Physical Abuse 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traumatic Brain Injury(Tbi)

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY(TBI) B.K NANDA, LECTURER(PHYSIOTHERAPY) S. K. HALDAR, SR. OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST CUM JR. LECTURER What is Traumatic Brain injury? Traumatic brain injury is defined as damage to the brain resulting from external mechanical force, such as rapid acceleration or deceleration impact, blast waves, or penetration by a projectile, leading to temporary or permanent impairment of brain function. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has a dramatic impact on the health of the nation: it accounts for 15–20% of deaths in people aged 5–35 yr old, and is responsible for 1% of all adult deaths. TBI is a major cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in children and young adults. Males sustain traumatic brain injuries more frequently than do females. Approximately 1.4 million people in the UK suffer a head injury every year, resulting in nearly 150 000 hospital admissions per year. Of these, approximately 3500 patients require admission to ICU. The overall mortality in severe TBI, defined as a post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤8, is 23%. In addition to the high mortality, approximately 60% of survivors have significant ongoing deficits including cognitive competency, major activity, and leisure and recreation. This has a severe financial, emotional, and social impact on survivors left with lifelong disability and on their families. It is well established that the major determinant of outcome from TBI is the severity of the primary injury, which is irreversible. However, secondary injury, primarily cerebral ischaemia, occurring in the post-injury phase, may be due to intracranial hypertension, systemic hypotension, hypoxia, hyperpyrexia, hypocapnia and hypoglycaemia, all of which have been shown to independently worsen survival after TBI. -

MDS Round-Up 2018! Ronald Orth, RN, CHC, CMAC September 2018

MDS Round-Up 2018! Ronald Orth, RN, CHC, CMAC September 2018 Presented by Presenter • Ronald Orth, RN, CMAC, CHC obtained a nursing degree from Milwaukee Area Technical College in 1985 and a B. A. in Health Care Administration from Concordia University in 1996. Mr. Orth possess over 30 years of nursing experience with over 20 of those in the Skilled Nursing industry. Mr. Orth has extensive experience in teaching Medicare regulations to healthcare providers both in the US and internationally. Mr. Orth is currently the Senior SNF Regulatory Analyst at Relias Learning and is certified in Healthcare Compliance through the Compliance Certification Board (CCB). Ron is also an approved ICD-10-CM trainer with AHIMA. 2 Interview Clarifications Timing of Interviews • Section C (BIMS) – Conducted during the 7 day lookback period, preferably on the ARD or the day before. • Section D (PHQ-9) - Conducted during the 7-day lookback period. Preferably on the ARD or the day before. • Section F (Activities/Preferences) – During the 7-day lookback period. • Section J (Pain) – Conducted anytime during the 5-day lookback period. It is PREFERRED to conduct on the ARD or the day before. 3 Interview Clarifications • Applies to all interview sections • Section C – BIMS • Section D – PHQ-9 • Section F – Activities and Preferences • Section J – Pain • Staff interview should not be completed in place of resident interview if the resident interview should have been completed. • Answer “Gateway” question as “yes” • Dash interview items • B0700 should NOT be coded as “Rarely/Never Understood” if any of the resident interviews were completed. 4 Section I New Item – I0020 • Resident’s primary medical condition • Provides check boxes for 14 different items 5 Section I • Select the condition that represents the primary condition that resulted in resident’s admission to the nursing facility. -

Assessment of the Severity of Head Injury

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.39.7.647 on 1 July 1976. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, andPsychiatry, 1976, 39, 647-655 Assessment of the severity of head injury BRYAN JENNETT From the University Department of Neurosurgery, Institute of Neurological Sciences, Glasgow SYNOPSIS Ranking of head injuries by severity is an essential part of clinical management, of prognosis, oftreatment trials, and oflegal assessment for compensation. Various methods ofassessing severity are reviewed. No one scale is appropriate for all types of injury, or in all circumstances. A check list is provided which should enable every injury to be assessed; its use would facilitate comparison between individual cases of head injury, and between reports from different studies. 'Head injury' is used much more commonly than skull, and there is only a possibility ofintracranial the several rubrics of the International Classifica- complications. This accounts for classifications Protected by copyright. tion of Disease (ICD) which it encompasses; yet based on aposteriori evidence-deciding that the the term itself is not recognized as an entity in injury was not severe because the patient has this classification. In practice it can embrace all made a good recovery. Contemporary concepts degrees of severity from a symptomless bump to of the pathological basis of milder injuries have a blow which causes overwhelming brain damage. exposed the fundamental fallacy ofthis argument, Yet what is necessary for an incident to qualify in that mild concussion is now believed to produce as a head injury is by no means self-evident. Such permanent brain damage, albeit of a minor minimum requirements must indeed be arbitrary degree. -

