSEMBLY DELEGATION .......................................................... ii SECTION 1.1 – CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH LONG TERM POLICY POSITIONS 1. CERTIFICATE OF PUBLIC NEED ........................................................................................................5 SPONSORED BY CITY COUNCIL 2. COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA COMMUNICATIONS TAX UPDATE ......................................6 SPONSORED BY CITY COUNCIL 3. FULL FUNDING FOR THE STEP-VA PROGRAM..............................................................................7 SPONSORED BY COUNCILMEMBER MICHAEL BERLUCCHI & THE VIRGINIA BEACH HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SECTION 1.2 – CITY OF VIRGINIA BEACH NEW INITIATIVES 4. HEART DISEASE PRESUMPTION FOR SALARIED EMS PERSONNEL .................................... -

Summary of 2012 Session

Virginia General Assembly 2012 Session Summary Virginia Division of Legislative Services Virginia General Assembly 2012 Session Summary Virginia Division of Legislative Services Published by the Division of Legislative Services Robert Tavenner, Director The summaries in this publication were prepared by the attorneys and research associates of the Virginia Division of Legislative Services. Business and Jurisprudence William Crammé, Section Manager Jescey French, Senior Attorney and Deputy Director Robie Ingram, Senior Attorney David Cotter, Senior Attorney Franklin Munyan, Senior Attorney Wenzel Cummings, Attorney Kristen Walsh, Attorney Mary Kate Felch, Senior Research Associate Finance and Government John Garka, Section Manager Jeffrey Sharp, Senior Attorney Nicole Brenner, Attorney Mark Vucci, Senior Attorney Maria J.K. Everett, Senior Attorney Amigo Wade, Senior Attorney Martin Farber, Senior Research Associate Lisa Wallmeyer, Senior Attorney Scott Meacham, Attorney Alan Wambold, Senior Research Associate David Rosenberg, Senior Attorney Rules, Education, Elections, and Special Projects R.J. (Jack) Austin, Section Manager Ellen Porter, Senior Attorney Jessica Eades, Senior Attorney Mary Spain, Senior Attorney Brenda Edwards, Senior Research Associate Sarah Stanton, Senior Attorney Cheryl Jackson, Manager, Information Services Thomas Stevens, Attorney Elizabeth Palen, Executive Director, Virginia Housing Commission The Virginia Division of Legislative Services acknowledges with gratitude the contribu- tions of Stephanie Kerns and Mindy Tanner to the preparation of this volume. Thanks also to DLS staff members Brenda Dickerson, Gwen Foley, Iris Fuentes, Darlene Jordan, Lilli Hausenfluck, and Viqi Wagner for staff support and editing. Thanks to DLAS staff mem- bers Larry Garton and Barbara Timberlake, who contributed important technical expertise. © 2012 by the Virginia Division of Legislative Services. Contents Introduction. -

Download Entire Virginia Saltwater Angler's Guide

VIRGINIA SALTWATER ANGLER’S GUIDE VIRGINIA SALTWATER ANGLER’S GUIDE The Virginia Saltwater Angler’s Guide was prepared by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. Funding was provided by saltwater recreational fishing license fees. Cover artwork by Alicia Slouffman. Back Cover artwork by Terre Ittner. Fish illustrations by Duane Raver. Graphic design by the DGS, Office of Graphic Communications. Welcome to the Virginia Angler’s Guide, a free publication of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to help recre- ational saltwater anglers become better fishermen and to encourage responsible stewardship of our natural resources. Here you will learn what you can catch, as well as where and when to catch it. Here you will find useful angling tips and help identifying that mysterious fish you pulled in. We’ll also show you where to find pub- WHITE MARLIN lic boat launches, and give the locations of our man-made reefs. They’re fish magnets! If you land an exceptional fish of a par- ticular species, you may be eligible for a plaque through our Saltwater Fishing Tournament. We’ll tell you who to contact about that. Virginia has some of the world’s best TABLE OF CONTENTS fishing in the mighty Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries as well as in the ocean off our beautiful shores. Some record-setting Virginia’s Marine Waters and Fisheries ..................... 1 fish have been caught in Virginia waters in recent years, including bluefin tuna, A Guide to Virginia’s Saltwater Fish ....................... 10 striped bass, king mackerel and croaker. How, When and Where to Catch The biggest fish are yet to be caught.