Caste-Based Oppression and the Class Struggle TU Senan CWI-India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Th ACT Accelerator Facilitation Council Meeting Livestreamed Virtual Meeting, 12 May 2021, 12:30 – 15:00 (CEST)

11 May 2021 6th ACT Accelerator Facilitation Council meeting Livestreamed virtual meeting, 12 May 2021, 12:30 – 15:00 (CEST) Co-hosts: Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General, WHO & Ms Stella Kyriakides, Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, European Commission Co-Chairs: Dr Zweli Mkhize, Minister of Health, South Africa & Mr Dag-Inge Ulstein, Minister of International Development, Norway Primary Objectives • Identify barriers and strategies for increasing uptake and use of COVID-19 tools at country level • Guide COVAX Task Force on strategies to expand COVID-19 vaccine production Draft Provisional Agenda Opening (10 min) 12h30 – Welcome • Co-Chairs & Co-Hosts opening remarks (10 12h40 min) Scale up of vaccine supply to COVAX (1hr 5 min), Chair: South Africa 12h40 – Objective: Guide COVAX Task Force on • Facilitator: Dr Ayoade Olatunbosun-Alakija 13h45 strategies to expand COVID-19 Vaccine • Presentation from Task Force (5 min) production • Interactive Panel (20 min) o Dr Amadou Sall, Director, Institut Pasteur, Senegal o Dr Patrick Soon Shiong, Chairman of the Chan Soon-Shiong Family Foundation, CEO & Chairman ImmunityBio & NantHealth o Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director General, WTO • Council Discussion (33 min) • Task Force comments in response to discussion (5 min) • Chair’s closing remarks (2 min) Health Systems Connector: Facilitating uptake & delivery of COVID-19 tools (60 min), Chair: Norway 13h45 – Objective: Identify barriers and strategies for • Facilitator: Emma Ross 14h45 increasing uptake and use of COVID-19 tools at • Interactive panel (20 min) country level o Dr Faisal Sultan, Special Assistant to Prime Minister on Health, Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination, Pakistan o Dr W. -

News Covering in the Online Press Media During the ANC Elective Conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107

News covering in the online press media during the ANC elective conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at Centre for Communication, Media and Society in the School of Applied Human Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Supervisor: Professor Donal McCracken 2019 As the candidate's supervisor, I agree with the submission of this thesis. …………………………………………… Professor Donal McCracken i Declaration - plagiarism I, ……………………………………….………………………., declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons' data, pictures, graphs or other information unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written, but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and the References sections. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… ii Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to the discipline of CCMS at Howard College, UKZN, led by Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli. It was the discipline’s commitment to academic research and academic excellence that attracted me to pursue this degree at CCMS (a choice that I don’t regret). -

Ending Covid Means Ending Aids, and Ending Both Means E

Ending Covid means ending Aids, and ending both means e... MAVERICK CITIZEN: EDITORIAL Ending Covid means ending Aids, and ending both means ending inequality By Mark Heywood • 14 June 2021 Faceboo Twitter Print Email AddThis 17 Ending Covid means ending Aids and ending both means ending inequality. (Photo: forbes.… When it comes to communicable diseases, the lesson we should take from Covid-19 is that one person is all it takes to start a devastating pandemic. Is that fact enough of a wake-up for governments to seriously tackle the social and economic determinants of health and disease? https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-06-14-ending-covid-means-ending-aids-and-ending-both-means-ending-inequality/[2021/06/15 1:25:12 PM] Ending Covid means ending Aids, and ending both means e... Last week, at the opening of the tenth South African Aids Conference, X Professor Salim Abdool Karim made a plenary presentation titled “HIV and Covid-19 in South Africa”. It revealed how interdependent the HIV/Aids and Covid-19 pandemics are becoming. Professor Salim Abdool Karim. (Photo: Dean Demos) In an overview, “SARS-CoV-2 infection in people living with HIV”, Karim referred to the case of a patient whose immune system was almost entirely suppressed because of HIV and who, as a result, experienced an acute Covid-19 infection that persisted over six months. Eventually, when she was put on to a new and effective regimen of antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) her immune system rebounded and she also recovered quickly from Covid-19. This was the good news. -

Covid-19: South Africa Pauses Use of Oxford Vaccine After

NEWS BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n372 on 8 February 2021. Downloaded from The BMJ Cite this as: BMJ 2021;372:n372 Covid-19: South Africa pauses use of Oxford vaccine after study casts http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n372 doubt on efficacy against variant Published: 08 February 2021 Elisabeth Mahase Rollout of the Oxford-AstraZeneca covid-19 vaccine is going to be hard to estimate. Without seeing results in South Africa has been paused after a study in 2000 in detail it isn’t possible to be sure how firm these healthy and young volunteers reported that it did not conclusions are. protect against mild and moderate disease caused by “However, if the press reports are correct it does seem the new variant (501Y.V2) that emerged there. of concern that protection against disease was not The study, which has not been published and was shown. The findings of the Novavax vaccine trial of seen by the Financial Times,1 looked at the efficacy 60% efficacy in the prevention of disease of any of the vaccine against the 501Y.V2 variant—which severity in HIV negative volunteers in South Africa accounts for around 90% of cases in South Africa—in might also suggest that vaccines will need to be HIV negative people. While reports suggested that updated in line with emerging mutations of the the vaccine was ineffective at preventing mild to virus.” moderate disease in that population, no data have 1 Mancini DP, Kuchler H, Pilling D, Cookson C, Cotterill J. Oxford/AstraZeneca been made available to the public. -

Cabinet Factsheet [PDF]

Cabinet held its scheduled virtual Meeting on Wednesday, 10 June 2020 1. CABINET DECISIONS On 31 December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a cluster of pneumonia cases in Update on Coronavirus Wuhan City, China. ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2’ (SARS-CoV-2) was confirmed commissioned within the (COVID-19) as the causative agent of what we now know as ‘Coronavirus Disease 2019’ (COVID-19). Since then, context of the Resistance Cabinet held itsthe scheduled virus has spread to more virtual than 100 countries, Meeting including South onAfrica. Wednesday, 10 June 2020 ● Cabinet receivedCabinet an updated held its virtual Meeting on Wednesday, 24 June and2020 Liberation Heritage report from the National Route (RLHR) Project. The CoronavirusOn Wednesday, Command Council 21 AprilCOVID-19 2021 is , anCabinet infectious held disease its thatfirst is physical spread, meetingRLHR sincecontributes the towards CABINET1.introduction(NCCC). CABINET DECISIONS DECISIONSof the national lockdowndirectly or indirectly, in 2020. from oneThis person is part to another. of Cabinet transitioningthe development and itself The NCCC tabled a number of transformation of the South ● Infection: recommendations pertainingto the new normal as the countryto drive the multidisciplinary continues gov- to reopen itself.African heritage landscape. On 31 December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a cluster of pneumonia cases in to the enhanced risk adjusted An infected person can spread the virusernment to a healthy interventions. person through: However, Update on Coronavirus Wuhan City, China. ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2’ (SARS-CoV-2) was confirmed commissioned within the the eye, nose and mouth or through droplets produced on coughing or sneezing. -

TO: Mr. Peter Sands, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization Dr. Ca

