California High-Speed Rail San Francisco to San Jose Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kathy Aoki Associate Professor of Studio Art Chair, Department of Art and Art History Santa Clara University, CA [email protected]

Kathy Aoki Associate Professor of Studio Art Chair, Department of Art and Art History Santa Clara University, CA [email protected] Education MFA ‘94, Printmaking. Washington University, School of Art, St. Louis, USA Recent Awards and Honors 2015 Prix-de-Print, juror Stephen Goddard, Art in Print, Nov-Dec 2015 issue. 2014 Turner Solo-Exhibition Award, juror Anne Collins Goodyear, Turner Print Museum, Chico, CA. 2013 Artist Residency, Frans Masereel Centrum, Kasterlee, Belgium Artist Residency, Fundaçion Valparaiso, Mojácar, Spain Palo Alto Art Center, Commission to create art installation with community involvement. (2012-2013) 2011-12 San Jose Museum of Art, Commission to make “Political Paper Dolls,” an interactive site-specific installation for the group exhibition “Renegade Humor.” 2008 Silicon Valley Arts Council Artist Grant. 2-d category. 2007 Artist’s Residency, Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France Strategic Planning Grant for pop-up book, Center for Cultural Innovation, CA. 2006 Djerassi Artist Residency, Woodside, CA 2004 Market Street Kiosk Poster Series, Public Art Award, SF Arts Commission Juror’s Award First Place, Paula Kirkeby juror, Pacific Prints 2004, Palo Alto, CA 2003 Artist Residency, Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, CA 2002 Trillium Fund, artist grant to work at Trillium Fine Art Press, Brisbane, CA 2001 Artist Residency. MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, NH Selected Permanent Collections: 2010 New York Metropolitan Museum of Art 2009 de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA. 2002 Harvard University Art Museums, Yale University Library 2000 Spencer Art Museum, University of Kansas 2001 Mills College Special Collections (Oakland, CA) and New York Public Library 1997, ‘99 Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Collection 1998 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Special Artist Book Collection 1995 Graphic Chemical and Ink, print purchase award, Villa Park, IL 1994 1998 Olin Rare Books, Washington University in St. -

Fletcher Benton

Fletcher Benton Born 1931 Jackson, Ohio. Currently lives and maintains a studio in San Francisco, CA. Education 1956 BFA, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio Awards and Honors 1979 Award for Distinguished Service to the Arts, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York 1980 President's Scholar Award, California State University, San Jose 1982 Award of Honor for Outstanding Achievement in Sculpture, San Francisco Arts Commission 1993 Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio 1994 Ohioana Career Award, Ohioana Library Association, Columbus Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Ohio 2008 Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture, International Sculpture Center 2012 Distinguished Arts Alumni Award, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio Teaching 1959 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland 1966-67 San Francisco Art Institute 1967-86 California State University, San Jose Selected Solo Exhibitions 1961 California Place of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco 1965 San Francisco Museum of Art 1967 Sonoma State College, Rohnert Park, California San Francisco Art Institute 1968 Humboldt State College, Arcata, California 1969 Milwaukee Art Center, Wisconsin 1970 San Francisco Museum of Art California State University, Ohico Berkeley Arts Center, Berkeley, California Reed College, Portland, Oregon Estudio Actual, Caracas, Venezuela 1971 Stanford University Museum of Art, California 1972 La Jolla Museum of Art, California 1973 Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona University of California, Davis AUSTIN ART PROJECTS -

Ethnic Communities of Santa Clara Valley 1848-1920

Smith-Layton Archive Ethnic Communities of Santa Clara Valley Charlene Duval, Executive Secretary [email protected] Leilani Marshall, Archivist 1848-1920 [email protected] Phone: 408-808-2064 by Ralph Pearce Sponsored by Linda L. Lester Your donations help us purchase historic photos. Thank you! © copyright 2018 Sourisseau Academy http://www.sourisseauacademy.org/ 1 Images on file at the Smith-Layton Archive, Sourisseau Academy for State and Local History February 2018 [18] The French. Thousands of French immigrants arrived in California during the Gold Rush, and many eventually settled in Santa Clara Valley. Names like Sainsevain, Lefranc, Masson and Mirassou are now synonymous with wine. Louis Pellier introduced the prune to the Valley, which became the nation’s leading producer of prunes. San Jose streets bear the names of Antoine Delmas and Edward and John Auzerais. The photograph on the left shows early French immigrant Pedro Sainsevain and his sons Carlos and Paul Sainsevain along with Carlos’ wife Lydia Higuera. Don Pedro reservoir is named for Pedro Sainsevain. The de Saisset family is pictured on the right. Pedro de Saisset was an early French resident and served as the honorary Vice-Consul for the French government. The De Saisset Museum memorializes Pedro’s son, artist Ernest de Saisset, shown in the photo waving his hat. The Alcantara Building/Metropole Hotel on South Market Street, built by the de Saisset heirs, is a San Jose Landmark. 2 Images on file at the Smith-Layton Archive, Sourisseau Academy for State and Local History February 2018 [19] Sourisseau Family. Felix Sourisseau was also an early French settler in San Jose. -

