Wissenschaftliches Seminar Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Shakespeare, Madness, and Music

45 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page i Shakespeare, Madness, and Music Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations Kendra Preston Leonard THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 46 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page ii Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Kendra Preston Leonard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Leonard, Kendra Preston. Shakespeare, madness, and music : scoring insanity in cinematic adaptations, 2009. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-6946-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-6958-5 (ebook) 1. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616—Film and video adaptations. 2. Mental illness in motion pictures. 3. Mental illness in literature. I. Title. ML80.S5.L43 2009 781.5'42—dc22 2009014208 ™ ϱ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS the Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-Upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BH

www.rsc.org.uk +44 1789 294810 Fax: +44 1789 296655 Tel: 6BH CV37 Warwickshire Stratford-upon-Avon Southern Lane Theatre The Courtyard Company Shakespeare Royal ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2006 2007 2006 2007 131st REPORT CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 03 OF THE BOARD To be submitted to the Annual ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT 04 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 14 December EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT 07 2007. To the Governors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is ACHIEVEMENTS 08 – 09 hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard VOICES 10 – 33 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 14 December 2007 FINANCIAL REVIEW OF THE YEAR 34 – 37 commencing at 2.00pm, to consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial SUMMARY ACCOUNTS 38 – 41 Activities and the Balance Sheet of the Corporation at 31 March 2007, to elect the Board for the SUPPORTING OUR WORK 42 – 43 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be trans- AUDIENCE REACH 44 – 45 acted at the Annual General Meetings of the Royal Shakespeare Company. YEAR IN PERFORMANCE 46 – 51 By order of the Board ACTING COMPANIES 52 – 55 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors THE COMPANY 56 – 57 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 58 ASSOCIATES/ADVISORS 59 CONSTITUTION 60 Right: Kneehigh Theatre perform Cymbeline photo: xxxxxxxxxxxxx Harriet Walter plays Cleopatra This has been a glorious year, which brought together the epic and the personal in ways we never anticipated when we set out to stage every one of Shakespeare’s plays, sonnets and long poems between April 2006 and April 2007. -

“Hosing Off the Heraldry”: Critical Reactions to Shakespeare's History

“Hosing Off the Heraldry”: Critical Reactions to Shakespeare’s History Plays at Stratford. Roy Pierce-Jones During the summer of 1901, Frank Benson and his company of young actors performed, in the space of a single week, six of Shakespeare’s history plays at the Memorial Theatre, Stratford Upon Avon. The ‘Week of Kings’, as it came to be called, was given chronologically by reign, but with neither of the ‘tetrologies’ having been preserved in their entirety. King John was followed by Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI and finally, Richard III. W.B. Yeats, visiting Stratford that summer, welcomed the opportunity of seeing these plays performed in sequence “because of the way play supports play’. The experience had a profound effect on him – ‘The theatre has moved me as it has never done before’. (142- 43) Over the next hundred years, Shakespeare’s histories were to appear regularly on the Stratford stage; sometimes at what seemed the crucial defining moments in the history of Shakespearian performance in the English theatre. By looking at the initial reception to these royal marathons, one gains something of an insight, not only into what was valued or rejected by the critics of the day, but we might consider whether these most nationalistic plays offered a commentary on our shared sense of our history. If Shakespeare was our contemporary, what was he saying to us? Whilst individual history plays have always proved popular on the Stratford stage, Richard III and Henry V in particular, it wasn’t until Anthony Quayle staged a cycle of the English Histories, as part of the festival of Britain celebrations in 1951, that we have a discernible commentary relating to an ideological context informing the productions. -

The Second Part of King Henry IV William Shakespeare , Edited by Giorgio Melchiori , with Contributions by Adam Hansen Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86926-3 — The Second Part of King Henry IV William Shakespeare , Edited by Giorgio Melchiori , With contributions by Adam Hansen Frontmatter More Information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE Brian Gibbons A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. From to the General Editor was Brian Gibbons and the Associate General Editors were A. R. Braunmuller and Robin Hood. THE SECOND PART OF KING HENRY IV Giorgio Melchiori offers a fresh approach to the text of The Second Part of King Henry IV, which he sees as an unplanned sequel to the First Part, itself a ‘remake’ of an old, non- Shakespearean play. The Second Part deliberately exploits the popular success of Sir John Falstaff, introduced in Part One; the resulting rich humour gives a comic dimension to the play which makes it a unique blend of history, Morality play and comedy. Among modern editions of the play this is the one most firmly based on the quarto. It presents an eminently actable text, by showing how Shakespeare’s own choices are superior for practical purposes to suggested emendations, and by keeping interference in the original stage directions to a minimum, in order to respect, as Shakespeare did, the players’ freedom. This updated edition includes a new introductory section by Adam Hansen describing recent stage, film and critical interpretations. -

