Full Text (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBSR 4.1.Indd

volume 4 number 1 summer 2017 Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships james c. wadley, phd, editor Lincoln University jeanine staples, edd, guest editor Penn State University Copyright © 2018 James C. Wadley Th e Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships (JBSR) is a refereed, interdisciplinary, scholarly inquiry devoted to addressing the epistemological, ontological, and social con- struction of sexual expression and relationships of persons within the African diaspora. Th e journal will be used as a medium to capture the functionality and dysfunctionality of individuals, couples, and families as well as the effi cacy in which relationships are nego- tiated. Th e journal seeks to take into account the transhistorical substrates that subsume behavioral, aff ective, and cognitive functioning of persons of African descent as well as those who educate or clinically serve this important population. For additional informa- tion about the JBSR, you can visit Th eJBSR .com, follow us on twitter @Th eJBSR, like our Facebook page, or review current JBSR trends on LinkedIn. Subscriptions Th e Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships (ISSN 2334- 2668) is published quarterly by the University of Nebraska Press. For current subscription rates please see our website: www .nebraskapress .unl .edu. If ordering by mail, please make checks payable to the University of Nebraska Press and send to Th e University of Nebraska Press 1111 Lincoln Mall Lincoln, NE 68588- 0630 Telephone: 402- 472- 8536 submissions Manuscripts should be prepared in 12- point Times New Roman with 1- inch margins. Notes and apparatus must conform to the sixth edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. -

ENGL 261 Advanced Literary Theory

ENGL 261: ADVANCED LITERARY THEORY: QUEER AND POST-QUEER THEORIES OF GENDER, SEXUALITY, AND ABILITY ADAM JOHN WATERMAN FALL 2016 9:30 – 10:45 TR FISK HALL 313 COURSE DESCRIPTION Institutionalized in the 1990s, early queer theory challenged many of the conventions of identitarian-based social formation and political organizing that had characterized gay and lesbian sociality, in the United States, since the 1940s. Drawing on post-structuralist theory, queer theorists sought to explore the processes by which medicalized categories of sexual deviance—where sexual deviance was measured in relation to a wide range of non-reproductive sexual practices—became taken as embodied forms of social and cultural identity. Over time, the scope of queer theory has expanded, such that it now represents a broad range of methodologies by which a host of norms are interrogated and named. Post-queer theory, as such, has left behind its moorings in lesbian and gay studies, to become a mechanism of critique where by theorists explore the sociality of sex, and the sexuality of the social. This course will expose students to a range of works in queer and post-queer theory as part of a larger exploration of methodologies in literary and cultural studies. As fields of scholarship routed through concepts of intersectionality and assemblage, queer and post-queer theories explore the imbrication of race, gender, and sexuality, as well as political economy, the question of disability, and class. REQUIRED TEXTS Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, -

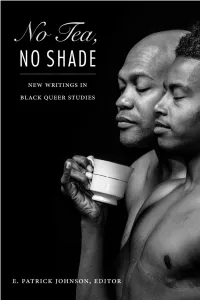

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Let Creativity Happen! Grant 2019 Quarter Four Recipients

Let Creativity Happen! Grant 2019 Quarter Four Recipients 1. Belonging (or not) Abroad By Group Acorde Contemporary Dance and Live Music A collaborative work inspired by Brazilian culture from the perspective of a Brazilian choreographer and dancer residing in Houston for 17 years. As part of The Texas Latino/a Dance Festival, Group Acorde is showcasing the story of its co-director and co-founder Roberta Paixao Cortes through choreography and live music. 2. The Flower Garden of Ignatius Beltran By Adam Castaneda Modern Dance and Literary Arts The Flower Garden of Ignatius Beltran is an original dance work built by the community and performed by the community. This process-based work brings together both professional dancers and non-movers for a process and performance experience that attempts to dismantle the hierarchy and exclusionary practices of Western concert dance. 3. First Annual Texas Latino/a Contemporary Dance Festival By The Pilot Dance Project Modern Dance The Texas Latino/a Contemporary Dance Festival is the first convening of its kind that celebrates the choreographic voices of the Latin American diaspora of Houston. The festival is an initiative to make space for the Latino/a perspective in contemporary dance, and to accentuate the uniqueness of this work. 4. Mommy & Me Pop Up Libraries By Kenisha Coleman Literary Arts Mommy & Me Pop Up Library is a program designed to enrich the lives of mothers and their children through literacy, social engagement, culture, arts, and crafts. We will help to cultivate lifelong skills of learning, comprehension, language, culture, community, and creativity. We will also offer bilingual learning opportunities. -

Black Feminism Reimagined After Intersectionality Jennifer C. Nash

black feminism reimagined after intersectionality jennifer c. nash next wave New Directions in Women’s Studies A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman jennifer c. nash black feminism reimagined after intersectionality Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker and typeset in Whitman and Futura by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Nash, Jennifer C., [date] author. Title: Black feminism reimagined : after intersectionality / Jennifer C. Nash. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018026166 (print) lccn 2018034093 (ebook) isbn 9781478002253 (ebook) isbn 9781478000433 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478000594 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Womanism—United States. | Feminism— United States. | Intersectionality (Sociology) | Feminist theory. | Women’s studies—United States. | Universities and colleges— United States—Sociological aspects. Classification: lcc hq1197 (ebook) | lcc hq1197 .n37 2019 (print) | ddc 305.420973—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026166 cover art: Toyin Ojih Odutola, The Uncertainty Principle, 2014. © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. contents Acknowledgments vii introduction. feeling black feminism 1 1. a love letter from a critic, or notes on the intersectionality wars 33 2. the politics of reading 59 3. surrender 81 4. love in the time of death 111 coda. some of us are tired 133 Notes 139 Bibliography 157 Index 165 acknowledgments Over the course of writing this book, I moved to a new city, started a new job, and welcomed a new life into the world. -

"Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2010 "Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers." James L. Wright UTK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wright, James L., ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers.". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/760 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. Wright entitled ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Suzaanne B. Kurth, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robert Emmet Jones; Hoan Bui; Debora Baldwin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. -

Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Depressives and the Scenes of Queer Writing Allen Durgin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/482 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEPRESSIVES & THE SCENES OF QUEER WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 ALLEN DURGIN All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Robert Reid-Pharr, Chair of Committee Date Mario DiGangi, Executive Officer Wayne Koestenbaum Steven F. Kruger THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT DEPRESSIVES AND THE QUEER SCENES OF WRITING by ALLEN DURGIN Adviser: Professor Robert Reid-Pharr My dissertation attempts to answer the question: What exactly does a reparative reading look like? The question refers to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s provocative essay on paranoid and reparative reading practices, in which Sedgwick describes how the hermeneutics of suspicion has become central to a whole range of intellectual projects across the humanities and social sciences. Criticizing this dominant critical mode for its political blindness and unintended replication of repressive social structures, Sedgwick looks for an alternative in what she calls reparative reading. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

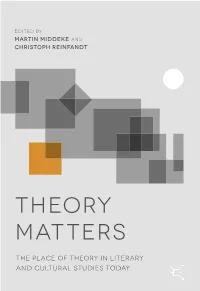

Theory Matters

Edited by Martin Middeke and Christoph Reinfandt Theory Matters The Place of Theory in Literary and Cultural Studies Today Theory Matters Martin Middeke • Christoph Reinfandt Editors Theory Matters The Place of Theory in Literary and Cultural Studies Today Editors Martin Middeke Christoph Reinfandt Chair of English Literature Chair of English Literature University of Augsburg University of Tübingen Augsburg , Germany Tübingen , Germany ISBN 978-1-137-47427-8 ISBN 978-1-137-47428-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-47428-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016942080 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

A Few Lies: Queer Theory and Our Method Melodramas David Kurnick

A Few Lies: Queer Theory and Our Method Melodramas David Kurnick ELH, Volume 87, Number 2, Summer 2020, pp. 349-374 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/elh.2020.0011 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/757342 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] A FEW LIES: QUEER THEORY AND OUR METHOD MELODRAMAS BY DAVID KURNICK “We have been telling a few lies”: the words mark the end of what we could call the overture of Leo Bersani’s 1987 essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?”1 The lies Bersani is referring to are, in the first place, the dignifying fantasies gay male activists have spun about the necessarily liberatory consequences of same-sex attraction. Right-wing politics, he has just reminded us, consort quite nicely with some men’s “marked sexual preference for sailors and telephone linemen.”2 He is about to tear off into what for some of us, more than thirty years later, remains a famous rebuttal of Dennis Altman’s claims for the gay bathhouse as a space of Whitmanian democracy. Bersani begs to differ: “Your looks, muscles, hair distribution, size of cock, and shape of ass determined exactly how happy you were going to be during those few hours[.]”3 Such deflationary rhetoric is, of course, one of Bersani’s hallmarks. But he’s not alone in it. In fact, uncomfortable truth-telling constitutes a central tradition in what we have for a while been calling queer culture. -

Eve Kosofiky Sedgwick

TENDENCIES EDITED BY MICHELE AINA BARALE, JONATHAN GOLDBERG, MICHAEL MOON, AND EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK Eve Kosofiky Sedgwick DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham 1993 Second printing, 1994 © 1993 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper @ Typeset in Sabon by Tseng Information Systems Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. "Queer and Now" first appeared in Mark Edmund son, ed., Wild Orchids and Trotsky: Messages from American Universities (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), pp. 237-66, © 1993 by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. "Privilege of Unknowing" previously appeared in Gen ders 1 (Spring 1988): 102-24, and is reprinted by permission. "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" first appeared in Critical Inquiry 17.4 (Summer 1991): 818-37, © 1991 by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. t "Epidemics of the Will" previously appeared in Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter, ecls., Incorporations (New York: Zone, 1992), pp. 582-95, and is reprinted by permission. "Nationalisms and Sexualities" previously appeared in Andrew Parker, Mary Russo, Doris Sommer, and Patricia Yaeger, eds., Nationalisms and Sexualities (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 235-45, and is re printed by permission. "How to Bring Your Kids Up Gay" first appeared in Social Text 29 (1991): 18-27, © 1991 by Social Text, and is reprinted by permission. "Willa Cather and Others" first appeared as "Across Gender, Across Sexuality: Willa Cather and Others," in South Atlantic Quarterly 88.1 (Winter 1989): 53 72, © 1989 by Duke University Press. "A Poem Is Being Written" previously appeared in Representations 17 (Winter 1987): 110-43, © 1987 by the Regents of the University of California, and is re printed by permission.