Yoga-Body-Origins.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico // Rocket Training 60 H Advanced Yoga Teacher Certification with Amber Gean // Rocket Girl Yoga

NEW MEXICO // ROCKET TRAINING 60 H ADVANCED YOGA TEACHER CERTIFICATION WITH AMBER GEAN // ROCKET GIRL YOGA NEXT UPCOMING EVENT Las Cruces, NEW MEXICO May 18th - 22nd, 2017 Hosted by DWELL YOGA What is The Rocket? The Rocket was developed by Larry Schultz in the 1990s while on tour with the Grateful Dead. The Rocket consists of poses from traditional Ashtanga vinyasa yoga. Larry resequenced the poses from first, second, and third series around the joints of the body and the days of the week. By doing this he created a more holistic approach to a regular Ashtanga practice. There are more than 140 poses that your body experiences during one week of consistent Rocket practice. What do you learn in the training? ● Physical Components ● Rocket Routines ○ Bottle Rocket - GREAT FOR BEGINNERS ○ Rocket 1 - Forward bending and core ○ Rocket 2 - Backward bending and arms ○ Rocket 3 - Mixed levels ● Cross Training ● Spotting and Assisting ● Rocket transitions ○ from headstands to arm balances ○ arm balances to handstands ○ mula bandha check up into arm balances ● Learning the “Mechanics of Flight” ○ weight transfer into the hands ○ floating back and forth in the Sun Salutations ○ jump backs from seated postures ○ inversions and handstands from standing postures ○ arm balances and inversions from seated positions ○ creating fluid movement throughout your practice ○ floating with control vs. ballistics ● Fine Tune Your teaching voice and script ● Studying “The System” ○ History of the Rocket ○ 6 day a week practice schedule ○ Larry Schultz Philosophy -

—The History of Hatha Yoga in America: The

“The History of Hatha Yoga in America: the Americanization of Yoga” Book proposal By Ira Israel Although many American yoga teachers invoke the putative legitimacy of the legacy of yoga as a 5000 year old Indian practice, the core of the yoga in America – the “asanas,” or positions – is only around 600 years old. And yoga as a codified 90 minute ritual or sequence is at most only 120 years old. During the period of the Vedas 5000 years ago, yoga consisted of groups of men chanting to the gods around a fire. Thousands of years later during the period of the Upanishads, that ritual of generating heat (“tapas”) became internalized through concentrated breathing and contrary or bipolar positions e.g., reaching the torso upwards while grounding the lower body downwards. The History of Yoga in America is relatively brief yet very complex and in fact, I will argue that what has happened to yoga in America is tantamount to comparing Starbucks to French café life: I call it “The Americanization of Yoga.” For centuries America, the melting pot, has usurped sundry traditions from various cultures; however, there is something unique about the rise of the influence of yoga and Eastern philosophy in America that make it worth analyzing. There are a few main schools of hatha yoga that have evolved in America: Sivananda, Iyengar, Astanga, and later Bikram, Power, and Anusara (the Kundalini lineage will not be addressed in this book because so much has been written about it already). After practicing many of these different “styles” or schools of hatha yoga in New York, North Carolina, Florida, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Paris as well as in Thailand and Indonesia, I became so fascinated by the history and evolution of yoga that I went to the University of California at Santa Barbara to get a Master of Arts Degree in Hinduism and Buddhism which I completed in 1999. -

Przestrzen 1.Pdf

PRZESTR ZEN 2 Wstęp 3 Studia Podyplomowe Technik Relaksacyjnych Stowarzyszenie Trenerów i Praktyków Relaksacji „Przestrzeń” 4 Sztuka utopii Michał Fostowicz-Zahorski 7 Miałki umysł (fragmenty) Renata M. Niemierowska 10 Joga nidra - moje własne doświadczenie, refleksje nad podróżą wewnętrzną Magdalena Kłos 26 Psychosomatyka, czyli somatyka w psychologii Anna Biełous 31 Wielopoziomowe spojrzenie na stres i trening relaksacyjny z perspektywy modelu R. Dilts’a Jacek Borowicz 42 Szkolenie antystresowe dla pracowników na podstawie doświadczeń i obserwacji praktycznych Leszek Jackiewicz, Kinga Truś 49 Dotyk shiatsu jako forma relaksu i zachowania zdrowia Elżbieta Bienias 57 Problemy odnowy psychosomatycznej Piotr Romanek 67 Tai chi, taiji Dariusz Młynarczyk 70 Herbert Benson i jego reakcja relaksacyjna Wanda Rochowska 80 Manadala jako wehikuł dla relaksacji Lesław Kulmatycki 88 Joga dla przedszkolaka Ewa Moroch 97 Kurs dla nauczycieli jogi według tradycji Sivanandy Kornelia Popek 102 Moje Indie z konferencją w tle Lesław Kulmatycki 107 Absolwenci II rocznika studiów 108 Autorzy tego numeru PRZESTRZEŃ 1/2008 mieli pionierzy badań w tej dziedzinie, leka- rze H. Benson i K.R. Pelletier, którzy przed trzydziestu laty tworzyli pierwsze modele SZI NE… teoretyczne tego zjawiska i prowadzili syste- matyczne badania kliniczne. (Zamiast Wstępu) Przypomnijmy krótkie wprowadzenie do systemowej, holistycznej refleksji nad zja- wiskiem relaksacji, jakie zaproponowaliśmy w ubiegłorocznym, „zerowym” numerze „Przestrzeni”: jeśli opisać indywiduum jako system otwarty, pozostający w dynamicznej relacji ze swym środowiskiem, relaksacja jawi się jako samoregulacyjne i zarazem sa- W psychologii systemu introspekcji dzogczen, moorganizacyjne własności tego systemu. wywodzącej się z archaicznej, przedbuddyj- Innymi słowy, indywiduum jako system ot- skiej tradycji tybetańskiej bon, istnieje termin warty dysponuje potencjałem samoregula- szi ne – „ciche spoczywanie w uspokojeniu”. -

Aspectos Científicos Y Beneficiosos Del Culto Tantrico

Scientific and beneficial aspects of tantra cult Ratan Lal Basu Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara Artículos atravesados por (o cuestionando) la idea del sujeto -y su género- como una construcción psicobiológica de la cultura Articles driven by (or questioning) the idea of the subject -and their gender- as a cultural psychobiological construction Vol. 1 (2), 2016 ISSN 2469-0783 https://datahub.io/dataset/2016-1-2-e09 SCIENTIFIC AND BENEFICIAL ASPECTS OF TANTRA CULT ASPECTOS CIENTÍFICOS Y BENEFICIOSOS DEL CULTO TANTRICO Ratan Lal Basu [email protected] Presidency College, Calcutta & University of Calcutta, India. Citation: Basu, R. L. (2016). «Scientific and beneficial aspects of tantra cult». Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 1 (2), 26-49. DOI: 10.32351/rca.v1.2.15 Copyright: © 2016 RCAFMC. This open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-cn) Spain 3.0. Received: 01/04/2016. Accepted: 01/05/2016 Published online: 20/07/2016 Conflicto de intereses: Ninguno que declarar. Abstract This article endeavors to identify and isolate the scientific and beneficial from falsehood, superstition and mysticism surrounding tantrism. Among the various ancient Indian religious and semi-religious practices, tantra cult has got the most widespread recognition and popularity all over the world. The reason for this popularity of tantra has hardly been from academic, spiritual or philosophical interests. On the contrary, it has been associated with promises of achievements of magical and supernatural powers as well as promises of enhancement of sexual power and intensity of sexual enjoyment, and restoration of lost sexual potency of old people. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

HOW STEVE REEVES TRAINED by John Grimek

IRON GAME HISTORY VOL.5No.4&VOL. 6 No. 1 IRON GAME HISTORY ATRON SUBSCRIBERS THE JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL CULTURE P Gordon Anderson Jack Lano VOL. 5 NO. 4 & VOL. 6 NO. 1 Joe Assirati James Lorimer SPECIAL DOUBL E I SSUE John Balik Walt Marcyan Vic Boff Dr. Spencer Maxcy TABLE OF CONTENTS Bill Brewer Don McEachren Bill Clark David Mills 1. John Grimek—The Man . Terry Todd Robert Conciatori Piedmont Design 6. lmmortalizing Grimek. .David Chapman Bruce Conner Terry Robinson 10. My Friend: John C. Grimek. Vic Boff Bob Delmontique Ulf Salvin 12. Our Memories . Pudgy & Les Stockton 4. I Meet The Champ . Siegmund Klein Michael Dennis Jim Sanders 17. The King is Dead . .Alton Eliason Mike D’Angelo Frederick Schutz 19. Life With John. Angela Grimek Lucio Doncel Harry Schwartz 21. Remembering Grimek . .Clarence Bass Dave Draper In Memory of Chuck 26. Ironclad. .Joe Roark 32. l Thought He Was lmmortal. Jim Murray Eifel Antiques Sipes 33. My Thoughts and Reflections. .Ken Rosa Salvatore Franchino Ed Stevens 36. My Visit to Desbonnet . .John Grimek Candy Gaudiani Pudgy & Les Stockton 38. Best of Them All . .Terry Robinson 39. The First Great Bodybuilder . Jim Lorimer Rob Gilbert Frank Stranahan 40. Tribute to a Titan . .Tom Minichiello Fairfax Hackley Al Thomas 42. Grapevine . Staff James Hammill Ted Thompson 48. How Steve Reeves Trained . .John Grimek 50. John Grimek: Master of the Dance. Al Thomas Odd E. Haugen Joe Weider 64. “The Man’s Just Too Strong for Words”. John Fair Norman Komich Harold Zinkin Zabo Koszewski Co-Editors . , . Jan & Terry Todd FELLOWSHIP SUBSCRIBERS Business Manager . -

Führt Der Weg Zum Ziel? Überlegungen Zur Verbindung Des Modernen Yoga*) Mit Patanjalis Yoga-Sutra Annette Blühdorn

erschienen in zwei Teilen in: Deutsches Yoga-Forum 6/2019, S.30-33 und 1/2020, S.26-31 © Dr. Annette Blühdorn Führt der Weg zum Ziel? Überlegungen zur Verbindung des Modernen Yoga*) mit Patanjalis Yoga-Sutra Annette Blühdorn Er hatte es schon in sich erfahren, dass Glaube und Zweifel zusammengehören, dass sie einander bedingen wie Ein- und Ausatmen. (Hermann Hesse, Das Glasperlenspiel) Als im Juni 2015 zum ersten Mal weltweit der Internationale Yoga-Tag begangen wurde, traten sehr schnell Kritiker auf den Plan, die dieses Ereignis als politische Machtdemonstration der national- konservativen indischen Regierung interpretierten. Yoga solle hier als ausschließlich indisches Erbe und Kulturgut dargestellt werden, während doch tatsächlich der heute überall auf der Welt praktizierte moderne Yoga auch von vielfältigen Strömungen und Einflüssen des Westens geprägt worden sei. So ungefähr lautete damals die Kritik, die mir geradezu ketzerisch erschien; ziemlich heftig wurde da an den Grundfesten meiner heilen Yoga-Welt gerüttelt. Weil aber, wie Hermann Hesse im Glasperlenspiel erklärt, Glaube und Zweifel sich gegenseitig bedingen, wurde es mir bald ein Bedürfnis, mich mit dieser Kritik konstruktiv auseinanderzusetzen. Inzwischen sind die Inhalte dieses Forschungszweigs, der sich mit der Tradition und Entwicklung des Yoga beschäftigt, bei mir angekommen. Ich habe von dem soge- nannten Hatha-Yoga-Project der School of Oriental and African Studies der University of London erfahren, in der groß aufgestellten Webseite von Modern Yoga Research gestöbert -

Ashtanga Yoga As Taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Copyright ©2000 by Larry Schultz

y Ashtanga Yoga as taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois y Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Do your practice and all is coming (Guruji) To my guru and my inspiration I dedicate this book. Larry Schultz San Francisco, Califórnia, 1999 Ashtanga Ashtanga Yoga as taught by shri k. pattabhi jois Copyright ©2000 By Larry Schultz All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted without the written permission of the author. Published by Nauli Press San Francisco, CA Cover and graphic design: Maurício Wolff graphics by: Maurício Wolff & Karin Heuser Photos by: Ro Reitz, Camila Reitz Asanas: Pedro Kupfer, Karin Heuser, Larry Schultz y I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. His faithful support and teachings helped make this manual possible. forward wenty years ago Ashtanga yoga was very much a fringe the past 5,000 years Ashtanga yoga has existed as an oral tradition, activity. Our small, dedicated group of students in so when beginning students asked for a practice guide we would TEncinitas, California were mostly young, hippie types hand them a piece of paper with stick figures of the first series with little money and few material possessions. We did have one postures. Larry gave Bob Weir such a sheet of paper a couple of precious thing – Ashtanga practice, which we all knew was very years ago, to which Bob responded, “You’ve got to be kidding. I powerful and deeply transformative. Practicing together created a need a manual.” unique and magical bond, a real sense of family. -

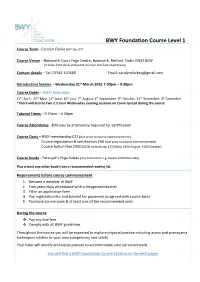

BWY Foundation Course Level 1

BWY Foundation Course Level 1 Course Tutor - Carolyn Clarke BWY Dip: DCT Course Venue – Babworth Court Yoga Centre, Babworth, Retford, Notts DN22 8EW (2 miles from A1 & accessible on main line East coast trains) Contact details – Tel: 07561 107660 Email: [email protected] Introductory Session – Wednesday 31st March 2021 7.00pm – 9.30pm Course Dates – 2021- Saturdays 17th April: 22nd May: 12th June: 10th July: 7th August: 4th September: 9th October: 13th November: 4th December *There will also be two 2.5 hour Wednesday evening sessions on Zoom spread during the course Tutorial Times – 9.45am – 4.30pm Course Attendance - 80% course attendance required for certification Course Costs – BWY membership £37 (due prior to course commencement) Course registration & certification £60 (due prior to course commencement) Course tuition fees £500 (£100 on booking: £150 May: £150 August: £100 October) Course books - Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (any translation e.g. Swami Satchidananda) Plus a least one other book from a recommended reading list Requirements before course commencement 1. Become a member of BWY 2. Two years class attendance with a recognised teacher 3. Fill in an application form 4. Pay registration fee and tutorial fee payments as agreed with course tutor 5. Purchase course book & at least one of the recommended ones During the course v Pay any due fees v Comply with all BWY guidelines Throughout the course you will be expected to explore physical practice including asana and pranayama techniques relative to your own competency and safety. Your tutor will modify and adjust posture to accommodate your personal needs. You will find a BWY Foundation Course Syllabus on the next pages BRITISH WHEEL OF YOGA SYLLABUS - FOUNDATION COURSE 1 The British Wheel of Yoga Foundation Course 1 focuses on basic practical techniques and personal development taught in the context of the philosophy that underpins Yoga. -

Paolo Proietti, Storia Segreta Dello Yoga (Pdf)

