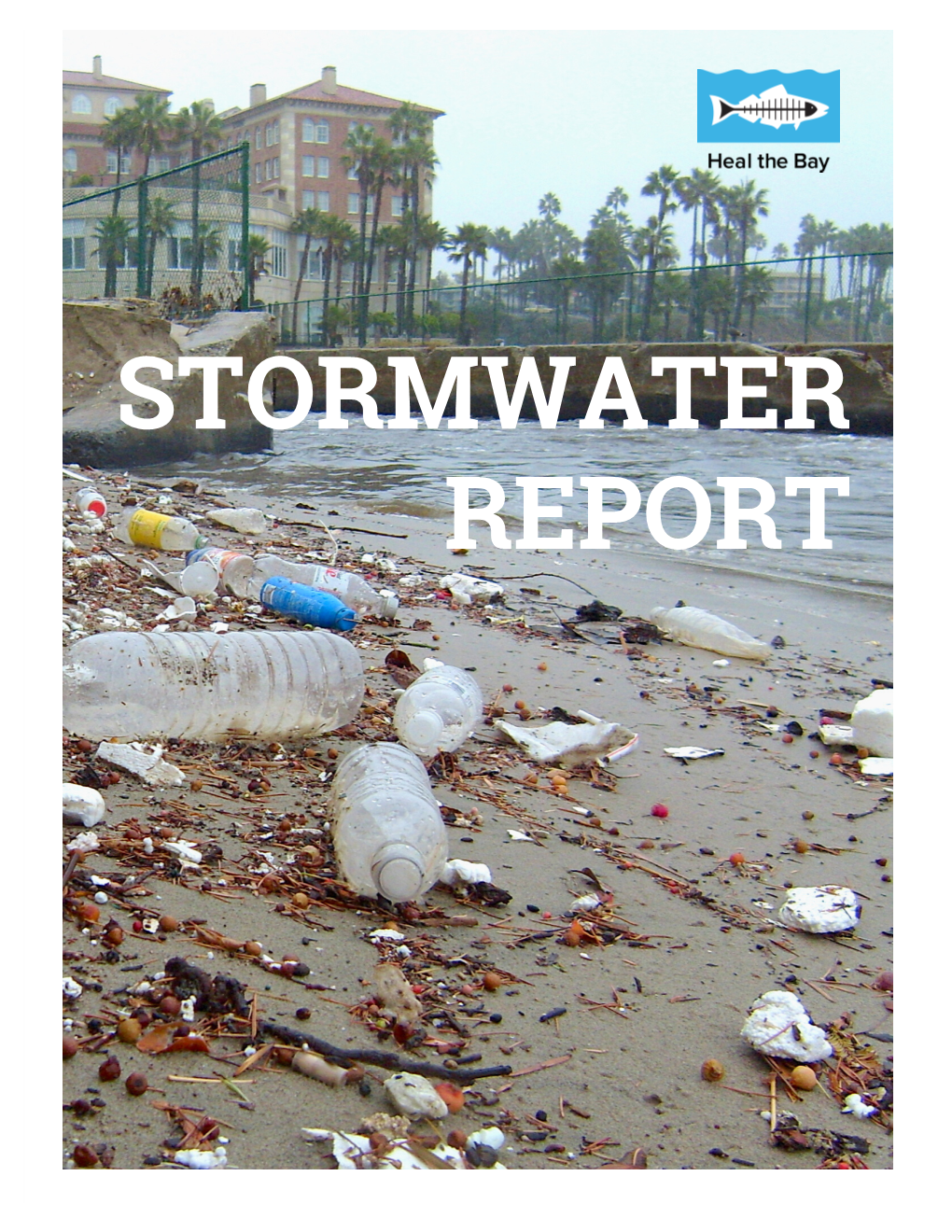

Stormwater Report Stormwater Report Acronyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facts About the Malibu Lagoon Restoration and Enhancement Plan

