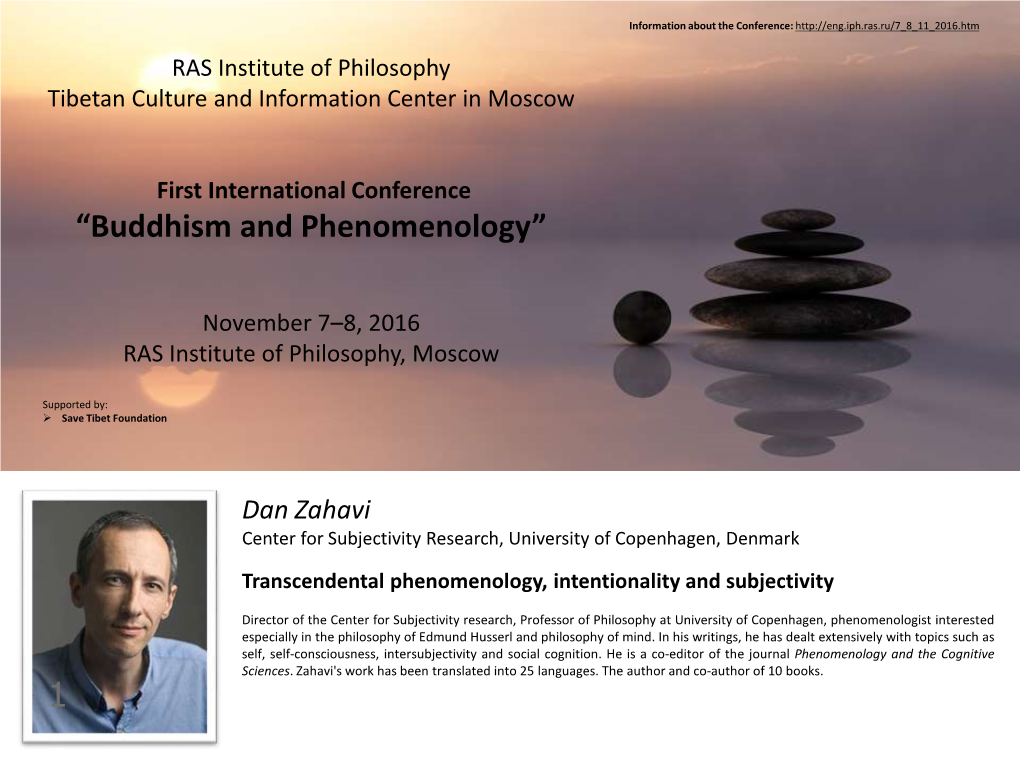

Buddhism and Phenomenology”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007

Danish National Research Foundation: Center for Subjectivity Research University of Copenhagen Njalsgade 140-142 DK-2300 Copenhagen S Denmark Phone: (+45) 3532 86 80 Fax: (+45) 3532 8681 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cfs.ku.dk Annual report: January 1 - December 31, 2007 Content 1. Introduction 2. Staff 3. External funding for 2007 4. Research 5. Foreign visitors 6. Activities organized by the Center 7. Teaching, supervision, evaluation 8. Various academic and administrative tasks 9. Editorial tasks 10. Collaboration (national and international) 11. Talks and lectures 12. Publications 13. Submitted/accepted manuscripts 1. Introduction The Center is an interdisciplinary "Center of Excellence" funded by the Danish National Research Foundation, with supplementary funding from the University of Copenhagen (Faculty of Humanities, Faculty of Theology and Faculty of Health Sciences). The current research program of the center, which runs from March 1, 2007 – February 28, 2012, is entitled "The Self: An Integrative Approach". The Center’s research is divided into six sections: • Self and consciousness • Core self and extended self: A viable distinction? • Infantile self-experience: A developmental perspective • Self, emotions and understanding • Disorders of self • Self and normativity Although the Center’s research is mainly focused on conceptual and theoretical issues, it is not a narrowly conceived philosophical investigation, but one that is enriched and informed by empirical research, and which involves active collaboration with psychologists, psychiatrists and neuroscientists. 1 During 2007 the Center organized, co-organized, and/or co-sponsored 7 conferences and workshops (with more than 140 speakers) as well as 10 individual guest lectures by invited speakers, and it had more than 45 foreign visitors. -