MDS 3.0 Updates 2018

MDS 3.0 Updates 2018 Cassie Crafton R.N., CDP, RAC-CT Objectives • Understand new MDS 3.0 items in Sections GG, I, J, M, N and O that will be effective October 1st, 2018 • Know which MDS 3.0 items that will be removed and language changes Clarifications with Resident Interviews Timing of Interviews • Section C (BIMS)- to be conducted preferably on the ARD or the day before • Section D (PHQ-9)- to be conducted preferably on the ARD or the day before • Section F (Activities/Preferences)- during the 7 day look back period • Section J (Pain)- to be conducted anytime during the 5 day lookback period preferably on the ARD or the day before Clarifications with Resident Interviews • Staff interview should not be completed in place of resident interview IF the resident interview could have been completed • B0700 should NOT be coded as “Rarely/Never Understood” if any of the resident interviews were completed PPS Changes • Section GG changes • Admission and Discharge Assessments • Language Changes Coding Tips • Admission Performance and Discharge Goals are coded on every Admission Assessment (Start of Part A PPS Stay) regardless of length of stay and planned or unplanned discharge • If the resident has an incomplete stay: – Complete admission performance and goals – Discharge self-care and mobility performance items are not required Section GG- Intent • Functional status is assessed based on the need for assistance when performing self - care and mobility activities • Residents in SNFs have self - care and mobility limitations and are at risk for -

Appendix 1. ICD-9-CM Codes for Defining Non-Fatal Abusive Head Trauma in Children Under the Age of 5 Years Code Meaning 361.00 R

Appendix 1. ICD-9-CM Codes for Defining Non-Fatal Abusive Head Trauma in Children under the Age of 5 Years Code Meaning 361.00 Retinal detachment with retinal defect, unspecified 361.01 Recent detachment, partial, with single defect 361.02 Recent detachment, partial, with multiple defects 361.03 Recent detachment, partial, with giant tear 361.04 Recent detachment, partial, with retinal dialysis 361.05 Recent detachment, total or subtotal 361.10 Retinoschisis, unspecified 361.30 Retinal defect, unspecified 361.33 Multiple defects of retina without detachment 361.8 Retinal detachments and defects- other forms of retinal detachment 361.81 Traction detachment of retina 361.89 Other - Traction detachment with vitreoretinal organization 361.9 Unspecified retinal detachment 362.40 Retinal layer separation, unspecified 362.81 Retinal hemorrhage 780.0 General symptoms- alteration of consciousness 780.01 Coma 780.02 Transient alteration of awareness 780.03 Persistent vegetative state 780.09 Other 780.39 Other convulsions 781.0 Abnormal involuntary movements 781.1 Disturbances of sensation of smell and taste 781.2 Abnormality of gait 781.3 Lack of coordination 781.4 Transient paralysis of limb 781.8 Neurologic neglect syndrome 800.0 Fracture of vault of skull- Closed without mention of intracranial injury 800.00 Closed without mention of intracranial injury- unspecified state of consciousness 800.01 Closed without mention of intracranial injury- with no loss of consciousness 800.02 Closed without mention of intracranial injury- with brief [less -

Useful Markers to Assess Traumatic and Hypoxic Brain Injury

Rom J Leg Med [25] 146-151 [2017] DOI: 10.4323/rjlm.2017.146 © 2017 Romanian Society of Legal Medicine FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH Useful markers to assess traumatic and hypoxic brain injury Violeta Ionela Chirica1,* _________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Traumatic Brain Injury, TBI, is a very important health issue world wide. Many traumatic events are not witnessed and not declared, especially in mild TBI, mTBI, and therefore not known, not treated or cured. At autopsy the diagnosis of brain injury is in many cases a challenge especially in children with physical abuse. Quite often the judicial system ask for scientific proofs of objectivity in determining the cause of death in head trauma. Sometimes legal medicine is called to determine the extent of the brain injuries following anoxia or hypoxia after a CA resuscitated. Pathology and anatomic pathology sometimes may offer important clues for diagnosis but often there are time consuming. The use of biomarkers in predictive way for prognosis and for diagnosis is a very potent and useful tool in legal medicine. Some of the brain injury biomarkers express the integrity of neurons or neurologic network, including astrocytes, and therefore express the structural integrity of the nervous system. The cutoff limit of these markers is in scientific debates and legal medicine may offer a support for their research. Some biomarkers are studied and presented such as biofluid biomarkers of astroglial injury, S100Beta, Glial Fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), biofluid biomarkers of neuronal injury, Neuron-specific enolase (NSE), Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1), CK0BB, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF, Biofluid biomarkers of axonal injury, Alpha-II spectrin, Tau protein, Neurofilaments, N-Cam or selectins. -

Cannabidiol (CBD)

