The Post-9/11 Global Framework for Cargo Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shipping and Port Security: Challenges and Legal Aspects

The Business and Management Review, Volume 10 Number 5 December 2019 Shipping and port security: Challenges and legal aspects Zillur Rahman Bhuiyan Managing Director, Marinecare Consultants Bangladesh Ltd. Marine Consultant in Maritime Safety and Security Key Words Globalization, ISPS Code, maritime transport system, security threats, UNCLOS. Abstract The current trend of globalization provides intense impact on access to resources, raw materials and markets, expedited by modern maritime transport system comprising shipping and port operations. Security of ships and port facilities, thus, discernibly an enormous challenge to the globalized world. The international maritime transport system is vulnerable to piracy, terrorism, illegal drug trafficking, gun-running, human smuggling, maritime theft, fraud, damage to ships & port facilities, illegal fishing and pollution, which can all disrupt maritime supply chains to the heavy cost of the global economy. This paper discusses the nature and effect of the security threats to the international shipping and port industry with impact on the international trade & commerce and governmental economy, taking into consideration of the emerging geopolitics, Sea Lines of Communication, chokepoints of maritime trading routes and autonomous ships. The existing legislative measures against maritime security appraised and evolution of automation and digitalization of shipping and port operations taken into consideration. Studying the contemporary maritime transport reviews, existing legislation and the threat scenarios to the shipping and port operations, this paper identifies further advancement to the existing maritime security legislation in respect of piracy and terrorism at sea, and recommends amendment to the International Ship and Port Security (ISPS) Code under the SOLAS Convention. 1 Introduction Globalization is based on the unrestricted movement of commodities, resources, information and people enhancing international trade and commerce through connectivity between the places of production and places of consumption. -

Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Followint

Working Paper Series This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/ Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Following September 11, 2001† Jeffrey M. Lacker* Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, 23219, USA December 23, 2003 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper 03-16 Abstract The monetary and payment system consequences of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are reviewed and compared to selected U.S. banking crises. Interbank payment disruptions appear to be the central feature of all the crises reviewed. For some the initial trigger is a credit shock, while for others the initial shock is technological and operational, as in September 11, but for both types the payments system effects are similar. For various reasons, interbank payment disruptions appear likely to recur. Federal Reserve credit extension following September 11 succeeded in massively increasing the supply of banks’ balances to satisfy the disruption-induced increase in demand and thereby ameliorate the effects of the shock. Relatively benign banking conditions helped make Fed credit policy manageable. An interbank payment disruption that coincided with less favorable banking conditions could be more difficult to manage, given current daylight credit policies. Keywords: central bank, Federal Reserve, monetary policy, discount window, payment system, September 11, banking crises, daylight credit. † Prepared for the Carnegie-Rochester Conference on Public Policy, November 21-22, 2003. Exceptional research assistance was provided by Hoossam Malek, Christian Pascasio, and Jeff Kelley. I have benefited from helpful conversations with Marvin Goodfriend, who suggested this topic, David Duttenhofer, Spence Hilton, Sandy Krieger, Helen Mucciolo, John Partlan, Larry Sweet, and Jack Walton, and helpful comments from Stacy Coleman, Connie Horsley, and Brian Madigan. -

REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS on U.S. FACILITIES in BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012

