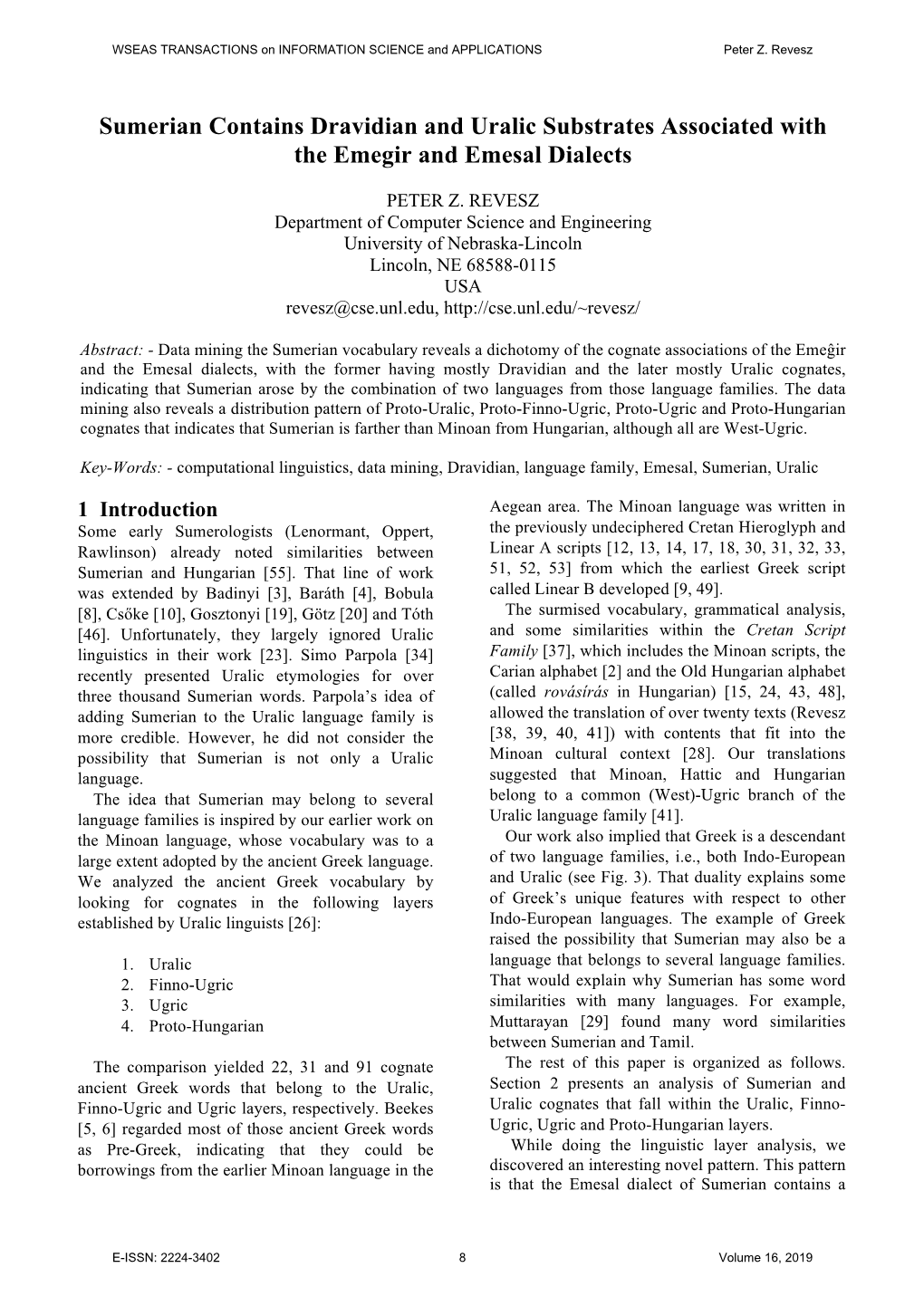

Sumerian Contains Dravidian and Uralic Substrates Associated with the Emegir and Emesal Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Abbreviations of the Names of Languages in the Statistical Maps

