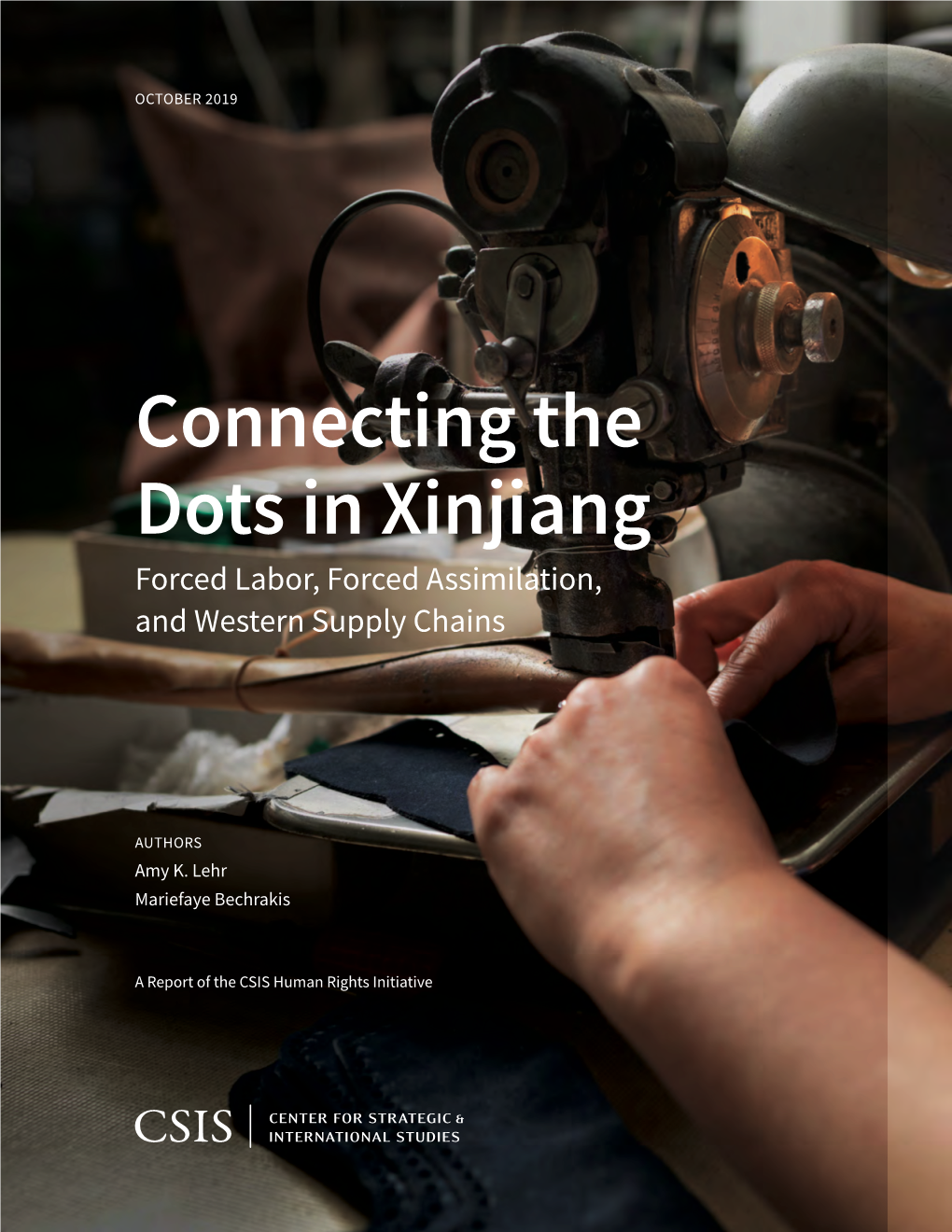

Connecting the Dots in Xinjiang Forced Labor, Forced Assimilation, and Western Supply Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reimagining Chinese Indonesians in Democratic Indonesia

