Two Field Experiments Investigating the Effect of Celebrity Endorsement on Charitable Fundraising Campaigns1 Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17

Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2017 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport BBC Pay Disclosures July 2017 Report from the BBC Remuneration Committee of people paid more than £150,000 of licence fee revenue in the financial year 2016/17 1 Senior Executives Since 2009, we have disclosed salaries, expenses, gifts and hospitality for all senior managers in the BBC, who have a full time equivalent salary of £150,000 or more or who sit on a major divisional board. Under the terms of our new Charter, we are now required to publish an annual report for each financial year from the Remuneration Committee with the names of all senior executives of the BBC paid more than £150,000 from licence fee revenue in a financial year. These are set out in this document in bands of £50,000. -

20 February 2015

20 FEBRUARY 2015 30 years to the day EastEnders was first broadcast, one of EastEnders true icons, Kathy Beale returned to the show in a LIVE scene in last night’s episode in the UK, which will air in Australia on the 4th March on UKTV at 6.15pm. Last seen in 2000 before returning to South Africa, viewers believed that Kathy was killed in a car crash. However when Kathy comes home to Walford later this year, viewers will learn where Kathy has been and why she has stayed away so long… Played by Gillian Taylforth, Kathy appeared in the very first episode of EastEnders on the 19th February 1985. As one of the original cast, Gillian soon found herself at the heart of some of the soaps most memorable episodes, creating a character that has never been forgotten in EastEnders history. Storylines included her relationship and subsequent turbulent marriage to Phil Mitchell and the rape of Kathy by Wilmott Brown. Kathy’s return has been shrouded in secrecy. To keep her return under wraps the scenes were shot live on location to prevent her being seen prior to her episode transmitting. Talking about her return to EastEnders, Gillian said “When Dominic approached me with his plan, I was so shocked I got into my car and burst into tears! ‘Kathy’ has always been so close to my heart and it’s absolutely wonderful to be returning to the show and reprising the role” Dominic Treadwell-Collins, Executive Producer said “I have always made my feelings on Kathy Beale and Gillian Taylforth very clear – she is part of EastEnders history, mother to Ian and Ben and one of the most important and iconic television characters on British television. -

Thesis Final Draft.Pages

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Glasgow Theses Service Bell, Stuart (2016) "Don't Stop": Re-Thinking the Function of Endings in Narrative Television. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7282/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] “Don’t Stop…” Re-thinking the Function of Endings in Narrative Television Stuart Bell (MA, MLitt) Submitted in fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow November 2015 (c) Stuart Bell, November 2015 !1 Abstract “Don’t Stop…” Re-thinking the Function of Endings in Television This thesis argues that the study of narrative television has been limited by an adherence to accepted and commonplace conceptions of endings as derived from literary theory, particularly a preoccupation with the terminus of the text as the ultimate site of cohesion, structure, and meaning. Such common conceptions of endings, this thesis argues, are largely incompatible with the realities of television’s production and reception, and as a result the study of endings in television needs to be re-thought to pay attention to the specificities of the medium. -

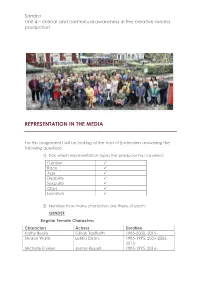

Representation in the Media

Sandra Unit 4 – critical and contextual awareness in the creative media production REPRESENTATION IN THE MEDIA For this assignment I will be looking at the cast of Eastenders answering the following questions: 1) Tick which representation types the producer has covered: Gender Race Age Disability Sexuality Class Location 2) Number how many characters are there of each: GENDER Regular Female Characters Characters Actress Duration Kathy Beale Gillian Taylforth 1985-2000, 2015- Sharon Watts Letitia Dean 1985-1995, 2001-2006, 2012- Michelle Fowler Jenna Russell 1985-1995, 2016- Susan Tully Dot Cotton June Brown 1985-1993, 1997- Sonia Fowler Natalie Cassidy 1993-2007, 2010-2011, 2014- Rebecca Fowler Jasmine Armfield 2000, 2002, 2005-2007, Jade Sharif 2014- Alex and Vicky Gonzalez Louise Mitchell Tilly Keeper 2001-2003, 2008, 2010, Brittany Papple 2016- Danni Bennatar Rachel Cox Jane Beale Laurie Brett 2004-2012, 2014- Stacey Slater Lacey Turner 2004-2012, 2014- Jean Slater Gillian Wright 2004- Honey Mitchell Emma Barton 2005-2008, 2014- Denise Fox Diana Parish 2006- Libby Fox Belinda Owusu 2006-2010, 2014- Abi Branning Lorna Fitzgerald 2006- Lauren Branning Jacqueline Jossa 2006- Madeline Duggan Shirley Carter Linda Henry 2006- Whitney Dean Shona McGarty 2008- Kim Fox Tameka Empson 2009- Glenda Mitchell Glynis Barber 2010-2011, 2016- Tina Carter Luisa Bradshaw-White 2013- Linda Carter Kellie Bright 2013- Donna Yates Lisa Hammond 2014- Carmel Kazemi Bonnie Langford 2015- Madison Drake Seraphina Beh 2017- Alexandra D‘Costa Sydney Craven -

EXETER COLLEGE Register 2016 Contents

REGISTER 2016 REGISTER EXETER COLLEGE EXETER COLLEGE EXETER COLLEGE Register 2016 Contents Editorial 2 From the Rector 2 From the President of the MCR 5 From the President of the JCR 7 From the Chaplain 9 From the Director of Development 12 The Building of the College Hall 13 Departing Fellows 19 Incoming Fellows 24 Student Research: The First National Purity Congress 28 The Rector’s Seminars 30 Student Societies and Associations 32 Building Exeter’s Second Quadrangle: The Evolution of the Back Quad 37 The Governing Body 47 Honorary Fellows 49 Emeritus Fellows 50 Honours and Appointments 51 Obituaries 52 Publications Reported 59 The College Staff 61 Class Lists in Honour Schools 66 Distinctions in Prelims and First Class Moderations 67 Graduate Degrees 68 Major Scholarships, Studentships, and Bursaries 71 College, University, and Other Prizes 73 Freshers 2015 76 Births, Civil Partnerships, Marriages, and Deaths 83 Notices 86 Contributors 88 1 Editorial The College continues to prepare for the opening of Cohen Quadrangle, and this year’s Register explores two historic building schemes: the Hall of 1618/19 and the extension of the Margary (Back) Quad in the 1930s-1960s. The new form of the Register seems to have been well received and, as readers will see, is followed again this year. I would like to thank the contributors, and Sam Williamson (2011 Lit. Hum.) for his help in proof reading. Andrew Allen From the Rector Deaths reported during 2015/16 included that of Bennett Boskey (Honorary Fellow), a distinguished Washington lawyer who was a major benefactor to the Williams Programme at Exeter. -

Dreary Downton's Dying in Hospital

DM1ST TUESDAY 13.10.2015 DAILY MIRROR 23 TV SIOBHAN McNALLY Guest TV columnist Tarrant’s on Neil’s archaeo-log-y Luscious-locked Celtic salt mine in plight track Neil Oliver goes Austria. “It still digging to find the smells when it Channel 5’s new real story of the gets wet,” sniggers offering is Chris Dreary Downton’s Celts in BBC2’s the guide, and we Tarrant: Extreme three-part series, watch as two high- Railways. But the The Celts: Blood, minded prominent only extreme Iron and Sacrifice. archaeologists thing about this But despite an behave like a pair new Channel 5 amazing haul of bronze of schoolboys over an Iron series, is the artefacts which prove the Age poo. extreme length TV marauding Celts also liked “Go on, I dare you touch executives were clearly willing to dying in hospital their bling, Neil – who’s to it with your tongue,” is go to get the former Who Wants WITH plotlines like “Shall we garters? Now that the Earl’s randy more Age of Aquarius what I bet any money that To Be A Millionaire presenter as than Iron Age – is far more Neil said to the Austrian far away as possible from them. go for a walk?” and “I’ll be in daughter has given up trying to disguise the fact that she’s interested in the ancient when the cameras were Other than that, the main thing the drawing room”, it’s no faecal remains left in a switched off. we learn from this show is that surprise the sixth and final a complete slapper, she’s free under-investment in railways is a series of ITV’s Downton Abbey to pursue the dashing racing global problem. -

Jerome Lynch QC

Jerome Lynch QC Year of Silk/Call: 2000/1983 Call Clerk on 020 7827 4000 PRACTICE AREAS OVERVIEW He is currently seconded to Trott & Duncan in Bermuda undertaking a number of important "political" trials in Bermuda, appearing inter alia for the former premier Dr Ewart Brown in the recent Commission of Inquiry and in the Turks and Caicos Islands, the Hon McAllister (Piper) Hanchell, former minister for Natural Resources, on charges of corruption, bribery and money laundering. His practice is predominantly defending in serious crime, dealing with charges of tax evasion and SFO prosecutions. He specialises in white-collar offences, fraud, corruption, Companies Act breaches, murder "gangland and honour killings" and "terrorist" offences. He undertakes work throughout the Caribbean called to the Bar in Bermuda, TCI, BVI and Cayman. He is registered to receive work by direct access. His pro bono work has ranged far and wide included death row cases and fighting major Public Inquiries. He is the son of a Swiss mother and Jamaican father. He started his working life as a salesman selling everything from light bulbs and encyclopaedias to advertising space and insurance. He gave that up and chose to study law. He has practised as a lawyer ever since. His current interests include climbing (weakly), hiking (slowly), skiing (speedily), golf (badly) and wine (copiously). APPOINTMENTS AND MEMBERSHIPS Criminal Bar Association, International Bar Association. PUBLICATIONS AND TRAINING He has trained in advocacy, ethics and case presentation for Lincoln's Inn and has taught lawyers in UK, Jamaica, TCI, Mauritius and Bermuda in both civil and criminal matters. -

Melanie Blake Author and Celebrity Agent Media Masters – September 19, 2019 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Melanie Blake Author and Celebrity Agent Media Masters – September 19, 2019 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one-to-one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today I’m joined by Melanie Blake, entrepreneur and chief executive of Urban Associates. Melanie started her music career at Top of the Pops, working with acts like Destiny’s Child, All Saints and the Spice Girls. And as one of the UK’s leading music and entertainment managers, she has a roster of award-winning artists who have sold more than 100 million records. Ten years later, Melanie downsized her business to focus on writing – first as a columnist for the Sunday People and the Daily Mirror, then as a playwright, and now as a novelist. Her first book, The Thunder Girls, is a story of glamour and revenge set in the world of pop girl bands, and has already inspired a play. Mel, thank you for joining me. Thanks for having me. Well, let’s start with the success of your first novel, The Thunder Girls. It says, “A story of glamour and revenge set in the world of pop girl bands.” Well, I’ve certainly done what they say, which is they say write about what you know. And the funny thing about The Thunder Girls is that although it’s a best seller, it’s probably the longest running job to get a best seller ever, because it took 20 years to get it out. Wow. -

How the Law Works, Second Edition

How the Law Works SECOND EDITION Gary Slapper “How the Law Works is a very useful companion to anyone embarking on the study of law.” Andrew Baker, Liverpool John Moores University “How the Law Works is a comprehensive, witty and easy-to-read guide to the law. I thoroughly recommend it to non-lawyers who want to improve their knowledge of the legal system and to potential students as an introduction to the law of England and Wales.”Lynn Tayton QC Reviews of the fi rst edition: “A friendly, readable and surprisingly entertaining overview of what can be a daunting and arcane subject to the outsider.” The Law Teacher “An easy-to-read, fascinating book ... brimful with curios, anecdote and explanation.” The Times How the Law Works is a refreshingly clear and reliable guide to today’s legal system. Offering interesting and comprehensive coverage, it makes sense of all the curious features of the law in day to day life and in current affairs. Explaining the law and legal jargon in plain English, it provides an accessible entry point to the different types of law and legal techniques, as well as today’s compensation culture and human rights law. In addition to explaining the role of judges, lawyers, juries and parliament, it clarifies the mechanisms behind criminal and civil law. How the Law Works is essential reading for anyone approaching law for the first time, or for anyone who is interested in an engaging introduction to the subject’s bigger picture. How the Law Works SECOND EDITION GARY SLAPPER LLB, LLM, PhD, PGCE (Law) Professor of Law, and Director of the Law School at The Open University Visiting Professor, New York University, London Second edition published 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010. -

