Inscriptions from Hadrianopolis, Tieion, Iulia Gordos and Toriaion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Faraone Ancient Greek Love Magic.Pdf

Ancient Greek Love Magic Ancient Greek Love Magic Christopher A. Faraone Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second printing, 2001 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2001 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Faraone, Christopher A. Ancient Greek love magic / Christopher A. Faraone. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-674-03320-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-00696-8 (pbk.) 1. Magic, Greek. 2. Love—Miscellanea—History. I. Title. BF1591.F37 1999 133.4Ј42Ј0938—dc21 99-10676 For Susan sê gfir Ãn seautá tfi f©rmaka Æxeiv (Plutarch Moralia 141c) Contents Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Ubiquity of Love Magic 5 1.2 Definitions and a New Taxonomy 15 1.3 The Advantages of a Synchronic and Comparative Approach 30 2 Spells for Inducing Uncontrollable Passion (Ero%s) 41 2.1 If ErÃs Is a Disease, Then Erotic Magic Is a Curse 43 2.2 Jason’s Iunx and the Greek Tradition of Ago%ge% Spells 55 2.3 Apples for Atalanta and Pomegranates for Persephone 69 2.4 The Transitory Violence of Greek Weddings and Erotic Magic 78 3 Spells for Inducing Affection (Philia) 96 3.1 Aphrodite’s Kestos Himas and Other Amuletic Love Charms 97 3.2 Deianeira’s Mistake: The Confusion of Love Potions and Poisons 110 3.3 Narcotics and Knotted Cords: The Subversive Cast of Philia Magic 119 4 Some Final Thoughts on History, Gender, and Desire 132 4.1 From Aphrodite to the Restless -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses X Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods An international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity May 14-15, 2020 / Izmir, Turkey Edited by Ergün Laflı Izmir 2020 Last update: 04/05/2020. 1 Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods. Papers presented at the international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity, May 14-15, 2020 / Izmir, Turkey, Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea – Acta congressus communis omnium gentium Smyrnae. Copyright © 2020 Ergün Laflı (editor) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the editor. ISBN: 978-605-031-211-9. Page setting: Ergün Laflı (Izmir). Text corrections and revisions: Hugo Thoen (Deinze / Ghent). Papers, presented at the international video conference, entitled “Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods. An international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity” in May 14–15, 2020 in Izmir, Turkey. 36 papers with 61 pages and numerous colourful figures. All papers and key words are in English. 21 x 29,7 cm; paperback; 40 gr. quality paper. Frontispiece. A Roman stele with two portraits in the Museum of Kırşehir; accession nos. A.5.1.95a-b (photograph by E. -

Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC

European Journal of Archaeology 20 (1) 2017, 120–147 This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Story of a Forgotten Kingdom? Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC 1,2,3 1,3 CHRISTOPHER H. ROOSEVELT AND CHRISTINA LUKE 1Department of Archaeology and History of Art, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 2Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 3Department of Archaeology, Boston University, USA This article presents previously unknown archaeological evidence of a mid-second-millennium BC kingdom located in central western Anatolia. Discovered during the work of the Central Lydia Archaeological Survey in the Marmara Lake basin of the Gediz Valley in western Turkey, the material evidence appears to correlate well with text-based reconstructions of Late Bronze Age historical geog- raphy drawn from Hittite archives. One site in particular—Kaymakçı—stands out as a regional capital and the results of the systematic archaeological survey allow for an understanding of local settlement patterns, moving beyond traditional correlations between historical geography and capital sites alone. Comparison with contemporary sites in central western Anatolia, furthermore, identifies material com- monalities in site forms that may indicate a regional architectural tradition if not just influence from Hittite hegemony. Keywords: survey archaeology, Anatolia, Bronze Age, historical geography, Hittites, Seha River Land INTRODUCTION correlates of historical territories and king- doms have remained elusive. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