TO: Mr. Peter Sands, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization Dr. Catharina Boehme, World Health Organization Dr. Sergio Carmona, FIND Dr. Philippe Duneton, Unitaid Mr. Ira Magaziner, CHAI Ms. Etleva Kadilli, UNICEF Dr. OlusoJi Adeyi, World BanK Ms. Adriana Costa, World BanK Dr. Emilio Emini, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Dr. John NKengasong, Africa CDC Dr. BenJamin DJoudalbaye, African Union Mr. Nqobile Ndlovu, African Society for Laboratory Medicine Honorable Zweli Mkhize, National Department of Health, South Africa Honorable Rajesh Bhushan, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India Honorable Eduardo Pazuello, Ministry of Health, Brazil Honorable Mutahi Kagwe, Ministry of Health, Kenya Mr. Balram Bhargava, Indian Council of Medical Research Dr. Jarbas Barbosa, PAHO Ms. Gloria D. Steele, USAID Global Fund Members of the Board Unitaid Members of the Board ACT-A Facilitation Council Members ACT-A Diagnostics Pillar and Diagnostics Consortium Members Integrated Diagnostics Consortium Members CC: Mr. Warren C. Kocmond, President and Chief Operating Officer, Cepheid Mr. Philippe Jacon, President, Global Access, Cepheid 1 April 2021 Dear Colleagues, On 25 February 2021, 108 civil society organizations sent an open letter to Cepheid requesting that the company increase access to Xpert SARS-CoV-2 tests in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by committing a greater proportion of Cepheid’s manufacturing capacity to LMICs and by lowering the prices of Xpert tests for SARS-CoV-2 -

HWPL-KAASH FOUNDATION Content the 1ST RELIGIOUS YOUTH PEACE CAMP St • HWPL-KAASH Foundation- the 1 1 Religious Youth Peace Camp

HWPL-KAASH FOUNDATION Content THE 1ST RELIGIOUS YOUTH PEACE CAMP St • HWPL-KAASH Foundation- The 1 1 Religious Youth Peace Camp • 2nd International Faculty Development Program On Pedagogy Of Teaching 2 History • 3rd International Faculty Development Program On Emerging Approaches 6 And Trends In English Language And Literature th • 8 International Webinar On ‘Start-Ups 27 In India: Current Scenario’ • From the Editor's Desk | From the 29 Founder's Desk • Wellness Of Mind, Body And Women's 30 Health • Holistic Healthcare For Happiness 32 • Breastfeeding essentials 33 • 11th International Health Conference On 'Exploring The Application Of 34 Naturopathy And Ayurveda In Human Healthcare’ • Kaash Creative Corner 36 • Upcoming Events 38 • Birthdays 39 "Sir, first of all we congratulate to you and your energetic team for KAASH KONNECT. Your conducting so many activities for the betterment of community. These type of efforts really needed for the development of Indians. I personally like, your doing the documentation of these activities through the Kaash Konnect. It will be really helpful to our next generation. My best wishes to your sincere work." Ashok Pandurang Ghule Assistant Registrar Mumbai University Page 2 Issue No. 3: July - September 2020 KAASH Konnect INTERNATIONAL FACULTY DEVELOPMENT nd PROGRAM ON PEDAGOGY OF TEACHING HISTORY 2 by Pamela Dhonde A Teacher affects eternity, he can never tell organised its 2nd International Faculty where his influence stops. Development Program on Pedagogy of Teaching History. Held in collaboration - Henry Brooks Adams with St. Xavier’s Institute of Education, Mumbai and endorsed by the University of he above lines by Henry Brooks Ottawa, Canada, the International Faculty Adams, an American Historian, Development Program spanned across spells out the vital role that a seven days i.e. -

12DLTDC COL 04R1.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C 4 LEISURE DELHI TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA MONDAY 12 MAY 2003 DAILY CROSSWORD BELIEVE IT OR NOT TELEVISION tvguide.indiatimes.com CINEMA DD I 1400 Kutumb 1300 Hit Machine Hindi LIVE ENGLISH FILMS p.m.), Priya (2.25 & 7.45 p.m.), Satyam C’plexes BOL TARA BOL (5 p.m. Only) 0902 Series 1430 Dhadkan 1330 Zabardast Hits 2205 Aus Tour of WI 03: WI TEARS OF THE SUN (A): (Bruce Willis, Monica Shelly von Strunkel 1500 Ghar Ek Mandir 1400 Back To Back vs. Aus, 4th Test, Day Bellucci) 3 C’s (12.15 & 10.15 p.m.), DT Cinemas HINDI FILMS 0930 India Invented: Holi- (11.45 a.m., 5.25 & 10.25 p.m.), PVR Saket (3.35 1530 Alpviram 1430 Zabardast Hits 4, Session 2&3 LIVE ISHQ VISHQ: (Shahid, Amrita, Shenaz) Delite, day Spl. for Children & 11.30 p.m.), PVR Vikaspuri (11 a.m. & 8.15 ARIES (March 21 - April 19) Irritating as various 1600 Kaun Apna Kaun 1500 Back to Back Chanakya (12.30 & 3.30 p.m.), DT Cinemas (12 1000 News in Sanskrit p.m.), PVR Naraina (11.45 a.m., 5.15 & 10.45 disputes are, you’d be well advised at least to lis- Paraya 1530 Hit Machine NEWS noon, 2.40, 5.25, 7.45 & 10.30 p.m.), Rachna, PVR 1005 India Invented: p.m.), Priya (11.50 a.m., 4.55 & ten to what others have to say. While it’s true that 1630 Malgudi Days 1600 Hotline Saket (11.30 a.m., 2.15, 5, 7.45 & 10.30 p.m.), Holiday Spl. -

No. SONG TITLE MOVIE/ALBUM SINGER 20001 AA AA BHI JA

No. SONG TITLE MOVIE/ALBUM SINGER 20001 AA AA BHI JA TEESRI KASAM LATA MANGESHKAR 20002 AA AB LAUT CHALE JIS DESH MEIN GANGA BEHTI HAI MUKESH, LATA 20003 AA CHAL KE TUJHE DOOR GAGAN KI CHHAON MEIN KISHOE KUMAR 20004 AA DIL SE DIL MILA LE NAVRANG ASHA BHOSLE 20005 AA GALE LAG JA APRIL FOOL MOHD. RAFI 20006 AA JAANEJAAN INTEQAM LATA MANGESHKAR 20007 AA JAO TADAPTE HAI AAWAARA LATA MANGESHKAR 20008 AA MERE HUMJOLI AA JEENE KI RAAH LATA, MOHD. RAFI 20009 AA MERI JAAN CHANDNI LATA MANGESHKAR 20010 AADAMI ZINDAGI VISHWATMA MOHD. AZIZ 20011 AADHA HAI CHANDRAMA NAVRANG MAHENDRA & ASHA BHOSLE 20012 AADMI MUSAFIR HAI APNAPAN LATA, MOHD. RAFI 20013 AAGE BHI JAANE NA TU WAQT ASHA BHOSLE 20014 AAH KO CHAHIYE MIRZA GAALIB JAGJEET SINGH 20015 AAHA AYEE MILAN KI BELA AYEE MILAN KI BELA ASHA, MOHD. RAFI 20016 AAI AAI YA SOOKU SOOKU JUNGLEE MOHD. RAFI 20017 AAINA BATA KAISE MOHABBAT SONU NIGAM, VINOD 20018 AAJ HAI DO OCTOBER KA DIN PARIVAR LATA MANGESHKAR 20019 AAJ KAL PAANV ZAMEEN PAR GHAR LATA MANGESHKAR 20020 AAJ KI RAAT PIYA BAAZI GEETA DUTT 20021 AAJ KI SHAAM TAWAIF ASHA BHOSLE 20022 AAJ MADAHOSH HUA JAAYE RE SHARMILEE LATA, KISHORE 20023 AAJ MAIN JAWAAN HO GAYI HOON MAIN SUNDAR HOON LATA MANGESHKAR 20024 AAJ MAUSAM BADA BEIMAAN HAI LOAFER MOHD. RAFI 20025 AAJ MERE MAAN MAIN SAKHI AAN LATA MANGESHKAR 20026 AAJ MERE YAAR KI SHAADI HAI AADMI SADAK KA MOHD.RAFI 20027 AAJ NA CHHODENGE KATI PATANG KISHORE KUMAR, LATA 20028 AAJ PHIR JEENE KI GUIDE LATA MANGESHKAR 20029 AAJ PURANI RAAHON SE AADMI MOHD. -

