A Note on “The 1001 Seances”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGL 261 Advanced Literary Theory

ENGL 261: ADVANCED LITERARY THEORY: QUEER AND POST-QUEER THEORIES OF GENDER, SEXUALITY, AND ABILITY ADAM JOHN WATERMAN FALL 2016 9:30 – 10:45 TR FISK HALL 313 COURSE DESCRIPTION Institutionalized in the 1990s, early queer theory challenged many of the conventions of identitarian-based social formation and political organizing that had characterized gay and lesbian sociality, in the United States, since the 1940s. Drawing on post-structuralist theory, queer theorists sought to explore the processes by which medicalized categories of sexual deviance—where sexual deviance was measured in relation to a wide range of non-reproductive sexual practices—became taken as embodied forms of social and cultural identity. Over time, the scope of queer theory has expanded, such that it now represents a broad range of methodologies by which a host of norms are interrogated and named. Post-queer theory, as such, has left behind its moorings in lesbian and gay studies, to become a mechanism of critique where by theorists explore the sociality of sex, and the sexuality of the social. This course will expose students to a range of works in queer and post-queer theory as part of a larger exploration of methodologies in literary and cultural studies. As fields of scholarship routed through concepts of intersectionality and assemblage, queer and post-queer theories explore the imbrication of race, gender, and sexuality, as well as political economy, the question of disability, and class. REQUIRED TEXTS Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, -

Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing

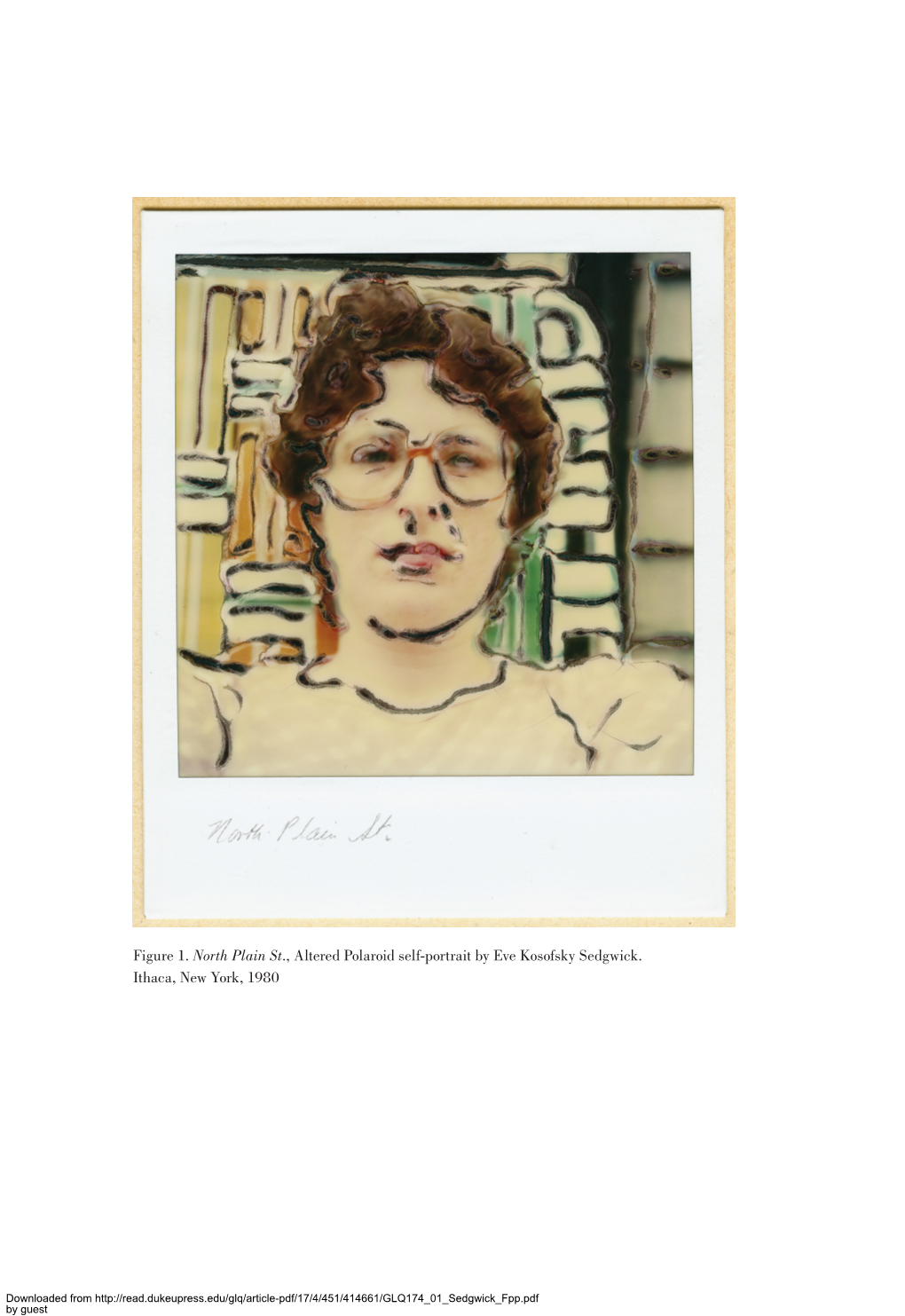

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing Allen Durgin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/482 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEPRESSIVES & THE SCENES OF QUEER WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 ALLEN DURGIN All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Robert Reid-Pharr, Chair of Committee Date Mario DiGangi, Executive Officer Wayne Koestenbaum Steven F. Kruger THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT DEPRESSIVES AND THE QUEER SCENES OF WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN Adviser: Professor Robert Reid-Pharr My dissertation attempts to answer the question: What exactly does a reparative reading look like? The question refers to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s provocative essay on paranoid and reparative reading practices, in which Sedgwick describes how the hermeneutics of suspicion has become central to a whole range of intellectual projects across the humanities and social sciences. Criticizing this dominant critical mode for its political blindness and unintended replication of repressive social structures, Sedgwick looks for an alternative in what she calls reparative reading. -

Theory Matters

Edited by Martin Middeke and Christoph Reinfandt Theory Matters The Place of Theory in Literary and Cultural Studies Today Theory Matters Martin Middeke • Christoph Reinfandt Editors Theory Matters The Place of Theory in Literary and Cultural Studies Today Editors Martin Middeke Christoph Reinfandt Chair of English Literature Chair of English Literature University of Augsburg University of Tübingen Augsburg , Germany Tübingen , Germany ISBN 978-1-137-47427-8 ISBN 978-1-137-47428-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-47428-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016942080 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

A Few Lies: Queer Theory and Our Method Melodramas David Kurnick

A Few Lies: Queer Theory and Our Method Melodramas David Kurnick ELH, Volume 87, Number 2, Summer 2020, pp. 349-374 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/elh.2020.0011 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/757342 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] A FEW LIES: QUEER THEORY AND OUR METHOD MELODRAMAS BY DAVID KURNICK “We have been telling a few lies”: the words mark the end of what we could call the overture of Leo Bersani’s 1987 essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?”1 The lies Bersani is referring to are, in the first place, the dignifying fantasies gay male activists have spun about the necessarily liberatory consequences of same-sex attraction. Right-wing politics, he has just reminded us, consort quite nicely with some men’s “marked sexual preference for sailors and telephone linemen.”2 He is about to tear off into what for some of us, more than thirty years later, remains a famous rebuttal of Dennis Altman’s claims for the gay bathhouse as a space of Whitmanian democracy. Bersani begs to differ: “Your looks, muscles, hair distribution, size of cock, and shape of ass determined exactly how happy you were going to be during those few hours[.]”3 Such deflationary rhetoric is, of course, one of Bersani’s hallmarks. But he’s not alone in it. In fact, uncomfortable truth-telling constitutes a central tradition in what we have for a while been calling queer culture. -

Eve Kosofiky Sedgwick

TENDENCIES EDITED BY MICHELE AINA BARALE, JONATHAN GOLDBERG, MICHAEL MOON, AND EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK Eve Kosofiky Sedgwick DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham 1993 Second printing, 1994 © 1993 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper @ Typeset in Sabon by Tseng Information Systems Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. "Queer and Now" first appeared in Mark Edmund son, ed., Wild Orchids and Trotsky: Messages from American Universities (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), pp. 237-66, © 1993 by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. "Privilege of Unknowing" previously appeared in Gen ders 1 (Spring 1988): 102-24, and is reprinted by permission. "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" first appeared in Critical Inquiry 17.4 (Summer 1991): 818-37, © 1991 by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. t "Epidemics of the Will" previously appeared in Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter, ecls., Incorporations (New York: Zone, 1992), pp. 582-95, and is reprinted by permission. "Nationalisms and Sexualities" previously appeared in Andrew Parker, Mary Russo, Doris Sommer, and Patricia Yaeger, eds., Nationalisms and Sexualities (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 235-45, and is re printed by permission. "How to Bring Your Kids Up Gay" first appeared in Social Text 29 (1991): 18-27, © 1991 by Social Text, and is reprinted by permission. "Willa Cather and Others" first appeared as "Across Gender, Across Sexuality: Willa Cather and Others," in South Atlantic Quarterly 88.1 (Winter 1989): 53 72, © 1989 by Duke University Press. "A Poem Is Being Written" previously appeared in Representations 17 (Winter 1987): 110-43, © 1987 by the Regents of the University of California, and is re printed by permission. -