37 Plays 37 Films 37 Screens

the complete walk 37 PLAYS 37 FILMS 37 SCREENS A celebratory journey through Shakespeare’s plays along the South Bank and Bankside Credits and Synopses shakespearesglobe.com/400 #TheCompleteWalk 1 contents 1 THE TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA 3 20 HENRY V 12 2 HENRY VI, PART 3 3 21 AS YOU LIKE IT 13 3 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW 4 22 JULIUS CAESAR 13 4 HENRY VI, PART 4 23 OTHELLO 14 5 TITUS ANDRONICUS 5 24 MEASURE FOR MEASURE 14 6 HENRY VI, PART 2 5 25 TWELFTH NIGHT 15 7 ROMEO & JULIET 6 26 TROILUS AND CRESSIDA 15 8 RICHARD III 6 27 ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL 16 9 LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST 7 28 TIMON OF ATHENS 16 10 KING JOHN 7 29 ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA 17 11 THE COMEDY OF ERRORS 8 30 KING LEAR 17 12 RICHARD II 8 31 MACBETH 18 13 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM 9 32 CORIOLANUS 18 14 THE MERCHANT OF VENICE 9 33 HENRY VIII 19 15 HENRY IV, PART 1 10 34 PERICLES 19 16 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 10 35 CYMBELINE 20 17 HENRY IV, PART 2 11 36 THE WINTER’S TALE 20 18 THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR 11 37 THE TEMPEST 21 19 HAMLET 12 2 THE TWO GENTLEMEN HENRY VI, PART 3 OF VERONA Filmed at Towton Battlefield, England Filmed at Scaligero Di Torri Del Benaco, St Thomas’ Hospital Garden Verona, Italy St Thomas’ Hospital Garden CREDITS Father DAVID BURKE CREDITS Son TOM BURKE Julia TAMARA LAWRANCE Henry VI ALEX WALDMANN Lucetta MEERA SYAL Director NICK BAGNALL Director of Photography ALISTAIR LITTLE Director CHRISTOPHER HAYDON Sound Recordist WILL DAVIES Director of Photography IONA FIROUZABADI Sound Recordist JUAN MONTOTO UGARTE ON-STAGE PRODUCTION (GLOBE TO GLOBE FESTIVAL) ON-STAGE PRODUCTION Performed in Macedonian by the National Theatre (GLOBE ON SCREEN) of Bitola, Macedonia A Midsummer Night’s Dream Twelfth Night Director JOHN BLONDELL As You Like It Othello SYNOPSIS Romeo and Juliet As the War of the Roses rages, Richard, Duke of Measure for Measure York, promises King Henry to end his rebellion if his All’s Well That Ends Well sons are named heirs to the throne. -

Exploring the Individuality of Shakespeare's History Plays

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository REWRITING HISTORY: EXPLORING THE INDIVIDUALITY OF SHAKESPEARE’S HISTORY PLAYS by PETER ROBERT ORFORD A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The Shakespeare Institute The University of Birmingham January 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract ‘Rewriting History’ is a reappraisal of Shakespeare’s history cycle, exploring its origins, its popularity and its effects before challenging its dominance on critical and theatrical perceptions of the history plays. A critical history of the cycle shows how external factors such as patriotism, bardolatory, character-focused criticism and the editorial decision of the First Folio are responsible for the cycle, more so than any inherent aspects of the plays. The performance history of the cycle charts the initial innovations made in the twentieth century which have affected our perception of characters and key scenes in the texts. I then argue how the cycle has become increasingly restrictive, lacking innovation and consequently undervaluing the potential of the histories. -

