Community Wildfire Preparedness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valiano FIRE PROTECTION PLAN

August 4, 2015 Redline 8.28.2015 Revision; November 20, 2015 Revision; 12.16.2015 Revision Valiano FIRE PROTECTION PLAN TRACT TM 5575 RPL San Marcos Fire Department and Fire Protection District County of San Diego August 4, 2015August 28, 2015November 20, 2015December 16, 2015 Applicant: Integral Communities 2235 Encinitas Blvd, Suite 216 Encinitas, CA 92024 C. Douglas Pumphrey David C. Bacon,Ronald J. Woychak President Senior Wildland Fire Associate FIREWISE 2000, Inc. FIREWISE 2000, Inc. 26337 Sky Drive1320 Scenic Dr. 951-315-2030 Escondido, CA 920296 [email protected] Telephone: 760-745-3947 Fax: 760-557-2301 [email protected] Signed:______________________ Date:______________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ FIREWISE 2000, INC Page 1 of 87 Valiano Fire Protection Plan August 4, 2015 Redline 8.28.2015 Revision; November 20, 2015 Revision; 12.16.2015 Revision TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Project Location 7 1.2 Project Description 7 1.3 Community Overview 9 1.4 Environmental Setting 9 2.0 GUIDELINES FOR THE DETERMINATION OF SIGNIFICANCE 15 2.1 People and Structure Exposure to Fire 16 2.2 Fire Access 16 2.3 Water Supply 16 2.4 Ignition Resistant Construction and Fire Protection Systems 16 3.0 ANTICIPATED FIRE BEHAVIOR IN THE VICINITY 16 3.1 Fire Behavior Potential 16 3.2 On-Site Vegetation 17 3.3 Off-Site Vegetation 19 3.4 Wildland Fire Behavior Assessment 19 4.0 MITIGATION MEASURES AND DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 22 -

Rancho Santa Fe Fire Protection District Board of Directors Meeting Agenda

RANCHO SANTA FE FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING AGENDA Rancho Santa Fe FPD September 26, 2018 Board Room – 18027 Calle Ambiente 1:00 pm PT Rancho Santa Fe, California 92067 Special (in lieu or regular) Meeting RULES FOR ADDRESSING BOARD OF DIRECTORS Members of the audience who wish to address the Board of Directors are requested to complete a form near the entrance of the meeting room and submit it to the Board Clerk. Any person may address the Board on any item of Board business or Board concern. The Board cannot take action on any matter presented during Public Comment, but can refer it to the Administrative Officer for review and possible discussion at a future meeting. As permitted by State Law, the Board may take action on matters of an urgent nature or which require immediate attention. The maximum time allotted for each presentation is FIVE (5) MINUTES. Pledge of Allegiance 1. Roll Call 2. Motion waiving reading in full of all Resolutions/Ordinances 3. Public Comment All items listed on the Consent Calendar are considered routine and will be enacted by one motion without discussion unless Board Members, Staff or the public requests removal of an item for separate discussion and action. The Board of Directors has the option of considering items removed from the Consent Calendar immediately or under Unfinished Business. 4. Consent Calendar a. Board of Directors Minutes Board of Directors minutes of August 8, 2018 ACTION REQUESTED: Approve b. Receive and File i. Monthly/Quarterly Reports (1) List of Demands Check -