V Contents Abbreviations of the names of languages in the statistical maps. xiii Abbreviations in the text. xv Foreword 17 1. Introduction: the objectives 19 2. On the theoretical framework of research 23 2.1 On language typology and areal linguistics 23 2.1.1 On the history of language typology 24 2.1.2 On the modern language typology ' 27 2.2 Methodological principles 33 2.2.1 On statistical methods in linguistics 34 2.2.2 The variables 41 2.2.2.1 On the phonological systems of languages 41 2.2.2.2 Techniques in word-formation 43 2.2.2.3 Lexical categories 44 2.2.2.4 Categories in nominal inflection 45 2.2.2.5 Inflection of verbs 47 2.2.2.5.1 Verbal categories 48 2.2.2.5.2 Non-finite verb forms 50 2.2.2.6 Syntactic and morphosyntactic organization 52 2.2.2.6.1 The order in and between the main syntactic constituents 53 2.2.2.6.2 Agreement 54 2.2.2.6.3 Coordination and subordination 55 2.2.2.6.4 Copula 56 2.2.2.6.5 Relative clauses 56 2.2.2.7 Semantics and pragmatics 57 2.2.2.7.1 Negation 58 2.2.2.7.2 Definiteness 59 2.2.2.7.3 Thematic structure of sentences 59 3. On the typology of languages spoken in Europe and North and 61 Central Asia 3.1 The Indo-European languages 61 3.1.1 Indo-Iranian languages 63 3.1.1.1New Indo-Aryan languages 63 3.1.1.1.1 Romany 63 3.1.2 Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1 South-West Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1.1 Tajiki 65 3.1.2.2 North-West Iranian languages 68 3.1.2.2.1 Kurdish 68 3.1.2.2.2 Northern Talysh 70 3.1.2.3 South-East Iranian languages 72 3.1.2.3.1 Pashto 72 3.1.2.4 North-East Iranian languages 74 3.1.2.4.1 -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

URALIC MIGRATIONS: the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE Václav

URALIC MIGRATIONS: THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE Václav Blažek For the classification of Fenno-Ugric/Uralic languages the following scenarios have been proposed: (1) Mari, Mordvin and Fenno-Saamic as coordinate sub-branches (Setälä 1890) Saamic Fenno- -Saamic Balto-Fennic Fenno- -Volgaic Mordvin Fenno- Mari -Permic Udmurt Fenno-Ugric Permic Komi Hungarian Ugric Mansi. Xanty (2) Mordvin and Mari in a Volgaic group (Collinder 1960, 11; Hajdú 1985, 173; OFUJ 1974, 39) Saamic North, East, South Saami Baltic Finnic Finnish, Ingrian, Karelian, Olonets, Ludic, Fenno-Volgaic end of the 1st mill. BC Vepsian, Votic, Estonian, Livonian 1st mill BC Mordvin Fenno- -Permic Volgaic Mari mid 2nd mill. BC Udmurt Finno-Ugric Permic end of the 8th cent. AD Komi 3rd mill. BC Hungarian Uralic Ugric 4th mill. BC mid 2st mill. BC Mansi, Xanty North Nenets, Enets, Nganasan Samoyedic end of the 1st mill. BC South Selkup; Kamasin (3) A model of a series of sequential separations by Viitso (1996, 261-66): Mordvin and Mari represent different separations from the mainstream, formed by Ugric. Fenno-Saamic Finno- Mordvin -Ugric Mari Uralic Permic Ugric (‘Core’) Samoyedic (4) The first application of a so-called ‘recalibrated’ glottochronology to Uralic languages was realized by the team of S. Starostin in 2004. -3500 -3000 -2500 -2000 -1500 -1000 -500 0 +500 +1000 +1500 +2000 Selkup Mator Samojedic -720 -210 Kamasin -550 Nganasan -340 Enets +130 Nenets Uralic Khanty -3430 Ugric Ob- +130 Mansi -1340 -Ugric Hungarian Komi Fenno-Ugric Permic +570 Udmurt -2180 Volgaic -1370 Mari -1880 Mordva -1730 Balto-Fennic Veps +220 Estonian +670 Finnish -1300 Saamic Note: G. -

B. the Program in Uralic and Altaic Studies Originated During the Academic Year

B. The Program in Uralic and Altaic Studies originated during the academic year 1960-1961, when it was known as a Comittee on Uralic and Altaic Studies. In the academic year 1961-1962 ta Jt it was transformed into a Program which then dealt, mainly with Uralic Studies - Finnish and Hungarian language and area studies. As it expanded a more complete range of courses in Uralic and Altaic Language and Area Studies were offered, and to-day the Program is probably the most comprehensive of its kind in the United States, and enjoys a world-wide reputation. Uralic and Altaic Studies is a relatively unconventional field of study concerned with an area that plays an increasing role in world affairs and embarces a great part of the Eurasian Continent. It compriaes a field of study which has hitherto been neglected in the United States. This Program now provides the much needed research facilities for graduate and doctoral students which enables them to become specialized in this field, and meets the growing need for specialists and academicians in this area. The Program offers a degree of Mafter of Arts with specialization in either Uralic or Altaic Studies. An Independent doctoral Program in Uralic and Altaic will be established during the course of the coming year. In the meantime, candidates for the Ph.D. degree present their specialization in Uralic or Altaic Studies to the curricular unit appropriate to the student' a major interest, such as linguistics, history, Asian Studies, folklore, etc. Apart from these above mentioned degrees, the Program also offers a Certificate in Hungarian Studies which is designed to stimulate interest and specialization among students who would already have accumulated some of the requirements towards unkhux another degree. -

Central Anatolian Languages and Language Communities in the Colony Period : a Luwian-Hattian Symbiosis and the Independent Hittites*

1333-08_Dercksen_07crc 05-06-2008 14:52 Pagina 137 CENTRAL ANATOLIAN LANGUAGES AND LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES IN THE COLONY PERIOD : A LUWIAN-HATTIAN SYMBIOSIS AND THE INDEPENDENT HITTITES* Petra M. Goedegebuure (Chicago) 1. Introduction and preliminary remarks This paper is the result of the seemingly innocent question “Would you like to say something on the languages and peoples of Anatolia during the Old Assyrian Period”. Seemingly innocent, because to gain some insight on the early second millennium Central Anatolian population groups and their languages, we ideally would need to discuss the relationship of language with the complex notion of ethnicity.1 Ethnicity is a subjective construction which can only be detected with certainty if the ethnic group has left information behind on their sense of group identity, or if there is some kind of ascription by others. With only the Assyrian merchant documents at hand with their near complete lack of references to the indigenous peoples or ethnic groups and languages of Anatolia, the question of whom the Assyrians encountered is difficult to answer. The correlation between language and ethnicity, though important, is not necessarily a strong one: different ethnic groups may share the same language, or a single ethnic group may be multilingual. Even if we have information on the languages spoken in a certain area, we clearly run into serious difficulties if we try to reconstruct ethnicity solely based on language, the more so in proto-historical times such as the early second millennium BCE in Anatolia. To avoid these difficulties I will only refer to population groups as language communities, without any initial claims about the ethnicity of these communities. -

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language Emilie´ Page-Perron´ †, Maria Sukhareva‡, Ilya Khait¶, Christian Chiarcos‡, † University of Toronto [email protected] ‡ University of Frankfurt [email protected] [email protected] ¶ University of Leipzig [email protected] Abstract cuses on the application of NLP methods to Sume- rian, a Mesopotamian language spoken in the This paper presents a newly funded in- 3rd millennium B.C. Assyriology, the study of ternational project for machine transla- ancient Mesopotamia, has benefited from early tion and automated analysis of ancient developments in NLP in the form of projects cuneiform1 languages where NLP special- which digitally compile large amounts of tran- ists and Assyriologists collaborate to cre- scriptions and metadata, using basic rule- and ate an information retrieval system for dictionary-based methodologies.4 However, the Sumerian.2 orthographic, morphological and syntactic com- This research is conceived in response to plexities of the Mesopotamian cuneiform lan- the need to translate large numbers of ad- guages have hindered further development of au- ministrative texts that are only available in tomated treatment of the texts. Additionally, dig- transcription, in order to make them acces- ital projects do not necessarily use the same stan- sible to a wider audience. The method- dards and encoding schemes across the board, and ology includes creation of a specialized this, coupled with closed or partial access to some NLP pipeline and also the use of linguis- projects’ data, limits larger scale investigation of tic linked open data to increase access to machine-assisted text processing. -

The Finnish Korean Connection: an Initial Analysis

The Finnish Korean Connection: An Initial Analysis J ulian Hadland It has traditionally been accepted in circles of comparative linguistics that Finnish is related to Hungarian, and that Korean is related to Mongolian, Tungus, Turkish and other Turkic languages. N.A. Baskakov, in his research into Altaic languages categorised Finnish as belonging to the Uralic family of languages, and Korean as a member of the Altaic family. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Finnish is closer to Korean than to Hungarian, and that likewise Korean is closer to Finnish than to Turkic languages . In his analytic work, "The Altaic Family of Languages", there is strong evidence to suggest that Mongolian, Turkic and Manchurian are closely related, yet in his illustrative examples he is only able to cite SIX cases where Korean bears any resemblance to these languages, and several of these examples are not well-supported. It was only in 1927 that Korean was incorporated into the Altaic family of languages (E.D. Polivanov) . Moreover, as Baskakov points out, "the Japanese-Korean branch appeared, according to (linguistic) scien tists, as a result of mixing altaic dialects with the neighbouring non-altaic languages". For this reason many researchers exclude Korean and Japanese from the Altaic family. However, the question is, what linguistic group did those "non-altaic" languages belong to? If one is familiar with the migrations of tribes, and even nations in the first five centuries AD, one will know that the Finnish (and Ugric) tribes entered the areas of Eastern Europe across the Siberian plane and the Volga. -

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars Number 2

oi.uchicago.edu i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS NUMBER 2 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii MARGINS OF WRITING, ORIGINS OF CULTURES edited by SETH L. SANDERS with contributions by Seth L. Sanders, John Kelly, Gonzalo Rubio, Jacco Dieleman, Jerrold Cooper, Christopher Woods, Annick Payne, William Schniedewind, Michael Silverstein, Piotr Michalowski, Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Theo van den Hout, Paul Zimansky, Sheldon Pollock, and Peter Machinist THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS • NUMBER 2 CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2005938897 ISBN: 1-885923-39-2 ©2006 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago Co-managing Editors Thomas A. Holland and Thomas G. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Katie L. Johnson is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Front Cover Illustration A teacher holding class in a village on the Island of Argo, Sudan. January 1907. Photograph by James Henry Breasted. Oriental Institute photograph P B924 Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Infor- mation Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. -

"Evolution of Human Languages": Current State of Affairs

«Evolution of Human Languages»: current state of affairs (03.2014) Contents: I. Currently active members of the project . 2 II. Linguistic experts associated with the project . 4 III. General description of EHL's goals and major lines of research . 6 IV. Up-to-date results / achievements of EHL research . 9 V. A concise list of actual problems and tasks for future resolution. 18 VI. EHL resources and links . 20 2 I. Currently active members of the project. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Center for Comparative Studies, Russian State University for the Humanities (Moscow). Web info: http://ivka.rsuh.ru/article.html?id=80197 George Publications: http://rggu.academia.edu/GeorgeStarostin Starostin Research interests: Methodology of historical linguistics; long- vs. short-range linguistic comparison; history and classification of African languages; history of the Chinese language; comparative and historical linguistics of various language families (Indo-European, Altaic, Yeniseian, Dravidian, etc.). Primary affiliation: Visiting researcher, Santa Fe Institute. Formerly, professor of linguistics at the University of Melbourne. Ilia Publications: http://orlabs.oclc.org/identities/lccn-n97-4759 Research interests: Genetic and areal language relationships in Southeast Asia; Peiros history and classification of Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, Austroasiatic languages; macro- and micro-families of the Americas; methodology of historical linguistics. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow / Novosibirsk). Web info / publications list (in Russian): Sergei http://www.inslav.ru/index.php?option- Nikolayev =com_content&view=article&id=358:2010-06-09-18-14-01 Research interests: Comparative Indo-European and Slavic studies; internal and external genetic relations of North Caucasian languages; internal and external genetic relations of North American languages (Na-Dene; Algic; Mosan). -

On the Similarities and Differences Between the Mongolic, Tungusic, and Eskimo-Aleut Languages

ON THE SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE MONGOLIC, TUNGUSIC, AND ESKIMO-ALEUT LANGUAGES Shinjiro Kazama Tokyo University of Foreign Studies This paper is an attempt at a contrastive typological analysis of selected struc- tural features of three language families: Mongolic, Tungusic, and Eskimo- Aleut (EskAleutic). While Mongolic and Tungusic, together with Japanese (Japonic) and Korean (Koreanic), are known to share many structural features in the context of the so-called Altaic phenomenon, many of these features are not particularly diagnostic and might even be regarded as coincidental with perhaps the single exception of obviative person marking. This is a feature attested also in Eskimo-Aleut. The present paper offers a somewhat more detailed discussion of this, as well as of other typological similarities and differ- ences between the three language families in the areal context of the North Pacific region. Данная статья является попыткой сопоставительного типологического анализа некоторых особенностей монгольских, тунгусских и эскимосско-алеутских языков. Как известно, монгольские и тунгусские языки, а также японский и корейский языки, имеют немало общих черт в контексте так называемого алтайского феномена, но многие из них не имеют особенно большого диагностического значения и могут быть даже случайными. Исключением является обвиативное лицо, которое встречается и в эскимосско-алеутских языках. Эта черта, а также некоторые другие типлогические совпадения и расхождения между названными группами языков рассматриваются в статье в контексте Северо-Тихоокеанского региона. 1. INTRODUCTION In Kazama (2003) I attempted to contrast typologically three so-called Altaic language groups (Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic), together with the Korean and Japanese languages. I endeavoured to contrast these languages in detail, dealing with as many features as possiblе. -

Survey of the World's Languages

Survey of the world’s languages The languages of the world can be divided into a number of families of related languages, possibly grouped into larger stocks, plus a residue of isolates, languages that appear not to be genetically related to any other known languages, languages that form one-member families on their own. The number of families, stocks, and isolates is hotly disputed. The disagreements centre around differences of opinion as to what constitutes a family or stock, as well as the acceptable criteria and methods for establishing them. Linguists are sometimes divided into lumpers and splitters according to whether they lump many languages together into large stocks, or divide them into numerous smaller family groups. Merritt Ruhlen is an extreme lumper: in his classification of the world’s languages (1991) he identifies just nineteen language families or stocks, and five isolates. More towards the splitting end is Ethnologue, the 18th edition of which identifies some 141 top-level genetic groupings. In addition, it distinguishes 1 constructed language, 88 creoles, 137 or 138 deaf sign languages (the figures differ in different places, and this category actually includes alternate sign languages — see also website for Chapter 12), 75 language isolates, 21 mixed languages, 13 pidgins, and 51 unclassified languages. Even so, in terms of what has actually been established by application of the comparative method, the Ethnologue system is wildly lumping! Some families, for instance Austronesian and Indo-European, are well established, and few serious doubts exist as to their genetic unity. Others are quite contentious. Both Ruhlen (1991) and Ethnologue identify an Australian family, although there is as yet no firm evidence that the languages of the continent are all genetically related. -

NUMERALS 1 0.1. GENERAL the Sumerian Language Had A

CHAPTER TEN NUMERALS 10.1. GENERAL The Sumerian language had a "sexagesimal" system in which numer ation proceeded in alternating steps of 10 and 6: 1-10, 10-60, 60- 600, 600-3600, 3600-36000, 36000-216000. With sixty as the "hun dred", Sumerian numeration had the enormous advantage of being able to divide by 3 or 6 without leaving a remainder. The sexa gesimal system has left its traces in our modern divisions of the hour or of the compass. It permeates the metrological systems of the Ancient Near East. Powell 1971; 1989. Since cardinal and ordinal numbers, including fractions, as well as notations of length, surface, volume, capacity, and weight are next to exclusively written with number signs, we are poorly informed on the pronunciation and the morpho-syntactical behaviour of numbers in Sumerian. To what degree were numbers subject to case inflection? If 600 was pronounced ges-u "sixty ten", i.e., "ten (times) sixty", what was the pronunciation of "sixty (plus) ten", i.e., 70? Was there a difference of stress or some other means of intonation, e.g., *[ges(d)u] versus [gd(d)u]? Syntactically, persons or things counted were followed, not pre ceded, by numerals so that the position of a numeral corresponds to that of an adjective. For-purely graphic-exceptions to this rule see 5.3.6, note. 10.2. CARDINAL NUMBERS The oldest pronunciation guide for the Sumerian cardinal numbers 2 to 10 is an exercise tablet from Ebla: TM 75.G. 2198: Edzard 1980; 2003b. 62 CHAPTER TEN Ebla later tradition 1.