Questioning Bodies in Shakespeare's Rome

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2010, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783899717402 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783862347407 Interfacing Science, Literature, and the Humanities / ACUME 2 Volume 4 Edited by Vita Fortunati, Università di Bologna Elena Agazzi, Università di Bergamo Scientific Board Andrea Battistini (Università di Bologna), Jean Bessière (Université Paris III - Sorbonne Nouvelle), Dino Buzzetti (Università di Bologna), Gilberto Corbellini (Università di Roma »La Sapienza«), Theo D’Haen (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven), Claudio Franceschi (Università di Bologna), Brian Hurwitz (King’s College, London), Moustapha Kassem (Odense Universiteit, Denmark), Tom Kirkwood (University of Newcastle), Ansgar Nünning (Justus Liebig Universität Gießen), Giuliano Pancaldi (Università di Bologna), Manfred Pfister (Freie Universität Berlin), Stefano Poggi (Università di Firenze), Martin Prochazka (Univerzita Karlova v Praze), Maeve Rea (Queen’s College, Belfast), Ewa Sikora (Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology, Warszawa), Paola Spinozzi (Università di Ferrara) Editorial Board Kirsten Dickhaut (Justus Liebig Universität Gießen), Raul Calzoni (Università di Bergamo), Gilberta Golinelli (Università di Bologna), Andrea Grignolio (Università di Bologna), Pierfrancesco Lostia (Università di Bologna) Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2010, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783899717402 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783862347407 Maria Del Sapio Garbero / Nancy Isenberg / Maddalena Pennacchia (eds.) Questioning Bodies in Shakespeare's Rome With 19 figures V&R unipress Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 © 2010, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783899717402 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783862347407 This book has been published with the support of the Socrates Erasmus program for Thematic Net- work Projects through grant 227942-CP-1-2006-1-IT-ERASMUS-TN2006-2371/001-001 SO2-23RETH and with the support of the Department of Comparative Literatures, Roma Tre University. -

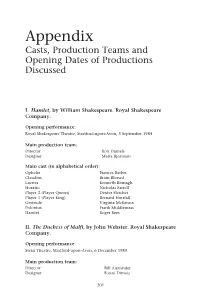

Appendix Casts, Production Teams and Opening Dates of Productions Discussed

Appendix Casts, Production Teams and Opening Dates of Productions Discussed I. Hamlet, by William Shakespeare. Royal Shakespeare Company. Opening performance: Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 5 September 1984 Main production team: Director Ron Daniels Designer Maria Bjornson Main cast (in alphabetical order): Ophelia Frances Barber Claudius Brian Blessed Laertes Kenneth Branagh Horatio Nicholas Farrell Player 2 (Player Queen) Dexter Fletcher Player 1 (Player King) Bernard Horsfall Gertrude Virginia McKenna Polonius Frank Middlemass Hamlet Roger Rees II. The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster. Royal Shakespeare Company. Opening performance: Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 6 December 1989 Main production team: Director Bill Alexander Designer Fotini Dimou 201 202 Appendix Main cast (in alphabetical order): Duke Ferdinand Bruce Alexander The Cardinal Russell Dixon Cariola Sally Edwards Antonio Bologna Mick Ford Julia Patricia Kerrigan Daniel de Bosola Nigel Terry The Duchess of Malfi Harriet Walter III. The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster. Cheek By Jowl. Opening performances: Bury St. Edmunds, 19 September 1995 Wyndham’s Theatre, London, 2 January 1996 Main production team: Director Declan Donnellan Designer Nick Ormerod Main cast (in alphabetical order): Daniel de Bosola George Anton The Cardinal Paul Brennen Cariola Avril Clark Duke Ferdinand Scott Handy The Duchess of Malfi Anastasia Hille Antonio Bologna Matthew Macfadyen Julia Nicola Redmond IV. Titus, based on Titus Andronicus, by William Shakespeare. Motion Picture. -