Fourth Quarter 2020

PIONEER HOOK AND LADDER FI REHOUSE MUSEUM 4th QUARTER | 2020 NOTES FROM BOX 2851 Assist ant Fire Chief Kevin Est er OFFICERS Business Operat ions Branch President San Diego (CA) Fire-Rescue Department Kevin McWalters SDFD Ret. Chief Est er started his fire Vice President service career in 1978, at Jack Gosney the age of 14,as a Fire DMFD Ret. Explorer with the Orange Secretary Jeff Williams County (CA) Fire Captain, SDFD Department. While in Treasurer Orange County, he Rob Harris obtained his Emergency National Tax Relief Medical Technician Museum Executive certificate, attended fire Director Mike Colafrancesco science curriculum at SDFD Station 11/C Santa Ana College, and Board Members worked as an OCFD Paid Bill Black Call Firefighter and Fire Safety Components Material Technician in their Dave Duea Service Center. Fire Etc. Kevin Ester He joined the San Diego SDFD Assistant Chief Fire-Rescue Department in John Fisher 1985. SDFD/Straight Days During his Emergency Operations career he has been assigned to Bob Hammond SDFD Ret. the busiest stations throughout the 373 square mile city, while Mark Morrison serving in the ranks of Firefighter to Battalion Chief. He also was SDFD Firefigher/L-145 Rep assigned to the technical rescue team for several years and served S t u a r t Sprung as one of the original members of Federal Emergency Management Cal Fire Division Chief Agencies? Urban Search & Rescue, California Task Force 8. While in Dale Wineteer the ranks, he spent 7 years on the Occupational Health & Safety Road One Towing Committee, working heavily on personal protective clothing issues, Newsletter and worked with the Logistics division on fire apparatus and light Michael Watson fleet specifications. -

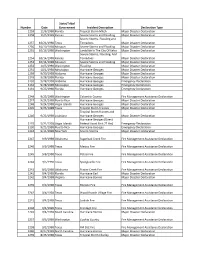

Identification of Disaster Code Declaration

State/Tribal Number Date Government Incident Description Declaration Type 1259 11/6/1998 Florida Tropical Storm Mitch Major Disaster Declaration 1258 11/5/1998 Kansas Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration Severe Storms, Flooding and 1257 10/21/1998 Texas Tornadoes Major Disaster Declaration 1256 10/19/1998 Missouri Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1255 10/16/1998 Washington Landslide In The City Of Kelso Major Disaster Declaration Severe Storms, Flooding, And 1254 10/14/1998 Kansas Tornadoes Major Disaster Declaration 1253 10/14/1998 Missouri Severe Storms and Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1252 10/5/1998 Washington Flooding Major Disaster Declaration 1251 10/1/1998 Mississippi Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1250 9/30/1998 Alabama Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1249 9/28/1998 Florida Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 3133 9/28/1998 Alabama Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 3132 9/28/1998 Mississippi Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 3131 9/25/1998 Florida Hurricane Georges Emergency Declaration 2248 9/25/1998 Washington Columbia County Fire Management Assistance Declaration 1247 9/24/1998 Puerto Rico Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1248 9/24/1998 Virgin Islands Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration 1245 9/23/1998 Texas Tropical Storm Frances Major Disaster Declaration Tropical Storm Frances and 1246 9/23/1998 Louisiana Hurricane Georges Major Disaster Declaration Hurricane Georges (Direct 3129 9/21/1998 Virgin Islands Federal -

May 2014 San Diego County Wildfires After Action Report

- May 2014 San Diego County Wildfires After Action Report County of San Diego May 2014 San Diego County Wildfires Helen N. Robbins-Meyer Chief Administrative Officer Ron Lane Deputy Chief Administrative Officer, Public Safety Group Holly Crawford Director, Office of Emergency Services Board of Supervisors: First District Greg Cox Second District Dianne Jacob Third District Dave Roberts Fourth District Ron Roberts Fifth District Bill Horn June 2014 Acknowledgements The following San Diego County agencies contributed to this report: San Diego County Sheriff San Diego County District Attorney American Red Cross of San Diego/Imperial Counties 2-1-1 CAL FIRE Joint Arson Task Force Information Exchange Caltrans City of Carlsbad City of Escondido City of San Diego City of San Marcos California State University San Marcos US Department of Homeland Security Federal Protective Service This report includes commentary on components of the regional response but is not intended as a comprehensive analysis for all responding agencies. The report focuses on the response of County of San Diego (County) departments with recognition that cities and responding agencies will conduct their own after action planning process. Photos of the Cocos fire courtesy CAL FIRE and ©Kevin Pack/K.E. Pack Photography Contents Executive Summary ______________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Scope of the Report _______________________________________________________________________________________ 8 Disaster Overview ________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Firebuster—A Web Application for High-Resolution Fire Weather

