Royal Archaeological Institute Newsletter No August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

Welsh Bulletin

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF THE BRITISH ISLES WELSH BULLETIN Editors: R. D. Pryce & G. Hutchinson No. 76, June 2005 Mibora minima - one oftlle earliest-flow~ring grosses in Wales (see p. 16) (Illustration from Sowerby's 'English Botany') 2 Contents CONTENTS Editorial ....................................................................................................................... ,3 43rd Welsh AGM, & 23rd Exhibition Meeting, 2005 ............................ " ............... ,.... 4 Welsh Field Meetings - 2005 ................................... " .................... " .................. 5 Peter Benoit's anniversary; a correction ............... """"'"'''''''''''''''' ...... "'''''''''' ... 5 An early observation of Ranunculus Iriparlitus DC. ? ............................................... 5 A Week's Brambling in East Pembrokeshire ................. , ....................................... 6 Recording in Caernarfonshire, v.c.49 ................................................................... 8 Note on Meliltis melissophyllum in Pembrokeshire, v.c. 45 ....................................... 10 Lusitanian affinities in Welsh Early Sand-grass? ................................................... 16 Welsh Plant Records - 2003-2004 ........................... " ..... " .............. " ............... 17 PLANTLIFE - WALES NEWSLETTER - 2 ........................ " ......... , ...................... 1 Most back issues of the BSBI Welsh Bulletin are still available on request (originals or photocopies). Please enquire before sending cheque -

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

An Early Medieval Cemetery and Circular Enclosure at Felindre Farchog, North Pembrokeshire

100 Archaeology in Wales 56 AN EARLY MEDIEVAL CEMETERY AND CIRCULAR ENCLOSURE AT FELINDRE FARCHOG, NORTH PEMBROKESHIRE Chris Casswell1 , Rhiannon Comeau2 , and Mike Parker Pearson3 with contributions by Mark Bowden4 , Rebecca Pullen5 , David Field 6, Charlene Steele7 and Kate Welham8 Surveys and excavation were undertaken by the Stones of Stonehenge project in 2014 and 2015 at a site near Felindre Farchog, North Pembrokeshire. The site — a 30m-diameter circular earthwork discovered from the air in 2009 — was investigated for the possibility that it might be a flattened prehistoric burial mound or even the remains of a dismantled stone circle or a small henge. Excavation revealed it to be a circular enclosure and an inhumation cemetery of early medieval type within and around an apparently natural mound. Twenty-one east- west grave cuts were identified, some of which were slate-lined. No human remains have survived in this acidic soil. The only artefact found within a grave was a small blue glass bead likely to date to the early medieval period. The burial ground is likely to date to the period before burial in churchyards became the norm, which could have been as late as the 12th century. Figure 1. The location of the mound near Felindre Farchog (drawn by Rhiannon Comeau) 1 Chris Casswell: DigVentures Ltd, London Located almost 5km east of Newport and 8km south-west 2 Rhiannon Comeau: UCL Institute of Archaeology of Cardigan, this small mound and embanked enclosure 3 Mike Parker Pearson: UCL Institute of Archaeology (Fig. 1), is situated in the valley of the River Nevern at 4 Mark Bowden: Historic England, Swindon NGR SN10213893, some 160m south-east of the village of 5 Rebecca Pullen: Historic England, York Felindre Farchog but on the opposite side of the river in the 6 David Field: Yatesbury, Wiltshire parish of Nevern. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust Report on Activities

Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust Report on activities carried out for Adopt-a-riverbank initiative Funded by Dulverton Trust, (Community Foundation in Wales) 23.10.15 to 1.11.16 3 December 2016 Page 1 of 15 Adopt-A-Riverbank Project 2015/16 The Adopt-A-Riverbank project aimed to get as many people as possible engaged in visiting and monitoring their local riverbank. The project was conceived as an initiative to develop and broaden the activities of Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust, building on projects that the Trust has been involved in over the last few years, such as The Cleddau Trail project, the European Fisheries Fund (EFF) project and the Coed Cymru Nature Fund river restoration project. Plans and funding bids were put together during the Summer of 2015 during the last months of the EFF project in order to create a role and bid for funding that would provide ongoing work for the EFF project staff. In July 2015 PRT applied to the Dulverton Trust (Community Fund in Wales) and also to a number of other funding streams including the Natural Resources Wales, Woodward Trust, Milford Haven Port Authority, Supermarkets 5p bag schemes and other local organisations. The aim was to fund a £40K 2 year project with ambitious targets for numbers of people reached and kilometres of riverbank adopted, and to create a sustainable framework for co-ordination and engagement of PRT’s volunteers. PRT was only successful with one of its funding applications; unfortunately no other funding was secured. The Dulverton Trust (Community Foundation in Wales) kindly awarded PRT £5,000. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Prehistoric Britain What Is Prehistoric?

PREHISTORIC BRITAIN WHAT IS PREHISTORIC? Prehistory is the time before written records began. It begins when the earliest hunter-gatherers came to Britain around 450,000 BC. HOW DO WE KNOW WHAT LIFE WAS LIKE IF THERE ARE NO WRITTEN RECORDS? The things we know about this time period comes from artefacts and monuments that archaeologists have discovered. Prehistory is sometimes referred to as the Stone Age and can be split into three distinct time periods: 1. Stone Age 2. Bronze Age 3. Iron Age During this time period there was immense change. People developed from nomadic hunter-gatherers to highly-organised people capable of erecting monuments which survive today. THE STONE AGE The Stone Age is split into three separate time periods: Old Stone Age Palaeolithic 450,000 BC – 10,000 BC People would have used stone tools- artefacts from this time period are rare and we have no evidence of settlements or monuments. Middle Stone Age Mesolithic 10,000 BC- 14,500BC This period began after the last ice age when Britain became an island. Tools became more complex and there is evidence of hunter- gatherer campsites but these are very rare. New Stone Age Neolithic 4,500 BC- 2,300BC People began to become more settled and we see the beginning of farming in England. Plants and animals became domesticated and we see the first pottery. Monuments have been found at this time and they are called henges. STONE AGE ARTEFACTS Palaeolithic Hand axe found in Stonehenge- Neolithic Hampshire monument Neolithic pots THE BRONZE AGE The Bronze Age spanned from 2,300-700 BC. -

The National Way Point Rally Handbook

75th Anniversary National Way Point Rally The Way Point Handbook 2021 Issue 1.4 Contents Introduction, rules and the photographic competition 3 Anglian Area Way Points 7 North East Area Way Points 18 North Midlands Way Points 28 North West Area Way Points 36 Scotland Area Way Points 51 South East Way Points 58 South Midlands Way Points 67 South West Way Points 80 Wales Area Way Points 92 Close 99 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points Introduction • This booklet represents the combined • We should remain mindful of guidance efforts of over 80 sections in suggesting at all times, checking we comply with on places for us all to visit on bikes. Many going and changing national and local thanks to them for their work in doing rules, for the start, the journey and the this destination when visiting Way Points • Unlike in normal years we have • This booklet is sized at A4 to aid compiled it in hope that all the location printing, page numbers aligned to the will be open as they have previously pdf pages been – we are sorry if they are not but • It is suggested you read the booklet on please do not blame us, blame Covid screen and only print out a few if any • This VMCC 75th Anniversary event is pages out designed to be run under national covid rules that may still in place We hope you enjoy some fine rides during this summer. Best wishes from the Area Reps 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points General -

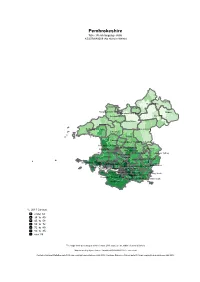

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle.