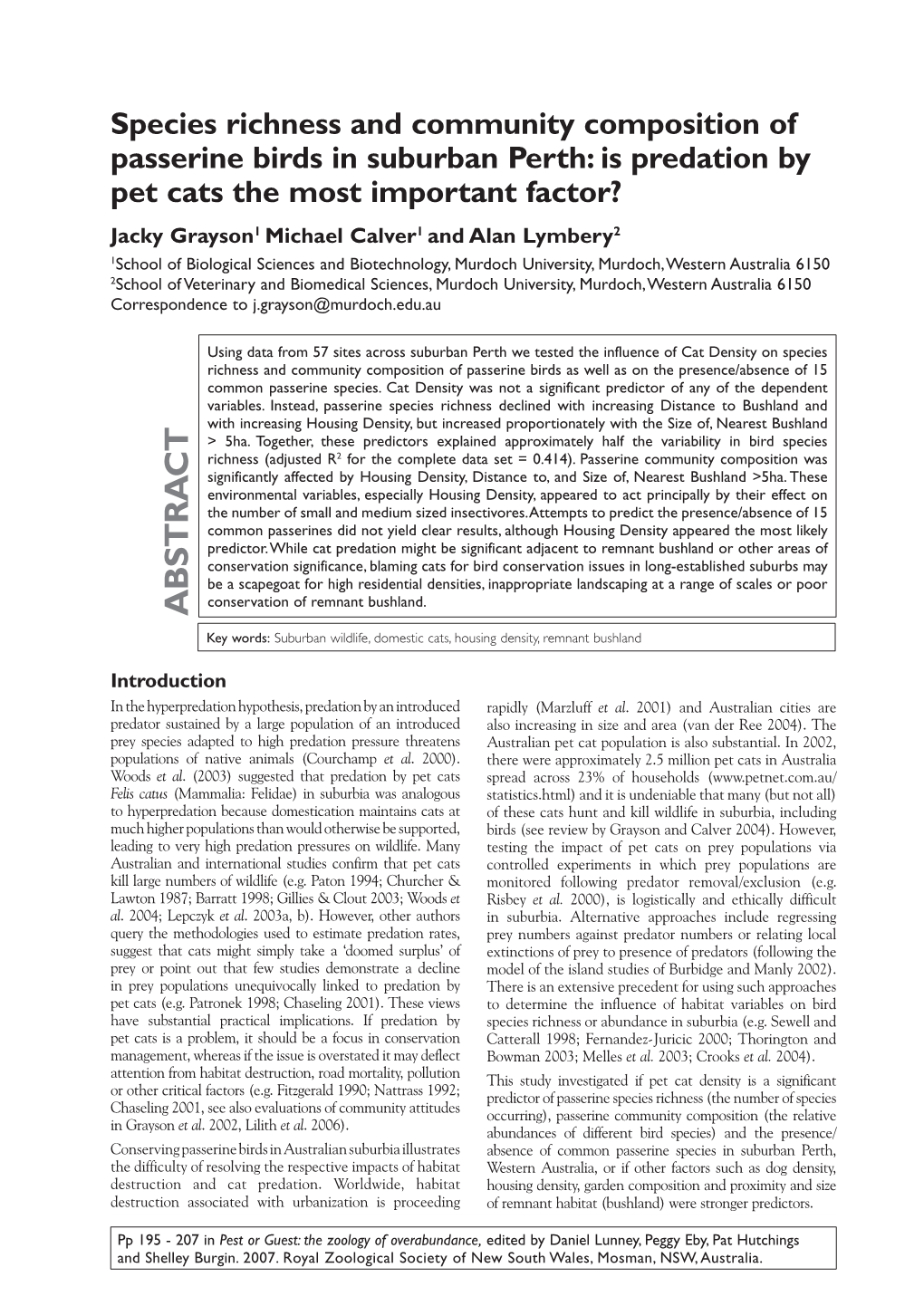

Species Richness and Community Composition of Passerine Birds In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Effectiveness of Native Nectar-Feeding Birds and the Introduced Apis Mellifera As Pollinators of the Kangaroo Paw, Anigozanthos