United States Department of Agriculture FireBuster—A Web Application for High-Resolution Fire Weather Modeling Shyh-Chin Chen, John Benoit, Jack Ritchie, Yunfei Zhang, Hann-Ming Henry Juang, Ying-Ju Chen, and Tom Rolinski Forest Pacific Southwest General Technical Report July D E E P R Service Research Station PSW-GTR-264 2019 A U R T LT MENT OF AGRICU In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Managing Wildfire Risk and Litigation Mark Bluestein

7/30/2014 BREAKOUT SESSION Managing Wildfire Risk and Litigation AEGIS 2014 POLICYHOLDERS’ CONFERENCE MANAGING WILDFIRE RISK AND LITIGATION Mark Bluestein Vice President/Counsel AEGIS Claims AEGIS 2014 POLICYHOLDERS’ CONFERENCE 1 7/30/2014 CREATING WILDFIRE RESILIENCE THROUGH PREPAREDNESS Joe Vaccaro Electric Transmission & Distribution Project Management, Operations Manager San Diego Gas & Electric AEGIS 2014 POLICYHOLDERS’ CONFERENCE © 2012 San Diego Gas & Electric Company. All copyright and trademark rights reserved. Overview of SDG&E’s Service Territory • SDG&E supplies power to 1.4 million business/residential accounts in a 4,100 square-mile service area • SDG&E overhead facilities ~ 1,800 miles of electric transmission lines and 7,000 miles of electric distribution lines. • SDG&E has developed a Community Fire Safety Program that improves power line safety, increases reliability and helps our region’s overall emergency preparedness AEGIS 2014 POLICYHOLDERS’ CONFERENCE 2 7/30/2014 Overview of SDG&E’s Service Territory • SDG&E’s significant enhancements since 2007 Early and predictive weather information System design for both transmission and distribution systems Operational changes Supplemental inspection and maintenance practices Robust vegetation management program Support and reactive measures to aggressively pursue active fires • These changes have been made to improve safety and to reduce the potential for electric facilities to be an ignition source, and ongoing efforts will further reduce fire risk AEGIS 2014 POLICYHOLDERS’ -

2. Special Presentations A

RANCHO SANTA FE FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING AGENDA Rancho Santa Fe FPD November 9, 2016 Board Room – 18027 Calle Ambiente 1:00 pm PT Rancho Santa Fe, California 92067 Regular Meeting RULES FOR ADDRESSING BOARD OF DIRECTORS Members of the audience who wish to address the Board of Directors are requested to complete a form near the entrance of the meeting room and submit it to the Board Clerk. Any person may address the Board on any item of Board business or Board concern. The Board cannot take action on any matter presented during Public Comment, but can refer it to the Administrative Officer for review and possible discussion at a future meeting. As permitted by State Law, the Board may take action on matters of an urgent nature or which require immediate attention. The maximum time allotted for each presentation is FIVE (5) MINUTES. Pledge of Allegiance 1. Roll Call 2. Special Presentations a. Administrative Personnel Recognition will be given to District staff for exceptional efforts and service 3. Motion waiving reading in full of all Resolutions/Ordinances 4. Public Comment All items listed on the Consent Calendar are considered routine and will be enacted by one motion without discussion unless Board Members, Staff or the public requests removal of an item for separate discussion and action. The Board of Directors has the option of considering items removed from the Consent Calendar immediately or under Unfinished Business. 5. Consent Calendar a. Board of Directors Minutes • Board of Directors minutes of October 12, 2016 ACTION REQUESTED: Approve b. -