Sports Injuries and Medicine Reillo MR & Levin I Sports Injr Med 03: JSIMD-158. Review Article DOI: 10.29011/2576-9596.100058 Cannabidiol (CBD) in the Management of Sports-Related Traumatic Brain Injury: Research and Efficacy Michele R Reillo*, Ian Levin University, Cannabis Academy, Ontario, Canada *Corresponding author: Michele R Reillo, University, Cannabis Academy, Ontario, Canada. Email: [email protected] Citation: Reillo MR, Levin I (2019) Cannabidiol (CBD) in the Management of Sports-Related Traumatic Brain Injury: Research and Efficacy. Sports Injr Med 03: 158. DOI: 10.29011/2576-9596.100058 Received Date: 15 October 2019; Accepted Date: 25 October 2019; Published Date: 30 October 2019 Introduction receptors in the brain, regulates the vast array of physiological processes essential for human life [1,2]. The pandemic of sports-related traumatic brain injury and the associated development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy The Human Endocannabinoid System has prompted an interest within the medical community in the role The human endocannabinoid system is responsible for of the endocannabinoid system and the use of Cannabidiol (CBD) memory networks in the brain, both excitatory and inhibitory, to reduce acute and chronic cerebral inflammation among athletes. including the neurogenesis of hippocampal granule cells, which The purpose of this medical research review is to examine sports- regulate the timing of the endocannabinoids in accordance with related traumatic brain injury and the preventative and therapeutic the brain’s needs, pain perception, mood, synaptic plasticity, motor use of cannabidiol among athletes. Given the high morbidity and learning, appetite and taste regulation, and metabolic function, which mortality rate associated with post- concussion syndrome and regulates the storage of energy and transport of cellular nutrition. -

Pathophysiological and Behavioral Deficits in Developing Mice Following

Pathophysiological and behavioral deficits in developing mice following ... https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5818073/?report=printable Dis Model Mech. 2018 Jan 1; 11(1): dmm030387. PMCID: PMC5818073 doi: 10.1242/dmm.030387 PMID: 29208736 Pathophysiological and behavioral deficits in developing mice following rotational acceleration-deceleration traumatic brain injury Guoxiang Wang,1,2Yi Ping Zhang, 3Zhongwen Gao, 2,4Lisa B. E. Shields, 3Fang Li, 2,5Tianci Chu, 2Huayi Lv, 6 Thomas Moriarty,3Xiao-Ming Xu, 7Xiaoyu Yang, 1,*Christopher B. Shields, 3,8,* and Jun Cai 1,2,9,* 1 Department of Spine Surgery, Orthopedics Hospital affiliated to the Second Bethune Hospital, Jilin University, Changchun 130041, China 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40202, USA 3Norton Neuroscience Institute, Norton Healthcare, Louisville, KY 40202, USA 4Department of Orthopedics, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130033, China 5Department of Neurological Surgery, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing 100029, China 6 Eye Center of the Second Bethune Hospital, Jilin University, Changchun 130041, China 7Stark Neurosciences Research Institute, Department of Neurological Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA 8Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40202, USA 9Department of Anatomical Sciences and Neurobiology, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40202, USA * Authors for correspondence ([email protected] ;[email protected] ;[email protected]) Received 2017 Apr 27; Accepted 2017 Nov 16. Copyright © 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses /by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed. -

Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury with and Without Loss of Consciousness with Dementia in US Military Veterans

Supplementary Online Content Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC, Seal KH, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K. Association of mild traumatic brain injury with and without loss of consciousness with dementia in US military veterans. Published online May 7, 2018. JAMA Neurol. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0815. eAppendix 1. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Severity Case Definitions. eAppendix 2. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Severity Classification Using Modified Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) 2012 ICD-9 Diagnostic Code List. eAppendix 3. Dementia ICD-9 Diagnostic Code List. eTable. Traumatic Brain Injury Case Distribution. This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eAppendix 1. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Severity Case Definitions TBI Severity Data Mild, Mild, Mild, Moderate/Severe Source Without LOC With LOC LOC Unknown CTBIE LOC = 0; LOC > 0 to 30 min; N/A LOC > 30 min; AOC = a moment to 24 hrs; AOC = a moment to 24 hrs; AOC > 24 hours; AND PTA 0 to 1 day AND PTA 0 to 1 day OR PTA > 1 day NPCD Mild TBI (ICD-9 codes); Mild TBI (ICD-9 codes); Mild TBI (ICD-9 codes); Moderate, Severe or AND LOC = 0 AND LOC = brief (< 1 hr) AND LOC = unknown Penetrating TBI (ICD-9 or unspecified codes) CTBIE, Comprehensive Traumatic Brain Injury Evaluation; AOC, alteration of consciousness; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases – 9th edition; LOC, loss of consciousness; NPCD, National Patient Care Database; PTA, post-traumatic amnesia. -

