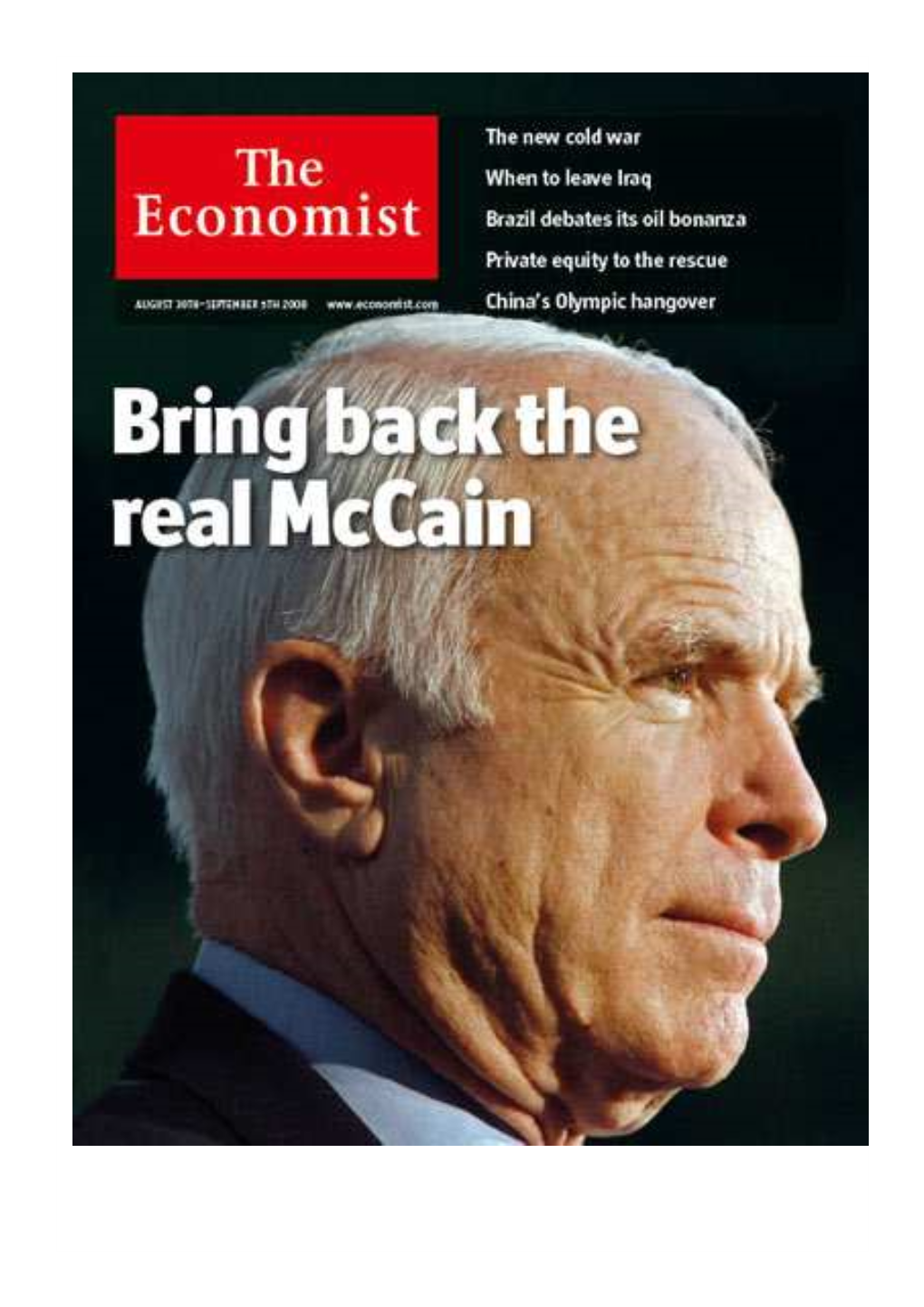

The Economist August 30 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperiale Konzert- Und Opernreisen

IMPERIALE KONZERT- UND OPERNREISEN September bis Dezember 2017 SEPTEMBER - HÖHEPUNKTE In der Staatsoper kann neben Aufführungen wie „Die Hochzeit des Figaro“, „Der Barbier von Sevilla“, „La Bohème“ u. a., sicherlich „Der Troubadour“ mit Anna Netrebko als Höhepunkt im September gesehen werden. Zusätzlich wird noch Mussorgski‘s „Chowanschtschina“ mit Ferruccio Furlanetto in der Titelrolle gegeben: „Eine zeitlose Parabel auf den ewigen Kreislauf von Machterwerb,- u. Verlust Einzelner auf Kosten des einfachen Volkes.“ Die Wiener Symphoniker treten sowohl im Musikverein, als auch im Konzerthaus auf mit Werken von Strauss und Dvorak. Die Wiener Philharmoniker geben ein Konzert im Musikverein mit Stardirigent Zubin Mehta. REISE 1: 4. bis 7. September 2017 EZ € 2.085,- | DZ € 1.580,- p. P. Montag, den 4.9. In der Staatsoper: Der Troubadour v. G. Verdi Mit George Petean, Anna Netrebko, Luciana D‘Intino, Marcelo Alvarez, Jongmin Park Dienstag, den 5.9. In der Staatsoper: Die Hochzeit des Figaro Mit Adam Plachetka, Dorothea Röschmann, Andrea Caroll, Carlos Alvarez, Margarita Gritskova Mittwoch, den 6.9. In der Staatsoper: Der Barbier von Sevilla v. G. Rossini Mit Ioan Hotea, Paolo Rumetz, Rachel Frankel, Marco Caria, Sorin Coliban REISE 2: 7. bis 10. September 2017 EZ € 2.065,- | DZ € 1.560,- p. P. Donnerstag, den 7.9. In der Staatsoper: Der Troubadour v. G. Verdi Mit George Petean, Anna Netrebko, Luciana D‘Intino, Marcelo Alvarez, Jongmin Park Freitag, den 8.9. In der Staatsoper: Chowanschtschina v. M. Mussorgski Mit Ferruccio Furlanetto, Christopher Ventris, Herbert Lippert, Andrzej Dobber, Ain Anger, Elena Maximova Samstag, den 9.9. In der Staatsoper: Die Hochzeit des Figaro Mit Adam Plachetka, Dorothea Röschmann, Andrea Caroll, Carlos Alvarez, Margarita Gritskova REISE 3: 8. -

Our Gender-Pay-Gap Report

Gender pay gap report 2020 Gender pay gap report 2020 Foreword The Economist Group is committed to being an organisation that promotes belonging and aims to have a Group culture that reflects inclusivity, diversity, and excellence. In our fourth year of reporting, the UK data shows a great improvement at the mean and, more importantly, at the median, where our gender pay gap has improved by one-third this year. The analysis indicates that changes in practices and policies, as described at the end of the report, have resulted in the improvement in the numbers. We have consistently reduced the fixed pay gap over the last three years with major improvements in the proportion of women recruited in higher paid roles (see page 6). However, we are far from parity and men still dominate the top quartile for pay despite the Group employing similar numbers of women and men. We are pleased to be making progress, and we are committed to the critical work ahead. We recognise the gender pay gap is still significant, and we are working to change it. Lara Boro Chief Executive March 2021 2 Gender pay gap report 2020 1. The UK gender pay gap (as per UK Government reporting guidelines) On the snapshot date of 5th April 2020, the Group employed 751 people in the UK (364 women and 387 men), mainly in London and Birmingham including editorial colleagues, marketing, research, sales, technology, consultancy, head office and support functions. Gender pay gap Women’s hourly pay rate* vs men’s Our gender pay gap has improved by one-third this year. -

Annual Report 2020

In pursuit of progress since Annual report 2020 report Annual Annual report 2020 In pursuit of progress since Annual report 2020 report Annual Annual report 2020 CONTENTS ANNUAL REPORT STRATEGIC REPORT 2 Five-year summary 3 Group overview 4 From the chairman 6 From the chief executive 8 From the editor 9 Business review: the year in detail 13 The Economist Educational Foundation 15 The Economist Group and environmental sustainability 17 Corporate governance: the Wates Principles, our Section 172(1) statement and our guiding principles REPORT AND ACCOUNTS GOVERNANCE 22 Directors 23 Executive team 24 Trustees, board committees 25 Directors’ report 28 Directors’ report on remuneration 31 Financial review CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 35 Independent auditor’s report to the members of The Economist Newspaper Limited 38 Consolidated income statement 39 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 40 Consolidated balance sheet 41 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 42 Consolidated cashflow statement 44 Notes to the consolidated financial statements COMPANY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 94 Company balance sheet 95 Company statement of changes in equity 96 Notes to the company financial statements NOTICES 108 Notice of annual general meeting 1 STRATEGIC REPORT Five-year summary 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 £m £m £m £m £m Income statement—continuing business* Revenue 326 333 329 303 282 Operating profit 31 31 38 43 47 Profit after taxation 21 25 28 39 37 Profit on sale of CQ-Roll Call, Inc - 43 - - - Profit on sale of Economist Complex - - - - -

POLAND Culture Andart

POLAND Culture and Art ISBN 978-83-8010-013-8 www.poland.travel EN Culture and Art 3 Culture and Art Culture and Art 5 Culture: Our national heritage and the testimony of romantic reflections Polish culture is woven from the memories of past greatness and the dreams of a better future, and its national character is deeply rooted in Romanticism. In every branch of contemporary art, our rich Polish folklore becomes a source of inspiration for artists. nown for being very musical, Poles love dance and music. Folk melodies Kcan be heard in Chopin’s works, while Krzysztof Penderecki and Witold Lutosławski set new standards in the world of avant-garde music. Poland attracts a lot of attention, thanks to its talented jazz musicians and young artists excelling in the domain of alternative music. The poetry of Wisława Szymborska, recognised with a Nobel Prize, is appreciated in many corners of the world. Like Szymborska’s poems, many others’ works have been translated into foreign languages: the literary reportages of Ryszard Kapuściński, the futuristic prose of Stanisław Lem or the dramas of Sławomir Mrożek. Igor Mitoraj and Magdalena Abakanowicz are consid- ered ambassadors of Polish sculpture, with their monumental works arousing worldwide admi- ration. Roman Opałka’s and Wilhelm Sasnal’s paintings are highly sought after by art collec- tors. ▶ ▶ Poland has been home to many illustrious personalities, whose work changed the face of the world. Some were scientists, like Nicolaus Coperni- cus or Marie Skłodowska-Curie. Others shaped our reality in different ways, for example, the founders of Hollywood, Samuel Goldwyn and the Warner brothers. -

Berlin and Beyond Berlin, Dresden & Leipzig

BERLIN AND BEYOND BERLIN, DRESDEN & LEIPZIG MAY 2-15, 2019 TOUR LEADER: CHRISTOPHER MENZ BERLIN AND BEYOND Overview BERLIN, DRESDEN & LEIPZIG Berlin is one of the most interesting and diverse of all the great capitals of Europe, and is currently enjoying a major cultural renaissance. First Tour dates: May 2-15, 2019 documented in the 13th century, the city has been the capital of the Prussian Empire, the German Empire, the Weimar Republic and the Third Tour leader: Christopher Menz Reich. Since 1989 the city has relished its role as the capital of a unified and re-energised Germany. Tour Price: $7,250 per person, twin share Berlin is home to some internationally renowned cultural institutions – Single Supplement: $1,750 for sole use of such as museums of antiquities and fine arts – and has ongoing double room significance as a centre of contemporary art and design. Berlin is also famous for its musical heritage, with outstanding ensembles such as the Booking deposit: $500 per person Berlin Philharmonic and three major opera houses adding great lustre to the city’s cultural landscape. Recommended airline: Qatar Airways or Singapore Airlines/Lufthansa This 14-day tour allows you to take an in-depth look at Berlin, and the nearby cities of Potsdam, Leipzig and Dresden. Daily walking tours, Maximum places: 20 background talks and guided visits trace the history and development of Berlin from its earliest days through the glory days of the Prussian and Itinerary: Berlin (5 nights), Leipzig (2 nights), German Empires to the darker days of the early 20th century and its Dresden (2 nights), Berlin (4 nights) rebirth after 1989. -

Integrated Licensing Agreement

TERMS AND CONDITIONS: INTEGRATED LICENSING AGREEMENT These Terms and Conditions form part of the Agreement between The Economist Group and Client and refer to words defined in the Integrated Licensing Agreement (or any agreement in which these terms are incorporated by reference). 1. Payment Terms All fees expressed herein are exclusive of sales tax, value added tax, or any other taxes and duties which, if applicable, will be charged to Client in addition to the fees. In addition to the fees, Client will be responsible for the payment of any withholding taxes that may be payable. Travel expenses are not included in the fee(s) and, if such charges are incurred, they will also be charged to Client in addition to the fees. All fees are non- refundable (except as otherwise specified herein) and are due within net 30 days of the invoice date. Payments made after the due date may be (in The Economist Group’s discretion) subject to a late fee equal to the lesser of 1.5% per month or the maximum allowed by law. 2. Licence of Trademarks 2.1 Where The Economist Group gives approval in writing in advance, The Economist Group grants to Client a non-exclusive, non-sub-licensable licence (during the term of this Agreement) to use the “Economist Intelligence Unit”, “Economist Events”, “Economist Films” or “(E) BrandConnect” (as applicable) name and/or logo, for the purpose only of: (i) promoting and marketing the Event(s), or (ii) attributing the Deliverables to Economist Films, Economist Events, EIU or (E) BrandConnect (as applicable) in accordance with this Agreement, PROVIDED THAT in each case (a) these trademarks will only be used in the exact format and specification as directed from time to time by The Economist Group, (b) all advertising, promotional, marketing and other material which feature the trademarks (in any medium or media) will be subject to the prior review by and written approval of The Economist Group before their publication or use, and (c) Client will not modify, amend or add to the content or format of any of the licensed trademarks in any manner. -

Register of Lords' Interests

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, National Library of Wales (interest ceased 31 March 2021) Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, Stephen Dodgson Trust (promotes continued awareness/performance of works of composer Stephen Dodgson) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Sesquicentenary Committee (music) Director, UK Focused Ultrasound Foundation (charitable company limited by guarantee) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director and Trustee, The Atlas Foundation (registered charity; seeks to improve lives of disadvantaged people across the world) Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) President (formerly Vice President), British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club (interest ceased 30 November 2020) ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the member is or will be paid to this company; see category 4(a)) Director, Visionable -

Press Release

The Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square London E14 4QW Telephone 020 7576 8000 Fax 020 7576 8500 www.eiu.com Press release Press enquiries Joanne McKenna: +44 (0)20 7576 8188 or [email protected] For immediate release: Asking better questions of data boosts performance, says Economist Intelligence Unit report An ability to ask better questions of data is central to driving better business outcomes, according to In search of insight and foresight: Getting more out of big data, an Economist Intelligence Unit report, sponsored by Oracle and Intel. According to a global EIU survey for this report, the vast majority of executives agree that asking better questions of data has already improved their organisation’s performance and will continue to lift it in the coming years. Nevertheless, many companies struggle to use data to gain insight into their business—and foresight into how best to move it forward. Lessons from successful firms reveal that achieving insight and foresight requires crafting savvy questions that test smart hypotheses, both of which are best fostered by open corporate cultures that prize data and its exploration. Other key findings include: • Focusing on a business outcome is crucial, yet a struggle for most companies. Defining, agreeing on and gearing data analyses towards clear, specific and relevant business objectives is difficult for many companies and a critical obstacle to translating data into insights, results and competitive advantage. Executives overwhelmingly consider predictions (70%) the most critical type of data insight for C-level decisions, followed by insights into trends (43%). • The main challenges are people-related. -

Democracy Index 2020 in Sickness and in Health?

Democracy Index 2020 In sickness and in health? A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com The world leader in global business intelligence The Economist Intelligence Unit (The EIU) is the research and analysis division of The Economist Group, the sister company to The Economist newspaper. Created in 1946, we have over 70 years’ experience in helping businesses, financial firms and governments to understand how the world is changing and how that creates opportunities to be seized and risks to be managed. Given that many of the issues facing the world have an international (if not global) dimension, The EIU is ideally positioned to be commentator, interpreter and forecaster on the phenomenon of globalisation as it gathers pace and impact. EIU subscription services The world’s leading organisations rely on our subscription services for data, analysis and forecasts to keep them informed about what is happening around the world. We specialise in: • Country Analysis: Access to regular, detailed country-specific economic and political forecasts, as well as assessments of the business and regulatory environments in different markets. • Risk Analysis: Our risk services identify actual and potential threats around the world and help our clients understand the implications for their organisations. • Industry Analysis: Five year forecasts, analysis of key themes and news analysis for six key industries in 60 major economies. These forecasts are based on the latest data and in-depth analysis of industry trends. EIU Consulting EIU Consulting is a bespoke service designed to provide solutions specific to our customers’ needs. We specialise in these key sectors: • Healthcare: Together with our two specialised consultancies, Bazian and Clearstate, The EIU helps healthcare organisations build and maintain successful and sustainable businesses across the healthcare ecosystem. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the European Country of Origin Information Network website. Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links • Advanced search help 13 May 2020 COL200220.E Colombia: The socio-economic situation, including demographics, employment rates, and economic sectors, particularly in Barranquilla, Bucaramanga and Ibagué (2017- May 2020) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 1. National Overview According to sources, the National Administrative Department of Statistics (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, DANE) reported, after conducting the 2018 census, that the population of Colombia was 45.5 million (Vellejo Zamudio 2 July 2019, 11; EIU 15 Nov. 2018). The same sources state that the results of the 2018 census, the first since 2005, were criticized due to the discrepancy between DANE's population projection and the census, with the projection calculating a population of 50 million (Vellejo Zamudio 2 July 2019, 11; EIU 15 Nov. 2018). According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) [1], DANE stated that the discrepancy stems from inaccuracy in the population projection and not the census (EIU 15 Nov. 2018). The 2019 Economic Survey of Colombia by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that Colombia had a population of 48.3 million in 2018 (OECD Oct. -

Spring 2015 CUES Internet at the Speed of Whoa

OPERAVolume 55 Number 05 | Spring 2015 CUES Internet at the speed of whoa. XFINITY® Internet delivers the fastest and most reliable in-home WiFi for all rooms, all devices, all the time. To learn more call 866-620-9714 or visit comcast.com Restrictions apply. Not available in all areas. Features and programming vary depending on area and level of service. WiFi claims based on April and October 2013 study by Allion Test Labs, Inc. Actual speeds vary and are not guaranteed. Reliably fast speed based on February 2013 FCC Broadband Report. Call for restrictions and complete details. ©2014 Comcast. All rights reserved. All trademarks are property of their respective owners. DIE WALKÜRE APRIL 18, 22, 25, 30 MAY 3 SWEENEY TODD APRIL 24, 26, 29 MAY 2, 8, 9 PATRICK SUMMERS PERRYN LEECH ARTISTIC & MUSIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR Margaret Alkek Williams Chair ADVERTISE IN OPERA CUES Opera Cues is published by Houston Grand Opera Association; all rights reserved. Opera Cues is produced by Houston Grand Opera’s Communications Department, Judith Kurnick, director. Director of Publications Laura Chandler Art Direction / Production Pattima Singhalaka Contributors Kim Anderson Paul Hopper Perryn Leech Elizabeth Lyons Patrick Summers For information on all Houston Grand Opera productions and events, or for a complimentary season brochure, please call the Customer Care Center at 713-228-OPERA (6737). Houston Grand Opera is a member of OPERA America, Inc., and the Theater District Association, Inc. Find HGO online: HGO.org facebook.com / houstongrandopera twitter.com / hougrandopera instagram.com/hougrandopera Readers of Houston Grand Opera’s Opera Cues magazine are the Mobile: HGO.org most desirable prospects for an advertiser’s message. -

CD-Liste Cda1209 11.11.12

1982 1973 mp3- mp3- CD 2 DVD CD CD 3 CD CD CD CD 2 CD CD CD CD CD CD 1973,01 5311,01 1975,01 1982,01 11.11.12 Rene Jacobs, Rachel Yakar, James Bowman, Ulrik Cold, Rita Dams, Jill Max vanGomez, Egmond, , Stiefermann,Chung,Kay Locky Johanna Stojkjovic, Siri Karoline Thornhill, Ann ,Hallenberg, , , Antonietta Cesare Stella, Valletti, Giuseppe Taddei, Barbieri, Fedora Renato Capecchi, , Rina Corsi, Giuseppe Modesti, Dilcheva,Kremena Johnny Maldonado, MariaDoerthe Sandmann, Allen, Tom Egbert Junghanns, Johnny Maldonado, Matthias , Vieweg, Sir White,Willard Measha Blue, ,Brueggergosman, Angel Haskin,Howard , Rodney Clarke, John Fulton, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , Anna Caterina Antonacci, Eva Maria Fabio Westbroek, Bryan Hymel, Capitanucci, Hanna Hipp, Barbara Senator, Brindley Sherratt, Ashley Holland, Michael , , Volle, , , , , , Soyer, ChristianeSoyer, Eda Robert Pierre, Robert Massard,Lloyd, , Jane Berbie, Dietrich Henschel, Pasichnyk,Olga Attila Jun, Dusseljee, Kor-Jan Tonbandstimme, Bonita Hyman, Christiane Mirka Oertel, Wagner, Marjana EmilLipovsek, Ivanov, Philippe Rouillon, Raimondi, Ildiko Jacob Wojciech Will, Drabowicz, Migliorini,Thierry Hans Peter Kammerer, Dobber,Andrzej Veronika Dzhieova, Rafal Siwek, Cristina Damian, Tigran Martirossian, , Nurgeldiyev, Dovlet Sergiu Saplacan, Kinga Dobay, Rebecca Rasmussen, MarkusThomas Volle, Pettersson, Christian Oldenburg, Ludvig Lindström, Nyqvist, Peter Christina Nicolai Gedda, Jules Bastin, Roger -- -- -- -- -- -- -- Nilsson, -- -- -- -- -- -- -- cda1209 Antonio Pappano Marc Soustrot