FACTS ABOUT THE MALIBU LAGOON RESTORATION AND ENHANCEMENT PLAN The project is not intended to “clean up” the water quality for recreation, but it will have water quality benefits for the aquatic ecosystem. The lagoon is not healthy • The lagoon is listed on the federal 303(d) list of impaired water bodies, due to excess nutrients and low oxygen levels. • Data collected continuously since 2006 show oxygen levels are frequently below 5 mg per liter, a level that causes stress to aquatic organisms. • Excess nutrients and bacteria attach to fine sediments that settle on the bottom of the channels. • The excess sedimentation is due to poor circulation. • The poor circulation is caused by the pinch points of fill that support the pedestrian bridges, and by the unnatural alignment of the channels, perpendicular to the main lagoon channel. The only way to correct the poor circulation is to remove old fill and reconfigure the channels to a more natural pattern. • The three channels will be reconfigured into a single branched channel that angles towards the ocean. • A single branched channel will cause the water to move faster and will help prevent excess sedimentation. This is similar to the Venturi effect, where the velocity of a fluid increases as the cross section of the tube carrying it decreases. The work will occur only in the western channels and the Adamson boat house channel, not in the main body of the lagoon. • The sand berm beach will not be changed. • The surf break will not be impacted. • The location of the breach and the timing of breaches will not change. -

Hydrology and Water Quality Modeling of the Santa Monica Bay Watershed

JULY 2009 19. Hydrology and Water Quality Modeling of the Santa Monica Bay Watershed Jingfen Sheng John P. Wilson Acknowledgements: Financial support for this work was provided by the San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy, as part of the “Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California” Project. The authors thank Jennifer Wolch for her comments and edits on this paper. The authors would also like to thank Eric Stein, Drew Ackerman, Ken Hoffman, Wing Tam, and Betty Dong for their timely advice and encouragement. Prepared for: San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy 100 N. Old San Gabriel Canyon Road Azusa, CA 91702. Preferred Citation: Sheng, J., and Wilson, J.P., 2009. The Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California: 18, Hydrology and Water Quality Modeling for the Santa Monica Bay Watershed. University of Southern California GIS Research Laboratory, Los Angeles, California. This report was printed on recycled paper. The mission of the Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California is to offer a guide to habitat conservation, watershed health and recreational open space for the Los Angeles metropolitan region. The Plan will also provide decision support tools to nurture a living green matrix for southern California. Our goals are to protect and restore natural areas, restore natural hydrological function, promote equitable access to open space, and maximize support via multiple-use facilities. The Plan is a joint venture between the University of Southern California and the San Gabriel and lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy, Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Coastal Conservancy, and Baldwin Hills Conservancy. -

Santa Monica Beach Restoration Pilot Project

Santa Monica Beach Restoration Pilot Project Year 3 Annual Report September 2019 Prepared for: City of Santa Monica California Coastal Commission US Environmental Protection Agency California Department of Parks and Recreation The Bay Foundation 8334 Lincoln Blvd. #310 (888) 301-2527 www.santamonicabay.org Year 3 Annual Report, September 2019 Santa Monica Beach Restoration Pilot Project Year 3 Annual Report September 2019 Prepared by: The Bay Foundation Prepared for: City of Santa Monica, California Coastal Commission, US Environmental Protection Agency, California Department of Parks and Recreation Authors: Karina Johnston, Melodie Grubbs, and Chris Enyart, The Bay Foundation Scientific Contributors: David Hubbard, University of California Santa Barbara Dr. Jenifer Dugan, University of California Santa Barbara Dan Cooper, Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc. Dr. Karen Martin, Pepperdine University Dr. Sean Anderson, California State University Channel Islands Dr. Guangyu Wang, Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission Evyan Sloane, California State Coastal Conservancy Suggested Citation: Johnston, K., M. Grubbs, and C. Enyart. 2019. Santa Monica Beach Restoration Pilot Project: Year 3 Annual Report. Report prepared by The Bay Foundation for City of Santa Monica, California Coastal Commission, US Environmental Protection Agency, and California Department of Parks and Recreation. 88 pages. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Metabolic Studio (Annenberg Foundation; Grant 15-541) for funding the implementation of this pilot project, and our partners: City of Santa Monica and California Department of Parks and Recreation. Their support has allowed us to explore soft-scape protection measures to increase coastal resilience, while bringing back an important coastal habitat to the Los Angeles region. -

Land Use Element Designates the General Distribution and Location Patterns of Such Uses As Housing, Business, Industry, and Open Space