Book Review: Epistemology of the Closet

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 9 Issue 3 Article 13 December 1991 Book Review: Epistemology of the Closet Mark Reschke Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Mark Reschke, Book Review: Epistemology of the Closet, 9(3) LAW & INEQ. 567 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol9/iss3/13 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. BOOK REVIEW Epistemology of the Closet by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick* Reviewed by Mark Reschke** In the 1980s, homophobic attacks from many fronts became almost commonplace. In that same decade, the gay and lesbian rights movement redoubled its efforts and academic explorations of "minority" sexualities burgeoned. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet appears in the early 1990s like a "miss- ing link" in the evolution of gay and lesbian studies and politics.' Sedgwick's contribution hovers in the filmy intellectual plane of theory, but it is the kind of theory that transforms, providing shape to the past and possibilities for the future. The transformative power behind Sedgwick's theory manifests itself in four important ways: it calls attention to a crisis at the foundation of current lesbian and gay political strategies; it directs the discourse of gay studies through and beyond the essen- tialist-social constructionist debate which has dominated the field in recent years; it establishes that the homosexual-heterosexual definitional divide is a central controlling factor in all modem Western identities and social organizations, not merely in homo- sexual identities and organizations; and it opens a space for those nongays who have sufficient knowledge and awareness of their own privilege and homophobia to investigate gay and lesbian is- sues, or, to put it in Sedgwick's terms, to engage in "an- tihomophobic" projects. -

Samuel R. Delany and the Ecology of Cruising

Queer Fallout Samuel R. Delany and the Ecology of Cruising SARAH ENSOR Department of English Language and Literature & Program in the Environment, University of Michigan, USA Abstract Taking as its provocation Leo Bersani’s fleeting turn to questions of ecology at the end of his 2002 essay “Sociability and Cruising,” thispieceaskswhatitwouldmeantouse the practice of cruising as an unexpected model for a new ecological ethic, one more deeply attuned to our impersonal intimacies with the human, nonhuman, and elemental strang- ers that constitute both our environment and ourselves. In order to develop such a model, the essay looks not only to Bersani’s work but also (and primarily) to Samuel R. Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, whose attention to the positive fallout of spontaneous cross-class contact, I claim, complicates the proprietary, insular, and paranoid logics preva- lent in much popular environmental discourse. Delany’s text, which decenters both intention and identity in its definition of the social, limns the contours of a queer environmentalism pred- icated less on intentional, direct(ed) investment than on ambient affects, impersonal futures, and nonteleological practices of care. Keywords queer ecology, ecocriticism, environmentalism, New Materialism, cruising nthefinal paragraph of his 2002 essay “Sociability and Cruising,” Leo Bersani con- I cludes his discussion of impersonal intimacy and promiscuous attachments with an unexpected turn to ecology: “Let’s call this [ethical model predicated on ascetic prac- tices] an ecological ethics,” he suggests, “one in which the subject, having willed its own lessness, can live less invasively in the world.”1 Cited out of context, there is per- haps little surprising about this statement, particularly its final clause. -

The Tyrannies of Sexual and Gender Normativity Have Been Widely Examined in Queer Theory

robyn wiegman and elizabeth a. wilson Introduction: Antinormativity’s Queer Conventions The tyrannies of sexual and gender normativity have been widely examined in queer theory. Heteronormativity, homonormativity, whiteness, family values, marriage, monogamy, Christmas: all have been objects of sustained critique, producing some of the most important work in the field in the nearly three decades of its formal existence. Indeed, as we read them, nearly every queer theoretical itinerary of analysis that now mat- ters is informed by the prevailing supposition that a critique of normativity marks the spot where queer and theory meet. This special issue of differences unearths the question that lies dormant within this critical code: what might queer theory do if its allegiance to antinormativity was rendered less secure? In the pages that follow, contributors attend to this question by setting their analytic ambitions on the possibility evoked by the title: can queer theorizing proceed without a primary commitment to antinormativity? No one takes this charge to mean that the future of queer theory lies in a disengagement from the question of normativity. On the contrary, we are motivated by the need to know more about the history, social practices, identities, discursive attachments, and political desires that have converged to make normativity Volume 26, Number 1 doi 10.1215/10407391-2880582 © 2015 by Brown University and differences : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/differences/article-pdf/26/1/1/405883/0260001.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 2 Antinormativity’s Queer Conventions queer theory’s axiomatic foe. The provocation offered by our title, then, is less a manifesto than an invitation to think queer theory without assuming a position of antinormativity from the outset. -

ARTICLE Foucault and Sedgwick

Lynne Huffer 2012 ISSN: 1832-5203 Foucault Studies, No. 14, pp. 20-40, September 2012 ARTICLE Foucault and Sedgwick: The Repressive Hypothesis Revisited Lynne Huffer, Emory University ABSTRACT: This essay examines the Foucauldian foundations of queer theory in the work of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. The essay argues that Sedgwick’s increasing disappointment with Foucault’s critique of the repressive hypothesis is in part produced by the slippery rhetoric of The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. Specifically, Foucault’s use of free indirect discourse in that volume destabilizes both the theory of repression and the critique Foucault mounts against it, thereby rendering ambiguous any political promise his critique might seem to offer. Returning to the fraught relation between Foucault and Sedgwick, the essay concludes by reading Foucault and Sedgwick together through the lens of a repa- rative ethics in which the felt experience of knowing the world is also an experiment in new ways of living. Keywords: Sedgwick, repressive hypothesis, free indirect discourse, reparative reading, queer ethics. In my personal life, from the moment of my sexual awakening, I felt excluded, not so much rejected, but belonging to society’s shadow. It’s especially striking as a problem when you discover it for yourself.1 In this rare, unpublished remark from 1975, Foucault describes his own sexual experience of exclusion, marginalization, and queer self-discovery growing up in France in the 1940s and 50s. Given Foucault’s well-known doubts about a repressive hypothesis that conceives of modern sexuality as an inner secret to be hidden or revealed, this archival coming-out story is surprising. -

Gender and Sexuality

Topics in Advanced Performance Studies: Gender and Sexuality Prof. Robin Bernstein Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality (SWGS) 1433 Harvard University Fall 2011, Wednesdays 1-3 pm, Sever Hall 204 Prof. Bernstein’s email: <rbernst@fas> Office: Boylston G31 Office hours: Wednesdays 9-10:30 am Phone: 617.495.9634 This course takes students to the cutting edge of queer theory and performance studies. We engage with three themes that are currently under urgent debate in queer theory: antisociality and utopia, affect and touch, and history and time. As we explore these themes, we ask, where are queer theory and performance studies intersecting—and not? Where and how can we bring them together? What happens when we do so? How might queer theory and performance studies productively challenge each other? Our goal is to form an interpretive community to wrestle with texts that are utterly current—texts whose meanings and implications have not yet been sedimented through repeated acts of reading. Thus we join with reading communities near and far that are also grappling with these recent texts; and we participate in the global project of theorizing queerness and performance. Assignments and requirements: Thoughtful, engaged, and respectful classroom participation 25% Performance Exercises (two exercises, 15% each; various dates) 30% Mid-semester Paper, due Monday, October 3 10% Proposal for Final Project, due November 9 (graded full credit/no credit) 5% Final Project, due Monday, December 12 30% Performance Exercise: In this exercise, you will place our reading in direct conversation with a performance. Students will work in teams of two to bring into the classroom a performance—live or mediated—that relates in some complex way to one or more of the week’s reading assignments. -

How to Bring Your Kids up Gay Author(S): Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Source: Social Text, No

How to Bring Your Kids up Gay Author(s): Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Source: Social Text, No. 29 (1991), pp. 18-27 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/466296 . Accessed: 21/03/2011 16:47 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=duke. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Text. http://www.jstor.org How To Bring Your Kids Up Gay EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK In the summer of 1989, the United States Department of Health and Human Services released a study entitled "Report of the Secretary's Task Force on Youth Suicide." Written in response to the apparently burgeon- ing epidemic of suicides and suicide attempts by children and adolescents in the United States, the 110-page report contained a section analyzing the situation of gay and lesbian youth. -

Full Text (Pdf)

FEMINIST ENCOUNTERS A JOURNAL OF CRITICAL STUDIES IN CULTURE AND POLITICS e-ISSN: 2542-4920 Volume 1, Issue 1 (Autumn 2017) Editor-in-Chief Sally R. Munt Sussex Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Sussex (UK) Guest Editors Salla Peltonen Åbo Akademi University (Finland) Marianne Liljeström University of Turku (Finland) This page intentionally left blank. Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 1(1) ISSN: 2542-4920 CHIEF EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION FEMINIST ENCOUNTERS: A JOURNAL OF CRITICAL STUDIES IN CULTURE AND POLITICS Founded in 2017, Feminist Encounters is a journal committed to argument and debate, in the tradition of historical feminist movements. In the wake of the growing rise of the Right across the world, openly neo-fascist national sentiments, and rising conservative populism, we feminists all over the world are needing to remobilise our energies to protect and advance gender rights. Feminist Encounters provides a forum for feminist theorists, scholars, and activists to communicate with each other, to better educate ourselves on international issues and thus promote more global understanding, and to enhance our critical tools for fighting for human rights. Feminism is an intellectual apparatus, a political agenda, and a programme for social change. Critical analysis of how gender discourses produce cultural identities and social practices within diverse lived realities is key to this change. We need to think more sharply in order to strategise well: as the discourses of conservatism renew and invigorate themselves, so we as feminist scholars need to be refining our amazonic swords in order not just to respond effectively but also to innovate our own ideas for equality and social justice.