HHI Front Matter

A PUBLIC TRUST AT RISK: The Heritage Health Index Report on the State of America’s Collections HHIHeritage Health Index a partnership between Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services ©2005 Heritage Preservation, Inc. Heritage Preservation 1012 14th St. Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20005 202-233-0800 fax 202-233-0807 www.heritagepreservation.org [email protected] Heritage Preservation receives funding from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. However, the content and opinions included in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements . i Executive Summary . 1 1. Heritage Health Index Development . 3 2. Methodology . 11 3. Characteristics of Collecting Institutions in the United States. 23 4. Condition of Collections. 27 5. Collections Environment . 51 6. Collections Storage . 57 7. Emergency Plannning and Security . 61 8. Preservation Staffing and Activitives . 67 9. Preservation Expenditures and Funding . 73 10. Intellectual Control and Assessment . 79 Appendices: A. Institutional Advisory Committee Members . A1 B. Working Group Members . B1 C. Heritage Preservation Board Members. C1 D. Sources Consulted in Identifying the Heritage Health Index Study Population. D1 E. Heritage Health Index Participants. E1 F. Heritage Health Index Survey Instrument, Instructions, and Frequently Asked Questions . F1 G. Selected Bibliography of Sources Consulted in Planning the Heritage Health Index. G1 H. N Values for Data Shown in Report Figures . H1 The Heritage Health Index Report i Introduction and Acknowledgements At this time a year ago, staff members of thou- Mary Chute, Schroeder Cherry, Mary Estelle sands of museums, libraries, and archives nation- Kenelly, Joyce Ray, Mamie Bittner, Eileen wide were breathing a sigh of relief as they fin- Maxwell, Christine Henry, and Elizabeth Lyons. -

Kara Maria (Born: Binghamton, New York, 1968) Tel/Fax: 415-452-3089 • E-Mail: [email protected] • Website

SHARK’S INK. 550 BLUE MOUNTAIN ROAD LYONS CO 80540 303 823 9190 WWW.SHARKSINK.COM [email protected] Kara Maria (born: Binghamton, New York, 1968) tel/fax: 415-452-3089 • e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.karamaria.com Education 1998 MFA, Art Practice, University of California, Berkeley 1993 BA with honors, Art Practice, University of California, Berkeley Selected Solo and Two Person (*) Exhibitions 2012 • Kirk Hopper Fine Art, Amerwarpornica *, Dallas, TX 2011 • Virtuata, Cloud Nine, Milpitas, CA 2009 • b. sakata garo, Inviting the Storm, Sacramento, CA 2008 • Catharine Clark Gallery, Dystopia, San Francisco, CA 2007 • Nathan Larramendy Gallery, Paradise Lost, Ojai, CA 2006 • Arts Visalia, Zigzag, Visalia, CA 2005 • Smith Andersen Editions, Airborne, Palo Alto, CA 2004 • Miller/Block Gallery, Almost Paradise, Boston, MA 2002 • Catharine Clark Gallery, Fools Rush In, San Francisco, CA 2001 • Ampersand International Arts, Fabricator, San Francisco, CA • Babilonia 1808, Emerging Bay Area Artist Exhibition, Berkeley, CA • Catharine Clark Gallery, Plastic Picnic, San Francisco, CA 2000 • a.o.v., Plastic Dreams, San Francisco, CA 1999 • Cité Internationale des Arts, Doggie Doo Hop Scotch *, Paris, France 1998 • Patricia Sweetow Gallery, Introductions, San Francisco, CA Selected Group Exhibitions 2012 • Pratt Manhattan Gallery, Party Headquarters, New York, NY • Smith Andersen Editions, Gender Specific, Take it or Leave it, Palo Alto, CA • National Steinbeck Center, Banned & Recovered, Salinas, CA • SFMOMA Artists Gallery, Sin and -