Being Someone

PSYCHE: http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/ Being Someone Dan Zahavi Danish National Research Foundation: Center for Subjectivity Research University of Copenhagen Denmark © Dan Zahavi [email protected] PSYCHE 11 (5), June 2005 KEYWORDS: Self, Phenomenology, Self-experience, Metzinger COMMENTARY ON: Metzinger, T. (2003) Being No One. The Self-Model Theory of Subjectivity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press xii + 699pp. ISBN: 0-262-13417-9. ABSTRACT: My discussion will focus on what is arguable the main claim of Being No One: That no such things as selves exist in the world and that nobody ever was or had a self. In discussing to what extent Metzinger can be said to argue convincingly for this claim, I will also comment on his methodological use of pathology and briefly make some remarks vis-à-vis his understanding and criticism of phenomenology. D. Zahavi: Being Someone 1 PSYCHE: http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/ Being No One is a book that engages with some truly interesting questions. It is also a very long book, and it will be impossible to deal with all its suggestions and to discuss all the problems it raises in a short commentary. What I intend to do in the following is to focus on three areas. My emphasis will be on Metzinger’s main claim: no such things as selves exist in the world and nobody ever was or had a self. In discussing to what extent Metzinger can be said to argue convincingly for this claim in Being No One, I will also comment on his methodological use of pathology and briefly make some remarks vis-à- vis his understanding and criticism of phenomenology. -

Protosociology Volume 36/2019: Senses of Self … 4 Contents

ProtoSociology — www.protosociology.de — An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research ProtoSociology is an interdisciplinary journal which crosses the borders of philosophy, social sciences, and their corresponding disciplines for more than two decades. Each issue concentrates on a specific topic taken from the current discussion to which scientists from different fields contri- bute the results of their research. ProtoSociology is further a project that examines the nature of mind, Senses of Self language and social systems. In this context theoretical work has been | Approaches to Pre-Reflective done by investigating such theoretical concepts like interpretation and Self-Awareness (social) action, globalization, the global world-system, social evolution, and the sociology of membership. Our purpose is to initiate and enforce Edited by Marc Borner, Manfred Frank, and Kenneth Williford basic research on relevant topics from different perspectives and tradi- tions. Editor: Gerhard Preyer Senses of Self Vol. 36: Vol. ProtoSociology } Vol. 35: Joint Commitments Vol. 34: Meaning and Publicity Vol. 33: The Borders of Global Theory – Reflections from Within and Without Vol. 32: Making and Unmaking Modern Japan Volume 36, 2019 © 2019 Gerhard Preyer Frankfurt am Main http://www.protosociology.de [email protected] Erste Auflage / first published 2019 ISSN 1611–1281 Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Natio nal bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Je de Ver wertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zu stimmung der Zeitschirft und seines Herausgebers unzulässig und strafbar. -

Empathy≠Sharing: Perspectives From

Consciousness and Cognition 36 (2015) 543–553 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Consciousness and Cognition journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/concog Empathy – sharing: Perspectives from phenomenology and developmental psychology ⇑ Dan Zahavi a, , Philippe Rochat b a Center for Subjectivity Research, Department of Media, Cognition and Communication, University of Copenhagen, Njalsgade 140-142, Copenhagen S, Denmark b Department of Psychology, Emory University, 463 Psychology Building, 36 Eagle Row, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA article info abstract Article history: We argue that important insights regarding the topic of sharing can be gathered from Received 30 December 2014 phenomenology and developmental psychology; insights that in part challenge wide- Revised 12 May 2015 spread ideas about what sharing is and where it can be found. To be more specific, we first Accepted 13 May 2015 exemplify how the notion of sharing is being employed in recent discussions of empathy, Available online 10 June 2015 and then argue that this use of the notion tends to be seriously confused. It typically con- flates similarity and sharing and, more generally speaking, fails to recognize that sharing Keywords:: proper involves reciprocity. As part of this critical analysis, we draw on sophisticated anal- Empathy yses of the distinction between empathy and emotional sharing that can be found in early Affective sharing Phenomenology phenomenology. Next, we turn to developmental psychology. Sharing is not simply one Developmental psychology thing, but a complex and many-layered phenomenon. By tracing its early developmental trajectory from infancy and beyond, we show how careful psychological observations can help us develop a more sophisticated understanding of sharing than the one currently employed in many discussions in the realm of neuroscience. -