LLIGE - REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS ON U.S. FACILITIES IN BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012 together with ADDITIONAL VIEWS January 15, 2014 SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE United States Senate 113 th Congress SSCI Review of the Terrorist Attacks on U.S. Facilities in Benghazi, Libya, September 11-12, 2012 I. PURPOSE OF TIDS REPORT The purpose of this report is to review the September 11-12, 2012, terrorist attacks against two U.S. facilities in Benghazi, Libya. This review by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (hereinafter "SSCI" or "the Committee") focuses primarily on the analy~is by and actions of the Intelligence Community (IC) leading up to, during, and immediately following the attacks. The report also addresses, as appropriate, other issues about the attacks as they relate to the Department ofDefense (DoD) and Department of State (State or State Department). It is important to acknowledge at the outset that diplomacy and intelligence collection are inherently risky, and that all risk cannot be eliminated. Diplomatic and intelligence personnel work in high-risk locations all over the world to collect information necessary to prevent future attacks against the United States and our allies. Between 1998 (the year of the terrorist attacks against the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania) and 2012, 273 significant attacks were carried out against U.S. diplomatic facilities and personnel. 1 The need to place personnel in high-risk locations carries significant vulnerabilities for the United States. The Conimittee intends for this report to help increase security and reduce the risks to our personnel serving overseas and to better explain what happened before, during, and after the attacks. -

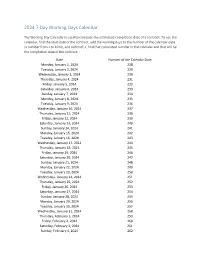

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, January 1, 2024 228 Tuesday, January 2, 2024 229 Wednesday, January 3, 2024 230 Thursday, January 4, 2024 231 Friday, January 5, 2024 232 Saturday, January 6, 2024 233 Sunday, January 7, 2024 234 Monday, January 8, 2024 235 Tuesday, January 9, 2024 236 Wednesday, January 10, 2024 237 Thursday, January 11, 2024 238 Friday, January 12, 2024 239 Saturday, January 13, 2024 240 Sunday, January 14, 2024 241 Monday, January 15, 2024 242 Tuesday, January 16, 2024 243 Wednesday, January 17, 2024 244 Thursday, January 18, 2024 245 Friday, January 19, 2024 246 Saturday, January 20, 2024 247 Sunday, January 21, 2024 248 Monday, January 22, 2024 249 Tuesday, January 23, 2024 250 Wednesday, January 24, 2024 251 Thursday, January 25, 2024 252 Friday, January 26, 2024 253 Saturday, January 27, 2024 254 Sunday, January 28, 2024 255 Monday, January 29, 2024 256 Tuesday, January 30, 2024 257 Wednesday, January 31, 2024 258 Thursday, February 1, 2024 259 Friday, February 2, 2024 260 Saturday, February 3, 2024 261 Sunday, February 4, 2024 262 Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, February 5, 2024 263 Tuesday, February 6, 2024 264 Wednesday, February -

Lessons Learned from 9/11: DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents

SEPTEMBER 2006 Lessons Learned From 9/11: DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents PRESIDENT’S DNA I N I T IA T I VE www.DNA.gov U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Alberto R. Gonzales Attorney General Regina B. Schofield Assistant Attorney General Glenn R. Schmitt Acting Director, National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs Partnerships for Safer Communities www.ojp.usdoj.gov Lessons Learned From 9/11: DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents SEPTEMBER 2006 National Institute of Justice This document is not intended to create, and may not be relied upon to create, any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any party in any matter civil or criminal. The opinions, factual and other findings, conclusions, or recommendations in this publication represent the points of view of a majority of the KADAP members and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. NCJ 214781 Preface n September 11, 2001, 2,792 people This report discusses the incorporation of DNA were killed in terrorist attacks on the identification into a mass fatality disaster plan, O World Trade Center (WTC) in New York including how to: City. The number of victims, the condition of their ■ Establish laboratory policies and procedures, remains, and the duration of the recovery effort including the creation of sample collection made the identification of the victims the most documents. difficult ever undertaken by the forensic commu nity in this country. ■ Assess the magnitude of an identification effort, and identify and acquire resources to In response to this need, the National Institute of respond. -