William Houston

VAT No. 993 055 789 WILLIAM HOUSTON TRAINED: CENTRAL SCHOOL OF SPEECH AND DRAMA Film: Level Up The Business Man Fullwell 73 Ltd Adam Randall Dracula Untold Cazan Legendary Pictures Gary Shore Son Of God Moses Hearst Entertainment Productions Christopher Spencer Sawney: Flesh Of Man Charlie Mcguire TVP Film & Multimedia Ricky Wood Age Of Heroes Sgt MacKenzie Giant Films Adrian Vitoria Sherlock Holmes 2 Constable Clark Warner Bros. Guy Ritchie Clash Of The Titans Ammon Warnor Bros. Louis Leterrier Sherlock Holmes Constable Clark Warner Bros. Guy Ritchie Fifty Dead Men Walking Ray Brightlight Pictures Kari Skogland Elizabeth: The Golden Age Don Guerau Universal Pictures Shekhar Kapur Puffball Tucker Dan Films Nick Roeg The Odyssey Anticlus Hallmark Andrei Konchalovsky The Gambler Pasha Canal+ Karolly Maak Surviving Picasso Casagemas Merchant Ivory James Ivory Hamlet Hamlet Lamancha Prods. Michael Mundell Television: The Watcher DSI Fielder UFA Fiction Ltd Andreas Herzog The Last Trace DSI Fielder UFA Fiction Ltd Andreas Herzog Indian Doctor Basil Thomas Contact Returns Lee Haven Jones Endeavour Richard Broom ITV Craig Viveiros The Bible Moses Lightworkers Media Tony Mitchell Robin Hood Finn BBC Douglas Mackinnon Casualty 1909 Milais Culpin BBC Bryn Higgins Casualty 1907 Milais Culpin BBC Bryn Higgin Lewis George Stoker Granada Dan Reed North & South John Boucher BBC Brian Percival Henry Viii Thomas Seymour Granada Peter Trevis The Bill David Ashe Talkback Thames Kate Cheeseman Theatre: The Iliad Narrator Almeida Theatre Ruper Goold / Robert Icke Titus Andronicus Titus Andronicus Shakespeare's Globe Lucy Bailey Fortune's Fool Kuzovkin The Old Vic Lucy Bailey Three Sisters Vershinin Young Vic Theatre Company Benedict Andrews William Houston 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Millar Court, 43 Station Road, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 1JD Registered in England N0. -

William Houston

WILLIAM HOUSTON Film: Brimstone Eli Martin Koolhoven N279 Entertainment The Dancer Rud Stephanie Di Giusto Les Productions Du Tresor Level Up The Business Man Adam Randall Fullwell 73 Ltd Dracula Untold Cazan Gary Shore Legendary Pictures Son Of God Moses Christopher Spencer Hearst Entertainment Productions Lord Of Darkness Charlie Mcguire Ricky Wood TVP Film & Multimedia Age Of Heroes Sgt. MacKenzie Adrian Vitoria Giant Films Sherlock Holmes 2 Constable Clark Guy Ritchie Warner Bros. Clash Of The Titans Ammon Louis Leterrier Warnor Bros. Sherlock Holmes Constable Clark Guy Ritchie Warner Bros. Fifty Dead Men Walking Ray Kari Skogland Brightlight Pictures Elizabeth: The Golden Age Don Guerau Shekhar Kapur Universal Pictures Puffball: The Devil's Eyeball Tucker Nick Roeg Dan Films The Gambler Pasha Karolly Maak Canal+ Surviving Picasso Casagemas James Ivory Merchant Ivory Hamlet Hamlet Michael Mundell Lamancha Prods. Television: Will Kemp Shekhar Kapur TNT The Watcher DSI Fielder Andreas Herzogu FA Fiction Ltd The Last Trace DSI Fielder Andreas Herzogu FA Fiction Ltd Indian Doctor Basil Thomas Lee Haven Jones Avatar Productions Endeavour Richard Broom Craig Viveiros ITV The Bible Moses Tony Mitchell Lightworkers Media Robin Hood Finn Douglas Mackinnon BBC Casualty 1909 Milais Culpin Bryn Higgins BBC Casualty 1907 Milais Culpin Bryn Higgins BBC Lewis George Stoker Dan Reed Granada North & South John Boucher Brian Percival BBC The Odyssey Anticlus Andrei Konchalovsky Hallmark Henry V I I I Thomas Seymour Peter Trevi Granada The Bill David -

Artist Development and Training in the Royal Shakespeare Company a Vision for Change in British Theatre Culture

Artist Development and Training in the Royal Shakespeare Company A Vision for Change in British Theatre Culture Volume I Lyn Darnley A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of Royal Holloway College, University of London for the degree of PhD Department of Drama and Theatre Arts Royal Holloway College University of London Egham TW20 OEX March 2013 Declaration of Authorship I, Lyn Darnley, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________________ Date: ________________________________ Contents Volume I Page Abstract ......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One: The Royal Shakespeare Company and Training .............. 16 Chapter Two: Training and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre ............. 38 Chapter Three: Cicely Berry....................................................................... 72 Chapter Four: Training and Ensemble under Adrian Noble .................. 104 Chapter Five: The Pilot Programme December 2003 ............................. 140 Chapter Six: Training for the Comedies Ensemble – 2005 ................... 192 Chapter Seven: The Complete Works Festival 2006-2007 ..................... 234 Chapter Eight: Achievements, Challenges and Moving Forwards ....... 277 Bibliography .............................................................................................