The Norton Introduction to Literature, Shorter

CRITICAL CONTEXTS: 26 SOPHOCLES’S ANTIGONE Even more than other forms of literature, drama has a relatively stable canon, a select group of plays that the theater community thinks of as especially worthy of frequent per for mance. New plays join this canon, of course, but theater com- panies worldwide tend to perform the same ones over and over, especially those by Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Sophocles. The reasons are many, involving the plays’ themes and continued appeal across times and cultures as well as their formal literary and theatrical features. But their repeated perfor mance means that a relatively small number of plays become much better known than all the others and that there is a tradition of “talk” about those plays. A lot of this talk is informal and local, resulting from the fact that people see plays communally, viewing per for mances together and often comparing responses afterward. But more permanent and more formal responses also exist; individual productions of plays are often reviewed in newspapers and magazines, on radio and tele vi sion, and on the Internet. Such reviews concentrate primarily on evaluating specifi c productions. But because every production of a play involves a partic u lar inter- pretation of the text, cumulative accounts of perfor mances add up to a body of interpretive criticism— that is, analytical commentary about many aspects of the play as text and as per formance. Scholars add to that body of criticism by publishing their own interpretations of a play in academic journals and books. Sophocles’s -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Continuity of Architectural Traditions in the Megaroid Buildings of Rural Anatolia: the Case of Highlands of Phrygia

ITU A|Z • Vol 12 No 3 • November 2015 • 227-247 Continuity of architectural traditions in the megaroid buildings of rural Anatolia: Te case of Highlands of Phrygia Alev ERARSLAN [email protected] • Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul Aydın University, Istanbul, Turkey Received: May 2015 Final Acceptance: October 2015 Abstract Rural architecture has grown over time, exhibiting continuities as well as ad- aptations to the diferent social and economic conditions of each period. Conti- nuity in rural architecture is related to time, tradition and materiality, involving structural, typological, functional and social issues that are subject to multiple interpretations. Tis feldwork was conducted in an area encompassing the villages of the dis- tricts of today’s Eskişehir Seyitgazi and Afyon İhsaniye districts, the part of the landscape known as the Highlands of Phrygia. Te purpose of the feldwork was to explore the traces of the tradition of “megaron type” buildings in the villages of this part of the Phrygian Valley with an eye to pointing out the “architectural con- tinuity” that can be identifed in the rural architecture of the region. Te meth- odology employed was to document the structures found in the villages using architectural measuring techniques and photography. Te buildings were exam- ined in terms of plan type, spatial organization, construction technique, materials and records evidencing the age of the structure. Te study will attempt to produce evidence of our postulation of architectural continuity in the historical megara of the region in an efort to shed some light on the region’s rural architecture. Te study results revealed megaroid structures that bear similarity to the plan archetypes, construction systems and building materials of historical megarons in the region of the Phrygian Highlands. -

