Technology of Breadmaking VISIT OOR FCOD OCIEI:\(E SI'ie En" 'IHE 1A1EB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Lehigh County

\B7 L5H3 Class _^^ ^ 7 2- CoKiightN". ^A^ COFmiGHT DEPOSIT 1/ I \ HISTORY OF < Lehigh . County . Pennsylvania From The Earliest Settlements to The Present Time including much valuable information FOR THE USE OF THE ScDoolSt Families ana Cibrarics, BY James J. Hauser. "A! Emaus, Pknna., TIMES PURIJSHING CO. 1 901, b^V THF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, Two Copies Recfived AUG. 31 1901 COPYBIOHT ENTRV ^LASS<^M<Xa No. COPY A/ Entered according to Die Act of Congress, in the year 1901, By JAMES J. HAUSER, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. All rights reserved. OMISSIONS AND ERRORS. /)n page 20, the Lehigh Valley R. R. omitted. rag6[29, Swamp not Swoiup. Page 28, Milford not Milfod. Page ol, Popnlatioii not Populatirn. Page 39, the Daily Leader of Ailentown, omitted. Page 88, Rev. .Solomon Neitz's E. name omitted. Page i)2,The second column of area of square miles should begin with Hanover township and not with Heidelberg. ^ INTRODUCTION i It is both interesting and instructive to study the history of our fathers, to ^ fully understand through what difficulties, obstacles, toils and trials they went to plant settlements wliich struggled up to a position of wealth and prosperity. y These accounts of our county have been written so as to bring before every youth and citizen of our county, on account of the growth of the population, its resources, the up building of the institution that give character and stability to the county. It has been made as concise as possible and everything which was thought to be of any value to the youth and citizen, has been presented as best as it could be under the circumstances and hope that by perusing its pages, many facts of interest can be gathered that will be of use in future years. -

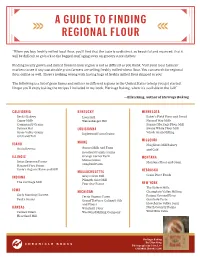

A Guide to Finding Regional Flour

A GUIDE TO FINDING REGIONAL FLOUR “When you buy freshly milled local flour, you’ll find that the taste is so distinct, so beautiful and nuanced, that it will be difficult to go back to the bagged stuff aging away on grocery store shelves. Finding locally grown and milled flours in your region is not as difficult as you think. Visit your local farmers’ markets to see if any sustainable grain farmers are selling freshly milled wheat flour. You can search for regional flour online as well. There’s nothing wrong with having bags of freshly milled flour shipped to you! The following is a list of grain farms and millers in different regions in the United States to help you get started. I hope you’ll enjoy baking the recipes I included in my book, Heritage Baking, when it’s available in the fall!” —Ellen King, author of Heritage Baking CALIFORNIA KENTUCKY MINNESOTA Beck’s Bakery Louismill Baker’s Field Flour and Bread Capay Mills Weisenberger Mill Natural Way Mills Community Grains Sunrise Heritage Flour Mill Farmer Mai LOUISIANNA Swany White Flour Mill Grass Valley Grains Whole Grain Milling Inglewood Farm Grains Grist and Toll MISSOURI MAINE IDAHO Neighbors Mill Bakery Aurora Mills and Farm Grain Revival and Café Bouchard Family Farms ILLINOIS Grange Corner Farm MONTANA Maine Grains Brian Severson Farms Montana Flour and Grain Songbird Farm Hazzard Free Farms Janie’s Organic Farm and Mill MASSACHUSETTS NEBRASKA Grain Place Foods INDIANA Gray’s Grist Mill Plimoth Grist Mill The Carthage Mill Four Star Farms NEW YORK The Birkett Mills IOWA MICHIGAN -

Grist Milling in Eighteenth-Century Virginia Society: Legal, Social, and Economic Aspects

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1969 Grist Milling in Eighteenth-Century Virginia Society: Legal, Social, and Economic Aspects Paul Brent Hensley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons, Economic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hensley, Paul Brent, "Grist Milling in Eighteenth-Century Virginia Society: Legal, Social, and Economic Aspects" (1969). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624679. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-n6hz-0862 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. aim nzuuuiein xssit zimi cammr vxmvnk society* tMGAL SOCIAL AMD ECOHOMC ASPECTS a rtiaolo Tmeslti to tl« faeu: y of tbs Deport— it of History fho Colleg of Kllll— sad Hf :y in Vlvgisis la fs tux FSlfll nt Stf Che ftafi&r— o for the Oegr— of V aitff of Arts 1* foi l arose Ho—ley 1960 ProQuest Number: 10625099 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Spicy Cheese Bread - Brown Eyed Baker Spicy Cheese Bread