2021 Calendar Campaign

One Tail at a Time 2021 Calendar Pets Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Friday, January 1 Not Available Saturday, February 20 Not Available Sunday, April 11 Available Monday, May 31 Not Available Tuesday, July 20 Available Wednesday, September 8 Not Available Thursday, October 28 Available Thursday, December 16 Available Saturday, January 2 Available Sunday, February 21 Available Monday, April 12 Not Available Tuesday, June 1 Available Wednesday, July 21 Not Available Thursday, September 9 Available Friday, October 29 Available Friday, December 17 Available Sunday, January 3 Available Monday, February 22 Available Tuesday, April 13 Available Wednesday, June 2 Available Thursday, July 22 Not Available Friday, September 10 Not Available Saturday, October 30 Available Saturday, December 18 Not Available Monday, January 4 Not Available Tuesday, February 23 Available Wednesday, April 14 Available Thursday, June 3 Available Friday, July 23 Available Saturday, September 11 Available Sunday, October 31 Not Available Sunday, December 19 Available Tuesday, January 5 Available Wednesday, February 24 Available Thursday, April 15 Not Available Friday, June 4 Available Saturday, July 24 Available Sunday, September 12 Available Monday, November 1 Available Monday, December 20 Available Wednesday, January 6 Available Thursday, February 25 Available Friday, April 16 Not Available Saturday, June 5 Available Sunday, July 25 Available Monday, September 13 Available Tuesday, November 2 Available -

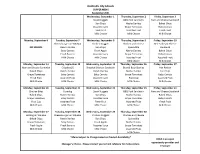

September 2021 Supper.Pdf

Huntsville City Schools SUPPER MENU September 2021 Wednesday, September 1 Thursday, September 2 Friday, September 3 Steak Nuggets BBQ Pork Sandwich Ham and Cheese Sandwich Sun Chips Nacho Doritos Baked Chips Assorted Juice Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Fresh Fruit Assorted Fruit Fresh Fruit Milk Choice Milk Choice Milk Choice Monday, September 6 Tuesday, September 7 Wednesday, September 8 Thursday, September 9 Friday, September 10 Cheeseburger on WG Bun Chicken Nuggets Chicken and Cheese Deli Turkey & Cheese NO SCHOOL Ranch Doritos Sun Chips Quesadilla Sandwich Baby Carrots Fresh Apple Nacho Doritos Baked Chips Fresh Banana Assorted Juice Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Milk Choice Milk Choice Assorted Fruit Assorted Fruit Milk Choice Milk Choice Monday, September 13 Tuesday, September 14 Wednesday, September 15 Thursday, September 16 Friday, September 17 Ham and Cheese Sandwich Crispitos(2) Breaded Chicken Sandwich Beef & Bean Burrito Hot Pocket Baked Chips Ranch Doritos Ranch Doritos Nacho Doritos Sun Chips Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Baby Carrots Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Fresh Fruit Assorted Fruit Assorted Juice Fruit Cup Assorted Fruit Milk Choice Milk Choice Milk Choice Milk Choice Milk Choice Monday, September 20 Tuesday, September 21 Wednesday, September 22 Thursday, September 23 Friday, September 24 Chicken Bites Corndog Steak Nuggets BBQ Pork Sandwich Ham and Cheese Sandwich Baked Chips Ranch Doritos Sun Chips Nacho Doritos Baked Chips Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Assorted Juice Grape Tomatoes Baby Carrots Fruit Cup Assorted Fruit -

Early Dance Division Calendar 17-18

Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 1 September 9 – November 3 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes September 11 Class September 12 Class September 18 Class September 19 Class September 25 Class September 26 Class October 2 Class October 3 Class October 9 Class October 10 Class October 16 Class October 17 Class October 23 Class October 24 Class October 30 Last Class October 31 Last Class Wednesday Classes Thursday Classes September 13 Class September 14 Class September 20 Class September 21* Class September 27 Class September 28 Class October 4 Class October 5 Class October 11 Class October 12 Class October 18 Class October 19 Class October 25 Class October 26 Class November 1 Last Class November 2 Last Class Saturday Classes Sunday Classes September 9 Class September 10 Class September 16 Class September 17 Class September 23 Class September 24 Class September 30* Class October 1 Class October 7 Class October 8 Class October 14 Class October 15 Class October 21 Class October 22 Class October 28 Last Class October 29 Last Class *Absences due to the holiday will be granted an additional make-up class. Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 2 November 4 – January 22 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes November 6 Class November 7 Class November 13 Class November 14 Class November 20 No Class November 21 No Class November 27 Class November 28 Class December 4 Class December 5 Class December 11 Class December 12 Class December 18 Class December 19 Class December 25 No Class December 26 No Class January 1 No Class January 2 No Class January 8 Class -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