Toward a Bay Area Science Learning Collaboratory

Toward a Bay Area Science Learning Collaboratory Leveraging San Francisco Bay Area Science-Technology Museums and Other Informal Science Education Programs as a Key Educational Resource for Student Learning and Teacher Professional Development Prepared for The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Menlo Park, CA By DesignWorlds for Learning, Inc. http://www.designworlds.com In Collaboration with ROCKMAN et cetera San Francisco, CA http://www.rockman-etc.org March 15, 2002 Toward a Bay Area Science Learning Collaboratory Leveraging San Francisco Bay Area Science-Technology Museums and Other Informal Science Education Programs as a Key Educational Resource for Student Learning and Teacher Professional Development Prepared for The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Menlo Park, CA By Ted M. Kahn, Ph.D. President and CEO DesignWorlds for Learning, Inc. http://www.designworlds.com In Collaboration with Saul Rockman Executive Director ROCKMAN et cetera San Francisco, CA http://www.rockman-etc.org March 15, 2002 ROCKMAN et cetera 49 Geary Street, #530 San Francisco CA 94108 Phone: 415/544-0788 http://www.rockman-etc.org Fax: 415/544-0789 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The research leading to this report was a result of some initial exploratory work done at the request of Dr. Ida Oberman, former Education Program Associate with the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (and now at Partners in School Innovation) and Dr. Marshall M. Smith, Education Program Director of the Hewlett Foundation in July- August 2001. The research summarized in this report was supported by Hewlett Foundation grant #2001-7331 to ROCKMAN et cetera, in collaboration with DesignWorlds for Learning, Inc. We would like to express our deep appreciation to Ida Oberman and to Mike Smith and Sally Tracy of the Hewlett Foundation for their interest and generous support of this work in support of education and lifelong learning. -

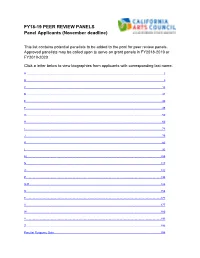

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Santa Clara University Santa Clara, California

Santa Clara University Santa Clara, California Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 23, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Purpose and Project Description II. Methodology III. Summary of Findings IV. Historic Context V. Regulatory Framework VI. Evaluation VII. Impacts and Mitigations VIII. References I. PURPOSE AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION David J. Powers & Associates has requested Carey & Co.’s assistance in evaluating three proposed projects at Santa Clara University which could affect buildings that are older than, or almost, 50 years of age. This report provides David J. Powers & Associates and the City Santa Clara with a description of the buildings within the vicinity of the project sites and those adjacent to the project sites, as well as evaluating each structure for potential historic resource status. Impacts and mitigation measures pertaining to the proposed projects potential effects on any historic resources are identified. Description of the Proposed Project Project 2 – Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Center The STEM Center would be comprised of three buildings to be constructed in three phases. Phase 1 will be located in the current location of Buildings 402 (Bannan Engineering Labs) and 403 (Murphy Hall). The existing buildings, both constructed in 1960, total 38,496 square feet. The new building on this site will be two attached structures totaling 157,900 square feet with a maximum height of four stories. Phase 2 will be located in the current location of Building 202 (Heafey Law Library). The existing building was originally constructed in 1962 and has had a number of additions over the Santa Clara University October 23, 2015 Historic Resource Resources Technical Report years. -

Faculty Resources Handbook 2004 the Edrp O Arrupe, S.J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Arrupe Resource Books Historical Documents 5-2004 Faculty Resources Handbook 2004 The edrP o Arrupe, S.J. Center for Community-Based Learning Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/arrupe_res_books . lI ThePe&0 Arrup,e, S.J. ' . ·Ceater forCom11tni~-Eased LearniDg·: Jatun!~ uwt~l~IDl~~®@~ · . I I , I SANTA C L ARA UNIVERSI T Y• 500 EL CAMINO REAL• SANTA CLARA, CA 95053 I :May,2004 i i <Toour <FacuftyCo((eagues, We at the )lrrupe Center are p(eased toprovide you with thisfacufty resource I fi.and6ook,oncommunity-6ased (earning.Ourwork,at the Center ca((son us tofaciCitate partnerships among awide variety-of groups - university administrators, community I partners, students, and you, the mem6ers ofthe SCV facufty. It is the professorwfi.o p(ays the essentia[, pivota( ro(e in any community-6ased [earning enterprise. 'Tfieprofessor integratesacademic contex; , community pCacements,cCassroom diafug, and rejfection. It is I our Ii.ope,and our mission,that this process wi(( fosterthe persona( transformation essentia( I to the Jesuit education of the wfi.o(eperson for others. <Tliismanua( was compi(etf6y <Bar6ara1(e([ey, a mem6er ofthe SCV Communications {f)epartment,wfi.o has worliga with us for many years.Sfi.e Ii.as proviaea scores of stuaents I witfi.weff-integratea community-6asea (earning, participatea in our2002 summerfacufty work§li.op,ana servea as our 2003-2004 )lrrupe Center <FacuftyScho(ar. 1(effey 's overview I of community-6asea (earning is atfi.orougfi. introauction to thisform of peaagogy,setting forth a cfear,accessi6[e contex; for the materiaCsthat fo(fuw: )lrrupe Center resources, samp{esy{(a6i, e:x:__empCary projects, stuaent rej(ections,ana more. -