CIRCULATION ELEMENT CITY OF HAWTHORNE GENERAL PLAN Adopted April, 1990 Prepared by: Cotton/Beland/Associates, Inc. 1028 North Lake Avenue, Suite 107 Pasadena, California 91104 Revision Table Date Case # Resolution # 07/23/2001 2001GP01 6675 06/28/2005 2005GP03 & 04 6967 12/09/2008 2008GP03 7221 06/26/2012 2012GP01 7466 12/04/2015 2015GP02 7751 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. Introduction to the Circulation Element 1 Purpose of this Element 1 Relation to Other General Plan Elements 1 II. Existing Conditions 2 Freeways 2 Local Vehicular Circulation and Street Classification 3 Transit Systems 4 Para-transit Systems 6 Transportation System Management 6 TSM Strategies 7 Non-motorized Circulation 7 Other Circulation Related Topics 8 III. Issues and Opportunities 10 IV. Circulation Element Goals and Policies 11 V. Crenshaw Station Active Transportation Plan 23 Circulation Element March 1989 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Figure1: Street Classification 17 Figure 2: Traffic Volume Map 18 Figure 3: Roadway Standards 19 Figure 4: Truck Routes 20 Figure 5: Level of Service 21 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Definitions of Level-of-Service 22 Circulation Element March 1989 SECTION I - INTRODUCTION TO THE CIRCULATION ELEMENT Circulation and transportation systems are one of the most important of all urban systems in determining the overall structure and form of the areas they service. The basic purpose of a transportation network within the City of Hawthorne is the provision of an efficient, safe, and serviceable framework which enables people to move among various sections of the city in order to work, shop, or spend leisure hours. -

16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report

16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report Jingfen Sheng John P. Wilson Acknowledgements: Financial support for this work was provided by the San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy and the County of Los Angeles, as part of the “Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California” Project. The authors thank Jennifer Wolch for her comments and edits on this report. The authors would also like to thank Frank Simpson for his input on this report. Prepared for: San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy 900 South Fremont Avenue, Alhambra, California 91802-1460 Photography: Cover, left to right: Arroyo Simi within the city of Moorpark (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng); eastern Calleguas Creek Watershed tributaries, classifi ed by Strahler stream order (Jingfen Sheng); Morris Dam (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng). All in-text photos are credited to Jaime Sayre/ Jingfen Sheng, with the exceptions of Photo 4.6 (http://www.you-are- here.com/location/la_river.html) and Photo 4.7 (digital-library.csun.edu/ cdm4/browse.php?...). Preferred Citation: Sheng, J. and Wilson, J.P. 2008. The Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California. 16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report. University of Southern California GIS Research Laboratory and Center for Sustainable Cities, Los Angeles, California. This report was printed on recycled paper. The mission of the Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California is to offer a guide to habitat conservation, watershed health and recreational open space for the Los Angeles metropolitan region. The Plan will also provide decision support tools to nurture a living green matrix for southern California. -

Watershed Summaries

Appendix A: Watershed Summaries Preface California’s watersheds supply water for drinking, recreation, industry, and farming and at the same time provide critical habitat for a wide variety of animal species. Conceptually, a watershed is any sloping surface that sheds water, such as a creek, lake, slough or estuary. In southern California, rapid population growth in watersheds has led to increased conflict between human users of natural resources, dramatic loss of native diversity, and a general decline in the health of ecosystems. California ranks second in the country in the number of listed endangered and threatened aquatic species. This Appendix is a “working” database that can be supplemented in the future. It provides a brief overview of information on the major hydrological units of the South Coast, and draws from the following primary sources: • The California Rivers Assessment (CARA) database (http://www.ice.ucdavis.edu/newcara) provides information on large-scale watershed and river basin statistics; • Information on the creeks and watersheds for the ESU of the endangered southern steelhead trout from the National Marine Fisheries Service (http://swr.ucsd.edu/hcd/SoCalDistrib.htm); • Watershed Plans from the Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCB) that provide summaries of existing hydrological units for each subregion of the south coast (http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/rwqcbs/index.html); • General information on the ecology of the rivers and watersheds of the south coast described in California’s Rivers and Streams: Working -

Southern Steelhead Populations Are in Danger of Extinction Within the Next 25-50 Years, Due to Anthropogenic and Environmental Impacts That Threaten Recovery

