Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/25/2021 10:27:51AM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

ANTI-APARTHEID ANTI-APARTHEID MOVEMENT annual report Of activities and developments october 1979 september 1980 - 7- ' -- - - " -,-I ANTI-APARTHEID MOVEMENT Annual Report 1979 October 1979 - September 1980 Hon President Bishop Ambrose Reeves Vice Presidents Bishop Trevor Huddleston CR Jack Jones CH Joan Lestor MP Rt Hon Jeremy Thorpe MP Sponsors Lord Brockway Basil Davidson Thomas Hodgkin Rt Hon David Steel MP Pauline Webb Chairman Bob Hughes MP Joint Vice Chairmen Ethel de Keyser Simon Hebditch Joint Hon Treasurers Tony O'Dowd Rod Pritchard Hon Secretary Abdul S Minty Staff Chris Child Cate Clark Sue Longbottom Charlotte Sayer (to February/March 1980) David Smith Mike Terry Editor, Anti-Apartheid News Christable Gurney (to January 1980) Pat Wheeler (January-March 1980) Typesetting, design, etc Nancy White CONTENTS Introduction Zimbabwe Southern Africa after Zimbabwe Namibia South Africa Campaigns: Southern Africa-The Imprisoned Society Military and nuclear collaboration Economic collaboration Sports boycott Cultural and academic boycott Material aid International work Areas of work: Local groups Trade unions Youth and students Schools Parliament Women Black community Political parties Health Information: Anti-Apartheid News Publications Services The Media Finance and fund-raising Organisation BISHOP AMBROSE REEVES In December 1979, Bishop Ambrose Reeves, President of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, celebrated his eightieth birthday. To mark the occasion, the AAM organised a special meeting in London, which heard speeches and messages from distinguished leaders around the world, including tributes from the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Secretary-General of the United Nations and the President of the African National Congress, Oliver Tambo. Bishop Reeves' contribution, said Mr Tambo, had been such that it made him one of the 'great giants' of the struggle for freedom in Southern Africa. -

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I–XV

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I–XV ABBOTTS, William (1873–1930) I ALLEN, Sir Thomas William (1864–1943) I ABLETT, Noah (1883–1935) III ALLINSON, John (1812/13–1872) II ABRAHAM, William (Mabon) (1842–1922) I ALLSOP, Thomas (1795–1880) VIII ACLAND, Alice Sophia (1849–1935) I AMMON, Charles (Charlie) George (1st ACLAND, Sir Arthur Herbert Dyke (1847– Baron Ammon of Camberwell) (1873– 1926) I 1960) I ADAIR, John (1872–1950) II ANCRUM, James (1899–1946) XIV ADAMS, David (1871–1943) IV ANDERSON, Frank (1889–1959) I ADAMS, Francis William Lauderdale (1862– ANDERSON, William Crawford (1877–1919) 1893) V II ADAMS, John Jackson (1st Baron Adams of ANDREWS Elizabeth (1882–1960) XI Ennerdale) (1890–1960) I APPLEGARTH, Robert (1834–1924) II ADAMS, Mary Jane Bridges (1855–1939) VI ARCH, Joseph (1826–1919) I ADAMS, William Edwin (1832–1906) VII ARMSTRONG, William John (1870–1950) V ADAMS, William Thomas (1884–1949) I ARNOLD, Alice (1881–1955) IV ADAMSON, Janet (Jennie) Laurel (1882– ARNOLD, Thomas George (1866–1944) I 1962) IV ARNOTT, John (1871–1942) X ADAMSON, William (1863–1936) VII ASHTON, Thomas (1841–1919) VII ADAMSON, William (Billy) Murdoch (1881– ASHTON, Thomas (1844–1927) I 1945) V ASHTON, William (1806–1877) III ADDERLEY, The Hon. James Granville ASHWORTH, Samuel (1825–1871) I (1861–1942) IX ASKEW, Francies (1855–1940) III AINLEY, Theodore (Ted) (1903–1968) X ASPINWALL, Thomas (1846–1901) I AITCHISON, Craigie (Lord Aitchison) ARTHUR James (1791–1877) XV (1882–1941) XII ATKINSON, Hinley (1891–1977) VI AITKEN, William (1814?–1969) X AUCOTT, -