8/31/2020 Spicy Cheese Bread - Brown Eyed Baker Spicy Cheese Bread This recipe makes a huge loaf of a rich brioche-like bread loaded with provolone and Monterey Jack cheeses, and speckled with crushed red pepper flakes. Course Bread Cuisine American Prep 40 minutes Cook 50 minutes Resting time 4 hours Total 5 hours 30 minutes Servings 12 servings (1 loaf) Calories 306 kcal Author Michelle Ingredients For the Bread: 3¼ cups all-purpose flour ¼ cup granulated sugar 1 tablespoon instant rapid-rise yeast 1½ teaspoons red pepper flakes 1¼ teaspoons salt ½ cup warm water (110 degrees) 2 eggs 1 egg yolk 4 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted 6 ounces Monterey Jack cheese cut into ½-inch cubes (about 1½ cups), at room temperature 6 ounces provolone cheese cut into ½-inch cubes (about 1½ cups), at room temperature For the Topping: 1 egg lightly beaten 1 teaspoon red pepper flakes 1 tablespoon unsalted butter at room temperature Directions 1. Make the Bread: In the bowl of a stand mixer, whisk together the flour, sugar, yeast, red pepper flakes and salt. In a liquid measuring cup, whisk together the warm water, eggs, egg yolk, and melted butter. Add the egg mixture to the flour mixture in the mixing bowl. Using a dough hook, knead on medium speed until the dough clears the bottom and sides of the bowl, 4 to 8 minutes. 2. Shape the dough into a ball and transfer to a greased bowl, turning to coat the dough. Cover with plastic wrap and let rise in a warm place until doubled in size, 1½ to 2 hours. -

The Science of Mashing by Jamie Ramshaw

The Science of Mashing Jamie Ramshaw M Brew IBD 25/10/17 Purpose Purpose • Extract the starch from a source • Convert the starch into a sugar that can be utilised by Yeast • Control the extent of conversion • Extract what is wanted and leave behind what is not • Starch source • Water • Process A Source of Starch - Barley Barley Barley • Contains: – Starch – Protein – Beta Glucans and Gums – Polyphenol in husk – Need to prepare the barley for quick extraction and degradation at the brewery – Malting Germination Harvest • Grown on light soil • Winter and spring varieties • Harvest Winters then Wheat then Springs Storage • Condition kept to prevent microbial and insect infestation • Moisture content max • Temperature max • Monitored regularly • Held here until dormancy breaks • Can force dormancy to break • Micro malting used to assess the barley and configure the barley’s best process Steep • Soaking and air rests • Mimics rainfall • Triggers germination in non dormant grain Gemination Kiln • Stops Germination • Drive off water by free and forced drying • Creation of colour and flavour can occur here • Malt • A stable parcel of easy to access starch Germination and Kilning Approved UK Barley • There are approved varieties of barley • Must pass through a number of standards in order to be approved • Seed • Agronomic • Malting • Brewing Malt Specification Germination Mashing Chemistry Mashing Chemistry Mashing Chemistry Mashing Chemistry Mashing Chemistry Mashing Chemistry Optimal Conditions Water Water • pH is the logarithm of the reciprocal -

PRUDENT FOOD STORAGE: Questions & Answers

Version 4.0 Updated December 2003 Supersedes Version 3.50 PRUDENT FOOD STORAGE: Questions & Answers Alan T. Hagan Author of The Prudent Pantry: Your Guide to Building a Food Insurance Program "In this work, when it shall be found that much is omitted, let it not be forgotten that much likewise is performed." Samuel Johnson, 1775, upon completion of his dictionary. Courtesy of James T. Stevens ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Diana Hagan, my wife, for endless patience in the years since I created this FAQ; Susan Collingwood for sage advice; Lee Knoper; BarbaraKE; Gary Chandler; Skipper Clark, author of Creating the Complete Food Storage Program; Denis DeFigueiredo; Al Durtschi for resources and encouragement; Craig Ellis; Pyotr Filipivich; Sandon A. Flowers; Amy Gale, editor of the rec.food.cooking FAQ; Geri Guidetti, of the Ark Institute; Woody Harper; Higgins10; Robert Hollingsworth; Jenny S. Johanssen; Kahless; James T. Stevens, author of Making The Best of Basics; Amy Thompson (Saco Foods); Patton Turner; Logan VanLeigh; Mark Westphal; Rick Bowen; On-Liner and The Rifleman in the UK; Myal in Australia; Rosemarie Ventura; Rex Tincher; Halcitron; Noah Simoneaux; a number of folks who for reasons sufficient unto themselves wish to remain anonymous; and last, but certainly not least, Leslie Basel, founding editor of the rec.food.preserving FAQ, without whom I'd never have attempted this in the first place. The home of the Prudent Food Storage FAQ can be found at: http://athagan.members.atlantic.net/Index.html Check there to be sure of the most current FAQ version. Updated: 9/18/96; 4/16/97; 7/21/97; 10/20/97; 9/15/98; 11/02/99; 12/01/03 Copyright ã 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2003. -