Antisemitism in the UK

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Antisemitism in the UK Tenth Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 October 2016 HC 136 Published on 16 October 2016 by authority of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership James Berry MP (Conservative, Kingston and Surbiton) Mr David Burrowes MP (Conservative, Enfield, Southgate) Nusrat Ghani MP (Conservative, Wealden) Mr Ranil Jayawardena MP (Conservative, North East Hampshire) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) (Interim Chair) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Naz Shah MP (Labour, Bradford West) Mr Chuka Umunna MP (Labour, Streatham) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) [Victoria Atkins has been appointed to a Government post and is taking no further part in Committee activities. She will be formally discharged from the Committee by a Motion of the House, and a replacement appointed, in due course] The following were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Keir Starmer MP (Labour, Holborn and St Pancras) Anna Turley MP (Labour (Co-op), Redcar) Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. -

Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Song Download Pagalworld

Haal e dil tujhko sunata song download pagalworld CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Description. renuzap.podarokideal.ru muder 2 download mp3 n video link renuzap.podarokideal.ru Watch the complete video song 'Haal e dil tujhko sunata' of movie Murder 2 . list of Haal E Dil (), Download Hale Dil Tujhko Sunata Murder 2 Full Song Emraan Hashmi mp3 for free. Haal E Dil ( MB) song and listen to Haal E Dil popular song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 09/05/ · Hale Dil Lyrics & pdf – Harshit Saxena – Murder 2. The Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Lyrics from Emraan Hashmi and Jacqueline Fernandes’s Movie Murder 2. If there are any mistakes in the Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Lyrics, kindly post below in the comments section, we will rectify it . Hale Dil Tujhko Sunata Cover Download In 64 KBPS - mb Download In KBPS - mb Download In KBPS - mb Download In KBPS - mb Previous Track» Aankhon Mein Aansoon New Cover Mp3 Song Next Track» Network New Punjabi Cover Mp3 Song. The Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Lyrics from Emraan Hashmi and Jacqueline Fernandes’s Movie Murder 2. If there are any mistakes in the Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Lyrics, kindly post below in the comments section, we will rectify it as soon as possible.. Mahesh Bhatt’s Vishesh Films Banner presents Murder 2 is Directed by Mohit Suri. Haal E Dil Tujhko Sunata Music been composed by Harshit Saxena. 30/05/ · Hale Dil MP3 Song by Harshit Saxena from the movie Murder 2. Download Hale Dil (हाले िदल) song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Murder 2 Hale Dil song offline. -

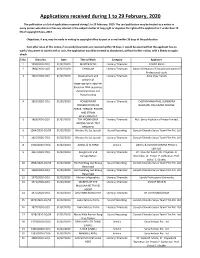

Applications Received During 1 to 29 February, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 29 February, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 29 February, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 1959/2020-CO/L 01/02/2020 MASTER SCAN Literary/ Dramatic FAHAD KHAN 2 1960/2020-CO/L 01/02/2020 Certificate Literary/ Dramatic Swami Vivekanand Educational Council of Professional study 3 1961/2020-CO/L 01/02/2020 Development and Literary/ Dramatic Asha Vijay Durafe analysis of steganographic algoritm based on DNA sequence, dynamical chaos and fractal coding 4 1962/2020-CO/L 01/02/2020 POWERPOINT Literary/ Dramatic CHETAN MAHATME, SURENDRA PRESENTATION ON NAGPURE, RAJKUMAR CHADGE FORCE, TORQUE, POWER AND STRAIN MEASUREMENT 5 1963/2020-CO/L 01/02/2020 THE WORKHORSE Literary/ Dramatic M/s. Servo Hydraulics Private Limited, AMONG VALVE TEST BENCHES! 6 1964/2020-CO/SR 01/02/2020 Bhataru Ke Sut Jayeda Sound Recording Ganesh Chandra Surya Team Film Pvt.