This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ 1 ‘Images of Labour: The Progression and Politics of Party Campaigning in Britain’ By Dominic Wring Abstract: This paper looks at the continuities and changes in the nature of election campaigns in Britain since 1900 by focusing on the way campaigning has changed and become more professional and marketing driven. The piece discusses the ramifications of these developments in relation to the Labour party's ideological response to mass communication and the role now played by external media in the internal affairs of this organisation. The paper also seeks to assess how campaigns have historically developed in a country with an almost continuous, century long cycle of elections. Keywords: Political marketing, British elections, Labour Party, historical campaigning, party organisation, campaign professionals. Dominic Wring is Programme Director and Lecturer in Communication and Media Studies at Loughborough University. He is also Associate Editor (Europe) of this journal. Dr Wring is especially interested in the historical development of political marketing and has published on this in various periodicals including the British Parties and Elections Review, European Journal of Marketing and Journal of Marketing Management. 2 Introduction. To paraphrase former General Secretary Morgan Philips’ famous quote, Labour arguably owes more to marketing than it does to Methodism or Marxism. -

Power As Well As Persuasion: Political Communication and Party Development

Loughborough University Institutional Repository Power as well as Persuasion: political communication and Party development This item was submitted to Loughborough University's Institutional Repository by the/an author. Citation: WRING, D., 2001. Power as well as Persuasion: political commu- nication and Party development. IN: Bartle, J. & Griffiths, D.(eds.) Political Communication Transformed, Hampshire: Macmillan-Palgrave Additional Information: • This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been reviewed or edited. The definitive version of this extract may be found in the work, Political Communication Transformed by Bartle and Griffiths, which can be purchased from www.palgrave.com. Metadata Record: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/1093 Publisher: c Palgrave-Macmillan Please cite the published version. This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ 1 Wring, D.(2001) 'Power as well as Persuasion: Political Communication and Party Development', in Bartle, J. & Griffiths, D.(eds.) Political Communication Transformed, Hampshire: Macmillan-Palgrave. 2 Power as well as Persuasion: Political Communication and Party Development. Dominic Wring Introduction. In the run-up to and during the 1997 general election political discourse was dominated by references to the supposed power and influence of the so-called 'spin doctors' and 'image makers'. These terms are often, and quite erroneously, used interchangeably. Those charged with 'doctoring' the 'spin' are primarily concerned with managing so-called 'free' media which is the coverage given politicians by print and broadcast journalists. -

Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision Marcia Marie Lewandowski College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Lewandowski, Marcia Marie, "Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625615. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4w70-3c60 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRITAIN'S LABOUR PARTY AND THE EEC DECISION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Marcia Lewandowski 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Marcia Marie Lewandowski Approved, May 1990 Alan J. Ward Donald J. B Clayton M. Clemens TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. .............. iv ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Anti-Apartheid Anti-Apartheid Movement Annual Report of Activities and Developments October1975 September1976 44 -_ AntiApartheid Movement ANNUAL REPORT October 1975 - September 1976 Hon President: BISHOP AMBROSE REEVES Vice Presidents: JACK JONES MBE BISHOP TREVOR HUDDLESTON CR JOAN LESTOR MP RT HON JEREMY THORPE MP Sponsors: LORD BROCKWAY LORD COLLISON BASI L DAVI DSON THOMAS HODGKIN RT HON REG PRENTICE MP DAVID STEEL MP ANGUS WILSON Chairman: JOHN ENNALS Vice Chairman: BOB HUGHES MP Hon Treasurer: TONY O'DOWD Hon Secretary: ABDUL S MINTY Staff: SHEILA ALLEN (Clerical Secretary) CHRIS CHILD (Field Officer) BETTY NORTHEDGE (Membership Secretary) YVONNE STRACHAN (Field Officer) MIKE TERRY (Executive Secretary) NANCY WHITE (Assistant Secretary) Editor, Anti-Apartheid News: CHRISTABEL GURNEY Contents Introduction Campaigns: Soweto Military Collaboration BOSS Angola: South Africa's aggression Bantustans Investment and Trade Emigration and Tourism Women Under Apartheid Southern Africa-The Imprisoned Society Namibia Zimbabwe/Rhodesia Sports Boycott Cultural Boycott International Work Organisation: Membership Annual General Meeting National Committee Executive Committee AAM Office Areas of Work: Trade Union Movement Student Work Local Activity Political Parties Parliament Schools Information: Anti-Apartheid News Media Speakers Publications Finance and Fund raising Published by the Anti-Apartheid Movement 89 Charlotte Street London WI P 2DQ Tel 01-580 5311 Foreword The Annual Report of the Anti-Apartheid Movement describes the activities in which we have been engaged during the last twelve months and says something of our hopes for the future. Behind this record lies the devoted services of the members of the staff without which our continuing resolute opposition to apartheid would have been impossible. -

FABIAN REVIEW the Quarterly Magazine of the Fabian Society Summer 2020 / Fabians.Org.Uk / £4.95 LEADING the CHARGE

FABIAN REVIEW The quarterly magazine of the Fabian Society Summer 2020 / fabians.org.uk / £4.95 LEADING THE CHARGE Building a better world: Glen O’Hara on leadership, Lisa Nandy MP on Britain’s global role and Lynne Segal and Jo Littler on the politics of caring p10 / Liam Byrne MP brings a message of compassion p16 / Kevin Kennedy Ryan traces the power of the Labour poster p19 Fabian membership + donation For members who are in a position to give more to the society we offer three tiers of membership plus donation: COLE membership plus donation – £10 / month All the benefits of standard membership plus: a Fabian Society branded canvas bag; a free ticket to either our new year or summer conference; invitation to an annual drinks reception; and regular personal updates from the general secretary. CROSLAND membership plus donation – £25 / month All the benefits of COLE plus: free tickets to all Fabian events; a printed copy of every Fabian report, sent to your home; and invitations to political breakfasts with leading figures on the left. WEBB membership plus donation – £50 / month All the benefits of CROSLAND plus: regular personal updates from leading Fabian parliamentarians; an annual dinner with the general secretary and Fabian parliamentarians; and special acknowledgement as a patron in our annual report and on our website. For more information & to donate visit fabians.org.uk/donate Contents FABIAN REVIEW Volume 132—No. 2 Leader Andrew Harrop 4 The next step Shortcuts Jermain Jackman 5 A black British renaissance Daniel Zeichner MP -

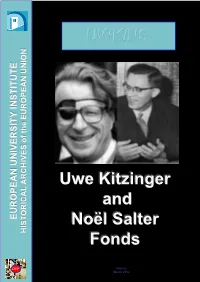

Fonds Inventory

UWK/NS Uwe Kitzinger and EUROPEAN INSTITUTEUNIVERSITY Noël Salter HISTORICAL ARCHIVES of the EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN the of ARCHIVES HISTORICAL Fonds DEP Firenze March 2012 Uwe Kitzinger and Noël Salter Fonds Table of contents UWK-NS Uwe Kitzinger and Noël Salter Fonds _______________________________5 UWK-NS.A Uwe Kitzinger ____________________________________________8 UWK-NS.A-1 Europe, Britain and the Common Market __________________________ 8 UWK-NS.A-1.1 British Entry to EEC _________________________________________ 8 UWK-NS.A-1.2 Re-negotiation of Accession Treaty ____________________________ 14 UWK-NS.A-1.3 Enlargement _____________________________________________ 16 UWK-NS.A-1.4 Working Papers ___________________________________________ 16 UWK-NS.A-1.5 General _________________________________________________ 18 UWK-NS.A-2 Cabinet of Sir Christopher Soames ______________________________ 19 UWK-NS.A-2.1 Office of Sir Christopher Soames _____________________________ 20 UWK-NS.A-2.2 Speeches ________________________________________________ 23 UWK-NS.A-2.3 Advisor in the Soames' Cabinet _______________________________ 25 UWK-NS.A-2.4 Visits ___________________________________________________ 26 UWK-NS.A-2.5 International Organisations and Associations ____________________ 27 UWK-NS.A-3 Media, Books and Publishing ___________________________________ 28 UWK-NS.A-3.1 Germany ________________________________________________ 28 UWK-NS.A-3.2 Common Market __________________________________________ 31 UWK-NS.A-3.3 Journal of Common Market -

Title: the Response of the Labour Government to the “Revolution of Carnations” in Portugal, 1974-76

1 Title: The Response of the Labour Government to the “Revolution of Carnations” in Portugal, 1974-76 Name: Simon Cooke Institution: UCL Degree: PhD History 2 I, Simon Justin Cooke confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis examines the response of the Labour Government to events in Portugal following the coup d’état in April 1974. Britain, as Portugal’s traditional ally and largest trading partner, with close partisan ties between the Labour movement and Portuguese Socialist Party, was a leading player in the international response to developments in Lisbon. The Portuguese Revolution also had wider implications for British foreign policy: the presence of communist ministers in government threatened both the cohesion of NATO and detente with the Soviet Union; West European leaders sought to influence events in Lisbon through the new political structures of the EEC; the outcome of events in Portugal appeared to foreshadow a political transition in Spain; and decolonisation in Angola and Mozambique made Rhodesia’s continued independence unlikely. This study therefore contributes to historical debate concerning the Labour Government and its foreign policy during the 1970s. It considers the extent to which the domestic, political and economic difficulties of the Labour Government during this period undermined the effectiveness of its foreign policy. This thesis also considers the relative importance of, and interplay between, the factors which shaped post-war British foreign policy: the Cold War, membership of NATO and the EEC; relations with newly independent states in the developing world and the Commonwealth; and the relationship with the United States. -