March 25, 2020 12730 High Bluff Drive, Suite 260 San

March 25, 2020 Subject: Project Name - Trails at Carmel Mountain Ranch/652519, Community - Carmel Mountain Ranch Council District – 5, Environmental Impact Report, Attn: E. Shearer-Nguyen To Whom It May Concern: I am president and founder of CMR United, a nonprofit formed in conjunction with the concerned citizens of Carmel Mountain Ranch. CMR United has over 500 volunteers who support the Carmel Mountain Ranch Community plan. We do not support the proposed changes to the General Plan Amendment. We have many concerns in all the areas that your department will be reviewing. This correspondence will outline the most significant impacts, Transportation/Circulation, Fire Safety, Public Services and Facilities, Visual Effect, and Neighborhood Character. The creation of 1,200 new multi-family units will create severe negative impacts on the community. The transportation impact analysis indicated the project would increase daily trips by approximately 8,000 car trips per day. If approved, the population of the community would increase by 25%. The proposed plan does not add any additional capacity to residential streets. The planned increase of 1,200 units in Carmel Mountain is joined by another 1,500 units directly across the highway on Carmel Mountain Road. All the new residents would be utilizing retail shopping areas in Carmel Mountain Ranch. Parking in these shopping areas is already at capacity. It is difficult for current residents to find a parking place at such retailers as: Costco, Ralphs, Trader Joes, and Home Depot. Further, Carmel Mountain Ranch has significant parking issues on the surface streets. The parking problems exist near the multi-family units in the community. -

Bernardo Fire May 2014

Bernardo Fire May 2014 After Action Report City of San Diego Response AFTER ACTION REPORT MAY 2014 BERNARDO FIRE CITY OF SAN DIEGO RESPONSE TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ......................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 2 INCIDENT OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................... 3 Fire and Law Enforcement Agencies Supporting the Bernardo Fire .......................................... 4 Significant Events ....................................................................................................................... 5 KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................ 6 FIRE APPARATUS/EQUIPMENT INVENTORY AND LOGISTICS ...................................................... 13 Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Change ............................................................... 14 MASS NOTIFICATION SYSTEM & EVACUATIONS ........................................................................ 17 Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Change ............................................................... 17 AIR OPERATIONS ......................................................................................................................... -

UNM 2015 Hazard Mitigation Plan

HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN NOVEMBER 2015 November 2015 Table of Contents Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Adoption by the University of New Mexico .................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Vision and Purpose.................................................................................................................................. 1 University of New Mexico Planning Area: History, Demographics, Economy, and Geography ........ 1 University of New Mexico ................................................................................................................... 1 Main and Branch Campus Demographics ........................................................................................ 13 Academic and Research Programs ................................................................................................... 14 Athletics ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Campus Economy .............................................................................................................................. 16 UNM Utilities and Infrastructure .................................................................................................... -

Incident Scenarios Collection for Public Safety Communications Research Framing the Context of Use

NISTIR 8181 Incident Scenarios Collection for Public Safety Communications Research Framing the Context of Use Yee-Yin Choong Shaneé Dawkins Kristen Greene Mary Theofanos This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8181 NISTIR 8181 Incident Scenarios Collection for Public Safety Communications Research Framing the Context of Use Yee-Yin Choong Shaneé Dawkins Kristen Greene Information Access Division Information Technology Laboratory Mary Theofanos Office of Data and Informatics Material Measurement Laboratory This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8181 June 2017 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Kent Rochford, Acting NIST Director and Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technolog This publication is available freeof charge from: Incident Scenarios ( Collection for Public Safety Communications Research ( Framing the Context of Use https://doi.org VERSION: 1.0 JUNE 2017 /10.6028/NIST.IR. 8181 Contacts: This document was developed by the Public Safety Communications Research (PSCR) Usability Team at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). National Institute of Standards and Technology Communications Technology Laboratory Gaithersburg, MD 20899 This publication is available freeof charge from: Yee-Yin Choong Industrial Psychologist 301.975.3248 [email protected] Shaneé Dawkins Computer Scientist 301.975.4464 [email protected] Kristen Greene Cognitive Scientist 301.975.8119 [email protected] https://doi.org Mary Theofanos Computer Scientist 301.975.5889 /10.6028/NIST.IR. [email protected] 8181 ii Table of Contents Contacts: ................................................................................................................................. ii Revision Record ......................................................................................................................