1 Effectiveness of native nectar-feeding birds and the introduced Apis mellifera as 2 pollinators of the kangaroo paw, Anigozanthos manglesii (Haemodoraceae) 3 Bronwyn M. Ayre1,2, *, David G. Roberts2,5, Ryan D. Phillips2,3,4, Stephen D. Hopper5, Siegfried L. Krauss1,2 4 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6009, Australia, 2Kings Park 5 Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Perth, WA 6005, Australia, 3Department of 6 Ecology, Environment and Evolution, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia, 4Ecology and 7 Evolution, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 8 and 5Centre for Excellence in Natural Resource Management, School of Agriculture and Environment, 9 University of Western Australia, Albany, WA 6330, Australia 10 Running title: Birds, bees and Kangaroo Paw pollination 11 Summary text (table of contents): Plants pollinated by vertebrates are often visited by native and 12 introduced insect species foraging for pollen and nectar, with potentially negative consequences for 13 plant fitness. European Honeybees are the most common visitor to the Red and Green Kangaroo Paw 14 but primarily steal nectar and pollen, with native nectar-feeding birds critical for high reproductive 15 success. For many plant species, the relative importance of bird-pollinators and exotic insect species 16 remains largely unknown. 1 17 Abstract: 18 Plants pollinated by vertebrates are often visited by native and exotic insects foraging for pollen and 19 nectar. We compared flower visitation rates, foraging behaviour, and the contribution to reproduction 20 of nectar-feeding birds and the introduced honeybee Apis mellifera in four populations of the bird- 21 pollinated Anigozanthos manglesii (Haemodoraceae). -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

Southern Gulf, Queensland

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

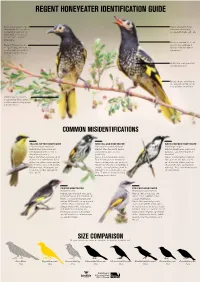

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Birdwatching Around Corrigin

SITES TO THE WEST INTRODUCTON: In the following woodland sites, look for Australian Agricultural and pastoral industries form the basis of BIRDWATCHING Ringneck, Red-capped Parrot, Rufous Whistler, Grey this thriving community. A visit to some of the places Shrike-thrush, Red-capped Robin, Southern Scrub- mentioned will help you to experience a wide range robin, Redthroat, Weebill, Striated Pardalote and of natural features, vegetation and bird life within the AROUND Brown-headed Honeyeater. shire and surrounding areas. From a bird-watching perspective, this is a good area to see raptors. CORRIGIN Please take care if you need to park on road verges to access 1. KUNJIN sites, especially in summer when the fire risk is greater. An old town site adjoins a nature reserve. Excellent woodlands ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: including Rock Sheoak, Kondinin Blackbutt and mallees. Illustrations: Judy Blyth, Alan Collins,, Keith Lightbody, Ron Johnstone, Susan Tingay, Eric Tan. Striated Pardalote Local information: Robin Campbell, BirdLife Avon & Birdata, 2. JUBUK NORTH ROAD Wendy Kenworthy. 20km west of Corrigin. Parkland with patches of York Gum woodland, heath and salt-land. Local contacts: Robin 0499 624 038 Lawry 0429 164 187 3. LOMOS Guide No. 20AB; Revised Nov 2017. All content is subject to A good patch of mixed open woodland. Red Morrells, copyright ©. Queries to BirdLife Western Australia. Silver Mallet, mallees and Wandoo support Rufous Treecreeper, Redthroat, Crimson Chat, Varied Sittella and Grey Currawong. 4. OVERHEU Rufous Whistler On Brookton Hwy, with Eucalyptus macrocarpa and sheoak. Best access is from a roadside bay on Brookton Nankeen Kestrel by David Free Highway. BirdLife Western Australia members are offered a variety of 5. -