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA STEELHEAD Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus Critical Concern. Status Score = 1.9 out of 5.0. Southern steelhead populations are in danger of extinction within the next 25-50 years, due to anthropogenic and environmental impacts that threaten recovery. Since its listing as an Endangered Species in 1997, southern steelhead abundance remains precariously low. Description: Southern steelhead are similar to other steelhead and are distinguished primarily by genetic and physiological differences that reflect their evolutionary history. They also exhibit morphometric differences that distinguish them from other coastal steelhead in California such as longer, more streamlined bodies that facilitate passage more easily in Southern California’s characteristic low flow, flashy streams (Bajjaliya et al. 2014). Taxonomic Relationships: Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) historically populated all coastal streams of Southern California with permanent flows, as either resident or anadromous trout, or both. Due to natural events such as fire and debris flows, and more recently due to anthropogenic forces such as urbanization and dam construction, many rainbow trout populations are isolated in remote headwaters of their native basins and exhibit a resident life history. In streams with access to the ocean, anadromous forms are present, which have a complex relationship with the resident forms (see Life History section). Southern California steelhead, or southern steelhead, is our informal name for the anadromous form of the formally designated Southern California Coast Steelhead Distinct Population Segment (DPS). Southern steelhead occurring below man-made or natural barriers were distinguished from resident trout in the Endangered Species Act (ESA) listing, and are under different jurisdictions for purposes of fisheries management although the two forms typically constitute one interbreeding population. -

Index of Surface-Water Records

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 72 January 1950 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PART 11.PPACIFIC SLOPE BASINS IN CALIFORNIA TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1948 Prepared by San Francisco District UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director WASHINGTON, D. C. Free on application to the Director, Geological Survey, Washington 26, D. C. INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PART 11.PPACIFIC SLOPE BASINS IN CALIFORNIA TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1948 EXPLANATION The index lists the stream-flow ana reservoir stations in the Pacific Slope Basins in California for which records have been or are to be pub lished for periods prior to September 30, 1948. The stations are listed in downstream order. Tributary streams are indicated by indention. Station names are given in their most recently published forms. Paren theses around part of a station name indicate that the enclosed word or words were used in an earlier published name of the station or in a name under which records were published by some agency other than the Geological Survey. The drainage areas, in square miles, are the latest figures published or otherwise available at this time. Drainage areas that were obviously inconsistent with other drainage areas on the same stream have been omitted. Some drainage areas not published by the Geological Survey are listed with an appropriate footnote stating the published source of the figure of drainage area. Under "period of record" breaks of less than a 12-month period are not shown. A dash not followed immediately by a closing date shows that the station was in operation on September 30, 1948. -

Los Angeles County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Los Angeles County Arroyo Sequit Arroyo Sequit consists of about 3.3 stream miles. The arroyo is formed by the confluence of the East and West forks, from where it flows south to enter the Pacific Ocean east of Sequit Point. As part of a survey of 32 southern coastal watersheds, Arroyo Sequit was surveyed in 1979. The O. mykiss sampled were between about two and 6.5 inches in length. The survey report states, “Historically, small steelhead runs have been reported in this area” (DFG 1980). It also recommends, “…future upstream water demands and construction should be reviewed to insure that riparian and aquatic habitats are maintained” (DFG 1980). Arroyo Sequit was surveyed in 1989-1990 as part of a study of six streams originating in the Santa Monta Mountains. The resulting report indicates the presence of steelhead and states, “Low streamflows are presently limiting fish habitat, particularly adult habitat, and potential fish passage problems exist…” (Keegan 1990a, p. 3-4). Staff from DFG surveyed Arroyo Sequit in 1993 and captured O. mykiss, taking scale and fin samples for analysis. The individuals ranged in length between about 7.7 and 11.6 inches (DFG 1993). As reported in a distribution study, a 15-17 inch trout was observed in March 2000 in Arroyo Sequit (Dagit 2005). Staff from NMFS surveyed Arroyo Sequit in 2002 as part of a study of steelhead distribution. An adult steelhead was observed during sampling (NMFS 2002a). Additional documentation of steelhead using the creek between 2000-2007 was provided by Dagit et al. -