Mailonline - News, Sport, Celebrity, Science and Health Stories U.K

MailOnline - news, sport, celebrity, science and health stories U.K. India U.S. News Sport TV&Showbiz Femail Health Science Money Video Coffee Break Travel Columnists TV&Showbiz Home U.S. Showbiz Headlines Arts A-Z Star Search Pictures Showbiz Boards Login Monday, Feb 2nd 2015 11AM 26°C 2PM 29°C 5-Day Forecast Working off the Christmas pounds? Yo-yo dieter Lauren Goodger displays a much FU LLER figure as she works out on the beach in tiny orange bikini By Mail Online Reporter Published: 00:08 GMT, 2 February 2015 | Updated: 00:53 GMT, 2 February 2015 40 shares 130 View comments She has previously insisted that she feels sexy at any size and Lauren Goodger c ertainly wasn't letting a few extra pounds stop her having fun on the beach in E gypt recently. The 28-year-old former TOWIE star flaunted her extremely curvaceous figure as sh e strutted along the beach in a teeny-tiny orange bikini, the same colour as her fake-tanned body, which could barely contain her assets. Lauren, whose battles with her weight have been well documented, revealed a much fuller figure, a far cry from the toned body she has flaunted in the past. Scroll down for video Fuller figure: Lauren Goodger showed off a decidedly more curvaceous figure as s he hit the beach in Egypt recently +14 Fuller figure: Lauren Goodger showed off a decidedly more curvaceous figure as s he hit the beach in Egypt recently However, Lauren never lets a few extra pounds stop her from feeling 'sexy', prev iously explaining to Closer magazine: 'No matter what my weight, I always feel s exy.' Opening up about her sex life, Lauren: 'You've got to let yourself go. -

V12-Full.Pdf

A Barker’s Dozen Life Among The Dog People of Paddington Rec. Volume XII Anthony Linick Introduction The same day that we returned after two months in California – having decided that we would not be moving back to the States at the beginning of our retirement – my wife Dorothy and I took our property off the market … and ordered a puppy. Fritz the Schnauzer arrived a few weeks later and by the end of June, 2003, we had entered that unique society of dog owners who people London’s Paddington Recreation Ground. The society in which we were now to take our place remains a unique one, an ever-changing kaleidoscope of dogs and their owners. The dogs represent most of the popular breeds and many of the mutt-like mixtures – and so do their accompanying humans, who come from diverse nationalities and from many walks of life: professionals and job seekers, young and old, family members and loners. They are united by their love of dogs, and on the central green of the park, on its walkways and at the café where they gather after exercising their animals, they often let this affection for dogs carry them into friendships that transcend park life and involve many of them in additional social activities. Fritz had been a member of the pack for about a year when I decided to keep a daily record of his antics and the folkways of the rest of the crew, human and canine. I have done so ever since. I reasoned that not only would this furnish us with an insight into the relationship of man and beast but that it would also provide a glimpse into London life. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\Desktop

1 THE QUEER CARNIVAL: Gender transgressive images in contemporary Queer performance and their relationship to carnival and the Grotesque. Submitted by Bruce Howard Bayley to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama, (February 2000). This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all the material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred upon me. ___________________________ Bruce Howard Bayley 2 ABSTRACT The starting point for this study was my MA research into dramatherapy interventions with young male clients whose self-images contained indicators of both male and female genders alongside one another and who identified with a kind of gender fluidity which put them outside the duality of the male-female gender system. This study is an exploration of contemporary Queer performers whose work can be seen as embodying positions similar to those taken by my dramatherapy clients. PART ONE contains a description of the performances I observed and extracts from interviews conducted. PART TWO consists of my analysis of the performances. After a discussion of the theories of gender identity that underpin my research, there follows a presentation of the terms ‘gender transgression’ and ‘gender fluidity’ and a consideration of the extent to which the gender transgressive images embodied in the work of these performers can be considered to be liminal and/or liminoid phenomena.