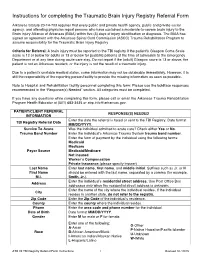

Instructions for Completing the Traumatic Brain Injury Registry Referral Form

Instructions for completing the Traumatic Brain Injury Registry Referral Form Arkansas Statute 20-14-703 requires that every public and private health agency, public and private social agency, and attending physician report persons who have sustained a moderate-to-severe brain injury to the Brain Injury Alliance of Arkansas (BIAA) within five (5) days of injury identification or diagnosis. The BIAA has signed an agreement with the Arkansas Spinal Cord Commission (ASCC) Trauma Rehabilitation Program to assume responsibility for the Traumatic Brain Injury Registry. Criteria for Referral: A brain injury must be reported to the TBI registry if the patient's Glasgow Coma Scale score is 12 or below for adults or 13 or below for pediatric patients at the time of admission to the Emergency Department or at any time during acute care stay. Do not report if the (adult) Glasgow score is 13 or above, the patient is not an Arkansas resident, or the injury is not the result of a traumatic injury. Due to a patient’s unstable medical status, some information may not be obtainable immediately. However, it is still the responsibility of the reporting person/facility to provide the missing information as soon as possible. Note to Hospital and Rehabilitation facility personnel completing this form: Please use the boldface responses recommended in the “Response(s) Needed” section. All categories must be completed. If you have any questions while completing this form, please call or email the Arkansas Trauma Rehabilitation Program Health Educator at (501) 683-3435 or [email protected]. PATIENT/CLIENT REFERRAL RESPONSE(S) NEEDED INFORMATION Enter the date the referral is faxed or sent to the TBI Registry. -

Medical Policy Outpatient Cognitive Rehabilitation

Medical Policy Outpatient Cognitive Rehabilitation Table of Contents Policy: Commercial Coding Information Information Pertaining to All Policies Policy: Medicare Description References Authorization Information Policy History Policy Number: 660 BCBSA Reference Number: 8.03.10 Related Policies Sensory Integration Therapy, #659 Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Medicare HMO BlueSM and Medicare PPO BlueSM Members Outpatient cognitive rehabilitation (as a distinct and definable component of the rehabilitation process) may be MEDICALLY NECESSARY in the rehabilitation of patients with traumatic brain injury. Outpatient cognitive rehabilitation (as a distinct and definable component of the rehabilitation process) is INVESTIGATIONAL for all applications, including, but not limited to, stroke, post-encephalitic or post- encephalopathy patients, autism spectrum disorders, seizure disorders, and the aging population, including Alzheimer’s patients. Prior Authorization Information Pre-service approval is required for all inpatient services for all products. See below for situations where prior authorization may be required or may not be required for outpatient services. Yes indicates that prior authorization is required. No indicates that prior authorization is not required. Outpatient Commercial Managed Care (HMO and POS) No Commercial PPO and Indemnity No Medicare HMO BlueSM No Medicare PPO BlueSM No 1 CPT Codes / HCPCS Codes / ICD-9 Codes The following codes are included below for informational -

Postnatal and Perinatal Trauma. Following Two Introductory

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 047 452 EC 031 5g4 AUTHOR Angle, Carol R., Ed.; Bering, Edgar A., Jr., Pd. TITLE Physical Trauma as an Etiological Agent in Mental Retardation. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. (DHEW) , Bethesda, Md.; Nebraska Univ., Lincoln. Coll. of Medicine. PUB DATE 70. NOTE 311p.; Proceedings of a Conference on the Etiology of Mental Retardation (Omaha, Nebraska, October 13-16, 1968) AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 ($3.75) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Conference Reports, Etiology, *Exceptional Child Research, Incidence, *Infancy, *Injuries, *Medical Research, *Mental Retardation, Neurological Organization, Neurology, Pathology, Premature Infants, Prenatal Influences IDENTIFIERS Pediatrics ABSTRACT The conference on Physical Trauma as a Cause of Mental Retardation dealt with two major areas of etiological concern - postnatal and perinatal trauma. Following two introductory statements on the problem of and issues related to mental retardation (MR) after early trauma to the brain, five papers on the epidemiology of head trauma cover pathological aspects, terminal hemorrhages in the brain wall of neonates, postmortem neuropathologic findings in birth-injured patients, and epidemiological studies. Nine papers report perinatal studies on such topics as obstetric history, obstetric trauma, fetal head position, maternal pelvic size, birth position, intrapartum uterine contractions, and related fetal head compression and heart rate changes. Five special studies of the developing brain concern trauma during labor, trauma to neck vessels, the immature train's reaction to injury, partial brain removal in infant rats, and cerebral ablation in infant monkeys. The following aspects of the premature infant are discussed in relation to MR in five papers: intracranial hemorrhage, CNS damage, clinical evaluation, EEG and subsequent development, and hematologic factors.