Asia Pacific Bulletin Number 109 | May 10, 2011 Reimagining Chinese Indonesians in Democratic Indonesia BY RAY HERVANDI Indonesia’s initiation of democratic reforms in May 1998 did not portend well for Chinese Indonesians. Constituting less than 5 percent of Indonesia’s 240 million people and concentrated in urban areas, Chinese Indonesians were, at that point, still reeling from the anti-Chinese riots that had occurred just before Suharto’s fall. Scarred by years of discrimination and forced assimilation under Suharto, many Chinese Indonesians were uncertain—once again—about what the “new” Indonesia had in store for them. Yet, the transition to an open Indonesia has also resulted in greater space to be Chinese Indonesian. Laws and regulations discriminating against Chinese Indonesians have been Ray Hervandi, Project Assistant at repealed. Chinese culture has grown visible in Indonesia. Mandarin Chinese, rarely the the East-West Center in language of this minority in the past, evolved into a novel emblem of Chinese Washington, argues that Indonesians’ public identity. Indonesians need to “restart a civil Notwithstanding the considerably expanded tolerance post-Suharto Indonesia has conversation that examines how shown Chinese Indonesians, their delicate integration into Indonesian society is a work [Chinese Indonesians fit] in in progress. Failure to foster full integration would condemn Chinese Indonesians to a continued precarious existence in Indonesia and leave them vulnerable to violence at the Indonesia’s ongoing state- and next treacherous turning point in Indonesian politics. This undermines Indonesia’s nation-building project. In the ideals that celebrate the ethnic, religious, and cultural pluralism of all its citizens. -

"Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude"

By Adrian Zenz - Version of this paper accepted for publication by the journal Central Asian Survey "Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude" - China's Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang1 Adrian Zenz European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal Updated September 6, 2018 This is the accepted version of the article published by Central Asian Survey at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02634937.2018.1507997 Abstract Since spring 2017, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China has witnessed the emergence of an unprecedented reeducation campaign. According to media and informant reports, untold thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslims have been and are being detained in clandestine political re-education facilities, with major implications for society, local economies and ethnic relations. Considering that the Chinese state is currently denying the very existence of these facilities, this paper investigates publicly available evidence from official sources, including government websites, media reports and other Chinese internet sources. First, it briefly charts the history and present context of political re-education. Second, it looks at the recent evolution of re-education in Xinjiang in the context of ‘de-extremification’ work. Finally, it evaluates detailed empirical evidence pertaining to the present re-education drive. With Xinjiang as the ‘core hub’ of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing appears determined to pursue a definitive solution to the Uyghur question. Since summer 2017, troubling reports emerged about large-scale internments of Muslims (Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz) in China's northwest Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). By the end of the year, reports emerged that some ethnic minority townships had detained up to 10 percent of the entire population, and that in the Uyghur-dominated Kashgar Prefecture alone, numbers of interned persons had reached 120,000 (The Guardian, January 25, 2018). -

World Bank Document

24599 Volume 2 Public Disclosure Authorized China Integrated Pastoral Development Project Social Assessment Report Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region Public Disclosure Authorized "DRFT) Public Disclosure Authorized China Cross-cultural Consulting Center at Zhongshan University Guangzhou, Guangdong Public Disclosure Authorized People's Republic of China April 2002 CONTENTS Introduction: The Project and the Project Goals Chapter 1 The Social Assessment Work Selection of the Project SA Counties The SA Methodologies Chapter 2 Analysis of the SA Results The Basic conditions of The Project Area Demographic Data and Economy Data of the Project SA Counties Animal Husbandry of the Project SA Counties Pattems of Animal Husbandry in Xinjiang The Use of Land Other Natural Resources The Markets of Animal Husbandry Products The Labor Forces and Labor Division The Income Distribution Income and Taxation and Other Fees of the Households of the Project SA Counties The Production Organizations and Social Organizations of the Project SA Counties The Social Status and Labor Division of Women The Impact of the Local Customs on the Improvement of Animal Quality The Education and Information Transmission Chapter 3 The Environment and the Eco-environmental Restrains on The Project Chapter 4 The Demands of the Farmers and Herders in Project SA counties for the Project Loans and The Possibility of Loan Return Chapter 5 SA Team's Suggestions on the Project Appendix: Acknowledgment: Introduction: The Project and The Project Objectives China Xinjiang-Integrated Pastoral Development Project (CXISPP) Designed and implemented by the World Bank aims at, while maintaining and promoting the sustainable utility of the natural resources, enhancing the competitive ability of the animal husbandry products (wool and meat products) in the markets, improving the production and management system of animal production and raising the life level of those farmers and herders of the Xinjiang Project Areas. -

Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism

Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook China’s ‘War on Terror’ in Xinjiang: Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism Michael Clarke Regional Outlook i China’s ‘War on Terror’ in Xinjiang About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute produces innovative, interdisciplinary research on key developments in the politics, economics, societies and cultures of Asia and the South Pacific. By promoting knowledge of Australia’s changing region and its importance to our future, the Griffith Asia Institute seeks to inform and foster academic scholarship, public awareness and considered and responsive policy making. The Institute’s work builds on a 32 year Griffith University tradition of providing cutting- edge research on issues of contemporary significance in the region. Griffith was the first University in the country to offer Asian Studies to undergraduate students and remains a pioneer in this field. This strong history means that today’s Institute can draw on the expertise of some 50 Asia-Pacific focused academics from many disciplines across the university. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Regional Outlook’ papers publish the institute’s cutting edge, policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute ‘China’s “War on Terror” in Xinjiang: Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism’, Regional Outlook Paper No. 11, 2007. About the Author Michael Clarke Michael Clarke recently received his doctorate from Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia. His dissertation entitled ‘In the Eye of Power: China and Xinjiang from the Qing Conquest to the ‘New Great Game’ for Central Asia, 1759-2004’ examined the expansion of Chinese state power in the ‘Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region’ since the 18th century and the implications of this complex process for China’s foreign policy in Central Asia. -

Mutual Integration Versus Forced Assimilation

Mutual Integration Versus Forced Assimilation: The Conflict between Sandinistas and Miskitu Indians, 1979-1987 by Jordan Taylor Towne An honors thesis submitted to the Honors Committee of The University of Colorado at Boulder Spring 2013 Abstract: This study aims to i) disentangle the white man’s overt tendency of denigrating indigenous agency to ethnic identity and, through the narrative of the Miskitu people of Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast, display that this frequent ethnic categorization oversimplifies a complex cultural identity; ii) bring to the fore the heterogeneity inherent to even the most seemingly unanimous ethnic groups; iii) illustrate the influence of contingent events in shaping the course of history; and iv) demonstrate that without individuals, history would be nonexistent—in other words, individuals matter. Through relaying the story of the Miskitu Indians in their violent resistance against the Revolutionary Sandinistas, I respond contrarily to some of the relevant literature’s widely held assumptions regarding Miskitu homogeneity, aspirations, and identity. This is achieved through chronicling the period leading to war, the conflict itself, and the long return to peace and respectively analyzing the Miskitu reasons for collective resistance, their motives in supporting either side of the fragmented leadership, and their ultimate decision to lay down arms. It argues that ethnic identity played a minimal role in escalating the Miskitu resistance, that the broader movement did not always align ideologically with its representative bodies throughout, and that the Miskitu proved more heterogeneous as a group than typically accredited. Accordingly, specific, and often contingent events provided all the necessary ideological premises for the Miskitu call to arms by threatening their culture and autonomy—the indispensible facets of their willingness to comply with the central government—thus prompting a non-revolutionary grassroots movement which aimed at assuring the ability to join the revolution on their own terms. -

Table S1. the Species Information of Ferula Genus Used in This Study

Table S1. The species information of Ferula genus used in this study. Specimen GenBank Latin name Sample source Sampling parts voucher accession 7-x-z-7-1 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792984 7-x-z-7-2 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792985 7-x-z-7-3 Jeminay County, Xinjiang leaves KF792986 7-x-z-7-4 Jeminay County,Xinjiang leaves KF792987 7-x-z-7-5 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792988 7-x-z-8-2 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792995 Ferula sinkiangensis 7-x-z-7-6 Yining County, Xinjiang roots KF792989 K.M.Shen 7-x-z-7-7 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792990 7-x-z-7-8 Jeminay County, Xinjiang leaves KF792991 7-x-z-7-9 Jeminay County, Xinjiang roots KF792992 7-x-z-7-10 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792993 7-x-z-8-1 Yining County, Xinjiang leaves KF792994 13909 Shawan,County,Xinjiang roots KJ804121 7-x-z-3-2 Fukang County, Xinjiang leaves KF793025 7-x-z-3-5 Fukang County, Xinjiang leaves KF793027 Ferula fukanensis 7-x-z-3-4 Fukang County, Xinjiang leaves KF793026 K.M.Shen 7-x-z-3-1 Fukang County, Xinjiang roots KF793024 13113 Fukang County, Xinjiang roots KJ804103 13114 Fukang County, Xinjiang roots KJ804104 7-x-z-2-4 Toli County, Xinjiang roots KF793002 7-x-z-2-5 Toli County, Xinjiang leaves KF793003 7-x-z-2-6 Fuyun County, Xinjiang leaves KF793004 7-x-z-2-7 Fuyun County, Xinjiang leaves KF793005 7-x-z-2-8 Fuyun County, Xinjiang leaves KF793006 7-x-z-2-9 Toli County, Xinjiang leaves KF793007 Ferula ferulaeoides 7-x-z-2-10 Shihezi City, Xinjiang leaves KF793008 (Steud.) Korov. -

Xinjiang Municipal Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement Project

Ethnic Minority Development Planning Document Ethnic Minority Development Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 39228 December 2007 PRC: Xinjiang Municipal Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement Project Prepared by Kanas Scenic Region Management Commission for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The ethnic minority development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. ADB Financed Project Ethnic Minority Development Plan Kanas Environmental Improvement and Recovery Infrastructure Project of Xinjiang Municipal Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement Project Kanas Scenic Region Management Commission September 2007 Endorsement Letter of the EMDP The Ministry of Finance has approved the Kanas Scenic Region Management Commission (KSRMC) of Altay Prefecture, which is located in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), to implement the Kanas Environmental Improvement and Recovery Infrastructure Project which is financed by the ADB. The project is planned to commence in 2008 and finish in 2012. According to the requirements of ADB, an EMDP for the project should be compiled in accordance with the Social Safeguards Guidelines of the ADB. This EMDP is a key planning document of the project, which is approved and monitored by the ADB. Assisted by the PPTA consultants, the EA and IA have finished this EMDP which contains relevant the procedures of implementation and monitoring, which can guarantee the EMDP to be implemented effectively. The XUAR project management team has empowered KSRMC to be responsible for the implementation of the project and compilation of the EMDP. KSRMC has asked for the views on the draft of this EMDP from relevant bureaus, departments, governments of towns or townships, and communities and absorbed those views into the EMDP. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

“Kashgar City Circle” Industry Development in the Contest of the Silk Road Economic Belt

E3S Web of Conferences 235, 02023 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123502023 NETID 2020 A Study on “Kashgar City Circle” Industry Development in the Contest of the Silk Road Economic Belt Pan Jie1,a, Bai Xiao*2,b(Corresponding Author) 1 Faculty of Transportation and Management, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China 2 Postdoctoral Innovation Practice Base, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China Abstract. Kashgar City Circle is an important node of the new The Silk Road economic belt.Kashgar City Circle will serve as a new economic growth pole in the western region and will promote the rapid development of regional economy.The development of industry is an important driving force for regional economic development.This paper analyzes the four indicators of total output value,output value growth rate,employed population and labor productivity of the 18 industrial sectors of Kashgar City Circle from 2012 to 2016.Combined with the opportunities brought by the Silk Road economic belt background to the development of the Kashgar City Circle industry,this paper puts forward the current policy recommendations for the development of the Kashgar City Circle industry. research on the adjustment and optimization of industrial 1 Introduction structure [6-10],the current economic development situation[11-12],the impact of fixed asset investment on Kashgar is the traffic hub of the ancient The Silk Road, the industrial structure change[13-14].However, based on the traffic hub of the new The Silk Road economic belt, and a background of The Silk Road economic belt, there are major channel for trade with neighboring countries. -

Prevalence and Causes of Blindness, Visual Impairment Among Different

Li et al. BMC Ophthalmology (2018) 18:41 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-018-0705-6 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and causes of blindness, visual impairment among different ethnical minority groups in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, China Yanping Li1, Wenyong Huang2, Aoyun Qiqige3, Hongwei Zhang4, Ling Jin2, Pula Ti5, Jennifer Yip6 and Baixiang Xiao1,2* Abstract Background: The aim of this cross-sectional study is to ascertain the prevalence and causes of blindness, visual impairment, uptake of cataract surgery among different ethnic groups in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Methods: Four thousand one hundred fifty people at 50 years and above from different minority ethnic groups were randomly selected for an eye examination. The four trained eye teams collected data using tumbling E visual chart, torch, portable slit lamp and direct ophthalmoscope in 2015. The World Health Organization’s definition of blindness and visual impairment (VI) was used to classify patients in each ethnic group. Data were analyzed by different minority groups and were compared with Han Chinese. Results: 3977 (95.8%) out of 4150 people were examined. The prevalence of blindness from the study population was 1. 7% (95% confidence interval: 1.3–2.2%).There was no significant difference in prevalence of blindness between Han Chinese and people of Khazak and other minority ethnic groups, nor, between male and female. Cataract was the leading course (65.5%) of blindness and uncorrected refractive error was the most common cause of VI (36.3%) followed by myopic retinopathy. The most common barrier to cataract surgery was lack of awareness of service availability. -

