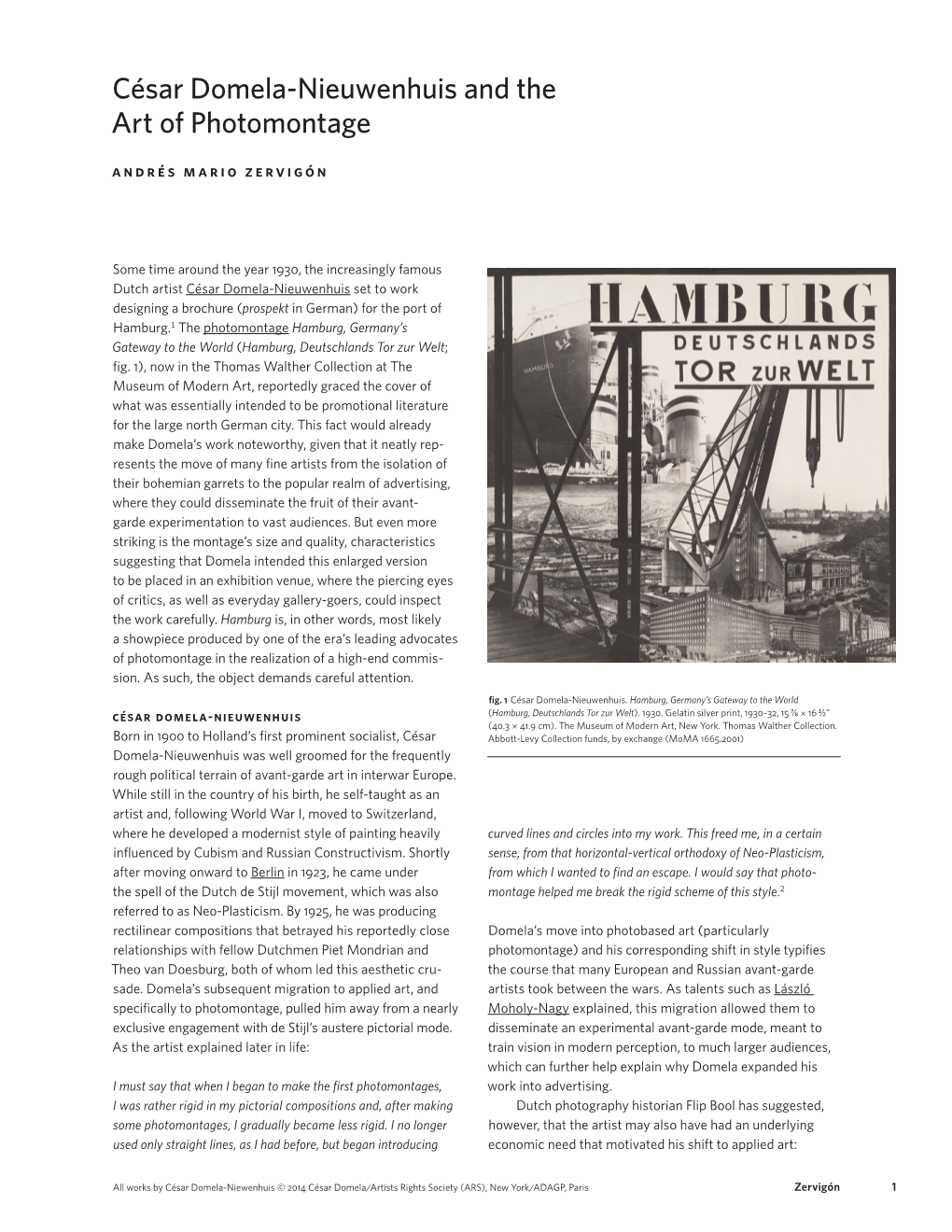

César Domela-Nieuwenhuis and the Art of Photomontage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Landscape Institute Technical Guidance Note Public ConsuDRAFTltation Draft 2018-06-01 To the recipient of this draft guidance The Landscape Institute is keen to hear the views of LI members and non-members alike. We are happy to receive your comments in any form (eg annotated PDF, email with paragraph references ) via email to [email protected] which will be forwarded to the Chair of the working group. Alternatively, members may make comments on Talking Landscape: Topic “Photography and Photomontage Update”. You may provide any comments you consider would be useful, but may wish to use the following as a guide. 1) Do you expect to be able to use this guidance? If not, why not? 2) Please identify anything you consider to be unclear, or needing further explanation or justification. 3) Please identify anything you disagree with and state why. 4) Could the information be better-organised? If so, how? 5) Are there any important points that should be added? 6) Is there anything in the guidance which is not required? 7) Is there any unnecessary duplication? 8) Any other suggeDRAFTstions? Responses to be returned by 29 June 2018. Incidentally, the ##’s are to aid a final check of cross-references before publication. Contents 1 Introduction Appendices 2 Background Methodology App 01 Site equipment 3 Photography App 02 Camera settings - equipment and approaches needed to capture App 03 Dealing with panoramas suitable images App 04 Technical methodology template -

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019 Jan Tschichold. Die Frau ohne Namen (The Woman Without a Name) poster, 1927. Printed by Gebrüder Obpacher AG, Munich. Photolithograph. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Peter Stone Poster Fund. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Jan Tschichold and the New February 14– Typography: Graphic Design July 7, 2019 Between the World Wars Jan Tschichold and the New Typography: Graphic Design Between the World Wars, a Bard Graduate Center Focus Project on view from February 14 through July 7, 2019, explores the influence of typographer and graphic designer Jan Tschichold (pronounced yahn chih-kold; 1902-1974), who was instrumental in defining “The New Typography,” the movement in Weimar Germany that aimed to make printed text and imagery more dynamic, more vital, and closer to the spirit of modern life. Curated by Paul Stirton, associate professor at Bard Graduate Center, the exhibition presents an overview of the most innovative graphic design from the 1920s to the early 1930s. El Lissitzky. Pro dva kvadrata (About Two Squares) by El Lissitzky, 1920. Printed by E. Haberland, Leipzig, and published by Skythen, Berlin, 1922. Letterpress. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, While writing the landmark book Die neue Typographie Jan Tschichold Collection, Gift of Philip Johnson. Digital Image © (1928), Tschichold, one of the movement’s leading The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. designers and theorists, contacted many of the fore- most practitioners of the New Typography throughout Europe and the Soviet Union and acquired a selection The New Typography is characterized by the adoption of of their finest designs. -

Tristan Tzara

DADA Dada and dadaism History of Dada, bibliography of dadaism, distribution of Dada documents International Dada Archive The gateway to the International Dada Archive of the University of Iowa Libraries. A great resource for information about artists and writers of the Dada movement DaDa Online A source for information about the art, literature and development of the European Dada movement Small Time Neumerz Dada Society in Chicago Mital-U Dada-Situationist, an independent record-label for individual music Tristan Tzara on Dadaism Excerpts from “Dada Manifesto” [1918] and “Lecture on Dada” [1922] Dadart The site provides information about history of Dada movement, artists, and an bibliography Cut and Paste The art of photomontages, including works by Heartfield, Höch, Hausmann and Schwitters John Heartfield The life and work of the photomontage artist Hannah Hoch A collection of photo montages created by Hannah Hoch Women Artists–Dada and Surrealism An excerpted chapter from Margaret Barlow’s illustrated book Women Artists Helios A beginner’s guide to Dada Merzheft German Dada, in German Dada and Surrealist Film A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library La Typographie Dada D.E.A. memoir in French by Breuil Eddie New York Avant-Garde, 1913-1929 New York Dada and the Armory Show including images and bibliography Excentriques A biography of Arthur Cravan in French Tristan Tzara, a Biography Excerpt from François Buot’s biography of Tzara,L’homme qui inventa la Révolution Dada Tristan Tzara A selection of links on Tzara, founder of the Dada movement Mina Loy’s lunar odyssey An online collection of Mina Loy’s life and work Erik Satie The homepage of Satie 391 Experimental art inspired by Picabia’s Dada periodical 391, with articles on Picabia, Duchamp, Ball and others Man Ray Internet site officially authorized by the Man Ray Trust to offer reproductions of the Man Ray artworks. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

'Netherlands Bauhaus – Pioneers of a New World

⏲ 05 February 2019, 11:42 (CET) ‘netherlands bauhaus – pioneers of a new world’ 9 February – 26 May 2019 Images and captions ‘netherlands bauhaus’, with over 800 Bauhaus objects, opens this weekend. It is the final major exhibition at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen before its renovation. On the opening day – Saturday, February 9 – admission to the museum is free for everyone. Prior to the large-scale renovation of the museum building in Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is staging one last major exhibition in the 1500-square-metre space of the Bodon Gallery. In 2019 it is the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus, the legendary art and design school that still has a palpable influence on contemporary design and architecture. ‘netherlands bauhaus – pioneers of a new world’ offers a unique insight into the inspiring interaction between the Netherlands and the Bauhaus. It lays bare the ‘netherlands bauhaus’ network in a large-scale survey, with over 800 objects and works of art. The exhibition is accompanied by a volume of 20 essays about the ‘netherlands bauhaus’ connections and an interactive digital tour. Bauhaus-related events are also being staged throughout Rotterdam. The exhibition will be opened by Said Kasmi, the City of Rotterdam’s Alderman for Culture, on the evening of Friday, 8 February. This is followed by Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s open day on Saturday, 9 February, when besides ‘netherlands bauhaus’, the exhibitions ‘When the Shutters Close: Highlights from the Collection’ and ‘Co Westerik: Everyday Wonder’ can be visited for free. Mienke Simon Thomas, Curator of Applied Art and Design: “This exhibition about the influence of the Bauhaus is a great fit with Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and with Rotterdam: it exudes ambition, underscores the importance of cooperation and is distinctly colourful.” The exhibition Through works of art, furniture, ceramics, textiles, photographs, typography and architecture, ‘netherlands bauhaus – pioneers of a new world’ reveals the influence of the Bauhaus in the Netherlands, and vice-versa. -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience Jennifer L. Lindsay Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2010 ©2010 Jennifer Laurel Lindsay All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.............................................................................................iii PREFACE........................................................................................................................... x ACKNOWLDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... xiv INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1. CRANBROOK: “[A] RESEARCH INSTITUTION OF CREATIVE ART”............................................................................................................ 11 Part 1. Founding the Cranbrook Academy of Art............................................................. 11 Section 1. Origins of the Academy....................................................................... 11 Section 2. A Curriculum for Modern Artists in Modern Times ........................... 16 Section 3. Cranbrook’s Landscape and Architecture: “A Total Work of Art”.... 20 Part 2. History of Weaving and Textiles at Cranbrook..................................................... 23 -

DIY-No3-Bookbinding-Spreads.Pdf

AN INTRODUCTION TO: BOOKBINDING CONTENTS Introduction 4 The art of bindery 4 A Brief History 5 Bookbinding roots 5 Power of the written word 6 Binding 101 8 Anatomy of the book 8 Binding systems 10 Paper selection 12 Handling paper 13 Types of paper 14 Folding techniques 14 Cover ideas 16 Planning Ahead 18 Choosing a bookbinding style for you 18 The Public is an activist design studio specializing in Worksheet: project management 20 changing the world. Step-by-step guide 22 This zine, a part of our Creative Resistance How-to Saddlestitch 22 Series, is designed to make our skill sets accessible Hardcover accordion fold 24 to the communities with whom we work. We Hardcover fanbook with stud 27 encourage you to copy, share, and adapt it to fit your needs as you change the world for the better, and to Additional folding techniques 30 share your work with us along the way. Last words 31 Special thanks to Mandy K Yu from the York-Sheridan Design Program in Toronto, for developing this zine What’s Out There 32 on behalf of The Public. Materials, tools, equipment 32 Printing services 32 For more information, please visit thepublicstudio.ca. Workshops 33 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this Selected Resources 34 license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. Online tutorials 34 Books & videos 34 About our internship program Introduction Bookbinding enhances the A brief history presentation of your creative project. You can use it to THE ART OF BINDERY BOOKBINDING ROOTS Today, bookbinding can assemble a professional portfolio, be used for: Bookbinding is a means for a collection of photographs or Long before ESS/ producing, sharing and circulating recipes, decorative guestbook, R the modern • portfolios • menus independent and community or volume of literature such as G-P Latin alphabet • photo albums • short stories • poetry books • much more work for artistic, personal or a personal journal or collection RINTIN was conceived, • journals commercial purposes. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Meerjarenbeleidsplan 2021-2024

Meerjarenbeleidsplan 2021-2024 Inhoudsopgave Hoofdstuk 1 7 Samenvatting Hoofdstuk 2 13 Meerjarenbeleidsplan 2021-2024 Hoofdstuk 3 89 Financiële gegevens: meerjarenbegroting 2021-2024 en balans 2017-2018 Hoofdstuk 4 97 Prestatiegegevens Hoofdstuk 5 101 Collectieplan Bijlagen > Rapportage Erfgoedhuis Zuid-Holland > Statuten > Wijziging statuten als gevolg van naamsverandering > Uittreksel Handelsregister Kamer van Koophandel Hoofdstuk 1 Samenvatting beleidsplan Naam instelling: Kunstmuseum Den Haag GEM | Museum voor Actuele Kunst Fotomuseum Den Haag Statutaire naam instelling: Stichting Kunstmuseum Den Haag Statutaire doelstelling: Het inrichten, in stand houden en exploiteren van de museumgebouwen en collecties die onder de naam “Kunstmuseum Den Haag” in eigendom toebehoren aan de gemeente Den Haag. Aard van de instelling: Museum Bezoekadres: Stadhouderslaan 41 Postcode en plaats: 2517 HV Den Haag Postadres: Postbus 72 Postcode en plaats: 2517 HV Den Haag Telefoonnummer: 070 3381 111 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kunstmuseum.nl Totalen 2017 2018 2019 2020 Tentoonstellingen (binnenland) 36 33 36 33 Bezoekersaantallen* 502.981 386.819 556.560 400.000 Totalen 2021 2022 2023 2024 Tentoonstellingen (binnenland) 36 30 30 30 Bezoekersaantallen* 400.000 400.000 400.000 400.000 * Bezoekersaantallen exclusief deelnemers basisonderwijs. Kunstmuseum Den Haag Dit museum doet iets met je. Het creëert afstand tot het alledaagse. Biedt troost. Zet je aan het denken. Laat je tot rust komen. Of juist niet. Met museumzalen in menselijke maat, komt Kunstmuseum Den Haag het liefst dichtbij. Zo dichtbij dat kunst intiem wordt. En je niets anders kan dan naar binnen kijken. 8 Kunstmuseum Den Haag vindt dat iedereen dicht bij kunst over wie we zijn. Er zijn maar weinig musea die doorlopend moet kunnen komen. -

Berlinische Galerie, Sprengel Museum Hannover and Bauhaus

P R E S S E M I T T E I L U N G 22. April 2016 B A U Berlinische Galerie, H A Sprengel Museum Hannover U S and Bauhaus Dessau Foundation D purchase the artistic estate E S of the photographer UMBO S A U Press conference: 09.05.2016, 12:30 in the Berlinische Galerie The work of Otto Maximilian Umbehr (1902-1980), nicknamed UMBO, will now be preserved as a complete portfolio. Thanks to the generous assistance of fourteen patrons and sponsors, the estate of this famous photographer of the modernist period has recently been acquired from three different provenances by the Berlinische Galerie, the Sprengel Museum Hannover and the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. The complex purchase deal was pushed forward with tirel- ess commitment by Galerie Kicken, Berlin, together with the artist's daugh- ter, Phyllis Umbehr, and her husband, Manfred Feith-Umbehr, as well as the German States Cultural Foundation (KSL). Generous assistance was given by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation, and the German Lottery Foundation Berlin, among others. UMBO, The Racing Reporter, UMBO, Grock, 12, from the UMBO, Dreamers, 1928/29, Egon Erwin Kisch (1885- series "Clown Grock", 1928- Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, 1948), 1926, Berlinische 1929, Sprengel Museum © Phyllis Umbehr/Galerie Galerie, © Phyllis Um- Hannover, © Phyllis Umbehr/ Kicken Berlin/ VG Bild-Kunst, behr/Galerie Kicken Berlin/ Galerie Kicken Berlin/VG Bonn, 2016 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2016 Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2016 UMBO's works are a substantial gain for the collections of the three muse- ums. -

Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016

Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016 PRESS KIT Hannah Höch, Untitled (From an Ethnographic Museum), 1929 © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2016 CONTENTS Press release Education programme and project space “Dada is here!” Press images Exhibition architecture Catalogue National and international loans Companion booklet including the exhibition texts New design for Museum Shop WWW.BERLINISCHEGALERIE.DE BERLINISCHE GALERIE LANDESMUSEUM FÜR MODERNE ALTE JAKOBSTRASSE 124-128 FON +49 (0) 30 –789 02–600 KUNST, FOTOGRAFIE UND ARCHITEKTUR 10969 BERLIN FAX +49 (0) 30 –789 02–700 STIFTUNG ÖFFENTLICHEN RECHTS POSTFACH 610355 – 10926 BERLIN [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Ulrike Andres Head of Marketing and Communications Tel. +49 (0)30 789 02-829 [email protected] Contact: ARTEFAKT Kulturkonzepte Stefan Hirtz Tel. +49 (0)30 440 10 686 [email protected] Berlin, 3 August 2016 Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016 Press conference: 03.08.2016, 11 am, opening: 04.08.2016, 7 pm Dada is 100 years old. The Dadaists and their artistic articulations were a significant influence on 20th-century art. Marking this centenary, the exhibition “Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other” is the first to explore Dadaist responses to non- European cultures and their art. It shows how frequently the Dadaists referenced non-Western forms of expression in order to strike out in new directions. The springboard for this centenary project was Dada’s very first exhibition at Han Coray’s gallery in Zurich. It was called “Dada. Cubistes. Art Nègre”, and back in Hannah Höch, Untitled (From an 1917 it displayed works of avant-garde and African art side by Ethnographic Museum), 1929 side.