An Interview with Dan Zahavi 47

108 Philosophical Interviews 114 Philosophical Interviews Husserl, self and others: an interview with Dan Zahavi 47 Picture source: Dan Zahavi's archives. How did you originally get interested in philosophy? I met philosophy early. I read much as a child, and occasionally came across refer- ences to philosophy. I didn’t understand what it meant, but I was curious, and when I was 12 years old, I asked my mother to buy me a copy of Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy: the Lives and Opinions of the Greater Philosophers. I can’t claim to have understood much at that age, but Durant’s account of Plato was still so in- spiring that I there and then decided that I wanted to study philosophy. And that was basically a decision I stuck to, and which I have never regretted. It made me opt for modern languages in the gymnasium, since I wanted to learn German so that I could read Kant and study in Germany. Right after the gymnasium, I enrolled as a philosophy student at the University of Copenhagen. Initially I was mostly in- terested in the history of philosophy (Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas and Kant), but 47 An earlier version of the present interview appeared in Danish in F.K. Thomsen & J.v.H. Holtermann, eds. 2010. Filosofi: 5 spørgsmål . Automatic Press. AVANT Volume III, Number 1/2012 www.avant.edu.pl/en 115 eventually I got interested in Husserl, which I back then took to be an interesting synthesis of Aristotle and Kant. So I decided to write my MA thesis on him, and it was on this occasion that I finally realized my plans about studying abroad. -

Penultimate Draft. Final Version Published in T. Toadvine & L. Embree (Eds.): Merleau-Ponty's Reading of Husserl. Kluwer

Penultimate draft. Final version published in T. Toadvine & L. Embree (eds.): Merleau-Ponty's Reading of Husserl. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 2002, 3-29. Please quote only from published version. Dan Zahavi University of Copenhagen MERLEAU-PONTY ON HUSSERL. A REAPPRAISAL If one comes to Phénoménologie de la perception after having read Sein und Zeit (or Prolegomena zur Geschichte des Zeitbegriffs) one will be in for a surprise. Both works contain a number of both implicit and explicit references to Husserl, but the presentation they give is so utterly different, that one might occasionally wonder whether they are referring to the same author. Thus nobody can overlook that Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of Husserl differs significantly from Heidegger’s. It is far more charitable. In fact, when evaluating the merits of respectively Husserl and Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty often goes very much against the standard view. This is not only the case in his notorious remark on the very first page of Phénoménologie de la Perception where he declares that the whole of Sein und Zeit is nothing but an explication of Husserl’s notion of Lifeworld, but also - to give just one further example - in one of his Sorbonne-lectures, where Merleau-Ponty writes that Husserl took the issue of historicity far more seriously than Heidegger.1 1. Husserl and the Merleau-Pontyeans My point of departure will be the slightly surprising fact that a large number of Merleau-Ponty scholars have questioned the validity of Merleau-Ponty’s reading of Husserl. Let me illustrate this with a few references. -

The Concept of Personhood in the Phenomenology of Edmund Husserl

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The onceptC of Personhood in the Phenomenology of Edmund Husserl Colin J. Hahn Marquette University Recommended Citation Hahn, Colin J., "The oncC ept of Personhood in the Phenomenology of Edmund Husserl" (2012). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 193. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/193 THE CONCEPT OF PERSONHOOD IN THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF EDMUND HUSSERL by Colin J. Hahn, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2012 ABSTRACT THE CONCEPT OF PERSONHOOD IN THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF EDMUND HUSSERL Colin J. Hahn, B.A., M.A. Marquette University, 2012 This dissertation attempts to articulate the concept of personhood in Husserl. In his research manuscripts, Husserl recognized the need for a concrete description of subjectivity that still remained within the transcendental register. The concept of personhood, although never fully worked out, is intended to provide this description by demonstrating how the embodied, enworlded, intersubjective, and axiological dimensions of experience are integrated. After briefly outlining the characteristics of a transcendental phenomenological account of personhood, this dissertation outlines the essential structures of personhood. The person, for Husserl, includes the passive dimension with the instinctive and affective dimensions -