Labour's 'Broad Church'

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES REACTION AND RENEWAL – LABOUR’S ‘BROAD CHURCH’ IN THE CONTEXT OF THE BREAKAWAY OF THE SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY 1979-1988 PAUL BLOOMFIELD A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted: November 2017 Acknowledgements There are many people that I would like to thank for their help in the preparation of this thesis. I would like to thank first of all for their supervision and help with my research, my PhD Supervisory team of Dr Jonathan Davis and Professor Rohan McWilliam. Their patience, guidance, exacting thoroughness yet good humour have been greatly appreciated during the long gestation of this research work. For their kind acceptance in participating in the interviews that appear in this thesis, I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to former councillor and leader of Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council John Battye, Steve Garry and former councillor Jeremy Sutcliffe; the Right Honourable the Lord Bryan Davies of Oldham PC; the Right Honourable Frank Dobson MP; Labour activist Eddie Dougall; Baroness Joyce Gould of Potternewton; the Right Honourable the Baroness Dianne Hayter of Kentish Town; the Right Honourable the Lord Neil Kinnock of Bedwelty PC; Paul McHugh; Austin Mitchell MP; the Right Honourable the Lord Giles Radice PC; the Right Honourable the Lord Clive Soley of Hammersmith PC; and the Right Honourable Baroness Williams of Crosby. For their help and assistance I would like to thank the staff at the Labour History Archive and Study Centre, People’s History Museum, Central Manchester, Greater Manchester; the staff at the Neil Kinnock Archives, Churchill College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge; and the staff at the David Owen Archives, University of Liverpool, Special Collections and Archives Centre, Liverpool. -

Rethinking Revisionist Social Democracy: the Case of the Manifesto Group and Labour's 1970S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Rethinking Revisionist Social Democracy: The Case of the Manifesto Group and Labour’s 1970s ‘Third Way’ Stephen Meredith University of Central Lancashire The Manifesto Group of centre-right Labour MPs was established in December 1974 to combat the growing organizational strength and success of the left-wing Tribune Group in elections to Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) offi ce, and to buttress the 1974 Labour government against the general advance of the left within the party. It was also an attempt to respond to the emerging incoherence of the personnel and programme of revisionist social democracy and to attempt to organize the centre-right of the PLP under a single banner. In policy terms, it concerned itself inevi- tably with analysis of economic and industrial policy, both as a critique of the perceived limitations of Labour’s attachment to conventional tools of Keynesian social democratic political economy as it crumbled in the 1970s and as a ‘moderate’ social democratic ‘third way’ response to the emerging alternatives of the Labour left’s Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) and the neo-liberalism of the New Right. Much of the meaning and impact of Manifesto Group ideas and proposals were lost in the context and clamour of economic crisis and polarized political divisions of the time. With recent claims of adherence to ideas and politics that claim to chart a ‘third way’ course through the mire of discrete and outmoded ideologies, emerging themes, ideas, and proposals of the Manifesto Group retrospectively possess greater resonance for analysis of the subsequent development of social democracy and social democratic political economy and emer- gence of ‘New’ Labour. -

Fielding Prelims.P65 1 10/10/03, 12:29 the LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70

fielding jkt 10/10/03 2:18 PM Page 1 The Volume 1 Labour andculturalchange The LabourGovernments1964–1970 The Volume 1 Labour Governments Labour Governments 1964–1970 1964–1970 This book is the first in the new three volume set The Labour Governments 1964–70 and concentrates on Britain’s domestic policy during Harold Wilson’s tenure as Prime Minister. In particular the book deals with how the Labour government and Labour party as a whole tried to come to Labour terms with the 1960s cultural revolution. It is grounded in Volume 2 original research that uniquely takes account of responses from Labour’s grass roots and from Wilson’s ministerial colleagues, to construct a total history of the party at this and cultural critical moment in history. Steven Fielding situates Labour in its wider cultural context and focuses on how the party approached issues such as change the apparent transformation of the class structure, the changing place of women, rising black immigration, the widening generation gap and increasing calls for direct participation in politics. The book will be of interest to all those concerned with the Steven Fielding development of contemporary British politics and society as well as those researching the 1960s. Together with the other books in the series, on international policy and Fielding economic policy, it provides an unrivalled insight into the development of Britain under Harold Wilson’s premiership. Steven Fielding is a Professor in the School of Politics and Contemporary History at the University of Salford MANCHESTER MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 volume 1 fielding prelims.P65 1 10/10/03, 12:29 THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 Series editors Steven Fielding and John W.