Fletcher Benton

FLETCHER BENTON 1931 Born in Jackson, Ohio EDUCATION 1956 B.F.A., Miami University, Oxford, Ohio TEACHING 1959 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland 1966 – 1967 San Francisco Art Institute 1967 – 1986 California State University, San Jose SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 French Art Colony, Gallipolis, OH Lifetime Achievement Award, 4th Annual Palm Springs Fine Art Fair, Palm Springs, California Art, Design & Architecture Museum UC Santa Barbara 2013 de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, Sonoma, CA Lillian E. Jones Museum, Jackson, Ohio 2012 Modernism, San Francisco Naples Museum of Art, Naples, Florida 2011 Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden, Germany The Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin 2010 KANEKO – Open Space for Your Mind, Omaha, Nebraska Smith-Andersen Editions, Palo Alto, California Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, Sonoma, California Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada 2009 Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York 2008 SNZ Galerie, Wiesbaden, Germany Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden, Germany Jean Albano Art Gallery, Chicago Anne Reed Gallery, Ketchum, Idaho 2007 Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska 2006 Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden, Germany Palo Alto City Hall, California Riva Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, California 2005 Gallery Camino Real, Boca Raton, Florida Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood 2004 Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California Riva Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona 2003 Heidi Neuhoff Gallery, New York Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood 2002 Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, California San Antonio Museum of Art, Texas Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden, Germany 2002 2001 The Art Show, 7th Regiment Armory, New York Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, California Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood Galerie B. -

Profile Meeting with .City Representatives, Almost Full Time, Including Nights He Said

Spartan Daily Volume 75, Number 34 Serving the San Jose State Community Since 1934 Friday, October 1 7, 1980 Apathy blamed on midterms Dorm demonstration halted; march leader not surprised by Kathy Dutro mission to investigate the connection tee. A protest march designed to demonstrate dorm residents' The group has since decided to stop circulating the petition, Sherlock dissatisfaction with the mandatory $31.50 phone connection was cancelled said. He added that he will probably send it to the Public Utilities Com- due to student apathy, according to one of the organizers. mission anyway, with the approximately 500 signatures collected so far. The The march, which was planned for Wednesday, was scheduled to begin goal, according to Sherlock, was about 1,000 signatures. in front of West Hall and end at the Pacific Telephone offices at 190 N. Fifth He added that midterm pressure didn't allow him sufficient time to St. devote to signature gathering. According to Brad Sherlock, organizer of the march, the main stumbling The major effort of the residents' group has been devoted toward block, aside from student apathy, was the time of the year. working to switch the dorm phone system from the Centrex business system "Midterms really hurt," he said. to standard residential service. Such a change-over would reduce the con- A further obstacle developed when the rest of the group, working to nection fee from $31.50 to $16. change the dorm phone system, decided it would be better to work within the According to Steve Daniel, another member of the residents' group, system rather than challenge it, Sherlock said. -

RYAN CARRINGTON 341 Kenmore Avenue Sunnyvale, CA 94086 Phone: 608.279.4323 Email: [email protected] Website

RYAN CARRINGTON 341 Kenmore Avenue Sunnyvale, CA 94086 Phone: 608.279.4323 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ryancarringtonart.com Selected Solo Exhibits United We Stand, White Walls Gallery, San Francisco CA, 2015 Made In America, JCO’s Gallery, Los Gatos CA, 2015 American Ideals, Gavilan College Art Gallery, Gilroy CA 2013 Gravity LTD, New Coast Studios, Palo Alto CA 2013 Social Observations, Mohr Gallery, Mountain View CA 2012 Workmen’s Warehouse, San Jose State University, San Jose CA, 2011 American Gothic, San Jose State University, San Jose CA, 2010 White-Collar Pop, San Jose State University, San Jose CA, 2010 ¡Sí Se Puede!, San Jose State University, San Jose CA, 2009 Heat Drawing Series Exhibition, Artisan Gallery, Snowmass Village CO, 2007 Flood and Flora, Seventh-Floor Gallery, Madison WI, 2004 Selected Group Exhibits 2015 Good Tidings, JCO’s Gallery, Los Gatos CA Emerging Artists of the Bay Area Exhibition, Marin Museum of Contemporary Art, Novato CA Night at the Triton, Triton Museum of Art, Santa Clara CA 2014 Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series, Betti Ono Gallery, Oakland CA Alteration of the Grain, Evergreen Valley College, San Jose CA Contemporary Trompe L’oeil, John F. Peto Museum, Island Heights NJ Material Matters, Union Street Gallery, Chicago Heights IL Santa Clara University Faculty Show, Art Department Gallery, Santa Clara CA Art Party 2014, Fundraiser for the Silicon Valley Arts Council, San Jose CA Repetitive Stress, Art Ark Gallery, San Jose CA Soapbox, Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley CA 2014 Collector’s Choice