3.7 Hydrology and Water Quality

3.7 – HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY 3.7 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY This section describes the existing setting of the project site and vicinity, identifies associated regulatory requirements, and evaluates potential impacts related to construction and operation of the proposed project. Documents reviewed and incorporated as part of this analysis include the Civil Engineering Initial Study Data (KPFF Consulting Engineers, August 2016, Appendix G), the Sewer Capacity Study (KPFF Consulting Engineers, June 2016, Appendix G), the Geotechnical Engineering Investigation – Proposed Robertson Lane Hotel and Retail Structures, and Subterranean Parking Structure Extension below West Hollywood Park (Geotechnologies Inc, Appendix E). 3.7.1 Environmental Setting Surface Hydrology The City of West Hollywood discharges stormwater via regional underground storm drains into the upper reach of Ballona Creek, a subwatershed of Santa Monica Bay. The Ballona Creek Watershed is approximately 128 square miles in size and is bounded by the Santa Monica Mountains to the north and the Baldwin Hills to the south. The Santa Monica Bay monitoring site for West Hollywood and the other Ballona Creek cities discharging into Santa Monica Bay is at Dockweiler Beach, a site located over 10 miles downstream from the City of West Hollywood. Of the Ballona Creek watershed tributary to this site, 81% is under the jurisdiction of the City of Los Angeles. The other 19% of the watershed area is within the jurisdiction of the cities of Beverly Hills, Culver City, Inglewood, Santa Monica, and West Hollywood; the County of Los Angeles; and Caltrans (City of West Hollywood 2010). Existing stormwater runoff from the project site is conveyed via sheet flow and curb drains to the adjacent streets. -

Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Master Plan

Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Master Plan April 2005 Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Steering Committee Ann Dalkey and Travis Longcore, Co-Chairs Editor’s Note This document includes text prepared by several authors. Julie Stephenson and Dr. Antony Orme completed research and text on geomorphology (Appendix A). Dr. Ronald Davidson researched and reported South Bay history (Appendix B). Sarah Casia and Leann Ortmann completed biological fieldwork, supervised by Dr. Rudi Mattoni. All photographs © Travis Longcore. GreenInfo Network prepared maps under the direction of Aubrey Dugger (http://www.greeninfo.org). You may download a copy of this plan from: http://www.urbanwildlands.org/bbrp.html This plan was prepared with funding from California Proposition 12, administered by the California Coastal Conservancy and the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission through a grant to the Los Angeles Conservation Corps and The Urban Wildlands Group. Significant additional funding was provided by a grant from the City of Redondo Beach. Preferred Citation Longcore, T. (ed.). 2005. Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Master Plan. Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Steering Committee, Redondo Beach, California. 2 Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... iii Introduction .........................................................................................................................5 Goals.....................................................................................................................................6 -

Issue Bibliography

Issue Bibliography Abbott, C.C. Anderson, Eugene N., Jr. 1879 Artifact Descriptions. In, Report Upon 1964 A Bibliography of the Chumash and Their United States Geographical Surveys West of Predecessors. University of California the One Hundredth Meridian. 7(1):49-116, Archaeological Survey Annual Reports 61: 122-239 (Mortars and pestles are discussed 25-74. Berkeley. on pp. 70-92). U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington. Armstrong, Douglas V. 1985 Archaeology on San Clemente Island, Allen, Larry G. Summer 1985. Ms. on file, Natural Resources 1985 A Habitat Analysis of Nearshore Marine Office, Naval Air Station North Island, San Fisheries from Southern California. Bulletin Diego. of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 84(3):134-155. Los Angeles. Axford, L. Michael 1975 Archaeological Research on San Clemente Alliot, Hector Island, California (Research proposal 1915 Burial Methods of the Southern California submitted to Naval Undersea Center, San Islanders. Bulletin of the Southern California Diego, California). Ms. on file, Natural Academy of Sciences 14(2). Los Angeles. Resources Office, Naval Air Station North (Reprinted in Masterkey 43(4): 125-131. Island, San Diego. Southwest Museum, Los Angeles, 1969) 1976 Archaeological Research on San Clemente 1917 Prehistoric use of bitumen in Southern Island, Progress Report. Ms. on file, Natural California. Bulletin of the Southern Califor- Resources Office, Naval Air Station North nia Academy of Sciences 16(2). Los Angeles. Island, San Diego. 1969 (see 1915) 1977 Archaeological Research on San Clemente Island, Progress Report. Ms. on file, Natural Ames, Jack A. Resources Office, Naval Air Station North 1972 California Sheephead. Ms. On file, California Island, San Diego.