Comparative Bathing Behavior in Some Australian Birds

J. Field Ornithol., 62(3):386-389 COMPARATIVE BATHING BEHAVIOR IN SOME AUSTRALIAN BIRDS N. A.M. VE•EEK Departmentof BiologicalSciences SimonFraser University Burnaby,British ColumbiaV5A IS6, Canada Abstract.--The bathingbehavior of Alcedinidae(2 species),Dicruridae (1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae (5) and Zosteropidae(1) is describedand compared with that of other species.The birds were observedfrom a blind while they bathed in a water hole with a sloping shore line and flanked on one side by shrubs.Two forms of bathing were noted: diving from shrubsand wading into shallow water. Although more data are needed,it is suggestedthat the bathing methodsused by birds differ at the generic level and not necessarilyat the family level. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DE LA CONDUCTA DE BAI•ARSE POR ALGUNAS AVES AUSTRALIANAS Sinopsis.--Sedescribe y comparala conductade bafiarsede Alcedinidae(2 especies),Di- cruridae(1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae(5) y Zosteropidae(1) con la de otras especies.Las avesse observarondesde escondijos mientras se bafiabanen un ojo de agua flanquedoen un lado pot arbustos.Se noratondos formas de bafiarse:tiffindose en clavado desdeun arbusto y andando o brincando desdela orilla hacia agua de poca pro- fundidad.Aunque se necesitanmils datos,sugiero que el m•todo de bafiarseutilizado pot las avesdifiere a nivel de g•nero y no necesariamentea nivel de familia. Although someforms of feather maintenancebehavior have been stud- ied in detail (e.g.,preening, Hatch et al. 1986, Ierseland Bol 1958) others (e.g., bathing) are rarely mentionedin the bird literature (Burtt 1983). As most feather maintenanceactivities occur infrequently and unpre- dictablyand are often of short duration, they are difficult to study sys- tematically.Simmons (1964) and Slessers(1970) reportedon the different bathing techniquesof birds and made the first attemptsto compareand interpret them in terms of morphologyand ecology.The observations here reported show that theseinterpretations may have to be modified. -

Birdwatching Around Bridgetown Greenbushes

1. Blackwood River Walk Birdwatching in Bridgetown-Greenbushes District An easy 3-4km return walk along the Blackwood Birdwatching River with seating to enjoy the quiet ambience and Bridgetown-Greenbushes District birdlife. Start at the car park at the River Park next The Bridgetown-Greenbushes Shire is a comfortable three hour drive (256km) south of Perth. Bridgetown is nestled to the main bridge and follow the boardwalk across around along the Blackwood River Valley and is surrounded by the river. Turn left for a shorter walk to a creekline attractive rural landscapes and healthy native Forest or right to walk to Gifford Rd and back among Conservation Areas and National Parks. Greenbushes sits Bridgetown Marri and Jarrah trees and views to the river with on the highest point in the area among native forests 15km Melaleuca thickets. Look for waterbirds along the north of Bridgetown. Both towns were settled early and river: Purple Swamphen, Eurasian Coot, Australasian have a long pioneering heritage. Greenbushes and Hoary-headed Grebes and cormorants. Along the track, Western Rosella, Red-capped and Elegant A brochure entitled ‘Your Guide to Walk Trails— Greenbushes-Bridgetown-Hester’ and other information are Parrots, Golden Whistler, Red- available from the Bridgetown Visitor Centre on Hampton eared Firetail, Red-winged and St (Ph: 08 9761 1740). The Greenbushes Discovery Centre Splendid Fairy-wrens, Fan-tailed also has information on the various walk trails around town Cuckoo, Striated Pardalote and (Ph: 08 9764 3883) sometimes Crested Shrike-tit can be found. Western Rosella Acknowledgements Support (male) by the Shire of 2. Rifle Range Rd Bridgetown-Greenbushes Drive about 3km south from the main bridge over the Blackwood River, then turn right into Rifle Range Illustrations / photographs Rd.