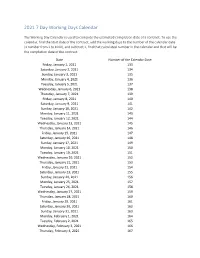

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

U.S. Coast Guard Port Security Unit History

U.S. Coast Guard Port Security Unit History Early Roots The roots of the Coast Guard's deployable port security mission are traced back to World War I and World War II and the traditional CONUS port safety and security duties of the Captain of the Port (COTP). During World War II, some overseas COTP-type operations were carried out by the Coast Guard in both the Pacific and European Theaters. Experiences in Vietnam demonstrated that a need for Coast Guard port security capabilities in overseas ports continued to exist. During the early 1980's, DoD planners formally identified the need for port security forces in OCONUS seaports of debarkation. Dialogue began between the Army, Navy, and Coast Guard, and the concept of the deployable Port Security Unit (PSU) was born. In January 1985 the Commandant approved three notional PSUs to respond to the requirements of DoD operations plans. The three units were located in the Ninth Coast Guard District at Buffalo, NY, Cleveland, OH, and Milwaukee, WI. Mission Defined PSUs are organized, equipped, and trained to operate in joint security areas, specifically in accessible (ice-free) harbors and port areas worldwide in support of regional Combatant Commanders’ requirements, and in company with DoD for national defense regional contingencies. PSUs provide 24-hour operations under all environmental conditions within the limits of equipment and personnel. PSUs normally protect vessels in transit, at the pier/port complex, or along the waterfront facility. Harbor defense and port security operations are frequently characterized by confined and traffic-congested water and air space. Notional Mission Assessment In the years between the approval of the three notional PSUs and their first deployment in 1990, the PSUs suffered from inconsistent budgetary, programmatic, and training support. -

Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities

Order Code RL33787 Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities Updated May 14, 2007 Paul W. Parfomak and John Frittelli Resources, Science, and Industry Division Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities Summary A key challenge for U.S. policy makers is prioritizing the nation’s maritime security activities among a virtually unlimited number of potential attack scenarios. While individual scenarios have distinct features, they may be characterized along five common dimensions: perpetrators, objectives, locations, targets, and tactics. In many cases, such scenarios have been identified as part of security preparedness exercises, security assessments, security grant administration, and policy debate. There are far more potential attack scenarios than likely ones, and far more than could be meaningfully addressed with limited counter-terrorism resources. There are a number of logical approaches to prioritizing maritime security activities. One approach is to emphasize diversity, devoting available counter- terrorism resources to a broadly representative sample of credible scenarios. Another approach is to focus counter-terrorism resources on only the scenarios of greatest concern based on overall risk, potential consequence, likelihood, or related metrics. U.S. maritime security agencies appear to have followed policies consistent with one or the other of these approaches in federally-supported port security exercises and grant programs. Legislators often appear to focus attention on a small number of potentially catastrophic scenarios. Clear perspectives on the nature and likelihood of specific types of maritime terrorist attacks are essential for prioritizing the nation’s maritime anti-terrorism activities. In practice, however, there has been considerable public debate about the likelihood of scenarios frequently given high priority by federal policy makers, such as nuclear or “dirty” bombs smuggled in shipping containers, liquefied natural gas (LNG) tanker attacks, and attacks on passenger ferries.