Two Phrygian Gods Between Phrygia and Dacia1

Colloquium Anatolicum 2016 / 15 Keywords: Zeus Surgastes, Zeus Sarnendenos, gods, Phrygia, Galatia, Roman Dacia. Two Phrygian Gods Between Phrygia The author discusses the cult of Zeus Syrgastes (Syrgastos) and Zeus Sarnendenos and points out 1 and Dacia that both are of Phrygian uorigin. For Syrgastes evidence from Old Phrygian records must be added, which proves that this god was long established and had possibly Hittite-Luwian roots. Zeus Sarnendenos seems to be more recent and his mother-country may be sought in north-east Phrygia / north-west Galatia. Both cults were brought to Roman Dacia by colonists coming from Bithynia, possibly from the area of Tios/Hadrianopolis (for Zeus Syrgastes) and Galatia, perhaps from the area of modern-day Mihalıcçık (for Zeus Sarnendenos). Alexandru AVRAM2 Anahtar Kelimeler: Zeus Surgastes, Zeus Sarnendenos, Tanrılar, Phrygia, Galatia, Dacia. |70| Bu makalede Zeus Syrgastes (Syrgastos) and Zeus Sarnendenos kültleri ve bu kültlerin her iki- |71| sinin de Frigya kökenli oldukları tartışılmaktadır. Syrgastes ile ilgili kaynaklar arasında Eski Frig kaynakları bulunmaktadır ki bu durum bize bu tanrının kökenlerinin çok eskiye dayan- dığını, muhtemelen Hitit-Luwi kökenlerine sahip olduğunu göstermektedir. Zeus Sarnendenos daha genç bir tanrı olarak gözükmektedir ve anayurdu muhtemelen kuzey-doğu Frigya / ku- zey-batı Galatia olabilir. Muhtemelen her iki kült de Roma Dacia’sına bugünkü Bithynia’dan, Tios/Hadrianopolis (Zeus Syrgastes için) bölgesinden ve Galatia’dan, muhtemelen modern Mihalıcçık (Zeus Sarnendenos için) civarından gelen yerleşimcilerce getirilmiştir. 1 Hakeme Gönderilme Tarihi: 10.05.2016 ve 30.09.2016; Kabul Tarihi: 09.06.2016 ve 03.10.2016. 2 Alexandru AVRAM. Université du Maine, Faculté des Lettres, Langues et Sciences humaines, Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72000 Le Mans, France. -

Pecunia Omnes Vincit

PECUNIA OMNES VINCIT Pecunia Omnes Vincit COIN AS A MEDIUM OF EXCHANGE THROUGHOUT CENTURIES ConfErEnCE ProceedingS OF THE THIRD INTERNATIONAL numiSmatiC ConfErEnCE KraKow, 20-21 may 2016 Edited by Barbara Zając, Paulina Koczwara, Szymon Jellonek Krakow 2018 Editors Barbara Zając Paulina Koczwara Szymon Jellonek Scientific mentoring Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Reviewers Prof. Dr hab. Katarzyna Balbuza Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Dr Arkadiusz Dymowski Dr Kamil Kopij Dr Piotr Jaworski Dr Dariusz Niemiec Dr Krzysztof Jarzęcki Proofreading Editing Perfection DTP GroupMedia Project of cover design Adrian Gajda, photo a flan mould from archive Paphos Agora Project (www.paphos-agora.archeo.uj.edu.pl/); Bodzek J. New finds of moulds for cast- ing coin flans at the Paphos agora. In. M. Caccamo Caltabiano et al. (eds.), XV Inter- national Numismatic Congress Taormina 2015. Proceedings. Taormina 2017: 463-466. © Copyright by Adrian Gajda and Editors; photo Paphos Agora Project Funding by Financial support of the Foundation of the Students of the Jagiellonian University „BRATNIAK” © Copyright by Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Krakow 2018 ISBN: 978-83-939189-7-3 Address Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University 11 Gołębia Street 31-007 Krakow Contents Introduction /7 Paulina Koczwara Imitations of Massalian bronzes and circulation of small change in Pompeii /9 Antonino Crisà Reconsidering the Calvatone Hoard 1942: A numismatic case study of the Roman vicus of Bedriacum (Cremona, Italy) /18 Michał Gębczyński Propaganda of the animal depictions on Lydian and Greek coins /32 Szymon Jellonek The foundation scene on Roman colonial coins /60 Barbara Zając Who, why, and when? Pseudo-autonomous coins of Bithynia and Pontus dated to the beginning of the second century AD /75 Justyna Rosowska Real property transactions among citizens of Krakow in the fourteenth century: Some preliminary issues /92 Introduction We would like to present six articles by young researchers from Poland and Great Britain concerning particular aspects of numismatics. -

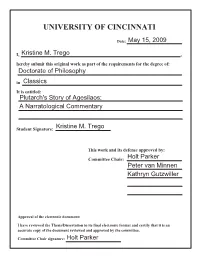

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do.