Broaching the Difference Between Intersubjectivity and Intersubjection Inspired by the Feminist Critique1

Broaching the Difference Between Intersubjectivity and Intersubjection Inspired 1 by the Feminist Critique Iraklis Ioannidis (University of Glasgow) Abstract In Critical Philosophy and, particularly, phenomenology ‘inter- subjectivity’ is a core theme of analysis. As Zahavi put it, intersub- jectivity, “be it in the form of a concrete self—other relation, a so- cially structured life-world, or a transcendental principle of justifica- tion, is ascribed an absolutely central role by phenomenologists.” Yet, when dealt with in this way, ‘intersubjectivity,’ as a conceptual attempt to refer to our ontology, to who we are, conceals other phe- nomena. In this paper an attempt is being made to articulate the phe- nomenon of authentic intersubjectivity by contrasting it with what we refer to as intersubjection, when only one subjectivity is express- ing the Other by expressing the Other through the same, as in the case of empathy. Following the feminist critique we identify inter- subjection as the tendency to reduce the Other to one’s own catego- ries hence muting them or, at best, imposing on them a category which is intended from one subject only. Following Sartre, we articu- late intersubjectivity as a reciprocal, bilateral relation where subjec- 1 This paper has been presented at SEP-FEP 2016, in Lectures with Dan Zahavi on Self and Other 2016 at the University of Ruhr (Ruhr- Universität Bochum), and in the Annual Meeting of the Existential Philosophy and Literature Network Conference 2017 at the University of Glasgow. I would like to thank Susan Stuart and Olivier Salazar-Ferrer for their comments on the first draft of this paper, Dan Zahavi and the attendees of SEP-FEP for their valuable comments and contributions on the previously revised version of this paper. -

Dan Zahavi, Self and Other: Exploring Subjectivity, Empathy, and Shame Oxford: Oxford University Press, Óþõ¦ ISBN: Éß-Þ-ÕÉ-É¢Éþä-Õ

Dan Zahavi, Self and Other: Exploring Subjectivity, Empathy, and Shame Oxford: Oxford University Press, óþÕ¦ ISBN: Éß-þ-ÕÉ-É¢Éþä-Õ Merike Reiljan Department of Philosophy, University of Tartu Keywords: minimal self, social cognition, empathy, phenomenology Õ. Introduction Dan Zahavi’s Self and Other: Exploring Subjectivity, Empathy, and Shame is an elaboration of the author’s phenomenological account of selfhood, the latest longer work in a series of publications on the topic. e focus of this monograph is on the relation between the self and the other. Zahavi defends the multidimensional model of the self and argues that the minimal self, the most basic form of self that all subjective creatures share, is presocial. How- ever, there are also other dimensions of the self that are formed through so- cial means. Self and Other is an exploration of the interconnection between the social and the presocial aspects of selfhood via an extended investigation of the phenomenon of empathy. It addresses the question whether under- standing the self to be a presocial and rst-personal phenomenon at the most basic level allows for a proper account of both intersubjectivity and the social nature of humans. Drawing upon insights provided by the phenomenologi- cal accounts of Edmund Husserl, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Max Scheler, and Alfred Schutz, Zahavi defends the notion of a minimal self from the critique that it is overly Cartesian. He argues that since the basic form of empathy, which is necessary for developing any social dimen- sion of selfhood, entails the preservation of self-other dierentiation, the rst-personal experiential self must rather be regarded as a prerequisite for a satisfactory account of intersubjectivity and sociability. -

Philosophical Issues: Phenomenology Evan Thompson and Dan Zahavi

Philosophical Issues: Phenomenology Evan Thompson and Dan Zahavi ∗ Abstract Current scientific research on consciousness aims to understand how consciousness arises from the workings of the brain and body, as well as the relations between conscious experience and cognitive processing. Clearly, to make progress in these areas, researchers cannot avoid a range of conceptual issues about the nature and structure of consciousness, such as the following: What is the relation between intentionality and consciousness? What is the relation between self-awareness and consciousness? What is the temporal structure of conscious experience? What is it like to imagine or visualize something, and how is this type of experience different from perception? How is bodily experience related to self-consciousness? Such issues have been addressed in detail in the philosophical tradition of phenomenology, inaugurated by Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) and developed by numerous other philosophers throughout the 20th century. This chapter provides an introduction to this tradition and its way of approaching issues about consciousness. We first discuss some features of phenomenological methodology and then present some of the most important, influential, and enduring phenomenological proposals about various aspects of consciousness. These aspects include intentionality, self-awareness and the first-person perspective, time-consciousness, embodiment, and intersubjectivity. We also highlight a few ways of linking phenomenology and cognitive ∗ Order of authors was set alphabetically, and each author did equal work. 2 science in order to suggest some directions consciousness research could take in the years ahead. Keywords Phenomenology, intentionality, embodiment, time-consciousness, temporality, self- awareness, intersubjectivity, neurophenomenology 1. Introduction Contemporary Continental perspectives on consciousness derive either whole or in part from Phenomenology, the philosophical tradition inaugurated by Edmund Husserl (1859- 1938). -

Zahavi, Clarity, Zahavi Brings Back the Central Importance of the First-Person Perspective.” Phenomenology Can Demonstrate Its Vitality and Contemporary Relevance

4745zahavi 12/29/05 9:13 AM Page 1 Ph 0-262-24050-5 oto Subj b y Scanpix/ ,!7IA2G2-ceafaf!:t;K;k;K;k ectivi Mo r ten philosophy of mind J uhl O Subjectiviy and Selhood y Subjectiviy and Selhood “Zahavi delivers a critical phenomenological account of the subjectivity of experience that shows how Investigating the First-Person Perspective phenomenology is not just a description but an analysis that can contribute to explanations of and consciousness, self, and intersubjectivity. Staying deftly on target, Zahavi challenges higher-order representational theory and standard theory-of-mind approaches to social cognition. He pushes the Investigating the First-Person Perspective phenomenological envelope and engages in an original way with traditional analytic philosophy of mind Sel and more recent lines of thought that are drawn from the cognitive sciences. To the list of classic phe- Dan Zahavi nomenologists from whom Zahavi draws we need to add one more: Zahavi himself.” h Dan Zahavi is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Shaun Gallagher, Professor and Chair, Department of Philosophy, University of Central Florida What is a self? Does it exist in reality or is it a mere social Center for Subjectivity Research at the University of Copen- ood construct—or is it perhaps a neurologically induced illusion? hagen and the author of Self-Awareness and Alterity in Husserl’s “Zahavi’s book is a valuable contribution to the current interdisciplinary discussion of consciousness. The legitimacy of the concept of the self has been questioned Phenomenology. In simple and direct language, he gives us a full phenomenological investigation of subjectivity and by both neuroscientists and philosophers in recent years. -

Dan Zahavi University of Copenhagen HUSSERL's INTERSUBJECTIVE TRANSFORMATION of TRANSCENDENTAL PHILOSOPHY If One Interprets

Dan Zahavi University of Copenhagen HUSSERL'S INTERSUBJECTIVE TRANSFORMATION OF TRANSCENDENTAL PHILOSOPHY If one interprets transcendental subjectivity as an isolated ego and in the spirit of the Kantian tradition ignores the whole task of establishing a transcendental community of subjects, then every chance of reaching a transcendental self- and world-knowledge is lost. Krisis (Ergänzung), 120. A dominant trait in the philosophy of our century has been the critique of the philosophy of subjectivity. Among transcendental philosophers this critique has been taken into consideration most conspicuously by K.-O. Apel, who explicitly calls for an intersubjective transformation of transcendental philosophy. Not the single, isolated, self-aware ego, but language community, that is intersubjectivity, has to be regarded as the reality-constituting principle. It is possible to find a similar interest in and treatment of intersubjectivity in Husserl. From the winter 1910/11 and until his death, he worked thoroughly with different aspects of the problem of intersubjectivity, and left behind an almost inestimable amount of analyses, that from a purely quantitative point of view by far exceeds the treatment given this topic by any of the later phenomenologists.1 In the following, I will try to provide a systematic outline of Husserl’s investigations, and at the same time argue that Husserl, whose position has often been regarded as solipsistic, was actually occupied with the elaboration of a transcendental theory of intersubjectivity.2 I. The easiest way to introduce Husserl’s analysis of intersubjectivity is through his concept of the lifeworld, since Husserl claims that it is intersubjective through and through.