Sayı: 13 Güz 2013

.......... Sayı: 13 Güz 2013 Ankara 1 .......... Dil Araştırmaları/Language Studies Uluslararası Hakemli Dergi ISSN: 1307-7821 Sayı: 13 Güz 2013 Sahibi/Owner Avrasya Yazarlar Birliği adına Yakup DELİÖMEROĞLU Yayın Yönetmeni/Editor Prof. Dr. Ahmet Bican ERCİLASUN Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü/Editorial Director Prof. Dr. Ekrem ARIKOĞLU Yayın Yönetmeni Yardımcısı/Vice Editor Araş. Gör. Hüseyin YILDIZ Yayın Danışma Kurulu/Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Dr. Şükrü Halûk AKALIN • Prof. Dr. Mustafa ARGUNŞAH • Prof. Dr. Sema BARUTÇU ÖZÖNDER • Prof. Dr. Ahmet BURAN • Prof. Dr. İsmet CEMİLOĞLU • Prof. Dr. Hülya KASAPOĞLU ÇENGEL • Prof. Dr. Nurettin DEMİR • Prof. Dr. Hayati DEVELİ • Prof. Dr. Musa DUMAN • Prof. Dr. Tuncer GÜLENSOY • Prof. Dr. Gürer GÜLSEVİN • Prof. Dr. Ayşe İLKER • Prof. Dr. Günay KARAAĞAÇ • Prof. Dr. Leylâ KARAHAN • Prof. Dr. Metin KARAÖRS • Prof. Dr. Yakup KARASOY • Prof. Dr. Ceval KAYA • Prof. Dr. M. Fatih KİRİŞÇİOĞLU • Prof. Dr. Zeynep KORKMAZ • Prof. Dr. Mehmet ÖLMEZ • Prof. Dr. Mustafa ÖNER • Prof. Dr. Mustafa ÖZKAN • Prof. Dr. Nevzat ÖZKAN • Prof. Dr. Çetin PEKACAR • Prof. Dr. Osman Fikri SERTKAYA • Prof. Dr. Vahit TÜRK • Prof. Dr. Cengiz ALYILMAZ • Prof. Dr. Bilgehan Atsız GÖKDAĞ • Doç. Dr. İsmail DOĞAN • Prof. Dr. Zühal YÜKSEL • Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ferhat TAMİR Yazı Kurulu/Executive Board Doç. Dr. Dilek ERGÖNENÇ AKBABA • Yrd. Doç. Dr. Gülcan ÇOLAK BOSTANCI • Doç. Dr. Figen GÜNER DİLEK • Doç. Dr. Feyzi ERSOY • Doç. Dr. Habibe YAZICI ERSOY • Doç. Dr. Yavuz KARTALLIOĞLU • Yrd. Doç. Dr. Veli Savaş YELOK • Dr. Hakan AKÇA • Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hüseyin YILDIRIM Akademik Temsilciler/Academic Representatives Abdulkadir ÖZTÜRK (Kayseri), Yusuf ÖZÇOBAN (Balıkesir), İsmail SÖKMEN (İzmir), Musa SALAN (Çankırı), Aslıhan DİNÇER (İzmir), M. Emin YILDIZLI (Nevşehir), İlker TOSUN (Edirne), Özer ŞENÖDEYİCİ (Trabzon) Düzelti/Redaction Hüseyin YILDIZ İngilizce Danışmanı/English Language Consultant Yrd. -

U:\Docs\Ar16 Xinjiang Final.Txt Deidre 2

1 IV. Xinjiang Security Measures and Conflict During the Commission’s 2016 reporting year, central and re- gional authorities continued to implement repressive security measures targeting Uyghur communities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). In October 2015, Yu Zhengsheng, a member of the Standing Committee of the Communist Party Cen- tral Committee Political Bureau, said authorities should focus on counterterrorism in order to achieve stability in the XUAR.1 Re- ports from international media and rights advocates documented arbitrary detentions,2 oppressive security checkpoints 3 and pa- trols,4 the forcible return of Uyghurs to the XUAR from other prov- inces as part of heightened security measures,5 and forced labor as a means to ‘‘ensure stability.’’ 6 Meng Jianzhu, head of the Party Central Committee Political and Legal Affairs Commission, repeat- edly stressed the need for authorities to ‘‘eradicate extremism,’’ in particular ‘‘religious extremism,’’ in the XUAR in conjunction with security measures.7 The U.S. Government and international ob- servers have asserted that XUAR officials have justified restric- tions on Uyghurs’ religious freedom by equating them with efforts to combat extremism.8 The Commission observed fewer reports of violent incidents in- volving ethnic or political tensions in the XUAR in the 2016 report- ing year than in previous reporting years,9 though it was unclear whether less violence occurred, or Chinese authorities prevented public disclosure of the information. International media and rights