A Multi-Parameter, Predictive Model of Starch Hydrolysis in Barley Beer Mashes

beverages Article A Multi-Parameter, Predictive Model of Starch Hydrolysis in Barley Beer Mashes Andrew Saarni 1, Konrad V. Miller 1,2 and David E. Block 1,2,* 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (K.V.M.) 2 Department of Viticulture and Enology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-530-752-0381 Received: 22 May 2020; Accepted: 1 October 2020; Published: 13 October 2020 Abstract: A key first step in the production of beer is the mashing process, which enables the solubilization and subsequent enzymatic conversion of starch to fermentable sugars. Mashing performance depends primarily on temperature, but also on a variety of other process parameters, including pH and mash thickness (known as the “liquor-to-grist” ratio). This process has been studied for well over 100 years, and yet essentially all predictive modeling efforts are alike in that only the impact of temperature is considered, while the impacts of all other process parameters are largely ignored. A set of statistical and mathematical methods collectively known as Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is commonly applied to develop predictive models of complex processes such as mashing, where performance depends on multiple parameters. For this study,RSM was used to design and test a set of experimental mash conditions to quantify the impact of four process parameters—temperature (isothermal), pH, aeration, and the liquor-to-grist ratio—on extract yield (total and fermentable) and extract composition in order to create a robust, yet simple, predictive model. -

The Rise and Fall of Bread in America Amanda Benson Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected]

Johnson & Wales University ScholarsArchive@JWU Academic Symposium of Undergraduate College of Arts & Sciences Scholarship Spring 2013 The Rise and Fall of Bread in America Amanda Benson Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/ac_symposium Part of the Cultural History Commons, Marketing Commons, and the Other Business Commons Repository Citation Benson, Amanda, "The Rise and Fall of Bread in America" (2013). Academic Symposium of Undergraduate Scholarship. 21. https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/ac_symposium/21 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ScholarsArchive@JWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Symposium of Undergraduate Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarsArchive@JWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Honors Thesis The Rise and Fall of Bread in America Amanda Benson February 20, 2013 Winter 2013 Chef Mitch Stamm Benson 2 Abstract: Over the last century bread has gone through cycles of acceptance and popularity in the United States. The pressure exerted on the American bread market by manufacturers’ advertising campaigns and various dietary trends has caused it to go through periods of acceptance and rejection. Before the industrialization of bread making, consumers held few negative views on bread and perceived it primarily as a form of sustenance. After its industrialization, the battle between the manufacturers and the neighborhood bakeries over consumers began. With manufacturers, such as Wonder Bread, trying to maximize profits and dominate the market, corporate leaders aimed to discourage consumers from purchasing from smaller bakeries. -

UV-Treated Baker's Yeast (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae)

Summary of the application: UV-treated baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Applicant: Lallemand Bio-Ingredients Division, 1620 Prefontaine Street, Montreal, Quebec, H1W2N8, Canada The Novel Food subject to this application is UV-treated baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is treated with ultraviolet light to induce the conversion of ergosterol to vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Vitamin D2 content in the yeast concentrate varies between 800 000-3 500 000 IU vitamin D/100 g (200-875 μg/g). The yeast may be inactivated. The yeast concentrate is blended with regular baker's yeast in order not to exceed the maximum level in the pre- packed fresh or dry yeast for home baking. Tan-coloured, free-flowing granules. In 2014, Lallemand obtained the authorization to place the UV-treated baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) on the market as a novel food. In fact, in December 2013, EFSA concluded that the UV- treated baker’s yeast is safe under the intended conditions of use (EFSA NDA Panel, 2014). The UV- treated baker’s yeast was approved for use in the production of yeast-leavened bread and rolls, yeast- leavened fine bakery wares and food supplements as per Annex I of the Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2014/396. An extension of use was authorised in 2018 by the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1018 following a request by Lallemand. Lallemand, through its division Lallemand Bio-Ingredients, located at 1620 Prefontaine Street, H1W 2N8, Montréal, QC (Canada), is hereby requesting for an extension of use of the UV-treated baker’s yeast as a novel food, as Lallemand intends to use the novel food in additional food categories. -

Flour Portfolio

Overview CODE DESCRIPTION PACK ENRICHED UNBLEACHED UNTREATED Ardent Mills Flour Classification ALL PURPOSE FLOUR Hard Wheat Flour 10089 BAKER’S HAND™ All Purpose Flour 20 kg ü Includes all purpose, strong bakers, whole wheat and pizza flour. ™ Flour Portfolio 10082 BAKER’S HAND All Purpose Flour 20 kg ü ü • Protein range from 11.5% to 14%+ 10112 BAKER’S HAND™ Select All Purpose Flour 20 kg ü ü • Primarily used to bake yeast leavened products 10093 Hotel & Restaurant Flour 10 kg ü 10095 Hotel & Restaurant Flour 10kg ü ü Soft Wheat Flour STRONG BAKERS FLOUR Includes cake and pastry flour. Ideal for delicate cakes, pastries and baked goods. ® • Protein range from 7% to 10% 10495 KEYNOTE Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg ü ® ü ü • Primarily used to bake non-yeast leavened products 10496 KEYNOTE Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg 10586 KEYNOTE® UT Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg ü ü Durum 10597 Super KEYNOTE® Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg ü Includes durum semolina and durum flour. 10483 KEYNOTE® Select Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg ü • Protein range 13%+ 10457 KEYNOTE® Select Strong Bakers Flour 20 kg ü ü • Used to make noodles, pasta and ethnic flat breads 10422 RAPIDO® No-time Dough Flour 20 kg ü 10421 RAPIDO® No-time Dough Flour 20 kg ü ü PIZZA FLOUR 10063 Pizza Flour 20 kg ü ü The Kernel of Wheat 10134 Primo Mulino™ Neapolitan Style Pizza Flour 20 kg ü ü Bran WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR • Bran is the hard, brownish outer protective skin of the grain. It surrounds 10030 ALL-O-WHEAT ™ Whole Wheat Flour 20 kg the germ and the endosperm, protecting the grain from weather, insects, 10023 ALL-O-WHEAT ™ Coarse Whole Wheat Flour 20 kg and mold. -

100% ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR 100% Employee Owned

Try it once. Trust it always. MILLED FROM SELECT 100% AMERICAN WHEAT We’re America’s oldest flour company, made up of passionate bakers committed to spreading the joy of baking. That’s why we 08100_6_3_1_0615 take such care with our flour. Unbleached and unblemished by WE BELIEVE chemicals, our flour is the professional’s choice and the home baked goods and doing baker’s trusted partner, prized for its consistent quality. As essential as good flour is to good results, for us, it’s still only good go hand in hand. the beginning. We offer many kinds of help, so bakers of all kinds can bake with joy. At King Arthur Flour, we care as much about our people, our community, We’re here to help. and our planet as we do about our flour. Through % for the Planet (onepercentfortheplanet.org) we donate RECIPES FLOURISH OUR BLOG one percent of sales from this flour to Find tried-and-truly-good recipes select environmental nonprofits. Great recipes, helpful tips, kitchen using our premium Whole Wheat Flour We are a -percent employee-owned stories. And always, the joy of baking. company of passionate bakers, and a at KingArthurFlour.com/recipes. KingArthurFlour.com/blog founding B Corporation, committed to the highest quality and the greater good. BAKER’S STORE BAKER’S HOTLINE INGREDIENTS: CERTIFIED 100% ORGANIC HARD RED WHEAT. Discover our wide array of quality Call or chat online with our ingredients, kitchen tools, and more. friendly, experienced bakers. KingArthurFlour.com . .BAKE ( ) 100% ORGANIC DISTRIBUTED BY THE KING ARTHUR FLOUR COMPANY, INC. -

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS for MILLS and FLAKERS for More Than 30 Years

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS FOR MILLS AND FLAKERS For more than 30 years We would like to thank you and are glad that you have decided to purchase a product from our company. You will enjoy your solid device for a long time, since it has been produced by hand with an impressive love for the detail from best materials. Please thoroughly read these operating instructions before using the device for the first time. There you will find all information for a safe operation. We wish you to enjoy preparing your fine dishes Marcel and Peter Koidl 2 3 Safety instructions for KoMo devices 1. Please thoroughly read the operating 6. Our devices are engineered for grinding of normal instructions and follow the included notes. household quantities of corn to flour, flakes and grist and it is not intended for commercial use. The exception are our professional devices. 2. Connect your electrical device only to a suitable power socket. Check if the data which are indicated on type plate comply with your power grid. Do not use any 7. They must only be operated by adults who multiple plugs or extension cables. are physically and mentally able to operate the devices and who have completely read these instructions. 3. Only use the device if all associated parts are in perfect condition. 8. Switch your device off when it is no longer used. 4. Only use purified raw food. Non-purified raw food 9. Before opening the device the power line often contains small stones and impurities, which might must always be disconnected! Risk of injury by damage the device.