Formazione, Promozione e Diffusione dello Yoga 2 “Ma chi si crede di essere lei?” “In India non crediamo di essere, sappiamo di essere.” (Dal film “Hollywood Party”) Ringrazio Alex Coin, Andrea Ferazzoli, Nunzio Lopizzo, Laura Nalin e Andrea Pagano, per il loro prezioso contributo nella ri- cerca storica e nell’editing. 3 Paolo Proietti STORIA SEGRETA DELLO YOGA I Miti dello Yoga Moderno tra Scienza, Devozione e Ideologia 4 5 INDICE PRESENTAZIONE: COSA È LO YOGA ........................................................ 7 LA GINNASTICA COME ARTE DEL CORPO ............................................. 25 SOCRATE, FILOSOFO E GUERRIERO ...................................................... 35 CALANO, IL GYMNOSOPHISTA .............................................................. 43 LO STRANO CASO DEL BUDDHISMO GRECO ........................................ 47 ERRORI DI TRADUZIONE ....................................................................... 55 LA LEGGENDA DELLA LINGUA MADRE ................................................. 61 I QUATTRO YOGA DI VIVEKANANDA .................................................... 71 L’IMPORTANZA DELLO SPORT NELLA CULTURA INDIANA .................. 101 LA COMPETIZIONE COME VIA DI CONOSCENZA ................................. 111 POETI, YOGIN E GUERRIERI ................................................................. 123 KṚṢṆA, “THE WRESTLER” ................................................................... 131 I GRANDI INIZIATI E LA NUOVA RELIGIONE UNIVERSALE. .................. 149 I DODICI APOSTOLI -

Asana Sarvangasana

Sarvângâsana (Shoulder Stand) Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 18, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. Benagh, Barbara. Salamba sarvangasana (shoulderstand). Yoga Journal, Nov 2001, pp. 104-114. Cole, Roger. Keep the neck healthy in shoulderstand. My Yoga Mentor, May 2004, no. 6. Article available online: http://www.yogajournal.com/teacher/1091_1.cfm. Double shoulder stand: Two heads are better than one. Self, mar 1998, p. 110. Ezraty, Maty, with Melanie Lora. Block steady: Building to headstand. Yoga Journal, Jun 2005, pp. 63-70. “A strong upper body equals a stronger Headstand. Use a block and this creative sequence of poses to build strength and stability for your inversions.” (Also discusses shoulder stand.) Freeman, Richard. Threads of Universal Form in Back Bending and Finishing Poses workshop. 6th Annual Yoga Journal Convention, 27-30 Sep 2001, Estes Park, Colorado. “Small, subtle adjustments in form and attitude can make problematic and difficult poses produce their fruits. We will look a little deeper into back bends, shoulderstands, headstands, and related poses. Common difficulties, injuries, and misalignments and their solutions [will be] explored.” Grill, Heinz. The shoulderstand. Yoga & Health, Dec 1999, p. 35. ___________. The learning curve: Maintaining a proper cervical curve by strengthening weak muscles can ease many common pains in the neck. -

Erotic and Physique Studios Photography Collection, Circa 1930-2005 Coll2014-051

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8br8z8d No online items Finding aid to the erotic and physique studios photography collection, circa 1930-2005 Coll2014-051 Michael C. Oliveira ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California © 2017 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 [email protected] URL: http://one.usc.edu Coll2014-051 1 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Erotic and physique studios photography collection creator: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives Identifier/Call Number: Coll2014-051 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet37 boxes. Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2005 Abstract: Photographs produced from the 1930s through 2010 by gay erotic or physique photography studios. The studios named in this collection range from short-lived single person operations to larger corporations. Arrangement This collection is divided into two series: (1) Photographic prints and (2) Negatives and slides. Both series are arranged alphabetically. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Immediate Source of Acquisition This collection comprises photographs garnered from numerous donations to ONE Archives, many of which are unknown or anonymous. Dan Luckenbill, Neil Edwards, Harold Dittmer, and Dan Raymon are among some of the known donors of photographs in this collection.